Fltunnwript the LITERARY MAGAZINE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mathmatters and STEAM Expo

Winter 2016-2017 NEWSLETTER MathMatters and STEAM Expo On Saturday, March 18th, Coral Academy of Science Las Vegas will host the 13th annual math contest, MathMatters and our annual STEAM Expo. Executive Director Letter This marks the first year both events will happen concurrently. Central Office Note Our long-established K-12 STEAM Expo is going to be held at Sandy Ridge Sandy Ridge Principal’s Park, Henderson. Students from all five branches of Coral Academy of Note Science, Las Vegas will come together to make this amazing event more Upcoming Events fascinating. Additionally this year there will be art booths as well. This 2017-2018 Calendar free event will help raise funds for many clubs and groups as well as ex- pose our community to all that our students have to offer. Nellis AFB Principal’s Note MathMatters will be held at the Sandy Ridge Campus. The event is free Centennial Hills and open to all 4th and 5th grade students throughout the Las Vegas Val- Principal’s Note ley but pre-registration is required. Students will test their skills by solv- ing 15 challenging math questions ranging from fractions to operations Windmill Principal’s and algebraic thinking. All attendees will enjoy the science demonstra- Note tion on defying gravity by Mad Science of Las Vegas. Tamarus Principal’s Note Winners of the competition will win prizes including: 1st place prize: IPAD Mini2 Accolades 2nd place prize: Kindle Fire HD 8 Student Highlights 3rd place prize: Kindle Fire MathMatters registration information will be coming soon. Reminders We are now accepting online applications for the 2017-2018 school year. -

Felix Issue 0985, 1994

loo<tF The Student Newspaper of Imperiaiperiall ColleqCollegee I 3DRI8B3iaCE||olrj g 210CT94 TCCB-tSCTIONj enamings benefits of the proposal had not. ANDREW DORMAN-SMITH been adequately debated. Professor Shaw said the name of Senior academics at. the. the Department itself does not Department, of Mineral Resources overly matter, and said he was, Engineering (MRE) have called "a believer in tradition". Professor for further discussions over a plan Shaw would not say if he sup- to rename the department. Earth ported the name change proposal. Resources Engineering has However, the new head of emerged as the favourite choice MRE, and Dean of the newly for a new name, after discussions established Graduate School of between college officials. the Environment, Professor The change has been mooted Woods, is believed to think the following a letter from the proposal is a 'great idea'. His role Professor John Archer, Pro- as Dean will be to coordinate the Rector, which asks for comments departments of Imperial, and to on the new title. Professor Archer, present the benefits for research said that he has received only one of the college in line with a review negative response to his letter, completed in May by Sir John and claimed that most of the Mason. department's staff agree with the The other two RSM depart- proposal. But Professor Archer ments may also change names. said discussions are continuing - The college's chief decision mak- despite the publication of an offi- ing body, the Management cial college note which says the Finnish Embassy Planning Group (MPG), has sug- Photo by Ivan Chan change will take place "shortly". -

Beverly Hills

briefs • City to subsidize $1.6 million briefs • City refuses to declare rudy cole • My recommendations loan for City Manager housing Page 3 opinion on subway route Page 4 for state office Page 6 ALSO ON THE WEB Beverly Hills www.bhweekly.com WeeklySERVING BEVERLY HILLS • BEVERLYWOOD • LOS ANGELES Issue 575 • October 7 - October 13, 2010 OUR 11th Beverly Hills’ Anniversary First Lady The Weekly’s interview with Lonnie Delshad cover story • pages 8-9 Few motorists would risk their lives by for anyone but a Democrat because it would briefs • Lively subway route hearing at briefs • Julian Gold announces rudy cole • Roxbury Park Page 2 candidacy for City Council Page 3 United city speaks Page 6 bicycle community in the region, and isn’t have disappointed his liberal mother. As ALSO ON THE WEB Beverly Hills www.bhweekly.com that part of our transportation problem? Too one of my favorite commentators, Dennis letters too few folks using alternate transportation Prager, pointed out in a recent article, so WeeklySERVING BEVERLY HILLS • BEVERLYWOOD • LOS ANGELES means too many cars on the road. Bike- many registered Democrats vote for Left- Issue 574 • September 30 - October 6, 2010 friendly infrastructure not only protects wing candidates who do not share their Beverly High Athletic cyclists entitled to ride all of the streets in views for purely emotional, nonsensical Alumni to be inducted & email our city, but it reduces motorist liability too. reasons. In Rudy’s case, it is because his Simply put, bikes belong, so let’s plan for mother would disapprove of him voting into Hall of Fame them to accommodate bikes safely. -

Visualizing Levinas:Existence and Existents Through Mulholland Drive

VISUALIZING LEVINAS: EXISTENCE AND EXISTENTS THROUGH MULHOLLAND DRIVE, MEMENTO, AND VANILLA SKY Holly Lynn Baumgartner A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2005 Committee: Ellen Berry, Advisor Kris Blair Don Callen Edward Danziger Graduate Faculty Representative Erin Labbie ii © 2005 Holly Lynn Baumgartner All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Ellen Berry, Advisor This dissertation engages in an intentional analysis of philosopher Emmanuel Levinas’s book Existence and Existents through the reading of three films: Memento (2001), Vanilla Sky (2001), and Mulholland Drive, (2001). The “modes” and other events of being that Levinas associates with the process of consciousness in Existence and Existents, such as fatigue, light, hypostasis, position, sleep, and time, are examined here. Additionally, the most contested spaces in the films, described as a “Waking Dream,” is set into play with Levinas’s work/ The magnification of certain points of entry into Levinas’s philosophy opened up new pathways for thinking about method itself. Philosophically, this dissertation considers the question of how we become subjects, existents who have taken up Existence, and how that process might be revealed in film/ Additionally, the importance of Existence and Existents both on its own merit and to Levinas’s body of work as a whole, especially to his ethical project is underscored. A second set of entry points are explored in the conclusion of this dissertation, in particular how film functions in relation to philosophy, specifically that of Levinas. What kind of critical stance toward film would be an ethical one? Does the very materiality of film, its fracturing of narrative, time, and space, provide an embodied formulation of some of the basic tenets of Levinas’s thinking? Does it create its own philosophy through its format? And finally, analyzing the results of the project yielded far more complicated and unsettling questions than they answered. -

The Italian Girl in Algiers

Opera Box Teacher’s Guide table of contents Welcome Letter . .1 Lesson Plan Unit Overview and Academic Standards . .2 Opera Box Content Checklist . .8 Reference/Tracking Guide . .9 Lesson Plans . .11 Synopsis and Musical Excerpts . .32 Flow Charts . .38 Gioachino Rossini – a biography .............................45 Catalogue of Rossini’s Operas . .47 2 0 0 7 – 2 0 0 8 S E A S O N Background Notes . .50 World Events in 1813 ....................................55 History of Opera ........................................56 History of Minnesota Opera, Repertoire . .67 GIUSEPPE VERDI SEPTEMBER 22 – 30, 2007 The Standard Repertory ...................................71 Elements of Opera .......................................72 Glossary of Opera Terms ..................................76 GIOACHINO ROSSINI Glossary of Musical Terms .................................82 NOVEMBER 10 – 18, 2007 Bibliography, Discography, Videography . .85 Word Search, Crossword Puzzle . .88 Evaluation . .91 Acknowledgements . .92 CHARLES GOUNOD JANUARY 26 –FEBRUARY 2, 2008 REINHARD KEISER MARCH 1 – 9, 2008 mnopera.org ANTONÍN DVOˇRÁK APRIL 12 – 20, 2008 FOR SEASON TICKETS, CALL 612.333.6669 The Italian Girl in Algiers Opera Box Lesson Plan Title Page with Related Academic Standards lesson title minnesota academic national standards standards: arts k–12 for music education 1 – Rossini – “I was born for opera buffa.” Music 9.1.1.3.1 8, 9 Music 9.1.1.3.2 Theater 9.1.1.4.2 Music 9.4.1.3.1 Music 9.4.1.3.2 Theater 9.4.1.4.1 Theater 9.4.1.4.2 2 – Rossini Opera Terms Music -

Collaborating with James Baldwin on a Screenplay of Giovanni's Room

DISPATCH “We can love one another in other ways”: Collaborating with James Baldwin on a Screenplay of Giovanni’s Room Michael Raeburn Abstract The author discusses his personal relationship with James Baldwin, recounting their collaboration on a film script for an adaptation of Giovanni’s Room. Keywords: Giovanni’s Room, Michael Raeburn, James Baldwin, film, Paris, Marlon Brando, Robert de Niro, Saint-Paul de Vence, Steve McQueen It was a bright summer’s afternoon in the south of France on 2 August 1977. In the garden of his house below the ramparts of the village of Saint-Paul de Vence, James Baldwin was celebrating his 53rd birthday. He made a brief speech thanking his friends for coming. Then, much to my surprise, he announced that he and I had embarked on “an adventure” to write a screenplay of Giovanni’s Room (1956). He raised his glass to me; most of the guests raised theirs to us in hesitant celebration. The idea had occurred a few weeks before. It came from Jimmy; I cannot call him James, as to me, and to all his friends, he was Jimmy. His offer to collaborate on the adaptation had come out of the blue. Only a set of mutually shared circum- stances going back to our first meeting can explain his proposal which was pre- sented to me in these words: “We can also love one another in other ways: we’ll write the script of ‘Giovanni’s Room’ together.” To most outsiders we were the most improbable match: a young, novice film- maker from colonial Africa, and a world-famous African-American writer from Harlem. -

General Awareness–Current Affairs Month of March-2019

GENERAL AWARENESS–CURRENT AFFAIRS MONTH OF MARCH-2019 List of Important Days March 1 - Zero Discrimination Day (Theme – “Act to change laws that Discriminate”) March 4 - National Safety Day (Themes – “Cultivate and Sustain A Safety Culture for Building Nation”) Mar 4-10 - National Safety Week March 7 - Janaushadhi Diwas March 8 - International Women’s Day (Theme – “Think Equal, Build Smart, Innovate for Change”). March 12 - World Day against Cyber Censorship March 12 - 30th anniversary of the World Wide Web (WWW) March 14 - (2nd Thursday of March) World Kidney Day (Theme - “Kidney Health for Everyone Everywhere”) March 14 - Pi Day (Pi's value (3.14)) March 15 - World Consumer Rights Day (In India this day is celebrated as Viswa Upabhokta Adhikar Diwas). (Theme – “Trusted Smart Products”) March 20 - International Day of Happiness. (Theme – “Happier Together”) March 20 - World Day of Theatre for Children and Young People March 20 - World Sparrow Day. (Theme – “I LOVE Sparrows”) March 21 - International Day of Forests. (Theme “Forests and Education”) March 21 - World Poetry Day March 21 - World Down Syndrome Day March 21 - International Day for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (Theme – “Mitigating and countering rising nationalist populism and extreme supremacist ideologies”) March 21 - World Puppetry Day March 22 - World Water Day (Theme – “Leaving no one behind”) March 23 - World Meteorological Day (Theme – “The Sun, the Earth and the Weather”) March 23 - 88th Shaheed Diwas (Martyr’s Day) March 24 - World Tuberculosis (TB) Day (Theme – “It’s time”) March 25 - International Day of Remembrance of the Victims of Slavery and Transatlantic Slave Trade. (Theme – “Remember Slavery: The Power of the Arts for Justice”) March 26 - Independence Day of Bangladesh March 27 - World Theatre Day (WTD) March 30 - Rajasthan Diwas Reserve Bank of India • The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has fined Yes Bank ₹1 crore for not complying with its directions about SWIFT, a financial messaging software. -

Towncrier-Dec2018.Pdf

2 December 13, 2018 THE TOWN CRIER Cover Story Paul Revere Middle School ’Tis the Season of Giving Patriots are giving back to their community by lending out helping hands to those in need. start of Revere’s season of giv- By ALEXA DREYFUS es that Patriots were able to win Positive Chalk on Nov 30. This and JULIA MUSUMECI ing back. were gift cards, and the winners was a great opportunity for Pa- The next week was Hallow- were Johnny Harvey and Dan- triots to write positive messag- As the weather gets colder, een, which everyone knows is ielle Efron. es, outside of the X building, to Revere gets warmer. Patriots filled with tons of candy. Af- Right after Halloween, the refugees who do not get a good lend helping hands all around ter Halloween, there is always Community Service Club col- education. To host the event, the campus, and spread the holiday leftover candy that gets thrown lected old crayons, that were not Community Service Club had cheer. There were many oppor- away. So, the Community Ser- being used anymore. The cray- snack sales from Nov 5 to Nov tunities for Patriots to partici- vice Club organized Operation ons were donated to a school 9 and the proceeds went to Cis- pate in helping others, led by the Gratitude where they collected that could not afford to supply arva Refugee Learning Center, Community Service Club, Lead- all of that extra candy that would their classrooms with the same which helps out refugees in Syr- ership and even on their own. -

DARK CITY HIGH the High School Noir of Brick and Veronica Mars Jason A

DARK CITY HIGH THE HIGH SCHOOL NOIR OF BRICK AND VERONICA MARS Jason A. Ney ackstabbing, adultery, blackmail, robbery, corruption, and murder—you’ll find them all here, in a place where no vice is in short supply. You want drugs? Done. Dames? They’re a dime a dozen. But stay on your toes because they’ll take you for all you’re worth. Everyone is work- ing an angle, looking out for number one. Your friend could become your enemy, and if the circumstances are right, your enemy could just as easily become your friend. Alliances are as unpredictable and shifty as a career criminal’s moral compass. Is all this the world of 1940’s and 50’s film noir? Absolutely. But, tures like the Glenn Ford vehicle The Blackboard Jungle (1955) and Bas two recent works—the television show Veronica Mars (2004- melodramas like James Dean’s first feature,Rebel Without a Cause 2007) and the filmBrick (2005)—convincingly argue, it is also the (1955). But a noir film from the years of the typically accepted noir world of the contemporary American high school. cycle (1940-1958) populated primarily by teenagers and set inside a That film noir didn’t extend its seductive, deadly reach into the high school simply does not exist. Perhaps noir didn’t make it all the high schools of the forties and fifties is somewhat surprising, given way into the halls of adolescent learning because adults still wanted how much filmmakers danced around the edges of what we now to believe that the teens of their time retained an element of their call noir when crafting darker stories about teens gone bad. -

Special History Study, Jimmy Carter National Historic Site and Preservation District, 29

special history study november 1991 by William Patrick O'Brien JIMMY CARTER NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE AND PRESERVATION DISTRICT • GEORGIA UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR / NATIONAL PARK SERVICE TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS v PREFACE vii INTRODUCTION 1 VISION STATEMENT 2 MAP - PLAINS AND VICINITY 3 PART ONE: BACKGROUND AND HISTORY BACKGROUND AND HISTORY 7 SOUTHWEST GEORGIA - REGION AND PLACE 9 SOUTHWEST GEORGIA - PEOPLE (PRE-HISTORY TO 1827) 11 SOUTHWEST GEORGIA, SUMTER COUNTY AND THE PLAINS OF DURA (1827-1865) 14 FROM THE PLAINS OF DURA TO JUST PLAIN "PLAINS" (1865-1900) 21 THE ARRIVAL AND PROGRESS OF THE CARTERS (1900-1920) 25 THE WORLD OF THE CARTERS AND JIMMY'S CHILDHOOD (1920-1941) 27 THE WORLD OUTSIDE OF PLAINS (1941-1953) 44 THE END OF THE OLD ORDER AND THE BEGINNING OF THE NEW: RETURN TO PLAINS (1953-1962) 46 ENTRY INTO POLITICS (1962-1966) 50 CARTER, PLAINS AND GEORGIA: YEARS OF CHANGE AND GROWTH - THE RISE OF THE NEW SOUTH (1966-1974) 51 PRESIDENTIAL VICTORY, PRESIDENTIAL DEFEAT (1974-1980) 55 THE CHRISTIAN PHOENIX AND THE "GLOBAL VILLAGE" - CARTER AND PLAINS (1980-1990) 58 CONCLUSION 63 PART TWO: INVENTORY AND. ASSESSMENT OF CULTURAL RESOURCES - JIMMY CARTER NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE AND PRESERVATION DISTRICT INTRODUCTION 69 EXTANT SURVEY ELEMENTS - JIMMY CARTER NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE AND PRESERVATION DISTRICT 71 I. Prehistory to 1827 71 II. 1827-1865 72 III. 1865-1900 74 IV. 1900-1920 78 V. 1920-1941 94 VI. 1941-1953 100 iii VII. 1953-1962 102 VIII. 1962-1966 106 IX. 1966-1974 106 X. 1974-1980 108 XI. 1980-1990 109 RECOMMENDATIONS FOR ADDITIONAL SURVEY ELEMENTS PLAINS, GEORGIA . -

Irishecholabor100magazine

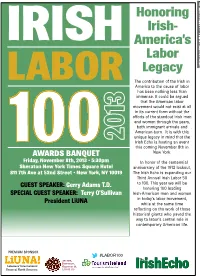

Page 17 Honoring / Irish Echo / NOVEMBER 6 - 12, 2013 / www.irishecho.com Irish- IRISH America’s Labor Legacy LABOR The contribution of the Irish in America to the cause of labor has been nothing less than immense. It could be argued that the American labor 3 movement would not exist at all 1 in its current form without the efforts of the standout Irish men and women through the years, 0 both immigrant arrivals and American-born. It is with this unique legacy in mind that the 2 Irish Echo is hosting an event this coming November 8th in AWARDS BANQUET New York. Friday, November 8th, 2013 • 5:30pm In honor of the centennial Sheraton New York Times Square Hotel anniversary of the 1913 lockout, 811 7th Ave at 52nd Street • New York, NY 10019 The Irish Echo is expanding our Third Annual Irish Labor 50 GUEST SPEAKER: Gerry Adams T.D. to 100. This year we will be honoring 100 leading SPECIAL GUEST SPEAKER: Terry O’Sullivan Irish-American men and women in today’s labor movement, President LiUNA while at the same time reflecting on the work of those historical giants who paved the way to labor’s central role in contemporary American life. PREMIUM SPONSOR #LABOR100 The ARCHER, BYINGTON, Laborers’ International GLENNON & IrishEcho Union of North America LEVINE LLP Page Page 18 IRISH LABOR 100 The Irish gave life to American labor By Terry O'Sullivan and leading various labor organizations. [email protected] For many of these warriors of the working class, their work is more than a n this centennial year of the historic job, and larger than a career; it is a Dublin Lockout, it is fitting that we lifetime's commitment. -

THE POINT WHERE THEY MEET and OTHER STORIES a Thesis

THE POINT WHERE THEY MEET AND OTHER STORIES A thesis submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts by Brittany Stone May 2011 Thesis written by Brittany Stone M.F.A., Kent State University, 2011 B.A., Hiram College, 2008 Approved by _____________Robert Pope______________, Advisor, MA Thesis Defense Committee ___________Varley O’Connor____________, Members, MA Thesis Defense Committee _____________Robert Miltner____________, Members, MA Thesis Defense Committee Approved by ____________Ron Corthell_______________, Chair, Department of English ___________John R.D. Stalvey____________, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS…………………………………………………………....vi A REAL HOLLYWOOD PRODUCTION…………………………………………….1 THE SPIDER………………………………………………………………………….23 THE POINT WHERE THEY MEET…………………………………………………46 BOBCAT……………………………………………………………………………...65 OF DESPERATION AND CARS…………………………………………………….75 THE HEN……………………………………………………………………………...92 AS GOOD AS MOTHER…………………………………………………………….111 THE HOUR BEFORE DEATH………………………………………………………128 SAILING MAN……………………………………………………………………….144 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This work is dedicated to my grandparents, Gene and Garcia Burchett of Duck, West Virginia. They’ve shown me that beauty, love, and joy can thrive in adversity. Little bits of their spirits are in each of these stories. Brittany Stone 3/15/11, Kent, OH iv A REAL HOLLYWOOD PRODUCTION The man came on a Saturday morning and knocked on Bud’s door. The man didn’t know Bud and Bud didn’t know him. Bud had been sitting in the kitchen in his big old house, writing a check for the gas. For as long as he’d had been paying his own way—too many years, as far as he was concerned—bills came first on Saturday mornings. He tucked the pen behind his ear and answered the door.