HALL- If Walls Could Talk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

8. E-Book BARA LAPAR JADIKAN PALU TARING

BARA LAPAR JADIKAN PALU COLOPHON TARING PADI Bara Lapar Jadikan Palu Editor I Gede Arya Sucitra Nadiyah Tunnikmah Penulis Bambang Witjaksono Mohamad Yusuf Aminudin TH Siregar Risa Tokunaga Desain & Tata Letak Kadek Primayudi Semua gambar dan foto diambil dari koleksi Taring Padi. Hak Cipta @ 2018 Galeri R.J. Katamsi ISI Yogyakarta Hak Cipta dilindungi oleh undang-undang. Dilarang memperbanyak atau memindahkan sebagian atau seluruh isi buku ini dalam bentuk apapun, baik secara elektronis maupun mekanis, termasuk memfotocopy, merekam atau dengan sistem penyimpanan lainnya, tanpa ijin tertulis dari penerbit. Penerbit: Galeri R.J. Katamsi, ISI Yogyakarta Jalan Parangtritis km 6,5 Sewon Bantul Yogyakarta www.isi.ac.id Cetakan Pertama, November 2018 Perpustakaan Nasional: Katalog Dalam Terbitan I Gede Arya Sucitra & Nadiyah Tunnikmah TARING PADI Bara Lapar Jadikan Palu Yogyakarta: Galeri R.J. Katamsi ISI Yogyakarta, 2018 128 hlm.; 15 cm x 21 cm ISBN: 978 - 602 - 53474 - 0 - 5 KPRP_Yustoni, Mereka yang Tanggung Jawab, Cat Genteng di atas Kain, 220 x 300 cm, 1998 4 7 Pengantar Kepala Galeri R.J. Katamsi ISI Yogyakarta 10 Pengantar Rektor ISI Yogyakarta 15 Bara Lapar Jadikan Palu, 20 Tahun Taring Padi Bambang Witjaksono 37 Taring Padi Berada Mohamad Yusuf 68 Deklarasi Taring Padi 71 Taring Padi Dalam Sejarah Seni Aminudin Th Siregar 87 The 20 Years of Taring Padi: Spirit of Solidarity and Political Imagination Crossing Borders Risa Tokunaga 106 Biodata Taring Padi 124 Tentang Penulis 126 Tim Kerja 128 Terima Kasih 5 Foto bersama di Gampingan, 2010 6 KPRP _Yustoni, Sedumuk Bhatuk, Cat Genteng di atas Kain, 220 x 300 cm, 1998 (Detail) 7 PENGANTAR Salam budaya, Puji syukur kita panjatkan kehadapan Tuhan Yang Maha Esa pun Maha Karya atas dianugerahkannya kesehatan dan kreativitas seni berlimpah pada kita semua. -

Counter-Hegemony of the East Java Biennale Art Community Against the Domination of Hoax Content Reproduction Perlawanan Hegemoni

Counter-hegemony of the East Java Biennale art community against the domination of hoax content reproduction Perlawanan hegemoni komunitas seni Biennale Jawa Timur terhadap dominasi reproduksi konten hoax Jokhanan Kristiyono1*, Rachmah Ida2, & Musta’in Mashud3 1Doctoral Program of Social Sciences, Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, Universitas Airlangga 2Department of Communication, Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, Universitas Airlangga 3Department of Sociology, Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, Universitas Airlangga Address: Jalan Dharmawangsa Dalam, Airlangga, Surabaya, East Java 60286 E-mail: [email protected] Abstract This research analyses and describes in detail how the digital biennale activities that are a part of the Indonesian Digital arts community has become a form of criticism and silent resistance to the social hegemony. It refers to the ideology, norms, rules, and myths that exist in modern society in Indonesia, especially the reproduction of hoax content. Hoax refers to the logic people who live in a world of cyber media with all of its social implications. This phenomenon is a problem, and it is at the heart of the exploration of the art community in East Java Biennale. The critical social theory perspective of Gramsci’s theory forms the basis of this research analysis. The qualitative research approach used a digital ethnomethodology research method focused on the online and offline social movements in the Biennale Art Community. The data collection techniques used were observation and non-active participation in the process of reproduction-related to the exhibition of Indonesian Biennale digital artworks. It was then analyzed using Gramsci’s hegemony theory. -

Sudandyo Widyo Aprilianto

Sudandyo Widyo Aprilianto Date of Birth: April 19, 1980 Address: WR Supratman 35, Kauman Juwana Pati, Central Java 59185 Indonesia Telephone: +6285878961235 E-mail: [email protected] Education 1999-2005: Student of Fine Art and Sculpture at the Institute of Art Indonesia, Yogyakarta. 2007: Three-month English intensive at Lewis Adult School, Santa Rosa, CA U.S.A. 2007: Three-month English class at Santa Rosa Junior College, Santa Rosa, CA U.S.A. Experience October, 1999: Joined with group collective of artists, Sanggar Caping, Yogyakarta. December, 1999: First exhibition and performance with Sanggar Caping, at Gampingan Art Community, Yogyakarta. April, 2001: Earth Day street performance using body painting and expressive movement, with Sanggar Caping, at Malioboro Street, Yogyakarta. May, 2001: Joined with group collective of artists, Taring Padi, Yogyakarta. May, 2003: Workshop of drawing and painting with Ngijo village children, in Ngijo, Yogyakarta. September, 2003: Performance for the opening exhibition of Dialog Dua Kota (Dialogue of Two Cities) in Semarang. March, 2004: Workshop of puppet and banner-making, with Taring Padi, Yogyakarta. April, 2004: Performance and costume party, Earth Day Festival,Yogyakarta. September, 2005: Created an installation, Urban Culture, with Taring Padi, in CP Biennial, Jakarta. December, 2005, Facilitator of art and music workshops, Forest Art Festival, Blora, Central Java. March, 2006: Duo Exhibition of drawing and monoprint, Selamat Datang Hari Minggu (Welcome Sunday), Yogyakarta. April, 2006: Experimental performance, Terror and Reconciliation, with Taring Padi, Yogyakarta. May-August, 2006: Organizer and facilitator, taught and created art workshops with children who were victims of the earthquake in Yogyakarta with Taring Padi. -

Seni Jalanan Yogyakarta

PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI SENI JALANAN YOGYAKARTA TESIS Di ajukan kepada Program Magister Ilmu Religi dan Budaya Untuk memenuhi sebagian Persyaratan guna Memperoleh gelar Magister Humaniora (M.Hum) Dalam bidang Ilmu Religi dan Budaya Konsentrasi Budaya Pembimbing: Dr Alb. Budi Susanto SJ. Drs M. Dwi Marianto MFA. PhD. Oleh Syamsul Barry NIM: 036322008 MAGISTER ILMU RELIGI DAN BUDAYA UNIVERSITAS SANATA DHARMA YOGYAKARTA 2008 PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PERNYATAAN Dengan ini saya menyatakan bahwa dalam tesis ini tidak terdapat karya yang pernah diajukan untuk memperoleh kesarjanaan di suatu perguruan tinggi dan sepanjang sepengetahuan saya juga tidak terdapat karya atau pendapat yang pernah ditulis atau diterbitkan orang lain, kecuali yang secara tertulis diacu dalam tesis ini dan disebutkan dalam daftar pustaka. Yogyakarta, 7 Januari 2008 Syamsul Barry PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI LEMBAR PERNYATAAN PERSETUJUAN PUBLIKASI KARYA ILMIAH UNTUK KEPENTINGAN AKADEMIS Yang bertanda tangan di bawah ini, saya mahasiswa Universitas Sanata Dharma: Nama : Syamsul Barry Nomor Mahasiswa : 036322008 Demi pengembangan ilmu pengetahuan, saya memberikan kepada Perpustakaan Universitas Sanata. Dharma karya ilmiah saya yang berjudul: SENI JALANAN YOGYAKARTA beserta perangkat yang diperlukan (bila ada). Dengan demikian saya memberikan kepada Perpustakaan Universitas Sanata Dharma hak untuk menyimpan, me- ngalihkan dalam bentuk media lain, -

Socio-Political Criticism in Contemporary Indonesian Art

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Spring 2019 Socio-Political Criticism in Contemporary Indonesian Art Isabel Betsill SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Art and Design Commons, Art Practice Commons, Asian Studies Commons, Contemporary Art Commons, Graphic Communications Commons, Pacific Islands Languages and Societies Commons, Politics and Social Change Commons, Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons, Social Influence and Political Communication Commons, and the Sociology of Culture Commons Recommended Citation Betsill, Isabel, "Socio-Political Criticism in Contemporary Indonesian Art" (2019). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 3167. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/3167 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SOCIO-POLITICAL CRITICISM IN CONTEMPORARY INDONESIAN ART Isabel Betsill Project Advisor: Dr. Sartini, UGM Sit Study Abroad Indonesia: Arts, Religion and Social Change Spring 2019 1 CONTEMPORARY INDONESIAN ART ABOUT THE COVER ART Agung Kurniawan. Very, Very Happy Victims. Painting, 1996 Image from the collection of National Heritage Board, Singapore Agung Kurniawan is a contemporary artist who has worked with everything from drawing and comics, to sculpture to performance art. Most critics would classify Kurniawan as an artist-activist as his art pieces frequently engages with issues such as political corruption and violence. The piece Very, Very happy victims is about how people in a fascist state are victims, but do not necessarily realize it because they are also happy. -

Contemporary Art from Indonesia Termasuk Contemporary Art from Indonesia

Contemporary art from Indonesia Termasuk Contemporary art from Indonesia preposition including termasuk, dan ... juga adjective included termasuk, terhitung inclusive inklusif, termasuk belonging termasuk verb belong termasuk, tergolong, kepunyaan be included termasuk, dicantumkan, masuk appertain berhubungan, tergolong, termasuk Presented by Indo Art Link and John Cruthers in association with Darren Knight Gallery, 19 January – 16 February 2019. Darren Knight Gallery, Sydney 840 Elizabeth Street, Waterloo NSW 2017 Australia Foreword Aaron Seeto Director, Museum MACAN, Jakarta As I gather my thoughts to write this foreword, my news feed is filled with images of the most recent natural disaster in Indonesia. The volcano Anak Krakatau, or ‘child of Krakatau’, has partly collapsed and a tsunami follows – with few warnings and a sharply rising death toll. Persisting mental images of natural disasters, along with natural resources and terrorism, may be the limits of the Australian imagination of Indonesia. With a population of over 265 million people and a rich ethnic and religious diversity mixed with a complex colonial and national history, for Australia there is much more to understand. The same may be said for the art world. Beyond small pockets of interest within museum collections, cohorts of curators and art historians, and specialised collectors, the impact of Australia’s geographic proximity on the quality of our cultural understanding of our nearest neighbour is limited. In the late 1990s and 2000s, there was a wave of interest coinciding with the participation of several important artists in exhibitions in Australia, South East Asia and elsewhere – names like Heri Dono, Dadang Christanto, Arahmaiani, Tisna Sanjaya and FX Harsono, who should be better known here, not only because of their participation in 2 3 exhibitions like the Asia Pacific Triennial, or for some, in projects such as the Artist Regional Exchange in the 1980-1990s, but because their work is fundamental to an understanding of Indonesian art, at a particular social and political moment. -

A Strong Passion For

art in design A Strong Passion With a life mission of bringing Indonesian literature worldwide, John McGlynn, founder of the Lontar Foundation, also shares a deep passion for Art for Indonesian modern and contemporary art. PHOTOS BY Bagus Tri Laksono rt collecting is not just a hobby, it is very personal and a profound dedication. It can be about the money, but it is Deborah rarely an issue. Like any aspiration, it requires a burning Iskandar passion and years of diving into the vast and dynamic A Art Consultant sea of art. — For John H. McGlynn, his love for art started early on. After Deborah Iskandar pursuing fine arts and theatre at the University of Wisconsin in qualifies as an expert the United States, McGlynn came to Indonesia in 1976 to study on Indonesian and the art of traditional wayang puppetry. But after learning and international art, becoming fluent in the Indonesian language, McGlynn decided to with over 20 years of experience in pursue a different career path. This stemmed his life-long affair Southeast Asia, with Indonesian literature as he became one of the most notable heading both translators of Indonesian literature and a prodigious supporter of Sotheby’s and the local arts scene. Christie’s Indonesia during her career before establishing In 1987, McGlynn founded the Lontar Foundation along with ISA Art Advisory in prominent authors, Goenawan Mohamad, Sapardi Djoko Damono, 2013. Her company and Umar Kayam. He has since committed most of his time now branded ISA Art helping the growth of Indonesia’s literary significance to an and Design, provides international audience. -

Katalog Hutan Di Titik Nol.Cdr

Art Exhibition “Hutan di Titik Nol” Katalog ini dibuat sebagai suplemen pada acara Climate Art Festival pada pameran seni berjudul: “Hutan di Titik Nol” Arahmaiani|Arya Pandjalu|Dwi Setianto|Setu Legi|Katia Engel Taring Padi|Sara Nuytemans|Natalie Driemeyer & Anna Peschke Pengarah Artistik Bram Satya 2-12 Oktober 2013 Sangkring Art Space Nitiprayan RT 01 RW 20 No. 88, Ngestiharjo, Kasihan, Bantul, Yogyakarta Penulis Ade Tanesia Christina Schott Desain Wimbo Praharso Penerbit Jogja Interkultur © 2013 This Catalogue is published to accompany Climate Art Festival Event Art Exhibition: “GROUND ZERO FOREST” Arahmaiani|Arya Pandjalu|Dwi Setianto|Setu Legi|Katia Engel Taring Padi|Sara Nuytemans|Natalie Driemeyer & Anna Peschke Artistic Director Bram Satya Oct 2nd - 12th, 2013 Sangkring Art Space Nitiprayan RT 01 RW 20 No. 88 Ngestiharjo, Kasihan, Bantul, Yogyakarta. Writer Ade Tanesia Christina Schott Art Exhibition Design Wimbo Praharso “Hutan di Titik Nol” Publisher Jogja Interkultur © 2013 Cover: Katia Engel “Hujan Abu / Grey Rain“ Katalog ini dibuat sebagai suplemen pada acara Climate Art Festival pada pameran seni berjudul: “Hutan di Titik Nol” Arahmaiani|Arya Pandjalu|Dwi Setianto|Setu Legi|Katia Engel Taring Padi|Sara Nuytemans|Natalie Driemeyer & Anna Peschke Pengarah Artistik Bram Satya 2-12 Oktober 2013 Sangkring Art Space Nitiprayan RT 01 RW 20 No. 88, Ngestiharjo, Kasihan, Bantul, Yogyakarta Penulis Ade Tanesia Christina Schott Desain Wimbo Praharso Penerbit Jogja Interkultur © 2013 This Catalogue is published to accompany Climate Art Festival Event Art Exhibition: “GROUND ZERO FOREST” Arahmaiani|Arya Pandjalu|Dwi Setianto|Setu Legi|Katia Engel Taring Padi|Sara Nuytemans|Natalie Driemeyer & Anna Peschke Artistic Director Bram Satya Oct 2nd - 12th, 2013 Sangkring Art Space Nitiprayan RT 01 RW 20 No. -

Consequential Privileges of the Social Artists: Meandering Through the Practices of Siti Adiyati Subangun, Semsar Siahaan and Moelyono

Consequential Privileges of the Social Artists: Meandering through the Practices of Siti Adiyati Subangun, Semsar Siahaan and Moelyono Grace Samboh Southeast of Now: Directions in Contemporary and Modern Art in Asia, Volume 4, Number 2, October 2020, pp. 205-235 (Article) Published by NUS Press Pte Ltd DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/sen.2020.0010 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/770700 [ Access provided at 24 Sep 2021 23:03 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Consequential Privileges of the Social Artists: Meandering through the Practices of Siti Adiyati Subangun, Semsar Siahaan and Moelyono GRACE SAMBOH Abstract How do artists work with people? How do artists work with many people? What do the people who work with these artists think about the work? Does the fact that they are artists matter to these people? What makes being an artist different from other (social) professions? Is the difference acknowledged? Is the difference fundamental? Does it have to be different? In the effort of locating different forms of artistic practice and planetary responsibilities, this essay addresses these questions through artists’ contexts and works, be it artworks, collective projects, collaborative efforts, living and working choices or writings. We want to open ourselves to the fact that problems in the arts are no longer limited to artists’ [and artistic] issues, but also any problems related to our society, be it in the world of science, technology, society or even the day-to-day. —Siti Adiyati Subangun et al., 19911 Southeast of Now Vol. -

DDB Catalog.Pdf

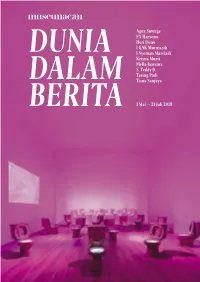

1 Krisna Murti (l. / b. Indonesia, 1957) Makanan Tidak Mengenal Ras (1999/2019) Foodstuffs Are Ethnic, Never Racist (detail) 12 kloset duduk, video digital kanal tunggal dialihkan dari format VHS, proyeksi digital, cetak digital di atas Duratrans, lampu bohlam LED, lampu PAR LED 12 toilets, single channel digital video transferred from VHS, digital projection, digital print on Duratrans, LED light bulb, LED PAR light Durasi video / Video duration 14:54 Dimensi beragam / Variable dimensions Koleksi milik perupa / Collection of the artist 4 5 Heri Dono (l. / b. Indonesia, 1960) Heri Dono (l. / b. Indonesia, 1960) Operasi Pengendalian Pikiran (1999) Operasi Pengendalian Pikiran (1999) Operation Mind Control Operation Mind Control (detail) (detail) Kawat berduri, adaptor, gelas minum, Kawat berduri, adaptor, gelas minum, pelat kawat, kabel, pengatur waktu otomatis pelat kawat, kabel, pengatur waktu otomatis Barbed wire, adaptor, drinking glass, Barbed wire, adaptor, drinking glass, wire plate, cable, automatic timer wire plate, cable, automatic timer ± 104 x 50 x 50 cm ± 104 x 50 x 50 cm Koleksi milik perupa / Collection of the artist Koleksi milik perupa / Collection of the artist 6 7 Diterbitkan untuk pameran Dunia dalam Berita oleh Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Nusantara (Museum MACAN) dan diselenggarakan pada tanggal 1 Mei 2019 sampai 21 Juli 2019 Published for Dunia dalam Berita, an exhibition organized by the Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Nusantara (Museum MACAN) and held on 1 May 2019 to 21 July 2019 Penerbit Publisher The Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Nusantara (Museum MACAN) AKR Tower, Level M Jl. Panjang No. 5 Kebon Jeruk Jakarta Barat 11530, Indonesia Phone. -

Tembok Dan Kritik Lingkungan Membaca Karya Street Art Di Desa Geneng

TEMBOK DAN KRITIK LINGKUNGAN MEMBACA KARYA STREET ART DI DESA GENENG Skripsi Diajukan Oleh ADITYA RAKARENDRA 13321038 PROGRAM STUDI ILMU KOMUNIKASI FAKULTAS PSIKOLOGI DAN ILMU SOSIAL BUDAYA UNIVERSITAS ISLAM INDONESIA YOGYAKARTA 2018 HALAMAN MOTTO Hiduplah seakan-akan kamu akan mati besok, belajarlah seakan-akan kamu akan hidup selamanya -Mahatma Gandhi HALAMAN PERSEMBAHAN Karya ini dipersembangkan untuk: 1. Mama, Papa dan Kakak Adik Tercinta 2. Teman-Teman yang mendukung dan menyemangati saya KATA PENGANTAR Assalamu’alaikum Wr. Wb. Alhamdulillahi Rabbil‟alamin. Puji syukur kehadirat Allah Subhanahu wa Ta'ala, atas rahmat, karunia dan petunjuk-Nya sehingga tugas akhir berupa penelitian komunikasi dengan judul Tembok Dan Kritik Lingkungan Membaca Karya Street Art Di Desa ini dapat diselesaikan. Shalawat serta salam semoga selalu tercurah kepada Nabi Muhammad Shallallahu alaihi wasallam, tauladan umat manusia yang selalu berusaha menanamkan nilai-nilai kebenaran dalam kehidupan sehari-hari. Penelitian komunikasi ini disusun untuk memenuhi salah satu syarat dalam mencapai gelar kesarjanaan pada Program Studi Ilmu Komunikasi, Fakultas Psikologi dan Ilmu Sosial Budaya, Universitas Islam Indonesia. Hasil dari Penelitian ini diharapkan dapat bermanfaat bagi seluruh masyarakat pada umumnya, terutama pada kalangan pegiat kesenian khususnya. Penulis tidak dengan mudah menyelesaikan penelitian komunikasi ini tanpa adanya bantuan dari berbagai pihak selama proses penyelesaian projek komunikasi ini. Maka dengan segala kerendahan hati, penulis ingin mengucapkan terima kasih sebesar-besarnya kepada : 1. Dosen pembimbing penulis, Pak Ali Minanto yang telah bersedia menjadi dosen pembimbing dan telah memberikan arahan-arahan agar hasil penelitian menjadi baik. 2. Dosen pembimbing akademik, Pak Muzayin yang telah membimbing saya selama menjadi mahasiswa Ilmu Komunikasi Universitas Islam Indonesia 3. -

Eko Nugroho Ho Tzu Nyen Heman Chong Haegue Yang Ripped White Flags

Eko Nugroho Ho Tzu Nyen Heman Chong Haegue Yang Ripped White Flags For the people of Indonesia, real democracy only came with the Reformation of 1998, after the fall of Suharto. Since then we have been celebrating it and feeding it, though this relatively young system also brings big changes and massive challenges. While we are learning, understanding and educating ourselves, the forces of anarchy and the pressure from old powers still haunt this country. However, we, artists of the post-1998 Reformation generation, are not lonely; we stick together. This is the benefit of our democracy today. The project on the pages that follow is all about artists and art that reflect Indonesian society today. It’s about art that refuses to raise the white flag in the face of obstacles and that refutes that flag’s two primary significances: ‘surrender’ and ‘death’. We would never surrender under any pressure, and will keep our work ‘live’. Our work is to bring democracy into art, which could never happen here in Indonesia during the 31 years of Suharto’s reign. Curated by Eko Nugroho 48 ArtReview Asia Eko Nugroho Me, I like to criticise our everyday life through my work. It is kind of mirroring society and modern life today. Nugroho’s works are grounded in both local crafts, including batik and embroidery, and global popular culture, such as grati and comics. In 2000 Nugroho founded Daging Tumbuh, a collaborative zine. His work has been shown at the 55th Venice Biennale (2013) and at the Lyon Biennial (2009). Recent solo exhibitions include the Singapore Tyler Print Institute, the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris; Pekin Fine Arts, Beijing; Kiasma Museum of Contemporary Art, Helsinki; and Artotheek, The Hague.