Indonesian Art Today

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NUS Museum Wins Inaugural Award for Innovative Museological Practice

NUS Centre For the Arts For immediate release NUS Museum wins inaugural award For innovative museological practice International Committee of University Museums and Collections recognizes efforts to facilitate conversation between audiences and exhibitions Associate Professor Peter Pang, Associate Provost (Student Life), NUS, accepting the award from UMAC Chair Professor Hugues Dreyssé at NUS Museum, 10 May 2016. SINGAPORE, 10 May 2016 – NUS Museum’s prep-room is the first recipient of the University Museums and Collections (UMAC) Award for the most significant innovation or practice that has proved successful in a university museum or collection. Initiated in 2011, the prep-room is conceived as a means of exploring curatorial methods, developing content and scope and seeking audience participation in the lead-up to projects such as exhibitions and programmes. Employing mostly archival materials, curators present content, curatorial experiments and design ideas in an open gallery, inviting visitors to observe the exhibition-making process, engage with content, and potentially begin a long-term interest in the project. Since 2011, a total of ten projects have been incubated as prep-rooms at the Museum. Professor Hugues Dreyssé, Chairman of UMAC, shares, “The Board (of UMAC) salutes the museum's understanding of the basic principle of creating a contact between the audience and the museum, the creative approach to discussion between researchers, interns, artists and the public and the ease of adapting the idea to other museums.” In 2011, NUS Museum developed the notion of the prep-room from the museum’s work with archival materials and methods. With an interest in the Raffles Lighthouse, located on Pulau Satumu (Singapore), curators and collaborators spent eight months sourcing, categorizing and visually mapping archival materials ranging from 15th century cartographic maps to 19th century governmental declarations. -

8. E-Book BARA LAPAR JADIKAN PALU TARING

BARA LAPAR JADIKAN PALU COLOPHON TARING PADI Bara Lapar Jadikan Palu Editor I Gede Arya Sucitra Nadiyah Tunnikmah Penulis Bambang Witjaksono Mohamad Yusuf Aminudin TH Siregar Risa Tokunaga Desain & Tata Letak Kadek Primayudi Semua gambar dan foto diambil dari koleksi Taring Padi. Hak Cipta @ 2018 Galeri R.J. Katamsi ISI Yogyakarta Hak Cipta dilindungi oleh undang-undang. Dilarang memperbanyak atau memindahkan sebagian atau seluruh isi buku ini dalam bentuk apapun, baik secara elektronis maupun mekanis, termasuk memfotocopy, merekam atau dengan sistem penyimpanan lainnya, tanpa ijin tertulis dari penerbit. Penerbit: Galeri R.J. Katamsi, ISI Yogyakarta Jalan Parangtritis km 6,5 Sewon Bantul Yogyakarta www.isi.ac.id Cetakan Pertama, November 2018 Perpustakaan Nasional: Katalog Dalam Terbitan I Gede Arya Sucitra & Nadiyah Tunnikmah TARING PADI Bara Lapar Jadikan Palu Yogyakarta: Galeri R.J. Katamsi ISI Yogyakarta, 2018 128 hlm.; 15 cm x 21 cm ISBN: 978 - 602 - 53474 - 0 - 5 KPRP_Yustoni, Mereka yang Tanggung Jawab, Cat Genteng di atas Kain, 220 x 300 cm, 1998 4 7 Pengantar Kepala Galeri R.J. Katamsi ISI Yogyakarta 10 Pengantar Rektor ISI Yogyakarta 15 Bara Lapar Jadikan Palu, 20 Tahun Taring Padi Bambang Witjaksono 37 Taring Padi Berada Mohamad Yusuf 68 Deklarasi Taring Padi 71 Taring Padi Dalam Sejarah Seni Aminudin Th Siregar 87 The 20 Years of Taring Padi: Spirit of Solidarity and Political Imagination Crossing Borders Risa Tokunaga 106 Biodata Taring Padi 124 Tentang Penulis 126 Tim Kerja 128 Terima Kasih 5 Foto bersama di Gampingan, 2010 6 KPRP _Yustoni, Sedumuk Bhatuk, Cat Genteng di atas Kain, 220 x 300 cm, 1998 (Detail) 7 PENGANTAR Salam budaya, Puji syukur kita panjatkan kehadapan Tuhan Yang Maha Esa pun Maha Karya atas dianugerahkannya kesehatan dan kreativitas seni berlimpah pada kita semua. -

Introducing the Museum Roundtable

P. 2 P. 3 Introducing the Hello! Museum Roundtable Singapore has a whole bunch of museums you might not have heard The Museum Roundtable (MR) is a network formed by of and that’s one of the things we the National Heritage Board to support Singapore’s museum-going culture. We believe in the development hope to change with this guide. of a museum community which includes audience, museum practitioners and emerging professionals. We focus on supporting the training of people who work in We’ve featured the (over 50) museums and connecting our members to encourage members of Singapore’s Museum discussion, collaboration and partnership. Roundtable and also what you Our members comprise over 50 public and private can get up to in and around them. museums and galleries spanning the subjects of history and culture, art and design, defence and technology In doing so, we hope to help you and natural science. With them, we hope to build a ILoveMuseums plan a great day out that includes community that champions the role and importance of museums in society. a museum, perhaps even one that you’ve never visited before. Go on, they might surprise you. International Museum Day #museumday “Museums are important means of cultural exchange, enrichment of cultures and development of mutual understanding, cooperation and peace among peoples.” — International Council of Museums (ICOM) On (and around) 18 May each year, the world museum community commemorates International Museum Day (IMD), established in 1977 to spread the word about the icom.museum role of museums in society. Be a part of the celebrations – look out for local IMD events, head to a museum to relax, learn and explore. -

Call for Applications – CIMAM Travel Grants, Singapore | C-E-A

4/7/2017 Call for applications – CIMAM Travel Grants, Singapore | C-E-A < Tous les articles de la catégorie Annonces Call for applications – CIMAM Travel Grants, Singapore avril 24, 2017 // Catégorie Annonces, News Deadline to submit applications – 30th June 2017 24:00 CET Thanks to the generous support of the Getty Foundation, MALBA–Fundación Costantini, the Fubon Art Foundation and Alserkal Programming, CIMAM offers around 25 grants to support the attendance of contemporary art museum professionals to CIMAM’s 2017 Annual Conference The Roles and Responsibilities of Museums in Civil Society that will be held in Singapore, 10–12 November 2017. Grants are restricted to modern and contemporary art museum or collection directors and curators in need of financial help to attend CIMAM’s Annual Conference. Researchers and independent curators whose field of research and specialization is contemporary art theory, collections and museums are also eligible. Applicants should not be involved in any kind of commercial or for profit activity. While curators of all career levels are encouraged to apply, priority is given to junior curators (less than 10 years’ experience). More information http://c-e-a.asso.fr/call-for-applications-cimam-travel-grants/ 1/2 HOME Search MOBILITY NEWS By Topic 02.06.2017 Most Popular News By World Region CIMAM 2017 Conference in Singapore > Travel 03.01.2018 By Deadlines grants Plovdiv 2019 Foundation > artist in residence: ADATA AiR (Bulgaria) MOBILITY FUNDING CIMAM, International Committee for Read more » Museums and Collections of Modern 28.12.2017 MOBILITY HOT TOPICS Art, holds its 2017 Annual Conference December 2017 Cultural Mobility in Singapore, 10-12 November 2017. -

“The Great Archipelago,” Its Eighth Project

Kayu is pleased to present “The Great Archipelago,” its eighth project, which consists of an international group exhibition including contributions by Arahmaiani, Ashley Bickerton, Dora Budor, Marco Cassani, Rafram Chaddad + Rirkrit Tiravanija, Fendry Ekel, Michal Helfman, Michelangelo Pistoletto, Rochelle Goldberg, Filippo Sciascia, and Entang Wiharso. The exhibition is part of the first “Rebirth Forum–Sustainability Through Differences,”*a three-dayevent –29, 30, 31 October–which aim is to create a platform for public and private entities, individuals and institutions, engaged in daily practices of sustainability and coming from different fields: from energy to food, from production to intercultural dialogue, from design to agriculture, from culture to health. The exhibition is deeply inspired by the work of Michelangelo Pistoletto and reflects on the concept of the table as a domestic object and as a symbol of union. The exhibition will feature eleven tables designed by the aforementioned artists and produced in Indonesia. The tables exhibited will host one hundred guests during the aforementioned three-day event. After the conclusion of the forum all the tables will remain on view for the entire duration of the exhibition. Furthermore, the title of the exhibition refers to the title of Michelangelo Pistoletto’s artwork, Il Grande Arcipelago [The Great Archipelago], a mirror table conceived by the artist for this occasion and produced in Indonesia. The table represents the seas that touch Indonesia and it is part of the mirror table series that Pistoletto made and which looks at the sea as the ultimate cultural melting pot, a symbol of meeting between different cultures. Kayu is Lucie Fontaine’s branch in Bali and since its inception it presented solo exhibitions by Luigi Ontani, Radu Comșa, Ashley Bickerton as well as the international group shows Domesticity V, Domesticity VI, Domesticity VII, and Ritiro. -

The Rise of Private Museums in Indonesia

art in design The Rise of Deborah Iskandar Private Museums Art Consultant — Deborah Iskandar in Indonesia is Principal of ISA Advisory, which advises clients on buying and selling art, and building Until recently, the popular destinations for art lovers in Indonesia had been collections. An expert Yogyakarta, Bandung or Bali. But now things are rapidly changing as private art on Indonesian and international art, she museums are opening in cities all over Indonesia. A good example is Solo, a city in has more than 20 Central Java also known as Surakarta, which boasts an awe-inspiring combination years of experience in Southeast of history and culture. It offers many popular tourist attractions and destinations, Asia, heading including the Keraton Surakarta, and various batik markets. However, despite the both Sotheby’s and Christie’s historical and cultural richness of Solo, it was never really renowned for its art until Indonesia during recently, with luxury hotels increasingly investing in artworks and the opening of her career before 02 establishing ISA Art a new private museum. Advisory in 2013. She is also the Founder arlier this year, Solo finally got its own on those who are genuinely interested in increasing of Indonesian prestigious private museum called their knowledge about art. Luxury, the definitive Tumurun Private Museum. Opened in online resource for April, the Tumurun exhibits contemporary Tumurun prioritises modern and contemporary Indonesian’s looking E to acquire, build and and modern art from both international and local art so that the public, and the younger generation artists and is setting out to educate the people in particular, can learn and understand about style their luxury of Solo about how much art contributes and the evolution of art in Indonesia. -

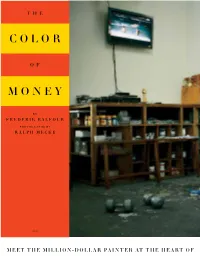

The-Color-Of-Money.Pdf

POURS TWO GLASSES FROM A BOTTLE OF 18-YEAR-OLD MACALLAN single-malt Scotch. He’s sitting poolside at his 1,000-square- meter villa on the outskirts of Yogyakarta, Indonesia, the eve- ning air rich with jasmine, frangipani and passion fruit, mingled with the sweet smoke from Masriadi’s clove cigarette. A shiny, new, 1,700-cubic-centimeter Harley-Davidson motor- cycle is parked at one end of his garden; a Balinese-style gazebo and shrine stand at the other. “Perhaps I have had success in my career,” the 40-year-old artist says. Masriadi is being modest. Fifteen years ago, he was hawking souvenir paintings to tourists in Bali for $20 a pop. Today, his canvases sell at blue-chip galleries for $250,000 to $300,000, and he’s the first living Southeast Asian artist whose work has topped $1 million at auction. Hence the Harley, the pool and the expensive Scotch. An obsessive and painstakingly slow painter, Masriadi turns out only eight to 10 canvases a year. His style is a cross between DC Comics (home to Batman, Superman and Wonder Woman), which he acknowledges as an inspiration, and the Colombian painter and sculptor Fernando Botero, whom he does not. Me- ticulously executed and ironic, his works feature preternatu- rally muscular figures with gleaming skin. His themes range from mobile phones and online gaming to political corruption and the pain of dieting. Deceptively simple at first glance, his works often evince trenchant political satire. Nicholas Olney, director of New York’s Paul Kasmin Gallery, recalls seeing an exhibition of the artist’s work for the first time at the Singapore Art Museum in 2008. -

The Artist As Researcher by Janneke Wesseling

Barcode at rear See it Sayit TheArt ist as Researcher Janneke Wesseling (ed.) Antennae Valiz, Amsterdam With contributions by Jeroen Boomgaard Jeremiah Day Siebren de Haan Stephan Dillemuth Irene Fortuyn Gijs Frieling Hadley+Maxwell Henri Jacobs WJMKok AglaiaKonrad Frank Mandersloot Aemout Mik Ruchama Noorda Va nessa Ohlraun Graeme Sullivan Moniek To ebosch Lonnie van Brummelen Hilde Van Gelder Philippe Va n Snick Barbara Visser Janneke Wesseling KittyZijlm ans Italo Zuffi See it Again, Say it Again: The Artist as Researcher Jan n eke We sse1 ing (ed.) See it Again, Say it Again: .. .. l TheArdst as Researcher Introduction Janneke We sseling The Use and Abuse of .. ...... .. .. .. .. 17 Research fo r Art and Vic e Versa Jeremiah Day .Art Research . 23 Hilde Va n Gelder Visual Contribution ................. 41 Ae rnout Mik Absinthe and Floating Tables . 51 Frank Mandersloot The Chimera ofMedtod ...... ........ ... 57 Jero en Boomgaard Reform and Education .. ...... ...... .. 73 Ruchama Noorda TheArtist as Researcher . 79 New Roles for New Realities Graeme Sullivan Visual Contribution .. .. .... .. .... .. 103 Ag laia Ko nrad Some Thoughts about Artistic . 117 Research Lonnie van Brummelen & Siebren de Haan Surtace Research . 123 Henri Jacobs TheArtist's To olbox .......... .......... 169 Irene Fortuyn Knight's Move . 175 The Idiosyncrasies of Artistic Research Ki tty Z ij 1 m a n s In Leaving the Shelter ................. 193 It alo Zu ffi Letterto Janneke Wesse6ng .......... 199 Va nessa Ohlraun Painting in Times of Research ..... 205 G ij s F r i e 1 ing Visual Contribution ........ .... ...... 211 Philippe Va n Snick TheAcademy and ........................... 221 the Corporate Pub&c Stephan Dillemuth Fleeting Profundity . 243 Mon iek To e bosch And, And , And So On . -

Laura Huertas Millán CV Education 2017 Phd, ENS Rue D'ulm, Beaux

Laura Huertas Millán CV b. in 1983, Bogotá, Colombia. Lives and works in Paris, France. [email protected] tel: + 33 (0) 667783951 www.laurahuertasmillan.com Education 2017 PhD, ENS rue d’Ulm, Beaux-Arts de Paris (SACRe program), Paris, France. 2014 Visiting fellow, Sensory Ethnography Lab, Harvard University, Cambridge, USA. 2012 Master´s degree, Le Fresnoy (summa cum laude), Tourcoing, France. 2009 MFA (summa cum laude), Beaux-Arts de Paris, France. Awards / Grants / Residences 2018 Research Grant, Centre national des arts plastiques, Paris, France Emerging Artist Award, Fontanals Art Foundation (CIFO), Miami, USA. Best Direction Prize, Pardo di domani competition, Locarno Film Festival, Switzerland. Best Film Tenderfilm Award, Tenderpixel, London, England. Best experimental film, Bogoshorts, Colombia. Shortlisted, Future Generation Art Prize, PinchuckArtCenter, Kiev, Ukraine. 2017 Best Film, National Competition, MIDBO, Bogota, Colombia. Grand Prix, Biennale de la Jeune Création Européenne (BJC), Montrouge, France. Best short film, Fronteira Film Festival, Goiânia, Brazil. Conseil départemental des Hauts-de-Seine Prize, Salon de Montrouge, France. 2016 Jury´s mention, Grand Prix international competition, Doclisboa, Lisboa, Portugal. Jury´s mention, Grand Prix French competition, FIDMarseille, Marseille, France. PhD Research Grant, PSL, Université Paris Sciences et Lettres, France. Production Grant, Film Study Center, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA. Post-production Grant, cinéma 93-CNC, France. Nominee, Rolex Mentor and Protégé initiative (Cinema), New York, USA. 2015 Residency, Fundación Arquetopia, Oaxaca, Mexico. Film Development Grant, Fondo Cinematográfico Colombiano, Bogota, Colombia. Production Grant, Film Study Center, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA. 2014 Jury´s mention, Bienal de la Imagen en movimiento, Buenos Aires, Argentina. PhD Research Grant, PSL, Université Paris Sciences et Lettres, France. -

Java Batiks to Be Displayed in Indonesian Folk Art Exhibit at International Center

Java batiks to be displayed in Indonesian folk art exhibit at International Center April 22, 1974 Contemporary and traditional batiks from Java will be highlighted in an exhibit of Indonesian folk art May 3 through 5 at the International Center on the Matthews campus of the University of California, San Diego. Some 50 wood carvings from Bali and a variety of contemporary and antique folk art from other islands in the area will also be displayed. Approximately 200 items will be included in the show and sale which is sponsored by Gallery 8, the craft shop in the center. The exhibit will open at 7:30 p.m. Friday, May 3, and will continue from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Saturday, May 4, and Sunday, May 5. Included in the batik collection will be several framed examples completed in the folk tradition of central Java by a noted batik artist, Aziz. Several contemporary paintings from artists' workshop in Java, large contemporary silk panels and traditional patterns made into pillows will also be shown. Wood pieces in the show include unique examples of ritualistic and religious items made in Bali. One of the most outstanding is a 75-year-old winged lion called a singa which is used to ward off evil spirits. The two-foot- high carved figure has a polychrome and gold-leaf finish. Among other items displayed will be carved wooden bells and animals from Bali, ancestral wood carvings from Nias island, leather puppets, food baskets and brass carriage lanterns from Java and implements for making batiks. -

Authentication, Attribution and the Art Market: Understanding Issues of Art Attribution in Contemporary Indonesia

Authentication, Attribution and the Art Market: Understanding Issues of Art Attribution in Contemporary Indonesia Eliza O’Donnell, University of Melbourne, Australia Nicole Tse, University of Melbourne, Australia The Asian Conference on Arts & Humanities 2018 Official Conference Proceedings Abstract The widespread circulation of paintings lacking a secure provenance within the Indonesian art market is an increasingly prevalent issue that questions trust, damages reputations and collective cultural narratives. In the long-term, this may impact on the credibility of artists, their work and the international art market. Under the current Indonesian copyright laws, replicating a painting is not considered a crime of art forgery, rather a crime of autograph forgery, a loophole that has allowed the practice of forgery to grow. Despite widespread claims of problematic paintings appearing in cultural collections over recent years, there has been little scholarly research to map the scope of counterfeit painting circulation within the market. Building on this research gap and the themes of the conference, this paper will provide a current understanding of art fraud in Indonesia based on research undertaken on the Authentication, Attribution and the Art Market in Indonesia: Understanding issues of art attribution in contemporary Indonesia. This research is interdisciplinary in its scope and is grounded in the art historical, socio-political and socio-economic context of cultural and artistic production in Indonesia, from the early twentieth century to the contemporary art world of today. By locating the study within a regionally relevant framework, this paper aims to provide a current understanding of issues of authenticity in Indonesia and is a targeted response to the need for a materials- evidence based framework for the research, identification and documentation of questionable paintings, their production and circulation in the region. -

Archival Pigment Print on Aluminum Protected with Transparent Acrylic 120 X 150 Cm Agan Harahap

Agan Harahap Old Master 2016 | Archival pigment print on aluminum protected with transparent acrylic 120 x 150 cm Agan Harahap Bounty Hunter 2016 | Archival pigment print on aluminum protected with transparent acrylic 155 x 100 cm Di era teknologi digital ini, citra menyebar di dunia maya secepat cahaya. Kecepatan, ilusi dan kesolidan realitas maya membuat kita kerap merasakannya sebagai realitas sesungguhnya. Tanpa pernah menyaksikan lukisan aslinya dan merasa berjarak dengan paradigma dunia seni ‘tinggi’ di Indonesia, Agan Harahap menemukan citra sosok-sosok karikatural yang dikenal sebagai identitas “blue-chip” lukisan Nyoman Masriadi. Lukisan- lukisan bercitra koboi-pemburu dan kesatria mirip samurai itu tahun lalu dipajang di sebuah galeri terkenal di New York. Agan Harahap “melukis” atau menafsir ulang citraan mashyur itu dengan perangkat lunak komputer. Kejanggalan yang ditemukan pada lukisan Masriadi diperbaiki menjadi citra fotografis yang lebih ‘sempurna’ dengan merekayasa sejumlah foto rujukan dan model citra temuan. Kendati tetap condong sebagai fiksi, karyanya memberi asosiasi tokoh yang benar-benar ada di dunia nyata. Karya olahan fotografinya menjadi parodi dari citra lukisan yang—entah dengan mekanisme apa—ditahbiskan sebagai “kandidat apresiasi” yang bernilai sangat tinggi. In this era of digital technology, an image multiplies in the virtual world in the speed of light. The speed, the illusion and the solidity of virtual world make us often feel it as a true reality. Since he never watched the real painting and still feels a distance from the paradigm of "high" art world in Indonesia, Agan Harahap found the image of caricature figures known as the "blue-chip" identity of Nyoman Masriadi's painting.