Reading the Songs of the Sage in Sequence: Preliminary Observations and Questions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adyar Pamphlets Theories About Reincarnation and Spirits No. 144 Theories About Reincarnation and Spirits by H.P

Adyar Pamphlets Theories About Reincarnation and Spirits No. 144 Theories About Reincarnation and Spirits by H.P. Blavatsky From The Path, November, 1886 Published in 1930 Theosophical Publishing House, Adyar, Chennai [Madras] India The Theosophist Office, Adyar, Madras. India OVER and over again the abstruse and mooted question of Rebirth or Reincarnation has crept out during the first ten years of the Theosophical Society's existence. It has been alleged on prima facie evidence, that a notable discrepancy was found between statements made in Isis Unveiled, Volume I, pp. 351-2, and later teachings from the same pen and under the inspiration of the same Master.[ See charge and answer, in Theosophist. August 1882] In Isis it was held, reincarnation is denied. An occasional return, only of “depraved spirits" is allowed. ' Exclusive of that rare and doubtful possibility, Isis allows only three cases - abortion, very early death, and idiocy - in which reincarnation on this earth occurs." (“C. C. M." in Light, 1882.) The charge was answered then and there as every one who will turn to the Theosophist of August, 1882, can see for himself. Nevertheless, the answer either failed to satisfy some readers or passed unnoticed. Leaving aside the strangeness of the assertion that reincarnation - i.e., the serial and periodical rebirth of every individual monad from pralaya to pralaya - [The cycle of existence during the manvantara - period before and after the beginning and completion of which every such "Monad" is absorbed and reabsorbed in the ONE -

Beautiful Family! Broadway/ First National Tour: Beautiful; Betty/ Ensemble

SARAH BOCKEL (Carole King) is thrilled to be back on the road with her Beautiful family! Broadway/ First National Tour: Beautiful; Betty/ Ensemble. Regional: Million Dollar Quartet (Chicago); u/s Dyanne. Rocky Mountain Repertory Theatre- Les Mis; Madame Thenardier. Shrek; Dragon. Select Chicago credits: Bohemian Theatre Ensemble; Parade, Lucille (Non-eq Jeff nomination) The Hypocrites; Into the Woods, Cinderella/ Rapunzel. Haven Theatre; The Wedding Singer, Holly. Paramount Theatre; Fiddler on the Roof, ensemble. Illinois Wesleyan University SoTA Alum. Proudly represented by Stewart Talent Chicago. Many thanks to the Beautiful creative team and her superhero agents Jim and Sam. As always, for Mom and Dad. ANDREW BREWER (Gerry Goffin) Broadway/Tour: Beautiful (Swing/Ensemble u/s Gerry/Don) Off-Broadway: Sex Tips for Straight Women from a Gay Man, Cougar the Musical, Nymph Errant. Love to my amazing family, The Mine, the entire Beautiful team! SARAH GOEKE (Cynthia Weil) is elated to be joining the touring cast of Beautiful - The Carole King Musical. Originally from Cape Girardeau, Missouri, she has a BM in vocal performance from the UMKC Conservatory and an MFA in Acting from Michigan State University. Favorite roles include, Sally in Cabaret, Judy/Ginger in Ruthless! the Musical, and Svetlana in Chess. Special thanks to her vital and inspiring family, friends, and soon-to-be husband who make her life Beautiful. www.sarahgoeke.com JACOB HEIMER (Barry Mann) Theater: Soul Doctor (Off Broadway), Milk and Honey (York/MUFTI), Twelfth Night (Elm Shakespeare), Seminar (W.H.A.T.), Paloma (Kitchen Theatre), Next to Normal (Music Theatre CT), and a reading of THE VISITOR (Daniel Sullivan/The Public). -

Spring 2021 Edition

Your word is a lampLamplight to guide my feet and a light for my path. ~Psalms 119:105 [email protected] Spring Edition Volume 10-Issue 02 Margaret Hudson Lamplight Editor Spotlight 1 Mother’s Day 2 Pastor’s Page 3 Marriage Ministry 4 Letter From Jesus 5 Young Adults… 6 What’s Happening 7 Featured Contributor D. Grady Scott, Pastor Editor/Contributor Margaret Hudson Staff / Contributor Carmen Wallace Cynthia Herring 1 Corinthians 6:14, “And God raised the Lord and will also raise us up by his own power.” Page 2 Lamplight - Spring 2021 Margaret Hudson Lamplight Editor Happy Mother’s Day Prayer for Mothers on Mother's Day Heaven Has Its Mother's Day Dear Heavenly Father, Heaven has its Mother's Day This special time of year Thank you for godly mothers who give and serve No matter how much pain we feel Our mothers are selflessly day after day. Please bless them for the always near important role they play in the lives of their children and family members. We cannot touch, we cannot see But in our hearts, they'll always be Just as mothers daily extend grace and Never forgotten, just gone away encouragement, Lord, return that grace and To meet again on judgment day encouragement back to them multiplied. Help them to give wise counsel, discipline, Heaven has its deliveries instruction, and to raise their children to know Of messages, chocolates, and flowers and love God. No doubt there's a busy postman Serving up all of ours Thank you for the example mothers are to their children and to others. -

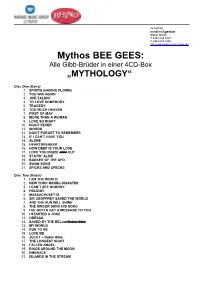

Mythos BEE GEES: Alle Gibb-Brüder in Einer 4CD-Box „MYTHOLOGY“

im Auftrag: medienAgentur Stefan Michel T 040-5149 1467 F 040-5149 1465 [email protected] Mythos BEE GEES: Alle Gibb-Brüder in einer 4CD-Box „MYTHOLOGY“ Disc One (Barry) 1. SPIRITS (HAVING FLOWN) 2. YOU WIN AGAIN 3. JIVE TALKIN’ 4. TO LOVE SOMEBODY 5. TRAGEDY 6. TOO MUCH HEAVEN 7. FIRST OF MAY 8. MORE THAN A WOMAN 9. LOVE SO RIGHT 10. NIGHT FEVER 11. WORDS 12. DON’T FORGET TO REMEMBER 13. IF I CAN’T HAVE YOU 14. ALONE 15. HEARTBREAKER 16. HOW DEEP IS YOUR LOVE 17. LOVE YOU INSIDE AND OUT 18. STAYIN’ ALIVE 19. BARKER OF THE UFO 20. SWAN SONG 21. SPICKS AND SPECKS Disc Two (Robin) 1. I AM THE WORLD 2. NEW YORK MINING DISASTER 3. I CAN’T SEE NOBODY 4. HOLIDAY 5. MASSACHUSETTS 6. SIR GEOFFREY SAVED THE WORLD 7. AND THE SUN WILL SHINE 8. THE SINGER SANG HIS SONG 9. I’VE GOTTA GET A MESSAGE TO YOU 10. I STARTED A JOKE 11. ODESSA 12. SAVED BY THE BELL – Robin Gibb 13. MY WORLD 14. RUN TO ME 15. LOVE ME 16. JULIET – Robin Gibb 17. THE LONGEST NIGHT 18. FALLEN ANGEL 19. RINGS AROUND THE MOON 20. EMBRACE 21. ISLANDS IN THE STREAM Disc Three (Maurice) 1. MAN IN THE MIDDLE 2. CLOSER THAN CLOSE 3. DIMENSIONS 4. HOUSE OF SHAME 5. SUDDENLY 6. RAILROAD 7. OVERNIGHT 8. IT’S JUST THE WAY 9. LAY IT ON ME 10. TRAFALGAR 11. OMEGA MAN 12. WALKING ON AIR 13. COUNTRY WOMAN 14. -

The Sons of God, Spirits, Spiritual and Spirits

11/03/18 Teacher: Bro. Buie The Israel of God 520 W. 138th Street, Riverdale, IL. 60827 Ph. 800-96-BIBLE KJV 1 Prayer: Psalms 116:1-5, 8 I love the LORD, because he hath heard my voice and my supplications. (2) Because he hath inclined his ear unto me, therefore will I call upon him as long as I live. (3) The sorrows of death compassed me, and the pains of hell gat hold upon me: I found trouble and sorrow. (4) Then called I upon the name of the LORD; O LORD, I beseech thee, deliver my soul. (5) Gracious is the LORD, and righteous; yea, our God is merciful. 8 For thou hast delivered my soul from death, mine eyes from tears, and my feet from falling. Cherub Angel SONS OF GOD: SPIRITS (ANGELS) Job 1:6-7 Now there was a day when the sons of God came to present themselves before the LORD, and Satan came also among them. (7) And the LORD said unto Satan, Whence comest thou? Then Satan answered the LORD, and said, From going to and fro in the earth, and from walking up and down in it. Notes: Sons of God = Angels Satan came also because even though he was cast down he is still a serving spirit. Angels are not the only sons of God and they do not procreate. God said…"Every seed after his own kind" If Angels were able to sleep with women, their children would also be spirit beings, meaning they wouldn't die and we would see them today. -

Jesus Said, “I Tell You the Truth, All the Sins and Blasphemies of Men Will Be Forgiven Them

“Unforgiven,” based on Mark 3:20-35 June 10, 2012 Pastor Jurchen The Unforgivable Sin! Jesus said, “I tell you the truth, all the sins and blasphemies of men will be forgiven them. But whoever blasphemes against the Holy Spirit will never be forgiven; he is guilty of an eternal sin.” Did you catch that, NEVER BE FORGIVEN. Imagine that: a sin so terrible that we would be separated from God forever, never more able to receive forgiveness. Lost and hopeless. I know of so many people who don’t believe in Jesus because they either are afraid of confessing their sins or choose to reject the notion that God does punish sins and his wrath burns against sin. In both of these cases the ultimate fear is that they won’t be forgiven. And Jesus here says that there is an unforgivable sin. So how do you know? How do you know that you haven’t committed this egregious sin against God’s law, how do you know that you haven’t committed the unforgivable sin? Because if you’re unsure, if you don’t know if you’ve blasphemed the Holy Spirit, then do you have assurance of your faith? Do you know for certain that you’re saved, that you’re in the clear when it comes to the unforgivable sin? Your eternity depends on the answer. So what does Jesus say about the unforgivable sin? Let’s unpack this. He says that it is blasphemy against the Holy Spirit. The high school youth would tell you that I’m a stickler for biblical vocabulary, so knowing what blasphemy is is critical, and knowing how it is done to the Holy Spirit is equally critical. -

Jewish Mourning Traditions

JEWISH MOURNING TRADITIONS Shmira / The Vigil (From Chevra Kadisha) When a person dies, the soul or neshama hovers around the body. This neshama is the essence of the person, the consciousness and totality, the thoughts, deeds, experiences and relationships. The body was its container and the neshama, now on the way to the Eternal World, refuses to leave until the body is buried. In effect, the totality of the person who died continues to exist for a while in the vicinity of the body. Jewish mourning ritual is therefore most concerned with the feelings of the deceased, not only the feelings of the mourners. How we treat the body and how we behave around the body must reflect how we would act around the very person himself. IMMEDIATELY AFTER DEATH Jacob is promised that when he dies, “Joseph’s hand shall close your eyes.” (Genesis 46:4). The 16th century “Code of Jewish Law” dictated that the eyes should be closed, arms and hands extended and brought close to the body and the lower jaw closed and bound. The body was placed on the floor, with the feet towards the door. The body was covered with a sheet and a lit candle placed near the head. The Midrash states that on Shabbat one does not close the eyes, bind the jaw or light a candle. Some Jewish communities would place potsherds on the eyes; Russians placed coins. Ancient superstitions in many cultures held that if the eyes were opened, the ghost of the deceased would return to fetch away another of the household. -

The Aural in Beloved Jody Morgan University of North Florida

University of North Florida UNF Digital Commons All Volumes (2001-2008) The sprO ey Journal of Ideas and Inquiry 2008 The Aural in Beloved Jody Morgan University of North Florida Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unf.edu/ojii_volumes Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Suggested Citation Morgan, Jody, "The Aural in Beloved" (2008). All Volumes (2001-2008). 12. http://digitalcommons.unf.edu/ojii_volumes/12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the The sprO ey Journal of Ideas and Inquiry at UNF Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Volumes (2001-2008) by an authorized administrator of UNF Digital Commons. For more information, please contact Digital Projects. © 2008 All Rights Reserved The Aural in Beloved Jody Morgan Faculty Sponsor: Dr. Samuel Kimball I know that my effort is to be like something that has probably only been fully expressed perhaps in music . Writing novels is a way to encompass this-this something. Toni Morrison (Mckay, 152) In an interview with Christina Davis, Toni Morrison describes her writing as “aural literature . because I do hear it” (230). Beloved is a particularly rich example of Morrison’s “aural literature”, literature which sounds and resounds. In an interview with Paul Gilroy, Morrison elaborates that these sounds are primarily musical: “My parallel is always the music, because all of the strategies of the art are there . music is the mirror that gives me the necessary clarity . .” (81). In Beloved, music is the medium through which the characters express their innermost painful memories, memories otherwise unable to be expressed in language. -

Beyond Death: Transition and the Afterlife

Beyond Death: Transition and the Afterlife Dr. Roger J. Woolger ‘He who dies before he dies, does not die when he dies’. Abraham of Santa Clara. ‘Zen has no other secrets than seriously thinking about birth and death’ Takeda Shingen ‘We are not dealing here with irreality. The mundus imaginalis is a world of autonomous forms and images...It is a perfectly real world preserving all the richness and diversity of the sensible world but in a spiritual state’. Henry Corbin By way of introduction I should say that I am a psychotherapist trained in Jungian psychoanalysis and various other modalities and that my current practice uses what is called ‘regression’ to early childhood, past life, inter-life and other transpersonal or ‘spiritual’ experiences. (In other contexts - see below - the word ‘regression’ can equally refer to what shamans call ‘journeying’) But I also hold degrees in the comparative phenomenology of religion, a subject that greatly illuminates the kind of areas that we are here today calling ‘beyond death’. Our starting point today has been the, by now, quite extensive documentation of so-called Near Death Experience (NDE); you have heard the detailed reports discussed by Dr. Fenwick’s and Dr. Powell’s reflections on similar experiences. It will already seem apparent that the scientific paradigm that seeks fully to explain such phenomena in materialistic terms is stretched beyond its limits. Not long ago, I saw a tape of a major British television program where a woman suffered a clinical NDE during an operation and reported, while ‘out of her body’ seeing an instrument in the operating room she could not possibly have seen while in her body and alive. -

Spirits Alive Souls on the Journey

Spirits Alive Souls on the Journey by Flora May Sherwin Litt-Irwin I will give you the treasures of darkness and riches hidden in secret places, so that you may know that it is I, the LORD, the God of Israel who call you by your name. Isaiah 45:3 The following is a prayer response to God, the Revealer of Secrets, inspired by the above scripture, written by Joyce Rupp in Fragments of Your Ancient Name Secrets from the storeroom of the divine, Disclosures as yet unnamed and restricted, Veiled concealments and awaiting revelation, All this rests within your enormous treasury. What could you be keeping hidden from me? What is disguised that can enhance my growth? How and when will you reveal something more? All these questions rise and fall from my mind While you, Revealer of Secrets, simply smile, Knowing full well no one hurries this process. Today: I open my spirit for further revelation. Spirits Alive - Souls on the Journey Sharing First Thoughts Travelling on a bus from Toronto to Hamilton, I was seated beside a young woman. I do not often speak much with a fellow passenger, but this time a conversation easily began. She was a second year engineering student at McMaster University. Inquiring about her plans, she shared with me her dream of going to Africa upon graduation. She had a deep desire to help the people by building up the infrastructure of a country there. I could hear the passion in her voice as she spoke. But, she had some doubts about how that would work out, being a woman in a traditionally male profession. -

Chart Info,Number One Chart Positions of Brothers Gibb Com…

The Brothers Gibb have had more than 200 number one charts positions (albums & singles) worldwide, themselves and/or with others acts singing their songs. Here are the number one positions we have compiled so far: Argentina Japan 1. SATURDAY NIGHT FEVER (1977) 110. Massachusetts (1967) 2. Too much heaven (1979) 111. Melody fair (1969) 3. SPIRITS HAVING FLOWN (1979) 112. SATURDAY NIGHT FEVER 4. SIZE ISN'T EVERYTHING (1993) (1977) 5. ONE NIGHT ONLY (1998) Malaysia Australia 113. Massachusetts (1967) 6. Massachusetts (1967) 7. I just want to be your everything - Andy Mexico Gibb (1977) 8. SATURDAY NIGHT FEVER (1977) 9. Stayin alive (1978) 114. SATURDAY NIGHT FEVER 10. SPIRITS HAVING FLOWN (1979) (1977) 11. GREATEST (1979) 115. Stayin alive (1978) 12. Woman in love - Barbra Streisand (1980) New Zealand 13. GUILTY - Streisand (1980) 14. Islands in the stream -Rogers, Parton (1983) 116. Spicks and specks (1966) 15. Chain reaction - Diana Ross (1986) 117. Massachusetts (1967) 16. Stayin alive - N'Trance (1995) 118. I started a joke (1968) 17. ONE NIGHT ONLY (1998) 119. Don't forget to remember (1969) 120. HERE AT LAST (1976) Austria 121. SATURDAY NIGHT FEVER (1977) 18. SATURDAY NIGHT FEVER (1977) 122. Stayin alive (1978) 19. Woman in love - Streisand (1980) 123. Too much heaven (1979) 20. Islands in the stream -Rogers, Parton 124. SPIRITS HAVING FLOWN (1983) (1979) 21. You win again (1987) 125. Tragedy (1979) 22. Ghetto Supastar - Islands... Pras (1998) 126. Woman in love - Streisand 23. ONE NIGHT ONLY (1998) (1980) 127. GUILTY - Streisand (1980) 128. Islands in the stream -Rogers, Belgium Parton (1983) 129. -

Spirits (Having Flown) Bee Gees

www.acordesweb.com Spirits (Having Flown) Bee Gees Álbum: Spirits Having Flown Compositor: Barry Gibb; Robin Gibb; Maurice Gibb Ano: 1978 - Duração: 5?13" INTRO: D7+ (4x) G9 Bm7 G6 G9 D7+ Ah! I never fell in love so easily. G9 Where the four winds blow, I carry on. F6 E7 Am C6 I'd like to take you where my spirit flies, through the empty skies. F7+ F6 G9 A We go alone never before having flown D7+ Faster than lightening is this heart of mine. G9 In the face of time, I carry on. F6 E7 I'd like to take you where my rainbow ends. Am C6 Be my lover friend. F7+ F6 G9 A Encuentra muchas canciones para tocar en Acordesweb.com www.acordesweb.com We go alone never before having flown Dm Gm7 C7 Dm7 I am your hurricane, your fire in the sun. Gm7 F G How long must I live in the air? Em Am7 D G You are my paradise, my angel on the run. Cm G How long must I wait? Cm G It's the dawn of the feeling that starts F6 G9 From the moment you're there. Interlúdio: (D7+)3x F#7 Bm Bm (D7+)3x F#7 Bm G D A7/4 A7/4 A7 A7 A7 D7+ You'll never know what you have done for me. G9 You broke all those rules I live upon. F6 E7 I'd like to take you to my Shangri-la, Am C6 F7+ neither here nor far, away from home F6 G9 A never before having flown.