HIGHER Education the Purpose and Function of an Adventist APPROACH to the Adventist Teaching Accrediting Psychology Association the JOURNAL OF

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Andrews University Seminary Studies for 1983

Andrews University SEMINARY STUDIES Volume 21 Number 3 Autumn 1983 Andrews University Press ANDREWS UNIVERSITY SEMINARY STUDIES The Journal of the Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary of Andrews University, Berrien Springs, Michigan 49104, U.S.A. Editor: KENNETH A. STRAND Associate Editors: JAMES J. C. COX, RAOUL DEDEREN, LAWRENCE T. GERATY , GERHARD F. HASEL, WILLIAM H. HESSEL, GEORGE E. RICE, LEONA G. RUNNING Book Review Editor: WILLIAM H. SHEA Editorial Assistant: ELLEN S. ERBES Circulation Manager: ELLEN S. ERBES Editorial and Circulation Offices: AUSS, Seminary Hall, Andrews University, Berrien Springs, MI 49104, U.S.A. ANDREWS UNIVERSITY SEMINARY STUDIES publishes papers and brief notes on the following subjects: Biblical linguistics and its cognates, Biblical theology, textual criticism, exegesis, Biblical archaeology and geography, ancient history, church history, systematic theology, philosophy of religion, ethics, history of religions, missiology, and special areas relating to practice of ministry and to religious education. The opinions expressed in articles, brief notes, book reviews, etc., are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the editors. Subscription Information: ANDREWS UNIVERSITY SEMINARY STUDIES iS published in the Spring, Summer, and Autumn. The subscription rate for 1983 is as follows: Foreign U.S.A. (in U.S.A. funds) Regular Subscriber $10.00' $11.50' Institutions (including Libraries) 12.50' 14.00' Students 8.00' 9.50' Retirees 8.00' 9.50' (Price for Single Copy is $5.00) 'NOTE: These are net rates for prepaid orders. A handling and service fee of $1.50 will be added if orders are to be billed. Subscribers should give full name and postal address when paying their subscriptions and should send notice of change of address at least five weeks before it is to take effect (old address as well as new address must be given). -

Brownsberger, Sidney (1845–1930)

Brownsberger, Sidney (1845–1930) MICHAEL CAMPBELL Michael Campbell Sidney Brownsberger was an Adventist educator and administrator. He played a significant role during the early development of Battle Creek College (Andrews University) and Healdsburg College (Pacific Union College). He was considered a “pioneer” in the development of Adventist education.1 Early Life, Marriage, and Family Sidney Brownsberger was the youngest of eight children born to John and Barbara Brownsberger. The family migrated westward from Pennsylvania to Ohio where Sidney was born September 20, 1845.2 He completed his early studies at Baldwin University in 1865 and then went on to graduate with a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of Michigan. While he was a student in Ann Arbor, he heard about Seventh- day Adventist beliefs from another young man who was not himself an Adventist. Brownsberger contacted the denomination and requested literature. When he received Adventist literature, he was challenged to study the Bible carefully.3 Without so much as a single Bible study, he started keeping the seventh-day Sabbath in 1868 during his junior year. Upon Sidney Brownsberger graduation he served as superintendent of schools in Photo courtesy of Center for Adventist Research. Maumee, Ohio and then Delta, Ohio.4 In 1873 church leaders invited Brownsberger to come church headquarters to lead the nascent Battle Creek College. It was hoped that with his educational background he could provide more “opportunity for the study of the languages, and other high branches.”5 During that first year (1873-1874) he served for one term as secretary of the General Conference. -

The Historical Development of the Religion Curriculum at Battle Creek College, 1874-1901

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertations Graduate Research 2001 The Historical Development of the Religion Curriculum at Battle Creek College, 1874-1901 Medardo Esau Marroquin Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations Part of the Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, Education Commons, and the History of Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Marroquin, Medardo Esau, "The Historical Development of the Religion Curriculum at Battle Creek College, 1874-1901" (2001). Dissertations. 558. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations/558 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your interest in the Andrews University Digital Library of Dissertations and Theses. Please honor the copyright of this document by not duplicating or distributing additional copies in any form without the author’s express written permission. Thanks for your cooperation. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

Southern Tidings for 1984

JUNE, 1984 SOUTHERN AFT .OAL C...1,..AN OF THE 50,HF RN 050.. CONFERENCE OF SEVEN,. OP, ADVENT STS ks We° W The Dream Continues The Dream Continues by John M. Lew Nestled among the Blue Ridge Mountains of up work in western North Carolina. Spalding western North Carolina is a 103-bed hospital, an contacted Brownsberger concerning the academy with 200 students, and a 165-student property. Mrs. White was consulted, and, with elementary school. And that is only the her encouragement, the farm was purchased for beginning. Also located there is an 875-member $5,000. church, a health food store, numerous From that beginning, 74 years ago, Fletcher physicians' offices, a farm, small press, bakery, has grown into a successful and respected and pharmacy. medical and educational center. Behind the development of this 1,000-acre institution is a story steeped with history. In Within a 25-mile radius of Fletcher Hospital addition to being an educator, writer, and and Academy live more than 3,250 Seventh-day editor, A. W. Spalding was a colporteur. As he Adventists, most of them belonging to canvassed his way down the mountain roads of congregations spawned by the Fletcher church. rural Henderson County he learned of a New Medical Facility Planned 450-acre farm for sale. Ellen White had visited the area and encouraged Sidney Brownsberger, For the past five years plans have been first president of Battle Creek College, to take underway to construct a new hospital on Approximately 1,500 students have graduated from Fletcher Academy. Enrollment for the 1984-85 school year is projected at 200. -

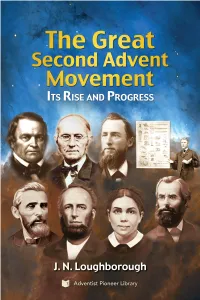

The Great Second Advent Movement.Pdf

© 2016 Adventist Pioneer Library 37457 Jasper Lowell Rd Jasper, OR, 97438, USA +1 (877) 585-1111 www.APLib.org Originally published by the Southern Publishing Association in 1905 Copyright transferred to Review and Herald Publishing Association Washington, D. C., Jan. 28, 1909 Copyright 1992, Adventist Pioneer Library Footnote references are assumed to be for those publications used in the 1905 edition of The Great Second Advent Movement. A few references have been updated to correspond with reprinted versions of certain books. They are as follows:— Early Writings, reprinted in 1945. Life Sketches, reprinted in 1943. Spiritual Gifts, reprinted in 1945. Testimonies for the Church, reprinted in 1948. The Desire of Ages, reprinted in 1940. The Great Controversy, reprinted in 1950. Supplement to Experience and Views, 1854. When this 1905 edition was republished in 1992 an additional Preface was added, as well as three appendices. It should be noted that Appendix A is a Loughborough document that was never published in his lifetime, but which defended the accuracy of the history contained herein. As noted below, the footnote references have been updated to more recent reprints of those referenced books. Otherwise, Loughborough’s original content is intact. Paging of the 1905 and 1992 editions are inserted in brackets. August, 2016 ISBN: 978-1-61455-032-7 4 | The Great Second Advent Movement J. N. LOUGHBOROUGH (1832-1924) Contents Preface 7 Preface to the 1992 Edition 9 Illustrations 17 Chapter 1 — Introductory 19 Chapter 2 — The Plan of Salvation -

Ellen White: Woman of Vision

Ellen White: Woman of Vision Arthur L. White 2000 Copyright © 2017 Ellen G. White Estate, Inc. Information about this Book Overview This eBook is provided by the Ellen G. White Estate. It is included in the larger free Online Books collection on the Ellen G. White Estate Web site. About the Author Ellen G. White (1827-1915) is considered the most widely translated American author, her works having been published in more than 160 languages. She wrote more than 100,000 pages on a wide variety of spiritual and practical topics. Guided by the Holy Spirit, she exalted Jesus and pointed to the Scriptures as the basis of one’s faith. Further Links A Brief Biography of Ellen G. White About the Ellen G. White Estate End User License Agreement The viewing, printing or downloading of this book grants you only a limited, nonexclusive and nontransferable license for use solely by you for your own personal use. This license does not permit republication, distribution, assignment, sublicense, sale, preparation of derivative works, or other use. Any unauthorized use of this book terminates the license granted hereby. Further Information For more information about the author, publishers, or how you can support this service, please contact the Ellen G. White Estate at [email protected]. We are thankful for your interest and feedback and wish you God’s blessing as you read. i Contents Information about this Book . .i Introduction . xv Ellen G. White and Her Writings . xv Foreword ........................................... xvii About The Author . xx Chapter 1—The Time Was Right. 22 Ellen’s Developing Christian Experience . -

MOVEMENT of DESTINY / Fy

MOVEMENT OF DESTINY / fy- ,40) Gt) Ir ' a IEW AND HERALD PUB. ASSN. Adventism in Complete Conspectus Mediating Before Judgment Bar of God.—Of all the sublime themes portrayed by Adventist Artist Harry Anderson, none is more lofty and meaningful than the frontispiece appearing op- posite this page. It depicts Christ—our ineffable Mediator-Priest— pleading our cases before the Judgment Seat of God. And this in the innermost sanctum of the sacred Command Center of all re- demptive activity, positioned in the heavenly Sanctuary above. Applies Benefits of His Atonement.—The Atoning Act of the Cross having been completed on Calvary—where Christ offered Himself as the "Lamb of God, which taketh away the sin of the world"—He now ministers the benefits of that unutterably sacred transaction. Time and Circumstance Established.—Christ stands with nail- scarred hands before the Mercy Seat, overspreading the transcend- ent law of God. Covering cherubim gaze with ceaseless wonder at the infinite love graven forever in those sin-wrought scars. Christ's very position and solemn activity identify the time and circum- stance—today, in God's great Judgment Hour. Embraces Complete System of Truth.—But there is vastly more. That last judgment scene depicts the central, all-embracing truth of Adventism. Within it is compassed a complete system of truth— every phase of Present Truth. It forms the very foundation of our faith, the center and circumference of every saving principle and provision. Righteousness by Faith at Its Highest.—Here Righteousness by Faith centers in and emanates from Christ as "all the fulness of the Godhead bodily." Here the outreach of believing faith, as a sweet-smelling savor, rises from earth below to the throne of God in heaven above. -

Light Bearers to the Remnant

Light BearersAR qf to the Remnant Light Bearers to the Remnant Denominational History Textbook for Seventh-day Adventist College Classes by R. W. Schwarz Prepared by the Depai iment of Education General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists PACIFIC PRESS PUBLISHING ASSOCIATION Mountain. View, California Omaha, Nebraska Oshawa, Ontario 1919 Copyright © 1979 by Pacific Press Publishing Association Litho in United States of America All Rights Reserved Design by Ichiro Nakashima Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 78-70730 FOREWORD Seventh-day Adventists must never forget the precious heritage that is ours. The message we refer to affectionately as the "Three Angels' Mes- sages," or simply as "the truth," has come to us as a legacy of long hours and days of prayer and study by men and women of God. The organization of our church is not the result of happenstance—God used men and women of commitment and ability to design the church structure that has served so effectively through the years. Light bearers these men and women were, indeed. They were God-led, God-blessed light bearers— light bearers who bore the torch gloriously through the years. We pause a moment to honor their memory—to pay tribute to all who were used of God to accomplish so much for the cause of present truth. The Seventh-day Adventist Church is not in the world today only as another ecclesiastical organization. The advent movement was heaven- born. It has been heaven-blessed through the decades of its existence and, thank God, it is heaven-bound. The message that has made us a people is a Christ-centered, Bible-based message. -

Bell, Goodloe Harper (1832–1899)

Bell, Goodloe Harper (1832–1899) MICHAEL CAMPBELL Michael Campbell As the founding teacher of the denomination’s first official sponsored school, Goodloe Harper Bell is considered by some historians as the “founder” of the educational work of the Seventh-day Adventist Church.1 Despite earlier attempts, Bell founded the first permanent Adventist school in Battle Creek, Michigan. His efforts also included educational administration, serving as an author and editor (including numerous textbooks), and an active promoter of the Sabbath School. He was remembered by Drury R. Davis as a quiet and unassuming person who was “the least appreciated man” of the early Adventist pioneers.2 Early Life and Family Goodloe Harper Bell’s family came from New England and migrated westward. He was the oldest of ten children born to David and Lucy Ann (née Blodgett) Bell in Watertown, New York, on April 7, 1832. His father was originally from Vermont, and his mother from Massachusetts.3 He moved west with his family, settling in Ottawa County, Michigan. Here he farmed and worked as a teacher and inspector of the schools in the counties around Grand Rapids from 1854 through the 1860s. At one point Bell studied at the reform minded Oberlin College. In his early years he was a Baptist and later became a Disciple.4 Goodloe Harper Bell Olsen Family Photograph Album, University Libraries, Loma Linda At age 19 he taught at a small country school where he University, accessed December 18, 2020. met Catherine Mary Stuart5 (1836-1866) who he married at age 21. Together they had four children: Clara A. -

Manual Training: Its Role in the Development of the Seventh-Day Adventist Educational System

University of Northern Iowa UNI ScholarWorks Dissertations and Theses @ UNI Student Work 1987 Manual training: Its role in the development of the Seventh-Day Adventist educational system Gerald Wayne Coy University of Northern Iowa Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Copyright ©1987 Gerald Wayne Coy Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/etd Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons, Educational Methods Commons, and the Vocational Education Commons Recommended Citation Coy, Gerald Wayne, "Manual training: Its role in the development of the Seventh-Day Adventist educational system" (1987). Dissertations and Theses @ UNI. 873. https://scholarworks.uni.edu/etd/873 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses @ UNI by an authorized administrator of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

California Conference

Image not found or type unknown California Conference RAYMOND D. TETZ Raymond D. Tetz has served as director of Communication and Community Engagement for the Pacific Union Conference since 2015. He served as vice president for strategic communication and corporate development at the Adventist Development and Relief Agency (ADRA) from 1986 to 1995. For two decades, he successfully operated a consulting and media production company that served dozens of Adventist organizations and ministries. Tetz began his ministry in the Southern California Conference, initially serving as a pastor, Bible teacher, and youth director. The California Conference was a unit of church organization that initially comprised the state of California. In later organizational rearrangements it also included at times Nevada, Utah, and Arizona. It was active from 1869 to 1932. Four conferences now cover the state of California: Northern, Central, Southeastern, and Southern, and these conferences are treated in separate articles. This article deals with the beginnings of the Adventist work in California and developments in the history of the California Conference until it was dissolved in 1932. Origins The earliest evidence of a Seventh-day Adventist presence in California comes in two letters from Daniel Eaton published in the Review and Herald in 1855. Eaton, located in Yreka, Siskiyou County in the northernmost part of the state, just south of the Oregon border, wrote that he did not have “the privilege of meeting with those of like precious faith.”1 In 1859 Merritt G. Kellogg, stepbrother of John Harvey Kellogg, traveled overland to California by wagon with his wife and children, settling in San Francisco. -

Of Seventh-Day Adventists

Origin and History of Seventh-day Adventists VOLUME Two J< !? 4L These happy faces of Solomon Island natives from the Batuna Training School, traveling to a mission conference in their former headhunting canoes, testify to the converting power of the gospel. COPYRIGHT © 1962 BY THE REVIEW AND HERALD PUBLISHING ASSOCIATION WASHINGTON, D.C. (OFFSET IN U.S.A.) Origin and History of Seventh-day Adventists A revision of the book Captains of the Host VOLUME TWO by Arthur Whitefield Spalding REVIEW AND HERALD PUBLISHING ASSOCIATION WASHINGTON, D.C. CONTENTS Chapter Page 1. Tent and Camp Meetings 7 2. Successors to the Pioneers 21 3. Instructing the Youth 61 4. Tract and Colporteur Work 79 5. Christian Education 91 6. Extending the Educational System I11 7. Hymns of the Advent 129 8. Pacific Coast Evangelism 141 9. Into the Southland 167 10. The Wider Vision 191 11. The Fateful Eighties 213 12. Reception in Russia 225 13. Religious Liberty 239 14. Subversive Elements 263 15. The Issues of 1888 281 16. The Southern Hemisphere 305 17. Founding Medical Institutions 327 18. American Negro Evangelism 341 19. The Church School Movement 353 CHAPTER 1 TENT AND CAMP MEETINGS HE holding of evangelistic meetings in tents was an early Seventh-day Adventist enterprise. They had the Texample of Miller and Himes in the 1844 movement, and of other Adventist lecturers since. Indeed, the first such tent used by Seventh-day Adventists was purchased from the first- day Adventists, who found it difficult to support and meager in results. In May of 1854, James and Ellen White, Loughborough, Cornell, Frisbie, and Cranson were holding meetings in Wash- tenaw, Ingham, and Jackson counties in Michigan.