Maritime Relation of Kalinga with Srilanka

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sun Temple, Konark

Sun Temple, Konark March 11, 2021 About Sun Temple, Konark Konark Sun Temple, located in the eastern State of Odisha near the sacred city of Puri, is dedicated to the sun God or Surya. It is a monumental representation of the sun God Surya’s chariot; its 24 wheels are decorated with symbolic designs and it is led by a team of six horses. It is a masterpiece of Odisha’s medieval architecture and one of India’s most famous Brahman sanctuaries. The Konark temple is widely known not only for its architectural grandeur but also for the intricacy and profusion of sculptural work. It marks the highest point of achievement of Kalinga architecture depicting the grace, the joy and the rhythm of life all its wondrous variety. The temple declared a world heritage by UNESCO was built in A.D. 1250, during the reign of the Eastern Ganga King Narasimhadeva-I (A.D. 1238-64). There are two rows of 12 wheels on each side of the Konark sun temple. Some say the wheels represent the 24 hours in a day and others say the 12 months. The seven horses are said to symbolize the seven days of the week. Sailors once called this Sun Temple of Konarak, the Black Pagoda because it was supposed to draw ships into the shore and cause shipwrecks. The Konark is the third link of Odisha’s Golden Triangle. The first link is Jagannath Puri and the second link is Bhubaneswar (Capital city of Odisha). This temple was also known as Black Pagoda due to its dark color and used as a navigational landmark by ancient sailors to Odisha. -

Ace Expedition India Tours & Travels

+91-9090551212 Ace Expedition India Tours & Travels https://www.indiamart.com/ace-expedition/ Providing car rental services, hotel booking services, guide services etc. About Us Now days, Travel is an urge for life which gives experience,knowledge and peace in mind. Travel is one of the life greatest joys. And this joy can be better enjoyed when it is perfectly organized. To have a perfectly organized trip, it needs a highly experienced hand We are one of India's leading travel-service-providers, specialized in providing customized travel services to tourists visiting the Indian Sub-Continent Specially Orissa with neighboring provinces like Chhattisgarh, Bengal. Jharkhand which are still very much unexplored part of India. Our zeal and commitment to our customers has empowered our vision to lead with exemplifying excellence. As a responsible travel company, we lay great emphasis on responsible and mindful travel that calls for protecting the local environment and culture. It is our constant endeavor to make positive contribution to the local ethos, customs and community, thereby ensuring a rewarding, inspiring and positive travel experience. We believe that as a reputed travel-service-provider, our success relies on our strong team to ensure that we meet all of your requirements and exceed your expectations. The major part played in the success of the firm is by the experienced & dedicated personnel having excellent track record in the respected fields that puts their all efforts to address our valuable client’s demands. Our services -

Proposal Under Demand No-07-3054-04-337-0865-21007'District Head Quarter Road for the Year 2019-20 SI

Proposal under Demand No-07-3054-04-337-0865-21007'District Head Quarter Road for the year 2019-20 SI. Name of the Amount Name of the Work No. (R&B) Division (Rs. In lakh) 1 2 3 4 S/R to New Jagannath Sadak from 0/630 to Q/660km ( Such as providing 1 Puri 4.76 Cement Concrete pavement at Chandanpur Bazar Portion ) S/R to New Jagannath Sadak from 0/665 to 0/695km ( Such as providing 2 Puri 4.91 Cement Concrete pavement at Chandanpur Bazar Portion ) Construction of entry gate on approach to Makara Bridge at ch,23/80km of New 3 Puri 4.23 Jagannath Sadak, Puri S/r ro New Jagannath Sadak from 14/070 to 14/240 Km such as construction of 4 Puri 4.82 Toe-wall & Packing on right side Construction of Retaining wall in U/S of Ratnachira Bridge at 13/290Km of New 5 Puri 4.98 Jagannath Sadak 6 Puri S/R to Jagannath Sadak road {Such as construction of Toe-wall at 2/300 Km) 4.74 Providing temporary Bus parking at Chupuring & approach road to Melana 7 Puri padia Jankia Gadasahi near New Jagannath Sadak for the visit of Hon’ble Chief 2.57 Minister of Odisha on 20.02,2019 Providing temporary Helipad ground Jankia Gadasahi near New Jagannath 8 Puri 3.00 Sadak for the visit of Hon'ble Chief Minister of Odisha on 20.02.2019 Providing temporary parking at Jankia Gadasahi near New Jagannath Sadak for 9 Puri 2.41 the visit of Hon'ble Chief Minister of Odisha on 20.02.2019 Providing temporary parking at Kanas side & Gadasahi near New Jagannath 10 Puri 4.88 Sadak for the visit of Hon'ble Chief Minister of Odisha on 20.02.2019 Repair of road from Hotel Prachi to -

2018 Excursion Tour Packages (Ex – Bhubaneswar)

HOCKEY WORLD CUP – 2018 EXCURSION TOUR PACKAGES (EX – BHUBANESWAR) Tour – 2: Raghurajpur – Puri - Konark – Pipili & back Tour duration: (09.00 a.m. to 08.45 p.m.) Package cost -: Rs.1335/- per head for Domestic Tourist Rs.1980/- per head for International Tourist ITINERARY Departure: 9.00 a.m. Kalinga Stadium Arrival: 10.30 a.m. Raghurajpur. Departure: 11.30 a.m. Raghurajpur. Arrival: 12 noon Jagannath Temple, Puri. Departure: 1.30 p.m. Jagannath Temple. Arrival: 1.45 p.m. Panthanivas Puri. (1.45 p.m. to 2.45 p.m. – Lunch at Panthanivas Puri and visit Panthanivas exclusive beach) Departure: 2.45 p.m. Puri beach. Arrival: 3.30 p.m. Chandrabhaga beach, Konark. Departure: 3.45 p.m. Chandrabhaga beach. Arrival: 4.00 p.m. Interpretation Centre, Konark & visit Sun Temple, Konark. Departure: 5.45 p.m. Sun Temple, Konark. Arrival: 7.15 p.m. Pipili. Departure: 7.45 p.m. Pipili. Arrival: 8.45 p.m. Kalinga Stadium. (Tour ends) Information about the places being visited in the programme -: • Raghurajpur - Artisans Pattapainting Village. • Jagannath Temple – Monument of 12th Century A.D. – One of the 4 dhams (Holy pilgrimage). • Puri beach - Beach on eastern sea coast where one can witness both sunrise and sunset. • Chandrabhaga beach - Famous for rising sun. • Sun Temple - Monument of 13th Century A.D. – The only World Heritage Site in Odisha. • Pipili – Famous for Appliqué work. Package Includes -: Ac Transport, Food (Only Lunch), 2 bottle Mineral Water per person, Entry fee & Guide service. Condition -: • Package shall be operational subject to minimum 8 person. -

The Architectural Study of Sun Temples in India: Based on Location, Construction Material and Spatial Analysis Study

International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, Volume 11, Issue 1, January 2021 331 ISSN 2250-3153 The Architectural Study of Sun Temples in India: Based on Location, Construction Material and Spatial Analysis Study Ar. Swarna Junghare Amity school of architecture and planning Amity University Raipur, Chhattisgarh DOI: 10.29322/IJSRP.11.01.2021.p10935 http://dx.doi.org/10.29322/IJSRP.11.01.2021.p10935 Abstract-Religious places are most important constructions in India in every religion. In Hindu religion, the temples have supreme importance and different god and goddesses like Vishnu, Mahadeva, et. Are being worshiped. among them we are focusing on sun temples because they are believed to be built either because of some vow or to celebrate victory. Concept behind building sun temple is sun as a celestial body in universe, earth’s rotation around sun, period of completion of one rotation. elements of ornamentation are focused on the above-mentioned factors. In India the origin of the worship of the Sun is several centuries old. Sun temples are constructed in different time period by various dynasties. The study of sun temples in India is based on their location, spatial arrangement, historical background, construction material, time line, evolution and ornamentation. By comparing above mentioned parameters, we can find out over the period of time changes occurred in the construction of the sun temple in India. This study helps in the construction of contemporary sun temples. Index Terms - Architectural Details, India, Light, Sun Temple, time line I INTRODUCTION The history of India is very old and from historical time in India, religion, culture, festivals plays important role. -

56 KONARK: INDIAN MONUMENTS Aparajita Sharma

International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Modern Education (IJMRME) Impact Factor: 7.315, ISSN (Online): 2454 - 6119 (www.rdmodernresearch.org) Volume 4, Issue 2, 2018 KONARK: INDIAN MONUMENTS Aparajita Sharma Gurukul Mahila Mahidayalaya Raipur, Pt. Ravishankar Shukla University, Raipur, Chhattisgarh Cite This Article: Aparajita Sharma, “Konark: Indian Monuments”, International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Modern Education, Volume 4, Issue 2, Page Number 56-62, 2018. Copy Right: © IJMRME, 2018 (All Rights Reserved). This is an Open Access Article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium provided the original work is properly cited. Abstract: Caring and preservation of Indian medieval monuments and sculptures is a necessary step towards their survival and prolonged exposure to the natural processes The Historical Monuments (HM)and Ancient Heritage Structures (AHS) severally affected by environmental, region. conditions prevailing in the ancient medieval Kalinga Architecture, KONARK, nearer to The Chandrabhaga shoreline Bay of Bensal which is dedicated to SUN (God Surya), declared UNESCO as World Heritage Site” have been critically analyzed and interpreted with a view of conservation and protective measures in caring of monuments. The study reveals that survival structure largely influenced by physical and chemical factors which causes the etching and deterioration of stones. It has been observed that mineralogical -

Research Setting

S.K. Acharya, G.C. Mishra and Karma P. Kaleon Chapter–6 Research Setting Anshuman Jena, S K Acharya, G.C. Mishra and Lalu Das In any social science research, it is hardly possible to conceptualize and perceive the data and interpret the data more accurately until and unless a clear understanding of the characteristics in the area and attitude or behavior of people is at commend of the interpreter who intends to unveil an understanding of the implications and behavioral complexes of the individuals who live in the area under reference and from a representative part of the larger community. The socio demographic background of the local people in a rural setting has been critically administered in this chapter. A research setting is a surrounding in which inputs and elements of research are contextually imbibed, interactive and mutually contributive to the system performance. Research setting is immensely important in the sense because it is characterizing and influencing the interplays of different factors and components. Thus, a study on Perception of Farmer about the issues of Persuasive certainly demands a local unique with natural set up, demography, crop ecology, institutional set up and other socio cultural Social Ecology, Climate Change and, The Coastal Ecosystem ISBN: 978-93-85822-01-8 149 Anshuman Jena, S K Acharya, G.C. Mishra and Lalu Das milieus. It comprises of two types of research setting viz. Macro research setting and Micro research setting. Macro research setting encompasses the state as a whole, whereas micro research setting starts off from the boundaries of the chosen districts to the block or village periphery. -

Studies on Primary Productivity of Bay of Bengal at Chandrabhaga Sea-Shore, Konark, Odisha

International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, Volume 5, Issue 2, February 2015 1 ISSN 2250-3153 Studies on Primary Productivity of Bay of Bengal at Chandrabhaga Sea-Shore, Konark , Odisha Ashabari Sahoo and A.K.Patra P.G. Department of Zoology, Utkal University, Vanivihar, Bhubaneswar, Orissa, India Abstract- Primary production refers to estimation of the ability of from fresh-water to estuarine and from estuarine to marine water an ecosystem to fabricate, at the expense of external energy both body (Dash et al., 2011). radiant and chemical, primary organic compounds of high The present study deals with gross, net and community chemical potentials for further transformation and flow to higher productivity of marginal seawater of Bay of Bengal at system levels. In the present investigation the light dark oxygen Chandrabhaga, Konark, Odisha. method was followed in order to assess the of primary productivity of Bay of Bengal at Chandravaga, Konark, Odisha, Seasonally, the maximum Gross Primary Production and Net II. MATERIAL AND METHODS Primary Production were recorded in summer due to clear The water samples were collected from 50 cm. depth from weather and high atmospheric temperature and minimum during the sea-shore and analyzed for primary productivity. The study Monsoon season due to cloudy weather . On the other hand, was conducted for the year that is 2013-14. Different techniques Community respiration was found to be higher during summer have been used by different workers viz. Radioactive Carbon season and lower during winter season. (C14) (Slumann-Nielson, 1952), Chlorophyll method (Ryther and Yentsch, 1957) and oxygen method by light and dark bottle Index Terms- Primary production, gross primary production, net (Gaarder and Gran, 1927, Vollenweiden, 1969) for estimation of primary production, Community Respiration, Bay of Bengal and primary productivity. -

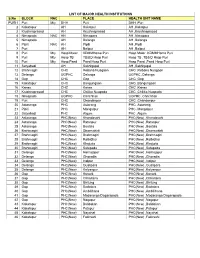

LIST of MAJOR HEALTH INSTITUTIONS S.No BLOCK NAC

LIST OF MAJOR HEALTH INSTITUTIONS S.No BLOCK NAC PLACE HEALTH UNIT NAME PURI1 Puri Mty DHH Puri DHH ,Puri 2 Kakatapur AH Kakatpur AH ,Kakatpur 3 Krushnaprasad AH Krushnaprasad AH ,Krushnaprasad 4 Nimapada NAC AH Nimapara AH ,Nimapara 5 Nimapada AH Balanga AH ,Balanga 6 Pipili NAC AH Pipili AH ,Pipili 7 Puri AH Baliput AH ,Baliput 8 Puri Mty Hosp Mater KDMMHome Puri Hosp Mater ,KDMMHome Puri 9 Puri Mty Hosp TB TB&ID Hosp Puri Hosp TB ,TB&ID Hosp Puri 10 Puri Mty Hosp Paed Paed Hosp Puri Hosp Paed ,Paed Hosp Puri 11 Satyabadi AH Sakhigopal AH ,Sakhigopal 12 Brahmagiri CHC Rebana Nuagaon CHC ,Rebana Nuagaon 13 Delanga UGPHC Delanga UGPHC ,Delanga 14 Gop CHC Gop CHC ,Gop 15 Kakatapur CHC Bangurigaon CHC ,Bangurigaon 16 Kanas CHC Kanas CHC ,Kanas 17 Krushnaprasad CHC Chilika Nuapada CHC ,Chilika Nuapada 18 Nimapada UGPHC Chrichhak UGPHC ,Chrichhak 19 Puri CHC Chandanpur CHC ,Chandanpur 20 Astaranga PHC Astarang PHC ,Astarang 21 Pipili PHC Mangalpur PHC ,Mangalpur 22 Satyabadi PHC Algum PHC ,Algum 23 Astaranga PHC(New) Khandasahi PHC(New) ,Khandasahi 24 Astaranga PHC(New) Ratanpur PHC(New) ,Ratanpur 25 Astaranga PHC(New) Bantala PHC(New) ,Bantala 26 Brahmagiri PHC(New) Dharmakirti PHC(New) ,Dharmakirti 27 Brahmagiri PHC(New) Brahmagiri PHC(New) ,Brahmagiri 28 Brahmagiri PHC(New) Raibidhar PHC(New) ,Raibidhar 29 Brahmagiri PHC(New) Khajuria PHC(New) ,Khajuria 30 Brahmagiri PHC(New) Satapada PHC(New) ,Satapada 31 Delanga PHC(New) Harirajapur PHC(New) ,Harirajapur 32 Delanga PHC(New) Ghoradia PHC(New) ,Ghoradia 33 Delanga PHC(New) Indipur PHC(New) -

Pipili As a Rural Tourism Destination

Orissa Review * January - 2008 Pipili as a Rural Tourism Destination Abhisek Mohanty Pipili, the heart of the colorful art work called in Pipili that the craft has a living and vibrant appliqué, is located at a distance of 20 km from tradition continuing over centuries. While most Bhubaneswar on the NH 203 connecting appliqué craftsmen are concentrated in Pipili, there Bhubaneswar with Puri. Pipili is located at 20.12° are quite a few in Puri and Khallikote, N 85.83° E. It is at Pipili that one takes a turn Parlakhemundi and Boudh. and moves eastward to proceed to Konark, the Appliqué works of Pipili is also known as site of the Sun Temple. At an average elevation patching cloth design. The local name of this of 25 metres (82 feet), Pipili is a Notified Area handicraft is Chandua. As with many other Council (NAC) and has 16 wards under handicrafts of Orissa, the roots of the applique jurisdiction of Puri district. It is famous for art/craft form is interwined with the rituals and designing beautiful appliqué handicrafts. As of traditions of Lord Jagannath, the presiding deity 2001 India Census, Pipili had a population of of the Puri temple. The appliqué items are mainly 14,263. Males constitute 51% of the population used during processions of the deities in their and females 49%. Pipili has an average literacy various ritual outings. Items like Chhati, Tarasa rate of 70%, higher than the national average of and Chandua are used for the purpose. However, 59.5%: male literacy is 77%, and female literacy the appliqué work in its colourful best is most is 63%. -

EXTRAORDINARY PUBLISHED by AUTHORITY No. 842, CUTTACK, SATURDAY, JUNE 2, 2018 / JAISTHA 12, 1940

EXTRAORDINARY PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 842, CUTTACK, SATURDAY, JUNE 2, 2018 / JAISTHA 12, 1940 HOUSING & URBAN DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT NOTIFICATION The 1st June, 2018 S.R.O. No. 194/2018— WHEREAS, the draft notification for the purpose of inclusion of additional 65 (sixty five) Revenue Villages in Puri Konark Development Authority Area declared as such in the Notification of the Government of Odisha in the Housing & Urban Development Department No.4777, dated the 14th February, 1997 was published as required by rule 3(1) of the Odisha Development Authorities Rules,1983 in the Extraordinary issue of the Odisha Gazette No.1938, dated the 17th November, 2017 under the Notification of the Government in the Housing & Urban Development Department No.26586, dated the 16th November, 2017 ; AND, WHEREAS, objections and suggestions received in respect of the said draft before the expiry on the date specified have been duly considered by the State Government; NOW, THEREFORE, in the exercise of powers conferred by sub-section (2) of Section 3 of the Odisha Development Authorities Act, 1982 and in partial modification to the Government of Odisha in the Housing & Urban Development Department Notification No. 4777, dated the 14th February, 1997, the State Government do hereby declare that the existing Puri Konark Development Area shall include the additional areas of the revenue villages as mentioned in Col. 2 of Schedule-I below and accordingly the boundaries of Puri Konark Development Area shall be described in Schedule-II below : 2 SCHEDULE-I Sl. Name of the Name of the Police Name of the Name of the Name of No. -

EXTRAORDINARY PUBLISHED by AUTHORITY No. 1938, CUTTACK, FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 17, 2017/KARTIKA 26, 1939

EXTRAORDINARY PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 1938, CUTTACK, FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 17, 2017/KARTIKA 26, 1939 HOUSING & URBAN DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT NOTIFICATION The 16th November, 2017 S.R.O. No. 567/2017.— In pursuance of rule 3 of the Odisha Development Authorities Rules, 1983, the State Govt. do hereby publish a proposal for inclusion of the areas mentioned in Column (2) of the schedule below in the “Puri Konark Development Authority Area” declared as such by the Notification of the Govt. of Odisha in the Housing & Urban Development Department No.4777/HUD., dated the 14th February,1997. Objections and suggestions, if any, may be filed in writing before the Deputy Secretary to Government, Housing & Urban Development Department, Odisha Secretariat, Bhubaneswar by any person in respect of the said proposal within 30(thirty) days from the date of publication of this Notification in the Odisha Gazette, which shall be considered by the State Govt. before taking a final decision: SCHEDULE Sl. Name of the Name of the Name of the Name of the Name of No. Revenue Police Station & Urban Local Tahasil Sub-register Mouza No. Bodies / Grampanchayat (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) 1 Gorual Puri 82 Gorual Brahmagiri Puri Sadar 2 Girola Puri 80 Gorual Brahmagiri Puri Sadar 3 Alipada Puri 81 Gorual Brahmagiri Puri Sadar 4 Sandhapur Puri 79 Gorual Brahmagiri Puri Sadar 5 Amangababati Puri 83 Gorual Brahmagiri Puri Sadar 2 (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) 6 Kasijagannathpur Puri 94 Samanga Brahmagiri Puri Sadar 7 Sadanandapur Satyabadi 123 Biraramachandr Satyabadi Satyabadi apur