Archived Content Information Archivée Dans Le

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

For Immediate Release SPH REIT Appoints Ng Yat Chung As Director

For Immediate Release SPH REIT appoints Ng Yat Chung as Director SINGAPORE, 31 July 2017 – SPH REIT Management Pte.Ltd. (“SPHRM”) has appointed Mr Ng Yat Chung (伍逸松) as a non-independent non-executive director to its Board with effect from 1 August 2017. Mr Ng will also be a member of the Nominating and Remuneration Committee. Mr Ng, 55, will replace Mr Alan Chan Heng Loon, 64, who is retiring from the board on the same day. The other directors are Dr Leong Horn Kee, Chairman, Mr Soon Tit Koon, Mr David Chia and Ms Rachel Eng, all of whom are independent directors, Mr Anthony Mallek and Ms Ginney Lim who are both non-independent non-executive directors. Mr Ng is also the Executive Director of Singapore Press Holdings Limited (“SPH”) and will succeed Mr Chan as SPH’s CEO from 1 September 2017. Mr Ng was Special Advisor of Neptune Orient Lines Ltd (NOL) from 9 June 2016 to 26 May 2017. Prior to that, he was NOL’s Group President & CEO from 1 October 2011. He also held several assignments with Temasek Holdings between 2007 and 2011. He was with the Singapore Armed Forces since 1980 and rose to the position of the Chief of Defence Force from July 2003 to April 2007. Mr Ng said: “SPH REIT has a good track record, with our properties enjoying full occupancy and strong partnership with our tenants. We are well positioned to continue delivering a trusted and successful brand in Singapore.” Dr Leong Horn Kee, Chairman of the SPHRM Board, said: "On behalf of the board, I would like to welcome Yat Chung, who will be a valuable asset to the team given his experience and expertise. -

Board of Directors

14. SPH REIT ANNUAL REPORT 2017 BOARD OF DIRECTORS Standing from left Anthony Mallek Yeo Hiap Seng Ltd. From 1984 to 1993, he David Chia Chay Poh LEONG Soon Tit Koon worked in the venture capital and merchant banking sector. From 1977 to 1983, he was Seated from left HORN KEE Alan Chan Heng Loon a deputy director at the Ministry of Finance Ginney Lim May Ling CHAIRMAN, NON-EXECUTIVE AND and Ministry of Trade & Industry. Dr Leong Leong Horn Kee INDEPENDENT DIRECTOR / MEMBER, was a Member of Parliament for 22 years Ng Yat Chung NOMINATING & REMUNERATION COMMITTEE Rachel Eng Yaag Ngee from 1984 to 2006. Dr Leong is the Chairman of CapitalCorp Dr Leong holds Bachelor degrees in Production Partners Private Limited, a corporate finance Engineering, Economics, and Chinese; advisory firm. He is currently Singapore’s Master of Business Administration from non-resident High Commissioner to Cyprus. INSEAD; Master of Business Research and From 1994 to 2008, Dr Leong was an executive Doctorate of Business Administration from director of Far East Organization, CEO of the University of Western Australia (UWA). Orchard Parade Holdings Ltd and CEO of INUNISON | INSYNC 15. Consultants Pte Ltd rising to the and SingHealth Fund, SGH Health SOON position of the Executive Director Development Fund Committee. TIT KOON of the company in 1996. From 1981 to 1987, he served as the District Ms Eng was awarded Law Firm NON-EXECUTIVE AND INDEPENDENT Valuer in the Property Tax Division Managing Partner of the Year at the DIRECTOR / CHAIRMAN, AUDIT & RISK of the Inland Revenue Authority of ALB South East Asia Law Awards COMMITTEE / MEMBER, NOMINATING & REMUNERATION COMMITTEE Singapore (IRAS). -

TOWARDS a KNOWLEDGE-BASED SAF

TOWARDS a KNOWLEDGE-BASED SAF MR NEO KIM HAI Head KM Office Singapore Armed Forces, Ministry of Defence One Objective Three Imperatives Five Initiatives One Objective Three Imperatives Five Initiatives One Objective – A Knowledge-based SAF Leadership Support Believe in Knowledge Capital Ground Understands Usefulness of KM One Objective Three Imperatives Five Initiatives Spectrum of Operations to contribute to Regional & International security International Peace Support Maritime Humanitarian Counter Piracy Operations Security Assistance & Disaster Relief One Objective Three Imperatives Five Initiatives Wide Spectrum of Operations to contribute to Local & Regional security Learn New Operational Knowledge Ops Knowledge Apply into Cycle Internalise Doctrines & Quickly Tactics One Objective Three Imperatives Five Initiatives Operational Complexity 3rd Generation SAF - More Networked & Integrated One Objective Three Imperatives Five Initiatives Operational Complexity Power of the Fighter Entire Network Attack Aircrafts Helicopter SHOOT Command Systems & Artillery Processes Integrated Network Sensors “ In the 3rd Generation SAF, the soldier not just fights with his rifle, he has got the whole SAF in his backpack”. - Mr Teo Chee Hean, Deputy Prime Minister/ Minister for Defence, Singapore One Objective Three Imperatives Five Initiatives Operational Complexity • War-fighters must be Air force Knowledge Hub conversant with Ops Doctrine & Info Flow • Draw Expertise from Centres of Knowledge Navy Knowledge Hub Army Knowledge Hub One Objective Three -

OPERATION FLYING EAGLE SAF Humanitarian Assistance After the Tsunami

REACHING OUT OPERATION FLYING EAGLE SAF Humanitarian Assistance after the Tsunami By courtesy of SPH – The New Paper. Photo by Mohd Ishak Samon. A Republic of Singapore Air Force C-130 Hercules transport plane from 122 Squadron warms up at Sultan Iskandar Muda Airport. The earthquake put the airport’s control tower out of action and aircrews had to keep a sharp lookout for other aircraft and helicopters that streamed in and out of the SNP • EDITIONS congested airport. Another hazard: civilians who crowded grassy areas fringing the airport’s flightline and taxiways, an imprint of hoping for a flight out of the ruined city. SNP•INTERNATIONAL REACHING OUT Operation Flying Eagle Foreword Contents 4 5 Foreword 06 Nature’s fury unleashed 08 The eagle stirs 24 Mission checklist 38 Moving into uncharted territory 54 Making a difference 78 Transition to recovery 98 Reflections and homecoming 114 Mission accomplished 128 RSS Endurance (207), RSS Endeavour (210) and RSS Persistence (209) off the coast of Meulaboh in western Sumatra on 18 January 2005. This photo captures a historic moment for the Navy as it marked the fi rst time all four Landing Ships Tank (LSTs) were deployed for operations outside Singapore. The fourth LST, RSS Resolution (208), was then in the Northern Arabian Gulf. REACHING OUT Operation Flying Eagle Foreword This book is dedicated to December 26, 2004 will be remembered by The SAF moved swiftly into action and launched Operation colleagues from the Home Team and many willing volunteers. people around the world for years to come. Flying Eagle. Standby teams were deployable within 24 hours, Their efforts helped restore the lives of the people of Meulaboh, the men and women in MINDEF The powerful earthquake and tsunamis which struck and teams which were specially assembled for the disaster Banda Aceh and Phuket. -

Board of Directors

Singapore Press Holdings Annual Report 2016 BOARD OF DIRECTORS Lee Boon Yang Chairman Non-Executive and Independent Director Boon Yang was appointed a Director of SPH on 1 October 2011. He is the Non-Executive Chairman of Keppel Corporation Limited. He is also Chairman of Singapore Press Holdings Foundation Limited, Keppel Care Foundation Limited, Jilin Food Zone Pte Ltd and Jilin Food Zone Investment Holdings Pte Ltd. He has extensive experience in public service. He served as Member of Parliament for Jalan Besar and Jalan Besar Group Representation Constituency 01 (GRC) from December 1984 to April 2011. He was the Minister for Information, Communications and the Arts before retiring from political office in March 2009. From 1991 to 2003, he served as Minister in the Prime Minister’s Office, Minister for Defence, Minister for Labour and later Minister for Manpower. Prior to that, he held several public appointments including Senior Minister of State for Defence, National Development and Home Affairs, and Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministers for Environment, Finance, Home Affairs, and Communications and Information. Before entry into politics, he worked as a veterinarian and R&D Officer in the Primary Production Department. 02 He has also worked as the Assistant Regional Director for the US Feed Grains Council, and as Senior Project Manager for the Primary Industries Enterprise Pte Ltd. Boon Yang holds a B.V.Sc Hon (2A) from the University of Queensland. Alan Chan Heng Loon Chief Executive Officer Executive and Non-Independent Director Alan joined SPH as its Group President on 1 July 2002, and was appointed Chief Executive Officer on 1 January 2003. -

PSC Annual Report 2010

11 12 10 11 12 10 1 9 11 12 100 1 9 11 12 9 10 9 1 2 12 2 1 2 8 2 8 8 3 7 4 3 5 3 8 7 6 4 3 7 6 5 4 7 6 5 4 6 5 ANNUAL REPORT 2010 SINGAPORE PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION The Public Service Commission marks its 60th anniversary this year. Since its establishment, it has evolved and refined its roles and responsibilities, but its fundamental principles of integrity, impartiality and meritocracy remain unchanged. Themed Withstanding The Test Of Time, this year’s annual report pays tribute to PSC’s core values which have provided it with focus and gravitas as it goes about fulfilling its duties. Visual representations of time are used throughout this special edition annual report to echo its theme and celebrate the key milestones it has achieved over the years. CHAIRMAN’S REVIEW 2 MEMBERS OF THE PSC 4 - Present PSC Chairman & Members 5 - Past PSC Chairmen & Members 6 - Role of the Public Service Commission 9 PSC IN THE PAST 60 YEARS 10 - Key PSC milestones 12 - Service with distinction 22 - Going from strength to strength 25 - Beyond the call of duty 29 PSC SCHOLARSHIPS 2010 31 PSC SCHOLARSHIPS HOLDER 2010 35 - PSC Scholarships 2010 36 - The President’s Scholarship 37 - SAF Overseas Scholarship 38 - SPF Overseas Scholarship 39 - Overseas Merit Scholarship 40 - Local-Overseas Merit Scholarship 43 - Local Merit Scholarship (Medicine) ` 43 - Singapore Government Scholarship (Open) 44 - PSC Masters Scholarship 46 VISITS BY FOREIGN DELEGATES 47 - Summary of visits by foreign delegates 2001-2010 48 - Visits by foreign delegates 2010 50 APPOINTMENTS, PROMOTIONS, APPEALS AND 51 DISCIPLINARY CASES PSC SECRETARIAT 55 - Organisation Chart 56 CHAIRMAN’S REVIEW This year, the Public Service Commission (PSC) turns 60. -

Sph Reit Management Pte

Change - Announcement of Appointment::Appointment of Non-Executive Non-Indep... Page 1 of 3 Change - Announcement of Appointment::Appointment of Non-Executive Non-Independent Director Issuer & Securities Issuer/ Manager SPH REIT MANAGEMENT PTE. LTD. Securities SPH REIT - SG2G02994595 - SK6U Stapled Security No Announcement Details Announcement Title Change - Announcement of Appointment Date & Time of Broadcast 31-Jul-2017 18:31:30 Status New Announcement Sub Title Appointment of Non-Executive Non-Independent Director Announcement Reference SG170731OTHR6Y3G Submitted By (Co./ Ind. Name) Lim Wai Pun Designation Company Secretary Description (Please provide a detailed Appointment of Non-Executive Non-Independent Director description of the event in the box below) Additional Details Date Of Appointment 01/08/2017 Name Of Person Ng Yat Chung Age 55 Country Of Principal Residence Singapore The Board has considered the Nominating and Remuneration The Board's comments on this appointment Committee's assessment of Mr Ng Yat Chung's qualifications, (including rationale, selection criteria, and professional experience and its recommendations. The Board is satisfied the search and nomination process) that Mr Ng will be able to contribute significantly to SPH Reit Management Pte Ltd. Whether appointment is executive, and if so, Non-Executive Director the area of responsibility Job Title (e.g. Lead ID, AC Chairman, AC Nominating and Remuneration Committee Member Member etc.) Familial relationship with any director and/ or substantial shareholder of -

Rongxiang Lin Self-Employed Computer Engineer Received

Written Representation 5 Name: Rongxiang Lin Self-employed computer engineer Received: 17 Jan 2018 Title: Select Committee on Deliberate Online Falsehoods - Causes, Consequences and Countermeasures Dear Clerk of Parliament, I type in support of Minister K Shanmugam's speech in parliament and with reference to the Green Paper presented to Parliament on "Deliberate Online Falsehoods: Challenges and Implications" (Misc. 10 of 2018). In this voluntary contribution, I declare that I have absolutely no interest, in fact am utterly dispassionate about this subject matter, yet, am contributing within my abilities, limits and means. I am a trained and certified United Nations sustainable development framework specialist, and I have also served in the capacity of a top secret unit at HQ Mindef leading up to the War on Terror. I reported directly to Mr. Ng Yat Chung, who is now the Chief Executive of Singapore Press Holdings, as well as several key commanders such as Mr. Desmond Kuek as well as my then Commanding Officer Alvin Kek who is assisting Mr. Kuek at SMRT lately, several retired generals such as Mr. Lim Feng and Mr. Hugh Lim U Yang who is CEO Building and Construction Authority, and more poignantly also Mr. Ravinder Singh who was the first minority Chief of Army in Singapore. Mr. Lee Kuan Yew once said approximately, "Freedom of the press, freedom of the news media, must be subordinated to the overriding needs of the integrity of Singapore, and to the primacy of purpose of an elected government." I have never been a fan of press freedom and will never be. -

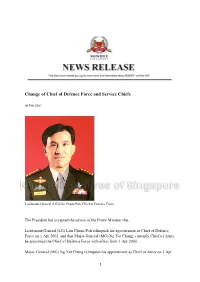

Change of Chief of Defence Force and Service Chiefs

Change of Chief of Defence Force and Service Chiefs 06 Feb 2003 Lieutenant-General (LG) Lim Chuan Poh, Chief of Defence Force. The President has accepted the advice of the Prime Minister that: Lieutenant-General (LG) Lim Chuan Poh relinquish his appointment as Chief of Defence Force on 1 Apr 2003, and that Major-General (MG) Ng Yat Chung, currently Chief of Army, be appointed the Chief of Defence Force with effect from 1 Apr 2003. Major-General (MG) Ng Yat Chung relinquish his appointment as Chief of Army on 1 Apr 1 2003, and that Brigadier-General (BG) Desmond Kuek Bak Chye, currently Director Joint Intelligence Directorate and concurrently Chief of Staff (General Staff), be appointed Chief of Army with effect from 1 Apr 2003, and Rear-Admiral (RADM) Lui Tuck Yew relinquish his appointment as Chief of Navy on 1 Apr 2003, and that Rear-Admiral (RADM) Ronnie Tay, currently Chief of Staff and concurrently Head Naval Operations Department, be appointed Chief of Navy with effect from 1 Apr 2003. The Prime Minister made these recommendations to the President following consultation with the Armed Forces Council. The changes are part of the continuing process of leadership renewal and to release talented SAF officers to serve in other positions in the public and private sectors. LG Lim Chuan Poh and RADM Lui Tuck Yew will both return to the Administrative Service after attending the Advanced Management Program at Harvard University. Since his enlistment in 1979, LG Lim Chuan Poh has served the SAF with distinction. He was awarded the SAF Overseas Scholarship in 1980. -

Mr Lim Chuan Poh Chairman, A*STAR Mr Lim Chuan Poh Was

Mr Lim Chuan Poh Chairman, A*STAR Mr Lim Chuan Poh was appointed Chairman A*STAR on 1 April 2007 to lead A*STAR in advancing science and developing innovative technology to further economic growth and improve lives. Appointed as Deputy Chairman A*STAR in November 2006, Mr Lim has been a Board Member of Nanyang Technological University (NTU) since 2003, and the National Research Foundation since January 2006. He was the Chairman of the National Infocomm Security Committee from 2010 to 2015 and co-chaired the National Cybersecurity R&D Executive Committee until April 2016. He is currently the Chairman of the Governing Board of the Lee Kong Chian School of Medicine, a joint Medical School between NTU and Imperial College. Currently, he also co-chairs the Health and Biomedical Sciences and the National Robotics Programme Steering Committee, and is a member of the Advanced Manufacturing and Engineering Executive Committee. Mr Lim was appointed as an Adjunct Professor at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy (LKY SPP) at the National University of Singapore (NUS) since July 2013. Internationally, Mr Lim is a Board and Council Member of the Science and Technology in Society (STS) forum; and a Member of Japan’s World Premier International (WPI) Initiative Programme Assessment and Review Committee since 2007; as well as being a Special Committee Member of the Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST) Advisory Committee since 2014. He became a founding member of Frost and Sullivan Board of Governors of the Economic Development Innovation Council in 2014. Prior to A*STAR, Mr Lim was Permanent Secretary at the Ministry of Education (MOE). -

Ministers, Permanent Secretaries, Chiefs of Defence Force

MINISTERS, PERMANENT SECRETARIES, CHIEFS OF DEFENCE FORCE 1965 1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 MINISTERS DEFENCE Dr Goh Keng Swee Lim Kim San Dr Goh Keng Swee Howe Yoon Chong Goh Chok Tong Dr Yeo Ning Hong 1965 - 1967* 1967 - 1970+ 1970 - 1979 1979 - 1982 1982 - 1991 1991 - 1994 Dr Lee Boon Yang 1994 - 1995 SECRETARIES PERMANENT G E Bogaars Pang Tee Pow Cheong Quee Wah Lim Siong Guan Eddie Teo 1965 - 1970 1970 - 1977 1977 - 1981 1981 - 1994 1994 - 2000 DEFENCE FORCE CHIEFS OF LG Winston Choo ‡ LG Winston Choo LG Ng Jui Ping Chief of General Staff 1990 - 1992 1992 - 1995 1976 - 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 2015 MINISTERS DEFENCE Dr Tony Tan Keng Yam Teo Chee Hean Dr Ng Eng Hen 1995 - 2003 2003 - 2011 2011 - SECRETARIES PERMANENT Peter Ho Chiang Chie Foo Chan Yeng Kit 2001 - 2004 2004 - 2013 2013 - DEFENCE FORCE CHIEFS OF LG Bey Soo Khiang LG Lim Chuan Poh LG Ng Yat Chung LG Desmond Kuek LG Neo Kian Hong LG Ng Chee Meng 1995 - 2000 2000 - 2003 2003 - 2007 2007 - 2010 2010 - 2013 2013 - * Dr Goh Keng Swee was Minister of Defence & Security (Aug 1965 - Sep 1965), and Minister of Interior & Defence (Sep 1965 - Aug 1967). ‡ The post of Chief of Defence Force was created in 1990. Before that, the senior officer commanding the SAF was known as the Director + Lim Kim San was Minister of Interior & Defence (Aug 1967 - Apr 1968), and Minister of Defence (Apr - Aug 1970). General Staff (DGS) (1966 - 1976), and the Chief of General Staff (1976 - 1990). The following served as DGS: Tan Teck Khim (1966 - 1968), COL Kirpa Ram Vij (Jun - Dec 1968), BG T J D Campbell (1968 - 1970), BG Kirpa Ram Vij (1970 - 1974), and LG Winston Choo (1974 - 1976). -

ภาษาอังกฤษแก ป ญหาเวลาไปต างประเทศ (Troubleshooting English

ภาษาอังกฤษแกปญหาเวลาไปตางประเทศ (Troubleshooting English When Going Abroad) กองการทูตฝายทหาร สํานักวิเทศสัมพันธ กรมขาวทหาร กองบัญชาการทหารสูงสุด กันยายน ๒๕๔๕ คํานํา คูมือภาษาอังกฤษแกปญหาเวลาไปตางประเทศเลมนี้ เปนความริเริ่มของกองการทูตฝายทหาร โดย ไดรับแรงบันดาลใจจาก พลโท อรพัฒน สุกไสว เจากรมขาวทหาร ที่ไดกรุณาดําริวา กองการทูตฝายทหาร เปน หนวยหลักในการดําเนินการเรื่องการเดินทางไปราชการตางประเทศของผูบังคับบัญชา อีกทั้งมีบุคลากรที่มี ประสบการณในการเดินทางไปตางประเทศทั้งในฐานะเปนเลขานุการคณะเดินทางและไปศึกษาตอตางประเทศ จึงนา ที่จะนําความรูและประสบการณทางดานการใชภาษาอังกฤษที่จําเปนตอการเดินทางไปตางประเทศมาถายทอดให ผูสนใจไดใชประโยชน ความมุงหมายของคูมือเลมนี้ เพื่อเปนแนวทางและเปนการชวยจําสําหรับแกปญหาเฉพาะหนาในการใช ภาษาอังกฤษ ใหกับผูที่เดินทางไปราชการตางประเทศ ดังนั้นคณะผูจัดทําจึงพยายามจับประเด็น และสรุปเฉพาะ เนื้อหาสาระที่สําคัญที่นาจะจําเปนตองใช โดยใหมีความสั้นกระชับ เพื่อใหไดรูปเลมกระทัดรัด เหมาะแกการพก ติดกระเปาและหยิบมาใชเมื่อจําเปน กองการทูตฝายทหาร และคณะผูจัดทํา หวังเปนอยางยิ่งวา คูมือ "ภาษาอังกฤษแกปญหาเวลาไป ตางประเทศ" เลมนี้ จะเปนประโยชนไมมากก็นอย และขอนอมรับคําติชม เพื่อปรับปรุงแกไขในโอกาสตอไป พันเอก กฤช กุวานนท ( กฤช กุวานนท ) ผูอํานวยการกองการทูตฝายทหาร สํานักวิเทศสัมพันธ กรมขาวทหาร กันยายน ๒๕๔๕ สารบัญ • คํากลาว (Speech) หลักเกณฑโดยทั่วไปในการกลาวสุนทรพจน 3 ตัวอยางการกลาวสุนทรพจนในโอกาสไปเยือนตางประเทศ 4 ตัวอยางคํากลาวตอนรับแขกตางประเทศมาเยือนประเทศไทย 5 ตัวอยางคํากลาวการเดินทางไปแนะนําตนเองแกผูนําตางประเทศ 8 ตัวอยางคํากลาวขอบคุณในโอกาสเยือนสถานที่ตางๆ 12 ตัวอยางคํากลาวแสดงความยินดีแกผูที่ไดรับเครื่องราชอิสริยาภรณไทย 15 ตัวอยางคํากลาวขอบคุณการไดรับเครื่องอิสริยาภรณจากตางประเทศ