Aristocracy of Armed Talent

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

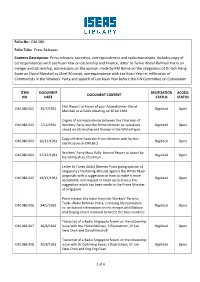

Folio No: DM.086 Folio Title: Press Releases Content Description: Press Releases, Speeches, Correspondences and Radio Transcripts

Folio No: DM.086 Folio Title: Press Releases Content Description: Press releases, speeches, correspondences and radio transcripts. Includes copy of correspondences with Lee Kuan Yew on citizenship and finance, letter to Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra on merger and citizenship, submissions on the opinion made by KM Byrne on the allegations of Dr Goh Keng Swee on David Marshall as Chief Minister, correspondence with Lee Kuan Yew re: infiltration of Communists in the Workers' Party and speech of Lee Kuan Yew before the UN Committee on Colonialism ITEM DOCUMENT DIGITIZATION ACCESS DOCUMENT CONTENT NO DATE STATUS STATUS First Report to Anson of your Assemblyman David DM.086.001 30/7/1961 Digitized Open Marshall at a Public Meeting on 30 Jul 1961 Copies of correspondence between the Chairman of DM.086.002 7/12/1961 Workers' Party and the Prime Minister re: questions Digitized Open raised on citizenship and finance in the White Paper Copy of letter from the Prime Minister with further DM.086.003 16/12/1961 Digitized Open clarification on DM.86.2 Workers' Party Mass Rally: Second Report to Anson by DM.086.004 17/12/1961 Digitized Open David Marshall, Chairman Letter to Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra giving opinion of Singapore's hardening attitude against the White Paper proposals with a suggestion on how to make it more DM.086.005 19/12/1961 Digitized Open acceptable, and request to meet up to discuss this suggestion which has been made to the Prime Minister of Singapore Press release of a letter from the Workers' Party to Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra, enclosing -

Mr Lim Neo Chian to Succeed Mr Koh Soo Keong As Chairman of Agri-Food and Veterinary Authority

MR LIM NEO CHIAN TO SUCCEED MR KOH SOO KEONG AS CHAIRMAN OF AGRI-FOOD AND VETERINARY AUTHORITY 1. With effect from 1 April 2016, Mr Lim Neo Chian will be appointed Chairman of the Agri-Food and Veterinary Authority (AVA) Board for a two-year term. Mr Lim is currently Deputy Chairman of the Board. 2. Mr Lim, who is Chairman of Ascendas Hospitality Trust Management Pte Ltd and Deputy Chairman of Gardens by the Bay Company Ltd, brings to AVA invaluable experience from his career in the military, public and private sectors. He previously headed the Singapore Tourism Board, ST Engineering, and JTC Corporation. He was also the Chief of Army from 1992 to 1995. 3. Mr Lim succeeds Mr Koh Soo Keong, who has served on the AVA Board for fourteen years. Mr Koh, who is Managing Director of EcoSave Pte Ltd, was AVA Chairman from 1st April 2008 – 31st March 2016. He was also an AVA Board Member from 2000-2004, and Deputy Chairman from 2006-2008. 4. Mr Koh helped AVA grow as an organisation, to better address its varied responsibilities in safe food supply, animal and plant health, animal welfare and management, and agri-trade facilitation. Under Mr Koh’s guidance, AVA strengthened food security for Singapore, including raising local farm productivity and ramping-up agricultural R&D and innovation. He also spurred AVA to embrace private sector partnerships, and a robust risk management- and science-based approach to grow and diversify our overseas food sources while upholding food safety standards. 5. Mr Koh strongly believes in engaging stakeholders and the community. -

Press R Elease

PRESS RELEASE NEW APPOINTMENTS TO THE BOARDS OF SPRING, JTC and EMA The Minister for Trade and Industry has appointed new members to the Boards of SPRING Singapore (SPRING), JTC Corporation (JTC) and Energy Market Authority (EMA). In addition, there were re-appointments at SPRING, EMA and Sentosa Development Corporation (SDC). These appointments took effect on 1 April 2010. SPRING Board 2. New Appointments Mr Roger Chia – Founder, Chairman and Managing Director, Rotary Engineering Limited COL Lai Chung Han – Director (Policy), Ministry of Defence Mr Viswa Sadasivan – Chief Executive Officer, Strategic Moves Pte Ltd Mr Tan Choon Shian – Deputy Managing Director, Economic Development Board Re-appointments Ms Chong Siak Ching – President and Chief Executive Officer, Ascendas Pte Ltd Mr Thomas Chua – Chairman and Managing Director, Teckwah Industrial Corporation Ltd Mr Lim Boon Wee – Deputy Secretary (Land and Corporate), Ministry of Transport Ms Janet Young – Managing Director, Regional Head MNC Asia, Bank of America (Singapore) 100 High Street, #09-01, The Treasury, Singapore 179434 T (65) 6225 9911 F (65) 6332 7260 www.mti.gov.sg PRESS RELEASE 3. Five members have stepped down from the SPRING Board: BG Ng Chee Meng – Chief of Air Force, Republic of Singapore Air Force Mr Manohar Khiatani – Chief Executive Officer, JTC Corporation Dr Jitendra Singh – Saul P Steinberg Professor of Management, The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania Mr Robert Tsao – Chairman Emeritus, United Microelectronics Corporation Mr Zagy Mohamad – Sales Director, Datacraft Singapore JTC Board 4. New Appointments Major- General Neo Kian Hong – Chief of Defence Force, Ministry of Defence Mr Ong Ye Kung – Assistant Secretary-General, National Trades Union Congress 5. -

New Zealand Defence Minister Calls on Dr Tan

New Zealand Defence Minister Calls on Dr Tan 30 Sep 1998 The New Zealand Minister for Defence, the Honourable Mr Max Bradford, called on the Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Defence, Dr Tony Tan, this morning, 30 Sep 98, at the Ministry of Defence, Gombak Drive. Upon his arrival at MINDEF, Mr Bradford reviewed a Guard-of-Honour. Mr Bradford is here on his introductory visit from 29 Sep to 2 Oct 98. Mr Bradford will call on Acting Prime Minister BG (NS) Lee Hsien Loong, and deliver the second lecture in the Institute of Defence and Strategic Studies (IDSS) "Strategic Challenges of the Asia Pacific" lecture series on 2 Oct 98. On the same day, Mr Bradford will visit the inaugural Ex SINGKIWI, a bilateral exercise between the Republic of Singapore Air Force (RSAF) and the Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF), at Paya Lebar Air Base (PLAB). RNZAF A-4K Skyhawks, and RSAF F-5 Tiger, F-16 Fighting Falcon and A-4SU Super Skyhawk fighter aircraft are conducting a range of air training activities under the exercise from 21 Sep to 2 Oct 98. Whilst at PLAB, he will also be shown the RSAF's Air Combat Manoeuvring Instrumentation (ACMI) system. Mr Bradford's programme includes visits to SAFTI Military Institute, Tuas Naval Base, Headquarters Artillery, Tengah Air Base, and Changi Air Base for the annual Maritime Patrol Aircraft (MPA) Training Affiliation between the RNZAF's P-3K squadron and the RSAF's Fokker 50 squadron. Singapore and New Zealand have a long-standing defence relationship, and this has strengthened significantly in recent years. -

HENG HARDWARE ENGINEERING PTE LTD LISTS of PROJECTS USING HENG LIGHTNING PROTECTION SYSTEM Project Type: Airbase

HENG HARDWARE ENGINEERING PTE LTD LISTS OF PROJECTS USING HENG LIGHTNING PROTECTION SYSTEM Project Type: Airbase S/N PROJECT 1 600 WEST CAMP ROAD (SELETAR AEROSPACE) 2 A&A WORK TO 14NOS GATEWAY @ TERMINAL 2 3 AIR TRAFFIC CONTROL CENTRE AT BIGGN HILL ROAD 4 AIRCRAFT BLAST FENCE FOR CHANGI AIRPORT TERMINAL 3 5 AIRCRAFT HANGAR 6 & 7 6 AIRLINE HOUSE AT CHANGI 7 AIRMAIL TRANSIT CENTRE AT CHANGI AIRCARGO COMPLEX 8 BLK 113E SEMBAWANG AIRBASE 9 BUDGET TERMINAL 10 CAB WEST L3 11 CAFHI CHANGI AIRPORT 12 CARGO T4 13 CHANGI AIRBASE 14 CHANGI AIRPORT 2ND SOUTH CROSS TAXIWAY 15 CHANGI AIRPORT AT BUDGET TERMINAL 16 CHANGI AIRPORT LIGHTING SHELTE 17 CHANGI AIRPORT TERMINAL 1 18 CHANGI AIRPORT TERMINAL 1 COACH STAND 19 CHANGI AIRPORT TERMINAL 2 20 CHANGI AIRPORT TERMINAL 2 FIXED GATEWAY 21 CHANGI AIRPORT TERMINAL 3 22 CHANGI AIRPORT TERMINAL PHASE 2 23 CHANGI AIRPORT VIP COMPLEX 24 CHANGI CUSTOM CHECKPOINT 25 CHANGI EAST AIRBASE 26 CHANGI EAST RUNWAY 3 27 CHANGI T2 FIXED GANGWAY 28 HANGAR 800 29 INTAIL AEROSPACE AT 32 LOYANG DRIVE 30 NOSE SHELTER AT SIA 31 PAYA LEBAR AIR BASE 32 PAYA LEBAR AIR BASE (JET FUEL STATION 2) 33 PROPOSED ERECTION OF AIRCRAFT HANGER 6 AT 540 AIRPORT ROAD 34 SELETAR AEROSPACE 35 SELETAR AIRBASE 36 SELETAR AIRPORT SOUTH POINT 37 SELETAR CONTROLA TOWER @ SELETAR AIRBASE NO.7 YISHUN INDUSTRIAL STREET 1, #01-48 NORTH SPRING BIZHUB, S(768162) TEL:68464111 FAX:68464222 Web:www.heng.com.sg Email:[email protected] HENG HARDWARE ENGINEERING PTE LTD LISTS OF PROJECTS USING HENG LIGHTNING PROTECTION SYSTEM Project Type: Airbase 38 SELETAR -

Report of the Ministerial Committee on 38 Oxley Road

REPORT OF THE MINISTERIAL COMMITTEE ON 38 OXLEY ROAD TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1: Background Chapter 2: Historical and heritage significance Chapter 3: Mr Lee Kuan Yew’s thinking and wishes on the property Chapter 4: Possible options for the property Chapter 5: Committee’s views 2 CHAPTER 1: BACKGROUND 1. Founding Prime Minister Mr Lee Kuan Yew’s former home at 38 Oxley Road (henceforth referred to as the “Property”) is a single-storey bungalow surrounded by low-rise residential developments. 2. The issue of whether to preserve Mr Lee’s home after his passing, to demolish it, or some other option has become a matter of public interest. Shortly after Mr Lee’s passing on 23 March 2015, PM Lee Hsien Loong addressed this issue in Parliament on 13 April 2015, where he said that “there is no immediate issue of demolition of the house, and no need for the Government to make any decision now”, given that Dr Lee Wei Ling “intended to continue living in the Property”. He also stated that “if and when Dr Lee Wei Ling no longer lives in the House, Mr Lee has stated his wishes as to what then should be done…however, it will be up to the Government of the day to consider the matter”. 3. Though there is no immediate need for a decision, given the significant public interest in the Property, the Cabinet 1 approved setting up a Ministerial Committee (“Committee”) on 1 June 2016 to consider the various options. The Committee was asked to prepare drawer plans of various options and their implications, with the benefit of views of those who had directly discussed the matter with Mr Lee, so that a future Government can refer to these plans and make a considered and informed decision when the time came to decide on the matter. -

TOWARDS a KNOWLEDGE-BASED SAF

TOWARDS a KNOWLEDGE-BASED SAF MR NEO KIM HAI Head KM Office Singapore Armed Forces, Ministry of Defence One Objective Three Imperatives Five Initiatives One Objective Three Imperatives Five Initiatives One Objective – A Knowledge-based SAF Leadership Support Believe in Knowledge Capital Ground Understands Usefulness of KM One Objective Three Imperatives Five Initiatives Spectrum of Operations to contribute to Regional & International security International Peace Support Maritime Humanitarian Counter Piracy Operations Security Assistance & Disaster Relief One Objective Three Imperatives Five Initiatives Wide Spectrum of Operations to contribute to Local & Regional security Learn New Operational Knowledge Ops Knowledge Apply into Cycle Internalise Doctrines & Quickly Tactics One Objective Three Imperatives Five Initiatives Operational Complexity 3rd Generation SAF - More Networked & Integrated One Objective Three Imperatives Five Initiatives Operational Complexity Power of the Fighter Entire Network Attack Aircrafts Helicopter SHOOT Command Systems & Artillery Processes Integrated Network Sensors “ In the 3rd Generation SAF, the soldier not just fights with his rifle, he has got the whole SAF in his backpack”. - Mr Teo Chee Hean, Deputy Prime Minister/ Minister for Defence, Singapore One Objective Three Imperatives Five Initiatives Operational Complexity • War-fighters must be Air force Knowledge Hub conversant with Ops Doctrine & Info Flow • Draw Expertise from Centres of Knowledge Navy Knowledge Hub Army Knowledge Hub One Objective Three -

Change in Chief of Navy

Change in Chief of Navy 02 Jul 2014 Outgoing Chief of Navy Rear-Admiral Ng Chee Peng (left) and Incoming Chief of Navy Read-Admiral Lai Chung Han (right). Rear-Admiral (RADM) Lai Chung Han, currently Deputy Secretary (Policy) at the Ministry of Defence (MINDEF), will take over from RADM Ng Chee Peng as Chief of Navy on 1 August 2014. This change is part of the continuing process of leadership renewal in the Singapore Armed Forces (SAF). Since joining the SAF in 1988, RADM Ng Chee Peng, 44, has served the SAF with distinction. Through the course of his career, RADM Ng has held, amongst others, the appointments of Commanding Officer of RSS Victory; Commanding Officer of 188 Squadron; Commander of 1st Flotilla; Director (Policy); Fleet Commander; Chief of Staff-Naval Staff; and Chief of Staff-Joint Staff. RADM Ng has held the post of Chief of Navy since 29 Mar 2011. As Chief of Navy, RADM Ng has maintained the Republic of Singapore Navy's (RSN) high state of operational readiness by leading it through the successful conduct of local and overseas maritime operations. He laid the foundations for the RSN's future capabilities byoperationalisingnew platforms such as the ARCHER- class submarines and reorganizing the RSN's operational, training and safety systems. He also introduced various initiatives to better engage RSN servicemen and to further strengthen their commitment to defence. He also initiated efforts by the RSN, e.g. Navy@VIVO, to reach out to the public and the wider community. Under RADM Ng's leadership, the RSN has made valuable contributions to international counter-piracy efforts and played a key role through its command of Combined Task Force 151 in the Gulf of Aden. -

OPERATION FLYING EAGLE SAF Humanitarian Assistance After the Tsunami

REACHING OUT OPERATION FLYING EAGLE SAF Humanitarian Assistance after the Tsunami By courtesy of SPH – The New Paper. Photo by Mohd Ishak Samon. A Republic of Singapore Air Force C-130 Hercules transport plane from 122 Squadron warms up at Sultan Iskandar Muda Airport. The earthquake put the airport’s control tower out of action and aircrews had to keep a sharp lookout for other aircraft and helicopters that streamed in and out of the SNP • EDITIONS congested airport. Another hazard: civilians who crowded grassy areas fringing the airport’s flightline and taxiways, an imprint of hoping for a flight out of the ruined city. SNP•INTERNATIONAL REACHING OUT Operation Flying Eagle Foreword Contents 4 5 Foreword 06 Nature’s fury unleashed 08 The eagle stirs 24 Mission checklist 38 Moving into uncharted territory 54 Making a difference 78 Transition to recovery 98 Reflections and homecoming 114 Mission accomplished 128 RSS Endurance (207), RSS Endeavour (210) and RSS Persistence (209) off the coast of Meulaboh in western Sumatra on 18 January 2005. This photo captures a historic moment for the Navy as it marked the fi rst time all four Landing Ships Tank (LSTs) were deployed for operations outside Singapore. The fourth LST, RSS Resolution (208), was then in the Northern Arabian Gulf. REACHING OUT Operation Flying Eagle Foreword This book is dedicated to December 26, 2004 will be remembered by The SAF moved swiftly into action and launched Operation colleagues from the Home Team and many willing volunteers. people around the world for years to come. Flying Eagle. Standby teams were deployable within 24 hours, Their efforts helped restore the lives of the people of Meulaboh, the men and women in MINDEF The powerful earthquake and tsunamis which struck and teams which were specially assembled for the disaster Banda Aceh and Phuket. -

Archived Content Information Archivée Dans Le

Archived Content Information identified as archived on the Web is for reference, research or record-keeping purposes. It has not been altered or updated after the date of archiving. Web pages that are archived on the Web are not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards. As per the Communications Policy of the Government of Canada, you can request alternate formats on the "Contact Us" page. Information archivée dans le Web Information archivée dans le Web à des fins de consultation, de recherche ou de tenue de documents. Cette dernière n’a aucunement été modifiée ni mise à jour depuis sa date de mise en archive. Les pages archivées dans le Web ne sont pas assujetties aux normes qui s’appliquent aux sites Web du gouvernement du Canada. Conformément à la Politique de communication du gouvernement du Canada, vous pouvez demander de recevoir cette information dans tout autre format de rechange à la page « Contactez-nous ». CANADIAN FORCES COLLEGE / COLLÈGE DES FORCES CANADIENNES AMSC 6 / CSEM 6 Warfare in the 21st Century MYTH OR REALITY : NETWORK-CENTRIC WARARE AND INTEGRATED COMMAND AND CONTROL IN THE INFORMATION AGE? By / par LTC Seng Hock Lim Singapore Armed Forces October 2003 This paper was written by a student La présente étude a été rédigée par un attending the Canadian Forces College in stagiaire du Collège des Forces fulfillment of one of the requirements of the canadiennes pour satisfaire à l'une des Course of Studies. The paper is a scholastic exigences du cours. L'étude est un document, and thus contains facts and document qui se rapporte au cours et opinions, which the author alone considered contient donc des faits et des opinions que appropriate and correct for the subject. -

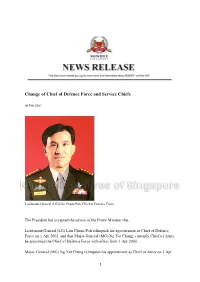

Change of Chief of Defence Force and Service Chiefs

Change of Chief of Defence Force and Service Chiefs 06 Feb 2003 Lieutenant-General (LG) Lim Chuan Poh, Chief of Defence Force. The President has accepted the advice of the Prime Minister that: Lieutenant-General (LG) Lim Chuan Poh relinquish his appointment as Chief of Defence Force on 1 Apr 2003, and that Major-General (MG) Ng Yat Chung, currently Chief of Army, be appointed the Chief of Defence Force with effect from 1 Apr 2003. Major-General (MG) Ng Yat Chung relinquish his appointment as Chief of Army on 1 Apr 1 2003, and that Brigadier-General (BG) Desmond Kuek Bak Chye, currently Director Joint Intelligence Directorate and concurrently Chief of Staff (General Staff), be appointed Chief of Army with effect from 1 Apr 2003, and Rear-Admiral (RADM) Lui Tuck Yew relinquish his appointment as Chief of Navy on 1 Apr 2003, and that Rear-Admiral (RADM) Ronnie Tay, currently Chief of Staff and concurrently Head Naval Operations Department, be appointed Chief of Navy with effect from 1 Apr 2003. The Prime Minister made these recommendations to the President following consultation with the Armed Forces Council. The changes are part of the continuing process of leadership renewal and to release talented SAF officers to serve in other positions in the public and private sectors. LG Lim Chuan Poh and RADM Lui Tuck Yew will both return to the Administrative Service after attending the Advanced Management Program at Harvard University. Since his enlistment in 1979, LG Lim Chuan Poh has served the SAF with distinction. He was awarded the SAF Overseas Scholarship in 1980. -

A Maritime Force for a Maritime Nation

A MARITIME FORCE FOR A MARITIME NATION THE REPUBLIC OF SINGAPORE NAVY’S GOLDEN JUBILEE THE REPUBLIC OF SINGAPORE NAVY’S POINTER Monograph No. 12 POINTER Monograph POINTER MONOGRAPH NO. 12 RSN50 DĂƌŝƟŵĞ&ŽƌĐĞ&ŽƌDĂƌŝƟŵĞEĂƟŽŶ POINTER MONOGRAPH NO. 12 REPUBLIC OF SINGAPORE NAVY 50th Anniversary 1967 ~ 2017 A WƵďůŝĐĂƟ ŽŶ ŽĨ ƚŚĞ ^ŝŶŐĂƉŽƌĞ AƌŵĞĚ &ŽƌĐĞƐ EDITORIAL BOARD Advisor BG Chua Boon Keat Chairman COL Simon Lee Wee Chek Deputy Chairman COL(NS) Irvin Lim Members COL(NS) Tan Swee Bock COL(NS) Benedict Ang Kheng Leong COL Victor Huang COL Kevin Goh COL Goh Tiong Cheng ME6 Jason Lim MAJ(NS) Charles Phua Chao Rong MS Melissa Ong MR Josiah Liang MR Kuldip Singh MR Daryl Lee Chin Siong MS Sonya Chan CWO Ng Siak Ping MR Eddie Lim EDITORIAL TEAM Editor MS Helen Cheng Assistant Editor MR Bille Tan Research Specialists REC David Omar Ting REC Koo Yi Xian Published by POINTER: Journal of the Singapore Armed Forces ^&d/DŝůŝƚĂƌLJ/ŶƐƟƚƵƚĞ 500 Upper Jurong Road Singapore 638364 ǁǁǁ͘ŵŝŶĚĞĨ͘ŐŽǀ͘ƐŐͬƐĂŌŝͬƉŽŝŶƚĞƌ First published in 2017 Copyright © 2017 by the Government of the Republic of Singapore. ISBN 978-981-11-3301-5 ůůƌŝŐŚƚƐƌĞƐĞƌǀĞĚ͘EŽƉĂƌƚŽĨƚŚŝƐƉƵďůŝĐĂƟŽŶŵĂLJďĞƌĞƉƌŽĚƵĐĞĚ͕ƐƚŽƌĞĚŝŶĂƌĞƚƌŝĞǀĂůƐLJƐƚĞŵ͕Žƌ ƚƌĂŶƐŵŝƩĞĚŝŶĂŶLJĨŽƌŵŽƌďLJĂŶLJŵĞĂŶƐ͕ĞůĞĐƚƌŽŶŝĐ͕ŵĞĐŚĂŶŝĐĂů͕ƉŚŽƚŽĐŽƉLJŝŶŐ͕ƌĞĐŽƌĚŝŶŐŽƌŽƚŚĞƌǁŝƐĞ͕ ǁŝƚŚŽƵƚƚŚĞƉƌŝŽƌǁƌŝƩĞŶƉĞƌŵŝƐƐŝŽŶŽĨƚŚĞDŝŶŝƐƚƌLJŽĨĞĨĞŶĐĞ͘ Disclaimer: dŚĞŽƉŝŶŝŽŶƐĂŶĚǀŝĞǁƐĞdžƉƌĞƐƐĞĚŝŶƚŚŝƐǁŽƌŬĂƌĞƚŚĞĂƵƚŚŽƌƐ͛ĂŶĚĚŽŶŽƚŶĞĐĞƐƐĂƌŝůLJƌĞŇĞĐƚƚŚĞŽĸĐŝĂů views of the Ministry of Defence. CONTENTS iv Foreword by Chief of Navy WĂƌƚ/͗dŚĞZ^E͕^ĂĨĞŐƵĂƌĚŝŶŐKƵƌDĂƌŝƟŵĞEĂƟŽŶ ϭ ^iŶŐaƉore͗