Translational Research in Bipolar Disorder

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Week 3 Emotional Regulation

WEEK 3 EMOTIONAL REGULATION GOALS/OBJECTIVES: This optional treatment module contains information to allow the participants to better understand how their TBI is related to their emotional dysregulation. This module should be utilized if several participants have expressed issues with mood swings, or if collateral information suggests client issues with emotional dysregulation. Emotional dysregulation refers to the inability of a person to control or regulate their emotional responses to provocative stimuli. The primary goals of this week will be for participants to: ❑ Identify what occurs during their mood swings ❑ Better understand their emotional responses to various situations ❑ Allow participants to practice coping skills to reduce or navigate emotional outbursts ❑ Provide psycho-education on how emotional dysregulation is related to TBI, and facilitate discussion during group about coping with emotional dysregulation. T I M E : Allow 1.5 hours for the session. NUMBER OF PARTICIPANTS: A minimum of four participants is recommended. © MINDSOURCE – Brain Injury Network 2018 WEEK 3 44 WEEK 3 PREPARATION VIDEO Watch the following video: https://youtu.be/Y02clqBzrbs For trainer info on emotional dysregulation and TBI, see: https://tinyurl.com/ahead-trainerinfo PRINT HANDOUTS ❑ Brain Injury and Emotion Regulation ❑ Mood Log ❑ Take Home Impressions These handouts can be found in the handout section for this week, the facilitator’s guide will indicate when these should be referenced. WRITE Write the following group rules on the white board for reference for participants throughout the treatment group: • Confidentiality: The information we discuss in this group is private, and members are expected to keep it that way. • Respect: Give your attention and consideration to participants, and they will do the same for you. -

G Protein-Coupled Receptors

S.P.H. Alexander et al. The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2015/16: G protein-coupled receptors. British Journal of Pharmacology (2015) 172, 5744–5869 THE CONCISE GUIDE TO PHARMACOLOGY 2015/16: G protein-coupled receptors Stephen PH Alexander1, Anthony P Davenport2, Eamonn Kelly3, Neil Marrion3, John A Peters4, Helen E Benson5, Elena Faccenda5, Adam J Pawson5, Joanna L Sharman5, Christopher Southan5, Jamie A Davies5 and CGTP Collaborators 1School of Biomedical Sciences, University of Nottingham Medical School, Nottingham, NG7 2UH, UK, 2Clinical Pharmacology Unit, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, CB2 0QQ, UK, 3School of Physiology and Pharmacology, University of Bristol, Bristol, BS8 1TD, UK, 4Neuroscience Division, Medical Education Institute, Ninewells Hospital and Medical School, University of Dundee, Dundee, DD1 9SY, UK, 5Centre for Integrative Physiology, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, EH8 9XD, UK Abstract The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2015/16 provides concise overviews of the key properties of over 1750 human drug targets with their pharmacology, plus links to an open access knowledgebase of drug targets and their ligands (www.guidetopharmacology.org), which provides more detailed views of target and ligand properties. The full contents can be found at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/ 10.1111/bph.13348/full. G protein-coupled receptors are one of the eight major pharmacological targets into which the Guide is divided, with the others being: ligand-gated ion channels, voltage-gated ion channels, other ion channels, nuclear hormone receptors, catalytic receptors, enzymes and transporters. These are presented with nomenclature guidance and summary information on the best available pharmacological tools, alongside key references and suggestions for further reading. -

Multi-Functionality of Proteins Involved in GPCR and G Protein Signaling: Making Sense of Structure–Function Continuum with In

Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences (2019) 76:4461–4492 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-019-03276-1 Cellular andMolecular Life Sciences REVIEW Multi‑functionality of proteins involved in GPCR and G protein signaling: making sense of structure–function continuum with intrinsic disorder‑based proteoforms Alexander V. Fonin1 · April L. Darling2 · Irina M. Kuznetsova1 · Konstantin K. Turoverov1,3 · Vladimir N. Uversky2,4 Received: 5 August 2019 / Revised: 5 August 2019 / Accepted: 12 August 2019 / Published online: 19 August 2019 © Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2019 Abstract GPCR–G protein signaling system recognizes a multitude of extracellular ligands and triggers a variety of intracellular signal- ing cascades in response. In humans, this system includes more than 800 various GPCRs and a large set of heterotrimeric G proteins. Complexity of this system goes far beyond a multitude of pair-wise ligand–GPCR and GPCR–G protein interactions. In fact, one GPCR can recognize more than one extracellular signal and interact with more than one G protein. Furthermore, one ligand can activate more than one GPCR, and multiple GPCRs can couple to the same G protein. This defnes an intricate multifunctionality of this important signaling system. Here, we show that the multifunctionality of GPCR–G protein system represents an illustrative example of the protein structure–function continuum, where structures of the involved proteins represent a complex mosaic of diferently folded regions (foldons, non-foldons, unfoldons, semi-foldons, and inducible foldons). The functionality of resulting highly dynamic conformational ensembles is fne-tuned by various post-translational modifcations and alternative splicing, and such ensembles can undergo dramatic changes at interaction with their specifc partners. -

Understanding the Genetics and Neurobiological Pathways Behind Addiction (Review)

EXPERIMENTAL AND THERAPEUTIC MEDICINE 21: 544, 2021 Understanding the genetics and neurobiological pathways behind addiction (Review) ALEXANDRA POPESCU1, MARIA MARIAN1*, ANA MIRUNA DRĂGOI1* and RADU‑VIRGIL COSTEA2* 1Department of Psychiatry, ‘Prof. Dr. Alex. Obregia’ Clinical Hospital of Psychiatry, 041914 Bucharest; 2Department of General Surgery, ‘Carol Davila’ University of Medicine and Pharmacy, 020021 Bucharest, Romania Received January 15, 2021; Accepted February 15, 2021 DOI: 10.3892/etm.2021.9976 Abstract. The hypothesis issued by modern medicine states 1. Introduction that many diseases known to humans are genetically deter‑ mined, influenced or not by environmental factors, which is Substance‑related disorders are a set of behavioral, cognitive applicable to most psychiatric disorders as well. This article and physiological phenomena that occur after repeated use of a focuses on two pending questions regarding addiction: substance. These typically include: A strong desire to continue Why do some individuals become addicted while others do using a drug, difficulties in controlling its use, persistence in not? along with Is it a learned behavior or is it genetically using it although it has negative consequences, the use of the predefined? Recent data suggest that addiction is more than substance taking precedence over other activities and obliga‑ repeated exposure, it is the synchronicity between intrinsic tions, along with high tolerance and sometimes withdrawal (1). factors (genotype, sex, age, preexisting addictive disorder, New developments have altered the way we define addiction. or other mental illness), extrinsic factors (childhood, level of In this sense the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental education, socioeconomic status, social support, entourage, Disorders (5th ed.) (DSM‑5) (2) has changed the related chapter drug availability) and the nature of the addictive agent (phar‑ from ‘Substance‑Related Disorders’ to ‘Substance‑Related macokinetics, path of administration, psychoactive properties). -

Download (PDF)

Supplemental Information Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin Promoter Methylation Profiles between Human Lung Adenocarcinoma Multidrug Resistant A549/Cisplatin (A549/DDP) Cells and Its Progenitor A549 Cells Ruiling Guo, Guoming Wu, Haidong Li, Pin Qian, Juan Han, Feng Pan, Wenbi Li, Jin Li, and Fuyun Ji © 2013 The Pharmaceutical Society of Japan Table S1. Gene categories involved in biological functions with hypomethylated promoter identified by MeDIP-ChIP analysis in lung adenocarcinoma MDR A549/DDP cells compared with its progenitor A549 cells Different biological Genes functions transcription factor MYOD1, CDX2, HMX1, THRB, ARNT2, ZNF639, HOXD13, RORA, FOXO3, HOXD10, CITED1, GATA1, activity HOXC6, ZGPAT, HOXC8, ATOH1, FLI1, GATA5, HOXC4, HOXC5, PHTF1, RARB, MYST2, RARG, SIX3, FOXN1, ZHX3, HMG20A, SIX4, NR0B1, SIX6, TRERF1, DDIT3, ASCL1, MSX1, HIF1A, BAZ1B, MLLT10, FOXG1, DPRX, SHOX, ST18, CCRN4L, TFE3, ZNF131, SOX5, TFEB, MYEF2, VENTX, MYBL2, SOX8, ARNT, VDR, DBX2, FOXQ1, MEIS3, HOXA6, LHX2, NKX2-1, TFDP3, LHX6, EWSR1, KLF5, SMAD7, MAFB, SMAD5, NEUROG1, NR4A1, NEUROG3, GSC2, EN2, ESX1, SMAD1, KLF15, ZSCAN1, VAV1, GAS7, USF2, MSL3, SHOX2, DLX2, ZNF215, HOXB2, LASS3, HOXB5, ETS2, LASS2, DLX5, TCF12, BACH2, ZNF18, TBX21, E2F8, PRRX1, ZNF154, CTCF, PAX3, PRRX2, CBFA2T2, FEV, FOS, BARX1, PCGF2, SOX15, NFIL3, RBPJL, FOSL1, ALX1, EGR3, SOX14, FOXJ1, ZNF92, OTX1, ESR1, ZNF142, FOSB, MIXL1, PURA, ZFP37, ZBTB25, ZNF135, HOXC13, KCNH8, ZNF483, IRX4, ZNF367, NFIX, NFYB, ZBTB16, TCF7L1, HIC1, TSC22D1, TSC22D2, REXO4, POU3F2, MYOG, NFATC2, ENO1, -

A Bioinformatics Model of Human Diseases on the Basis Of

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS A Bioinformatics Model of Human Diseases on the basis of Differentially Expressed Genes (of Domestic versus Wild Animals) That Are Orthologs of Human Genes Associated with Reproductive-Potential Changes Vasiliev1,2 G, Chadaeva2 I, Rasskazov2 D, Ponomarenko2 P, Sharypova2 E, Drachkova2 I, Bogomolov2 A, Savinkova2 L, Ponomarenko2,* M, Kolchanov2 N, Osadchuk2 A, Oshchepkov2 D, Osadchuk2 L 1 Novosibirsk State University, Novosibirsk 630090, Russia; 2 Institute of Cytology and Genetics, Siberian Branch of Russian Academy of Sciences, Novosibirsk 630090, Russia; * Correspondence: [email protected]. Tel.: +7 (383) 363-4963 ext. 1311 (M.P.) Supplementary data on effects of the human gene underexpression or overexpression under this study on the reproductive potential Table S1. Effects of underexpression or overexpression of the human genes under this study on the reproductive potential according to our estimates [1-5]. ↓ ↑ Human Deficit ( ) Excess ( ) # Gene NSNP Effect on reproductive potential [Reference] ♂♀ NSNP Effect on reproductive potential [Reference] ♂♀ 1 increased risks of preeclampsia as one of the most challenging 1 ACKR1 ← increased risk of atherosclerosis and other coronary artery disease [9] ← [3] problems of modern obstetrics [8] 1 within a model of human diseases using Adcyap1-knockout mice, 3 in a model of human health using transgenic mice overexpressing 2 ADCYAP1 ← → [4] decreased fertility [10] [4] Adcyap1 within only pancreatic β-cells, ameliorated diabetes [11] 2 within a model of human diseases -

Early During Myelomagenesis Alterations in DNA Methylation That

Myeloma Is Characterized by Stage-Specific Alterations in DNA Methylation That Occur Early during Myelomagenesis This information is current as Christoph J. Heuck, Jayesh Mehta, Tushar Bhagat, Krishna of September 23, 2021. Gundabolu, Yiting Yu, Shahper Khan, Grigoris Chrysofakis, Carolina Schinke, Joseph Tariman, Eric Vickrey, Natalie Pulliam, Sangeeta Nischal, Li Zhou, Sanchari Bhattacharyya, Richard Meagher, Caroline Hu, Shahina Maqbool, Masako Suzuki, Samir Parekh, Frederic Reu, Ulrich Steidl, John Greally, Amit Verma and Seema B. Downloaded from Singhal J Immunol 2013; 190:2966-2975; Prepublished online 13 February 2013; doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202493 http://www.jimmunol.org/content/190/6/2966 http://www.jimmunol.org/ Supplementary http://www.jimmunol.org/content/suppl/2013/02/13/jimmunol.120249 Material 3.DC1 References This article cites 38 articles, 15 of which you can access for free at: http://www.jimmunol.org/content/190/6/2966.full#ref-list-1 by guest on September 23, 2021 Why The JI? Submit online. • Rapid Reviews! 30 days* from submission to initial decision • No Triage! Every submission reviewed by practicing scientists • Fast Publication! 4 weeks from acceptance to publication *average Subscription Information about subscribing to The Journal of Immunology is online at: http://jimmunol.org/subscription Permissions Submit copyright permission requests at: http://www.aai.org/About/Publications/JI/copyright.html Email Alerts Receive free email-alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up at: http://jimmunol.org/alerts The Journal of Immunology is published twice each month by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc., 1451 Rockville Pike, Suite 650, Rockville, MD 20852 Copyright © 2013 by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc. -

Intervention a Process – Not an Event

Intervention A Process – Not an Event ® La Hacienda PO Box 1, 145 La Hacienda Way Hunt, Texas 78024 (800) 749-6160 www.lahacienda.com Table of Contents (Please Note: Throughout this guide, items in bold italics are not printed in the Participant’s Guide.) What, Why and How of Intervention 1 Intervention Program Description 2 Rights of Intervention Program Participants 3 Responsibilities of Intervention Program Participants 3 Outline of the Intervention Process 4 The Disease 5 Nature of the Disease 6 Progression of the Disease 7 Delusional Memory 8 The Intervention Concept and Goal 9 Intervention Presentation Guidelines 10 Documentation Preparation 12 Suggested Feelings Words 13 Documentation Sheet Example 14 Documentation Sheet 15 Substance Abuse: A Family Problem 16 Symptoms of Co-Dependency 17 Enabling 18 Enabling Worksheet 19 What Goes on in a Family? 20 Intervention Planning Worksheet 21 Practice of Presentations 22 Your Intervention Rules 23 Intervention Checklist and Last Minute Reminders 24 This page intentionally left blank. What, Why and How of Intervention What is Intervention? Why Intervene? In its simplest form, intervention on Alcoholism is a progressive, alcoholism or drug addiction happens each terminal disease characterized by time the dependent person is confronted delusion and denial. Left to his/her own with his/her use or related behavior. This devices, the addicted individual is doomed form of intervention is inadequate and to continue their downward spiral. They counterproductive. Following such an have a disease that makes them think they encounter the addiction worsens and the do not have a disease! We believe that the family and friends of the dependent become belief that an alcoholic/addict must “hit angry and frustrated and may avoid further bottom” and ask for help is a deadly myth. -

USP8 Mutations in Corticotroph Adenomas Determine a Distinct Gene Expression Profile Irrespective of Functional Tumour Status

6 181 M Bujko, P Kober and Transcriptomic profiling in 181:6 615–627 Clinical Study others corticotrophinomas USP8 mutations in corticotroph adenomas determine a distinct gene expression profile irrespective of functional tumour status Mateusz Bujko1,*, Paulina Kober1,*, Joanna Boresowicz1, Natalia Rusetska1, Agnieszka Paziewska2,6, Michalina Dąbrowska2, Agata Piaścik3, Monika Pękul3, Grzegorz Zieliński4, Jacek Kunicki5, Wiesław Bonicki5, Jerzy Ostrowski2,6, Janusz A Siedlecki1 and Maria Maksymowicz3 1Department of Molecular and Translational Oncology, 2Department of Genetics, 3Department of Pathology and Laboratory Diagnostics, Maria Sklodowska-Curie Institute – Oncology Center, Warsaw, Poland, 4Department of Neurosurgery, Military Institute of Medicine, Warsaw, Poland, 5Department of Neurosurgery, Maria Sklodowska-Curie Institute – Correspondence Oncology Center, Warsaw, Poland, and 6Department of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Clinical Oncology, Medical should be addressed Center for Postgraduate Education, Warsaw, Poland to M Maksymowicz *(M Bujko and P Kober contributed equally to this work) Email [email protected] Abstract Objective: Pituitary corticotroph adenomas commonly cause Cushing’s disease (CD) but part of these tumours are hormonally inactive (silent corticotroph adenomas, SCA). USP8 mutations are well-known driver mutations in corticotrophinomas. Differences in transcriptomic profiles between functioning and silent tumours or tumours with different USP8 status have not been investigated. Design and methods: Forty-eight patients (28 CD, 20 SCA) were screened for USP8 mutations with Sanger sequencing. Twenty-four patients were included in transcriptomic profiling with Ampliseq Transcriptome Human Gene Expression Core Panel. The entire patients group was included in qRT-PCR analysis of selected genes expression. Immunohistochemistry was used for visualization of selected protein. European Journal of Endocrinology Results: We found USP8 mutation in 15 patients with CD and 4 SCAs. -

Life Mental Health

LIFE MENTAL HEALTH BIPOLAR MOOD DISORDERS TREATMENT & REFERRAL GUIDE MHealth–BR–005 Rev 2 January 2019 LIFE MENTAL HEALTH Bipolar Mood Disorders – Treatment Guide ■ How to recognise Bipolar Mood Disorder ■ Who to approach for treatment ■ Treatment options ■ Self help BIPOLAR MOOD DISORDER Bipolar mood disorder is more than just a simple mood swing. You may experience a sudden dramatic shift in the extremes of emotions. These shifts seem to have little to do with external situations. In the manic or high phase of the illness you are not just happy, but rather, ecstatic. A great burst of energy can be followed by severe depression, which is the low phase of the disease. Periods of fairly normal moods can be experienced between cycles. These cycles are different for different people. They can last for days, weeks, or even months. Although bipolar mood disorder can be disabling, it also responds well to treatment. Since many other diseases can masquerade as bipolar mood disorder, it is important that the person undergoes a complete medical evaluation as soon as possible after the first symptoms occur. What is bipolar mood disorder? Bipolar mood disorder is a physical illness marked by extreme changes in mood, energy and behaviour. That is why doctors classify it as a mood disorder. Bipolar mood disorder – which used to be known as manic depressive illness – is a mental illness involving episodes of serious mania and depression. The person’s mood usually swings from overly high and irritable to sad and hopeless, and then back again, with periods of normal mood in between. -

Altered Transcription of Glutamatergic and Glycinergic Receptors in Spinal

European Journal of Neuroscience Altered transcription of glutamatergic and glycinergic receptors in spinal cord dorsal horn following spinal cord transection is minimally affected by passive exercise of the hindlimbs For Peer Review Journal: European Journal of Neuroscience Manuscript ID Draft Manuscript Type: Research Report Date Submitted by the Author: n/a Complete List of Authors: Chopek, Jeremy; Dalhousie University, Medical Neuroscience; University of Manitoba College of Medicine, Physiology and Pathophysiology MacDonell, Chris; University of Manitoba College of Medicine, Physiology and Pathophysiology Shepard, Patricia; University of Manitoba College of Medicine, Physiology and Pathophysiology Gardiner, Kalan; University of Manitoba College of Medicine, Physiology and Pathophysiology Gardiner, PF; University of Manitoba, Physiology and Pathophysiology Key Words: Spinal cord injury, gene expression, dorsal horn, exercise Page 5 of 32 European Journal of Neuroscience Dorsal horn gene expression following STx Journal Section: Molecular and synaptic mechanisms Title: Altered transcription of glutamatergic and glycinergic receptors in spinal cord dorsal horn following spinal cord transection is minimally affected by passive exercise of the hindlimbs Authors: Jeremy W.For Chopek, PeerChristopher W. Review MacDonell, Patricia C. Shepard, Kalan R. Gardiner, Phillip F Gardiner Affiliations: Spinal Cord Research Centre, Department of Physiology and Pathophysiology, Rady Faculty of Health, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB, R3E 0J9 Running -

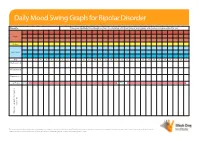

Daily Mood Swing Graph for Bipolar Disorder

Daily Mood Swing Graph for Bipolar Disorder Month: Please use this Daily Mood Graph to chart mood swings and the effects of any triggers and medications prescribed for you. Highs Normal Depressed Day 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 Medication A Medication B Medication C e.g. Prozac 20mg 40mg events, etc. events, Notes on sleep patterns, triggers, triggers, on sleep patterns, Notes This document may be freely downloaded and distributed on condition no change is made to the content. The information in this document is not intended as asubstitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. Not to be used for commercial purposes and not to be hosted electronically outside of the Black Dog Institute website. www.blackdoginstitute.org.au Daily Mood Swing Graph for Bipolar Disorder Instructions 1. Rate your mood at the end of each day by placing an ‘X’ in the appropriate box. If you have experienced both a ‘high’ and a ‘low’ mood on any given day, please rate both by putting an ‘X’ at each level 2. Write the name of the medications and doses you are taking 3. Next to each medication, please indicate the period of time you took the medication at the same dose by drawing an arrow through the relevant dates. If your dose changes during the course of the charting period, please write the new dose in the relevant box and continue the line.