Of Contemporary Mormon Short Stories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Taking Mormons Seriously: Ethics of Representing Latter-Day Saints in American Fiction

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2007-07-10 Taking Mormons Seriously: Ethics of Representing Latter-day Saints in American Fiction Terrol Roark Williams Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Williams, Terrol Roark, "Taking Mormons Seriously: Ethics of Representing Latter-day Saints in American Fiction" (2007). Theses and Dissertations. 1159. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/1159 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. TAKING MORMONS SERIOUSLY: ETHICS OF REPRESENTING LATTER-DAY SAINTS IN AMERICAN FICTION by Terrol R. Williams A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of English Brigham Young University August 2007 BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY GRADUATE COMMITTEE APPROVAL of a thesis submitted by Terrol R. Williams This thesis has been read by each member of the following graduate committee and by majority vote has been found to be satisfactory. Date Gideon O. Burton, Chair Date Susan Elizabeth Howe, Reader Date Phillip A. Snyder, Reader Date Frank Q. Christianson, Graduate Advisor Date Nicholas Mason, Associate Chair -

CHAPTER SIX Work and Worship C C

88 C c CHAPTER SIX Work and Worship C c Construction of the tabernacle on Temple Square, 1866. ineteenth-century Mormons differentiated little between “Ten Acre Survey” and all the land lying east of it. Westward temporal and spiritual concerns. The physical act of gath- it extended to the Jordan River. According to some historians, ering to Zion showed their faithfulness more than atten- the ward for several years had the largest membership in the Ndance at Sunday meetings;1 discouraging Gentile influence church.4 by participating in community production efforts and shopping Attendance at ward meetings was probably small, typical of at church cooperative stores seemed nearly as essential as the attendance throughout the territory. In 1851 Brigham Young payment of tithes. Living some distance from Salt Lake City complained, merchants, the Birch and Morgan families undoubtedly relied Suppose I should appoint a meeting for tonight, about more than townsfolk on bartering with neighbors. Similarly, ru- a dozen [members] would come, [and] without any ral conditions and distance from church headquarters probably candles. [But] if I were to say—level this stand for the influenced ward activities and the structure of meetings2—but band that we may have a dance, they would bring the not essential ordinances or the importance of community wor- stoves from their wives’ bedsides, and would dance all ship and community work. night, and the house would be filled to overflowing.5 Millcreek Ward Historian Ronald Walker cites the ten to fifteen percent -

Mormon Novels Entertain While Teaching Lessons

SUNSTONE BOOKS MORMON NOVELS ENTERTAIN WHILE TEACHING LESSONS by Peggy Fletcher Stack Tribune religion writer This story orignally appeared in the 10 October 1998 Salt Lake Tribune. Reprinted in its entirety by permission. The world of romance novels seethes with heaving bosoms, manly men, seduction, betrayal. Mormon novels have all of that and then some-excommunica- tion, repentance, prayer, re- demution. In the past few years, popular Today's wxnovels deal with serious topics-abuse, adultery, date rape- fiction-romance, mystery and but they have Mormon theology-based solutions. historical novels-aimed at members of The Church of Jesus Too, such books are peopled they are getting something out of Since then, Weyland, a Christ of Latter-day Saints has with recognizable LDS charac- it." physics professor at LDS-owned been selling by the barrelful. ters-Brigham Young University 100 Years: The first Mormon Ricks College in Rexburg, Idaho, Anita Stansfield has sold more students, missionaries, converts, popular novel may have been has written a dozen more, many than two hundred thousand bishops, Relief Society presi- Added Upon, written by Nephi of them almost as successful. copies of her work. Jack Weyland dents, religion professors, home Anderson in 1898, Cracroft says. "The ones that have done the routinely sells between twenty schoolers. It told the story of an LDS best are all issue-related," says and thirty thousand novels And they are laced with theo- I couple who met in a pre-Earth Emily Watts, an associate editor aimed at the LDS teen market. logcal certainty existence and agreed to get to- at Deseret Book who has worked The hbrk and the Glory, a "Lots of Mormons feel they gether in mortal life. -

The Poetics of Provincialism: Mormon Regional Fiction

The Poetics of Provincialism: Mormon Regional Fiction EDWARD A. GEARY THE LATTER-DAY SAINTS have been a source of sensationalistic subject matter for popular novelists almost since the beginning of the Church. But the Mormon novel as a treatment of Mormon materials from a Mormon point of view has come from two main wellsprings. The first was the "home literature" movement of the 1880s, the goal of which, according to Orson F. Whitney, was to produce a "pure and powerful literature" as an instrument for spreading the gospel, a literature which, "like all else with which we have to do, must be made subservient to the building up of Zion."1 Even though its early practitioners are little read today—Nephi Anderson is the chief exception—the influence of home literature remains strong. It provides the guiding principles by which fiction and poetry are selected for the official church magazines, and it is also reflected in such popular works in Mormondom as Saturday's Warrior and Beyond This Moment. However, home literature has not had the impact on the world that Brother Whitney hoped for. It has not led to the development of "Miltons and Shakespeares of our own."2 Good fiction is seldom written to ideological specifications. It is one thing to ask the artist to put his religious duties before his literary vocation or to write from his deepest convictions. It is quite another to insist that he create from a base in dogma rather than a base in experience. Good fiction, as Virginia Sorensen has said, is "one person's honest report upon life,"3 and in home literature the report usually fails to ring true. -

REVIEWS Forgeries, Bombs, and Salamanders

REVIEWS Forgeries, Bombs, and Salamanders Salamander: The Story of the Mormon style worked very well in this case. The Forgery Murders by Linda Sillitoe and lack of documentation could be seen as a Allen D. Roberts, with a forensic analysis weakness, but I assume that several sources by George J. Throckmorton (Salt Lake did not want to be quoted and the popular City: Signature Books, 1988), xiii+556 pp., format did not lend itself to footnotes. It $17.95. could also be argued that the book would be too expensive if the extra documenta- Reviewed by Jeffery Ogden Johnson, tion were published. I hope future re- Utah State Archivist, Salt Lake City, Utah. searchers will have access to the research notes, including the many interviews. EVERY ONCE IN A WHILE you will see an The book opens with an account of the image that stays with you for years. On two murders. It details the cold-blooded 16 October 1985 I saw an image that will way Hofmann went about the business of be with me a lifetime: a burned out sports killing his friend Steve Christensen and by- car and yellow ribbons cordoning off the stander Kathy Sheets on 15 October 1985. street behind Deseret Gym. The yellow It was the bomb that went off the next day ribbons had been put there by the police and destroyed Hofmann's sports car that to keep the curious back. The burned out connected Hofmann with the mystery. This sports car belonged to Mark Hofmann. As book cannot ascertain with surety the target I drove by the scene on my way home from of the third bomb, but the authors argue work, I did not realize how the bomb would that it was not a suicide attempt as Hof- affect the Mormon scholarly community. -

Mormon Literature: Progress and Prospects by Eugene England

Mormon Literature: Progress and Prospects By Eugene England This essay is the culmination of several attempts England made throughout his life to assess the state of Mormon literature and letters. The version below, a slightly revised and updated version of the one that appeared in David J. Whittaker, ed., Mormon Americana: A Guide to Sources and Collections in the United States (Provo, Utah: BYU Studies, 1995), 455–505, is the one that appeared in the tribute issue Irreantum published following England’s death. Originally published in: Irreantum 3, no. 3 (Autumn 2001): 67–93. This, the single most comprehensive essay on the history and theory of Mormon literature, first appeared in 1982 and has been republished and expanded several times in keeping up with developments in Mormon letters and Eugene England’s own thinking. Anyone seriously interested in LDS literature could not do better than to use this visionary and bibliographic essay as their curriculum. 1 ExpEctations MorMonisM hAs bEEn called a “new religious tradition,” in some respects as different from traditional Christianity as the religion of Jesus was from traditional Judaism. 2 its beginnings in appearances by God, Jesus Christ, and ancient prophets to Joseph smith and in the recovery of lost scriptures and the revelation of new ones; its dramatic history of persecution, a literal exodus to a promised land, and the build - ing of an impressive “empire” in the Great basin desert—all this has combined to make Mormons in some ways an ethnic people as well as a religious community. Mormon faith is grounded in literal theophanies, concrete historical experience, and tangible artifacts (including the book of Mormon, the irrigated fields of the Wasatch Front, and the great stone pioneer temples of Utah) in certain ways that make Mormons more like ancient Jews and early Christians and Muslims than, say, baptists or Lutherans. -

Danger on the Right! Danger on the Left!: the Ethics of Recent Mormon Fiction by Eugene England

Danger on the Right! Danger on the Left!: The Ethics of Recent Mormon Fiction By Eugene England An essay in which England decries a trend in LDS fiction away from “ethical fiction,” which he describes as having the purpose of persuading us “to understand better the values we do or might live by and thus to choose better, to be more humane, sympathetic, compas - sionate, at least more courageous, more able to endure.” Originally published : Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 32, no.3 (Fall 1999), 13–30. HE FIRST EXAMPLE of what could be called a Mormon short story was T written by an apostle, Parley P. Pratt. It was published in the New York Herald on January 1, 1844, and collected in Richard Cracroft’s and Neal Lambert’s anthol - ogy, A Believing People: Literature of the Latter-day Saints (Provo, Utah: BYU Press, 1974). It is called “A Dialogue between Joe Smith and the Devil” and is quite witty, imaginative in setting and characterization, lively in its language, and, though clearly pro-Mormon, aimed at a non-Mormon audience. It consists wholly of a conversation between Joseph Smith and “his Satanic majesty,” whom Joseph inter - rupts putting up handbills calling for all “busy bodies, pickpockets, vagabonds, filthy persons, and all other infidels and rebellious, disorderly persons, for a crusade against . the Mormons.” The story has an obvious didactic purpose, as Elder Pratt has the Devil bring up most of the central precepts of Mormon doctrine, such as “direct communication with God,” and then indirectly praise them by pointing out how powerful they are and destructive to his own evil purposes. -

FINGER of GOD?: Claims and Controversies of Book of Mormon Translation 30 Kevin Cantera

00a_working cover_bottom:Cover.qxd 12/10/2010 2:57 Pm Page 2 SUNSTONE MORMON EXPERIENCE,, SCHOLARSHIP, ISSUUEESS,, ANDD ARTT written by the the by by written written fingerfinger ofof God?God? Claims and Controversies of Book of Mormon Translation Translation by Don Bradley december 2010—$7.50 uTahuTah eugeneeugene inTerviewinTerview TheThe FamilyFamily CounTy’sCounTy’s england’sengland’s withwith TheThe LonelyLonely Forum:Forum: dreamdream minemine byby CalCulaTedCalCulaTed PolygamistPolygamist authorauthor AA New New ColumNColumN kevinkevin CanteraCantera riskrisk byby BradyBrady udalludall byby michaelmichael (p.31)(p.31) CharlotteCharlotte (p.66)(p.66) FarnworthFarnworth (p.57)(p.57) hansenhansen (p.38)(p.38) 00b_inside cover:cover.qxd 12/2/2010 11:18 pm page 1 Your year-end Our Loyal donation To: Thanks he ers makes all t subscrib difference. SUNSTONE invites writers to enter the 2011 Eugene England Memorial Personal Essay Contest, made possible by the Eugene and Charlotte England Education Fund. In the spirit of Gene’s writings, entries should relate to Latter-day Saint experience, theology, or worldview. Essays, without author identification, will be judged by noted Mormon authors and professors of literature. Winners will be announced by 31 May 2011 on Sunstone’s website, SUNSTONEMAGAZINE.COM. Winners only will be notified by mail. After the announcement, all other entrants will be free to submit their stories elsewhere. PRIZES: A total of $450 will be shared among the winning entries. RULES: 1. Up to three entries may be submitted by any one author. Send manuscript in PDF or Word format to [email protected] by 28 FEBRUARY 2011. 2. -

The Function of Mormon Literary Criticism at the Present Time

NOTES AND COMMENTS The Function of Mormon Literary Criticism at the Present Time Michael Austin IN HIS HILARIOUS SHORT STORY "Conversion of the Jews/' Philip Roth gives us one of the most endearing unimportant characters in our national lit- erature: Yakov Blotnik, an old janitor at a Jewish Yeshiva who, upon see- ing that a yeshiva student was standing on a ledge threatening to kill himself, goes off mumbling to himself that such goings-on are "no-good- for-the-Jews." "For Yakov Blotnik," Roth tells us in an aside, "life frac- tionated itself simply: things were either good-for-the-Jews or no-good- for-the-Jews."1 This basic binary opposition, which I have named the "Blotnik dichotomy" in honor of its distinguished inventor, has, with mi- nor variations and revisions, begun to assert itself prominently in a num- ber of recent discussions of Mormon literature. The taxonomies that have come from these discussions tend to dichotomize Mormon letters into separate camps—such as "mantic" versus "sophic," "faithful realism" versus "faithless fiction," or "home literature" versus "the Lost Genera- tion."2 Each of these pairings suggests that at the heart of the Mormon lit- erary consciousness lies a conception that Mormon literature can be 1. Philip Roth, Goodbye Columbus (New York: Bantam, 1963), 108. 2. Most of these terms have been in wide use by scholars of Mormon literature for some time. The "mantic-sophic" dichotomy was introduced by Richard Cracroft in his presidential address at the Association for Mormon Letters in 1992, which was later published as "Attun- ing the Authentic Mormon Voice: Stemming the Sophic Tide in LDS Literature," Sunstone 16 (July 1993): 51-57. -

I UTAH Discouraged at Being So Little Able to 1760 S

A WORD FROM THE PUBLISHER Daniel Rector 3 MY BURDEN IS LIGHT Elbert Eugene Peck OF GODS, MORTALS, AND DEVILS Boyd Kirkland 6 As Satan Is, Man may yet become SUNSWATH Levi Peterson 13 First Place Story in the 1986 D.K. Brown Fiction Contest PERCEPTIONS OF LIFE Louis A. Moench 30 Four Paths on Our Journey through Life THE MORMON DOCUMENTS’ Linda Sillitoe ~3 DAY IN COURT A Closer Look at Some Historical Documents RECORD TURNOUT AT SYMPOSIUM EIGHT 4O NEW DIRECTOR FOR SMITH INSTITUTE 41 LDS POET MEG MUNK DEAD AT 42 PROPHET IN THE PROMISED LAND Richard W. Sadler 44 Brigham Young: American Moses by Leonard J. Arrington SIN OR BORE? Kerry William Bate Mormon Polygamy: A History by Richard Van Wagoner READERS FORUM PUBLISHER Daniel H. Rector ALL-TIME LOW breakdowns, poor health anc! low EDITOR Elbert Eu,¢;ene Peck grades. It is not the reason gifted ASSOCIATE EDITOR Ron t~:itton In publishing the vicious LDS artists and scholars DESIGN DIRFCTOR Connie Disney personal attack on Linda Newell underachieve. GRAPHICS Robyn Smith Winchester (SUNSTONE, 10:11), SUNSTONE ART EDITOR Patrick Baxley reached an all-time low. It should Seminary is not a Primary class CIRCU~TION MANAGER Hden E. Wright be beneath the dignity of a that meets daily. It is a high school OPERATIONS MANAGER Charlotte Hamblin respectable journal to disseminate level course in theology. One EOITING INTERN Mdissa Sillitoe such a scurrilous statement. cannot become a good pianisl: through a correspondence school. NATIONAL CORRESPONDENTS Irene Bates, Bonnie Sterling M. McMur~m The best way to teach M. -

Representations of Mormonism in American Culture Jeremy R

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository American Studies ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 8-19-2011 Imagining the Saints: Representations of Mormonism in American Culture Jeremy R. Ricketts Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/amst_etds Part of the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Ricketts, eJ remy R.. "Imagining the Saints: Representations of Mormonism in American Culture." (2011). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/amst_etds/37 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in American Studies ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Jeremy R. Ricketts Candidate American Studies Departmelll This dissertation is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Dissertation Commillee: , Chairperson Alex Lubin, PhD &/I ;Se, tJ_ ,1-t C- 02-s,) Lori Beaman, PhD ii IMAGINING THE SAINTS: REPRESENTATIONS OF MORMONISM IN AMERICAN CULTURE BY JEREMY R. RICKETTS B. A., English and History, University of Memphis, 1997 M.A., University of Alabama, 2000 M.Ed., College Student Affairs, 2004 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy American Studies The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico May 2011 iii ©2011, Jeremy R. Ricketts iv DEDICATION To my family, in the broadest sense of the word v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation has been many years in the making, and would not have been possible without the assistance of many people. My dissertation committee has provided invaluable guidance during my time at the University of New Mexico (UNM). -

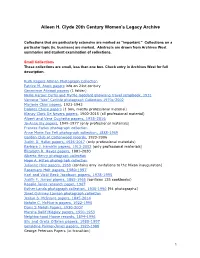

Clyde Archive Finding

Aileen H. Clyde 20th Century Women's Legacy Archive Collections that are particularly extensive are marked as “important.” Collections on a particular topic (ie. business) are marked. Abstracts are drawn from Archives West summaries and student examination of collections. Small Collections These collections are small, less than one box. Check entry in Archives West for full description. Ruth Rogers Altman Photograph Collection Patrice M. Arent papers info on 21st century Genevieve Atwood papers (1 folder) Nellie Harper Curtis and Myrtle Goddard Browning travel scrapbook, 1931 Vervene “Vee” Carlisle photograph Collection 1970s-2002 Marjorie Chan papers, 1921-1943 Dolores Chase papers (1 box, mostly professional material) Klancy Clark De Nevers papers, 1900-2015 (all professional material) Albert and Vera Cuglietta papers, 1935-2016 Jo-Anne Ely papers, 1949-1977 (only professional materials) Frances Farley photograph collection Anne Marie Fox Felt photograph collection, 1888-1969 Garden Club of Cottonwood records, 1923-2006 Judith D. Hallet papers, 1926-2017 (only professional materials) Barbara J. Hamblin papers, 1913-2003 (only professional materials) Elizabeth R. Hayes papers, 1881-2020 Alberta Henry photograph collection Hope A. Hilton photograph collection Julianne Hinz papers, 1969 (contains only invitations to the Nixon inauguration) Rosemary Holt papers, 1980-1997 Karl and Vicki Beck Jacobson papers, 1978-1995 Judith F. Jarrow papers, 1865-1965 (contains 135 cookbooks) Rosalie Jones research paper, 1967 Esther Landa photograph collection, 1930-1990 [94 photographs] Janet Quinney Lawson photograph collection Jerilyn S. McIntyre papers, 1845-2014 Natalie C. McMurrin papers, 1922-1995 Doris S Melich Papers, 1930-2007 Marsha Ballif Midgley papers, 1950-1953 Neighborhood House records, 1894-1996 Stu and Greta O’Brien papers, 1980-1997 Geraldine Palmer-Jones papers, 1922-1988 George Peterson Papers (in transition) 1 Ann Pingree Collection, 2011 Charlotte A.