Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brief Guide to the Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry

1 Brief Guide to the Nomenclature of Table 1: Components of the substitutive name Organic Chemistry (4S,5E)-4,6-dichlorohept-5-en-2-one for K.-H. Hellwich (Germany), R. M. Hartshorn (New Zealand), CH3 Cl O A. Yerin (Russia), T. Damhus (Denmark), A. T. Hutton (South 4 2 Africa). E-mail: [email protected] Sponsoring body: Cl 6 CH 5 3 IUPAC Division of Chemical Nomenclature and Structure suffix for principal hept(a) parent (heptane) one Representation. characteristic group en(e) unsaturation ending chloro substituent prefix 1 INTRODUCTION di multiplicative prefix S E stereodescriptors CHEMISTRY The universal adoption of an agreed nomenclature is a key tool for 2 4 5 6 locants ( ) enclosing marks efficient communication in the chemical sciences, in industry and Multiplicative prefixes (Table 2) are used when more than one for regulations associated with import/export or health and safety. fragment of a particular kind is present in a structure. Which kind of REPRESENTATION The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) multiplicative prefix is used depends on the complexity of the provides recommendations on many aspects of nomenclature.1 The APPLIED corresponding fragment – e.g. trichloro, but tris(chloromethyl). basics of organic nomenclature are summarized here, and there are companion documents on the nomenclature of inorganic2 and Table 2: Multiplicative prefixes for simple/complicated entities polymer3 chemistry, with hyperlinks to original documents. An No. Simple Complicated No. Simple Complicated AND overall -

International Naming Conventions NAFSA TX State Mtg

1 2 3 4 1. Transcription is a more phonetic interpretation, while transliteration represents the letters exactly 2. Why transcription instead of transliteration? • Some English vowel sounds don’t exist in the other language and vice‐versa • Some English consonant sounds don’t exist in the other language and vice‐versa • Some languages are not written with letters 3. What issues are related to transcription and transliteration? • Lack of consistent rules from some languages or varying sets of rules • Country variation in choice of rules • Country/regional variations in pronunciation • Same name may be transcribed differently even within the same family • More confusing when common or religious names cross over several countries with different scripts (i.e., Mohammad et al) 5 Dark green countries represent those countries where Arabic is the official language. Lighter green represents those countries in which Arabic is either one of several official languages or is a language of everyday usage. Middle East and Central Asia: • Kurdish and Turkmen in Iraq • Farsi (Persian) and Baluchi in Iran • Dari, Pashto and Uzbek in Afghanistan • Uyghur, Kazakh and Kyrgyz in northwest China South Asia: • Urdu, Punjabi, Sindhi, Kashmiri, and Baluchi in Pakistan • Urdu and Kashmiri in India Southeast Asia: • Malay in Burma • Used for religious purposes in Malaysia, Indonesia, southern Thailand, Singapore, and the Philippines Africa: • Bedawi or Beja in Sudan • Hausa in Nigeria • Tamazight and other Berber languages 6 The name Mohamed is an excellent example. The name is literally written as M‐H‐M‐D. However, vowels and pronunciation depend on the region. D and T are interchangeable depending on the region, and the middle “M” is sometimes repeated when transcribed. -

Minutes of the IUPAC Chemical Nomenclature and Structure Representation Division (VIII) Committee Meeting Boston, MA, USA, August 18, 2002

Minutes of the IUPAC Chemical Nomenclature and Structure Representation Division (VIII) Committee Meeting Boston, MA, USA, August 18, 2002 Members Present: Dr Stephen Heller, Prof Herbert Kaesz, Prof Dr Alexander Lawson, Prof G. Jeffrey Leigh, Dr Alan McNaught (President), Dr. Gerard Moss, Prof Bruce Novak, Dr Warren Powell (Secretary), Dr William Town, Dr Antony Williams Members Absent: Dr. Michael Dennis, Prof Michael Hess National representatives Present: Prof Roberto de Barros Faria (Brazil) The second meeting of the Division Committee of the IUPAC Division of Chemical Nomenclature and Structure Representation held in the Great Republic Room of the Westin Hotel in Boston, Massachusetts, USA was convened by President Alan McNaught at 9:00 a.m. on Sunday, August 18, 2002. 1.0 President McNaught welcomed the members to this meeting in Boston and offered a special welcome to the National Representative from Brazil, Prof Roberto de Barros Faria. He also noted that Dr Michael Dennis and Prof Michael Hess were unable to be with us. Each of the attendees introduced himself and provided a brief bit of background information. Housekeeping details regarding breaks and lunch were announced and an invitation to a reception from the U. S. National Committee for IUPAC on Tuesday, August 20 was noted. 2.0 The agenda as circulated was approved with the addition of a report from Dr Moss on the activity on his website. 3.0 The minutes of the Division Committee Meeting in Cambridge, UK, January 25, 2002 as posted on the Webboard (http://www.rsc.org/IUPAC8/attachments/MinutesDivCommJan2002.rtf and http://www.rsc.org/IUPAC8/attachments/MinutesDivCommJan2002.pdf) were approved with the following corrections: 3.1 The name Dr Gerard Moss should be added to the members present listing. -

Issues in the Linguistics of Onomastics

Journal of Lexicography and Terminology, Volume 1, Issue 2 Issues in the Linguistics of Onomastics By Vincent M. Chanda School of Humanities and Social Science University of Zambia Email: mchanda@@gmail.com Abstract Names, also called proper names or proper nouns, are very important to mankind that there is no human language without names and, for some types of names, there are written or unwritten naming conventions. The social importance of names is also the reason why onomastics, the study of names, is a multidisciplinary field. After briefly discussing the multidisciplinary nature of onomastics, the article proves the following view stated and proved by many a scholar: proper names have a grammar that includes some grammatical features of common nouns. In so doing, the article shows that, like common nouns, proper names show cross linguistic differences. To prove that names do have a grammar which in some aspects differs from the grammar of common nouns, the article often compares proper names and common nouns. Furthermore, the article uses data from several languages in addition to English. After a bief discussion of orthographic differences between proper names and common nouns, the article focuses on the morphology, both inflectional and lexical, and the syntax of proper names. Key words: Name, common noun, onomastics, multidisciplinary, naming convention, typology of names, anthroponym, inflectional morphology, lexical morphology, derivation, compounding, syntac. 67 Journal of Lexicography and Terminology, Volume 1, Issue 2 1. Introduction Onomastics or onomatology, is the study of proper names. Proper names are terms used as a means of identification of particular unique beings. -

7 Naming Customs from Around the World

7 Naming Customs From Around the World http://blog.tesol.org/7-naming-customs-from-around-the-world/ Posted on 30 July 2015 by Judie Haynes Immigrant students in the United States have already suffered the trauma of leaving behind their extended family, friends, teachers, and schools. They enter a U.S. school and can also lose their name. Their name may be deliberately changed by parents or school staff, or an error may be made in the order of the name or its spelling. These mistakes can have lasting effects on students. A person’s name is part of his or her cultural identity, and it is up to schools to get it right. In order for teachers, administrators, or office staff in your school to enroll students with the correct the name, they need to understand the naming conventions of different cultures. Here are seven naming customs from different cultures. Korean names are written with the family name first. If Yeon Suk has the family name “Lee,” his name will be written Lee Yeon Suk. The given name usually has two parts, and it follows the family name. Either part of the given name can be a generation marker: Two- part given names should not be shortened— that is, Lee Yeon Suk should be called Yeon Suk, not Yeon. Russian names have three parts: a given name, a patronymic (a middle name based on the father’s first name), and the father’s surname. If Viktor Aleksandrovich Rakhmaninov has two children, his daughter’s name would be Svetlana Viktorevna Rakhmaninova. -

Dialogue on the Nomenclature and Classification of Prokaryotes

G Model SYAPM-25929; No. of Pages 10 ARTICLE IN PRESS Systematic and Applied Microbiology xxx (2018) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Systematic and Applied Microbiology journal homepage: www.elsevier.de/syapm Dialogue on the nomenclature and classification of prokaryotes a,∗ b Ramon Rosselló-Móra , William B. Whitman a Marine Microbiology Group, IMEDEA (CSIC-UIB), 07190 Esporles, Spain b Department of Microbiology, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602, USA a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Keywords: The application of next generation sequencing and molecular ecology to the systematics and taxonomy Bacteriological code of prokaryotes offers enormous insights into prokaryotic biology. This discussion explores some major Taxonomy disagreements but also considers the opportunities associated with the nomenclature of the uncultured Nomenclature taxa, the use of genome sequences as type material, the plurality of the nomenclatural code, and the roles Candidatus of an official or computer-assisted taxonomy. Type material © 2018 Elsevier GmbH. All rights reserved. Is naming important when defined here as providing labels Prior to the 1980s, one of the major functions of Bergey’s Manual for biological entities? was to associate the multiple names in current usage with the cor- rect organism. For instance, in the 1948 edition of the Manual, 21 Whitman and 33 names were associated with the common bacterial species now named Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis, respectively [5]. When discussing the nomenclature of prokaryotes, we must first This experience illustrates that without a naming system gener- establish the role and importance of naming. -

Names, Signatures and Images of Individuals; Fictitious Character, Titles

19.6.2020 Names, signatures and images of individuals; fictitious character, titles of books, films and songs Registrability of surnames and personal names The principles for assessing the distinctive character of marks constituted by surnames have been considered in the European Court of Justice's ("ECJ") judgment in Case C-404/02 Nichols plc v Registrar of Trade Marks [2005] R.P.C. 12. In Nichols, the ECJ confirmed that the assessment of the distinctive character of a trade mark constituted by a surname, even a common one, must be carried out specifically, in accordance with the criteria applicable to any sign, in relation, first, to the products or services in respect of which registration is applied for and, second to the perception of the relevant consumers. The criteria for assessment of the distinctive character of trade marks constituted by a personal name are the same as those applicable to other categories of trade marks. Stricter general criteria of assessment based on: - a predetermined number of persons with the same name, above which that name may be regarded as devoid of distinctive character, - the number of undertakings providing products or services of the type covered by the application for registration, or - the prevalence or otherwise of the use of surnames in the relevant trade cannot be applied to surname marks as a rule-of-thumb. IPD HKSAR 1 Trade Marks Registry Registration of a trade mark constituted by a surname cannot be refused for the purpose of ensuring that no advantage is afforded to the first applicant for registration. All relevant facts and circumstances should be taken into account. -

What's in an Irish Name?

What’s in an Irish Name? A Study of the Personal Naming Systems of Irish and Irish English Liam Mac Mathúna (St Patrick’s College, Dublin) 1. Introduction: The Irish Patronymic System Prior to 1600 While the history of Irish personal names displays general similarities with the fortunes of the country’s place-names, it also shows significant differences, as both first and second names are closely bound up with the ego-identity of those to whom they belong.1 This paper examines how the indigenous system of Gaelic personal names was moulded to the requirements of a foreign, English-medium administration, and how the early twentieth-century cultural revival prompted the re-establish- ment of an Irish-language nomenclature. It sets out the native Irish system of surnames, which distinguishes formally between male and female (married/ un- married) and shows how this was assimilated into the very different English sys- tem, where one surname is applied to all. A distinguishing feature of nomen- clature in Ireland today is the phenomenon of dual Irish and English language naming, with most individuals accepting that there are two versions of their na- me. The uneasy relationship between these two versions, on the fault-line of lan- guage contact, as it were, is also examined. Thus, the paper demonstrates that personal names, at once the pivots of individual and group identity, are a rich source of continuing insight into the dynamics of Irish and English language contact in Ireland. Irish personal names have a long history. Many of the earliest records of Irish are preserved on standing stones incised with the strokes and dots of ogam, a 1 See the paper given at the Celtic Englishes II Colloquium on the theme of “Toponyms across Languages: The Role of Toponymy in Ireland’s Language Shifts” (Mac Mathúna 2000). -

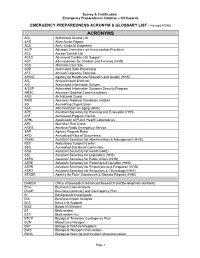

ACRONYM & GLOSSARY LIST - Revised 9/2008

Survey & Certification Emergency Preparedness Initiative – All Hazards EMERGENCY PREPAREDNESS ACRONYM & GLOSSARY LIST - Revised 9/2008 ACRONYMS AAL Authorized Access List AAR After-Action Report ACE Army Corps of Engineers ACIP Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices ACL Access Control List ACLS Advanced Cardiac Life Support ACF Administration for Children and Families (HHS) ACS Alternate Care Site ADP Automated Data Processing AFE Annual Frequency Estimate AHRQ Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (HHS) AIE Annual Impact Estimate AIS Automated Information System AISSP Automated Information Systems Security Program AMSC American Satellite Communications ANG Air National Guard ANSI American National Standards Institute AO Accrediting Organization AoA Administration on Aging (HHS) APE Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (HHS) APF Authorized Program Facility APHL Association of Public Health Laboratories ARC American Red Cross ARES Amateur Radio Emergency Service ARF Agency Request Form ARO Annualized Rate of Occurrence ASAM Assistant Secretary for Administration & Management (HHS) ASC Ambulatory Surgical Center ASC Accredited Standards Committee ASH Assistant Secretary for Health (HHS) ASL Assistant Secretary for Legislation (HHS) ASPA Assistant Secretary for Public Affairs (HHS) ASPE Assistant Secretary for Planning & Evaluation (HHS) ASPR Assistant Secretary for Preparedness & Response (HHS) ASRT Assistant Secretary for Resources & Technology (HHS) ATSDR Agency for Toxic Substances & Disease Registry (HHS) BARDA -

Principles for the Consistent Use of Place Names

Principles for the Consistent Use of Place Names includes Principles for the Use of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Place Names and Dual Naming Depiction Principles Permanent Committee on Place Names Edition History March 2009 June 2009 September 2011 April 2012 September 2012 April 2014 Corrections to cross-references, p.10 (4.23) and p.17 (Item 1). May 2014 Web-link updated (p. 5); minor revisions to style and usage. March 2015 Revisions to 4.6, 4.8 (added), 4.14, 4.20, 4.23, 4.26, 4.27 (added), 4.28 (added) December 2015 Update to Committee names and style; 4.19 revised This Edition: October 2016 New title to the document; terms of reference statement updated; 4.19 revised 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS PRINCIPLES FOR THE CONSISTENT USE OF PLACE NAMES ...................................... 5 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................... 5 2 Place Names Authorities ............................................................................................... 6 3 Permanent Committee on Place Names ....................................................................... 6 4 Guidelines ...................................................................................................................... 7 4.1 Official Language .................................................................................................... 7 4.2 Names Governed by Statutory or Administrative Authority ..................................... 7 4.3 Official or Approved Names -

Party Name Side Note

ISB Publication Doc Ref: ISB-000075 Party Name Side Note Version: 2.0 Issue Date: 26/04/2016 Document Version History Modified Version Status Issue Date by Description 1.0 Approved: 06/05/2014 ISB Guidance note for Party Recommended Name documentation 2.0 Approved: 26/04/2016 TSS Updated to align with model Recommended changes © Crown copyright 2016 Party Name Side Note Contents 1 Introduction ________________________________________________ 4 1.1 Purpose ______________________________________________________ 4 1.2 Scope ________________________________________________________ 5 1.3 Business Data Architecture (BDA) Model Version ______________________ 5 2 Design Concept _____________________________________________ 6 2.1 Business Requirements __________________________________________ 6 2.1.1 (Party of type) Person ________________________________________________ 6 2.1.2 (Party of type) Organisation ___________________________________________ 7 2.1.3 Common (to both person and organisation types of Party) ___________________ 7 2.2 Entity Definition Models __________________________________________ 8 2.3 Attribute Models ________________________________________________ 9 3 How the Structure resolves the Business Requirements __________ 10 3.1 Multiple names ________________________________________________ 10 3.2 Re-usable name bank __________________________________________ 11 3.3 Parsing a name _______________________________________________ 12 3.4 Name components ordering ______________________________________ 13 3.5 Single design for -

African Names and Naming Practices: the Impact Slavery and European

African Names and Naming Practices: The Impact Slavery and European Domination had on the African Psyche, Identity and Protest THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Liseli A. Fitzpatrick, B.A. Graduate Program in African American and African Studies The Ohio State University 2012 Thesis Committee: Lupenga Mphande, Advisor Leslie Alexander Judson Jeffries Copyrighted by Liseli Anne Maria-Teresa Fitzpatrick 2012 Abstract This study on African naming practices during slavery and its aftermath examines the centrality of names and naming in creating, suppressing, retaining and reclaiming African identity and memory. Based on recent scholarly studies, it is clear that several elements of African cultural practices have survived the oppressive onslaught of slavery and European domination. However, most historical inquiries that explore African culture in the Americas have tended to focus largely on retentions that pertain to cultural forms such as religion, dance, dress, music, food, and language leaving out, perhaps, equally important aspects of cultural retentions in the African Diaspora, such as naming practices and their psychological significance. In this study, I investigate African names and naming practices on the African continent, the United States and the Caribbean, not merely as elements of cultural retention, but also as forms of resistance – and their importance to the construction of identity and memory for persons of African descent. As such, this study examines how European colonizers attacked and defiled African names and naming systems to suppress and erase African identity – since names not only aid in the construction of identity, but also concretize a people’s collective memory by recording the circumstances of their experiences.