An Examination of Existing and Emerging Hispanic-Serving Institutions’ Latino Initiatives and Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Department of Student & Financial Aid Services

Department of Student & Financial Aid Services Policies & Procedures Manual Working Draft Effective Academic Year 2019-2020 By: Ululy R. Martinez, Esq. Date: June 14, 2019 Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 10 CHAPTER 1: Components of the Financial Aid System ................................................................. 11 A. Establishing Student Cost of Attendance Budgets (COA) ..................................................... 11 B. Determining Expected Family Contribution (EFC) ................................................................ 11 C. Packaging Student Aid Funds ................................................................................................ 12 CHAPTER 2 – Eligibility Requirements .......................................................................................... 13 A. Overview of the Title IV Student Eligibility Requirements ................................................... 13 B. Criteria Collected on the FAFSA or through the Application Process................................... 15 C. Documentation of Citizenship or Immigration Status .......................................................... 15 a. Eligible Categories .......................................................................................................... 16 b. Ineligible Categories ...................................................................................................... 16 D. Citizenship -

Connect Connect Ollege Ollege Ions

CO LLEGE ONNECT I ONS Fall 2015 COLLEGE Winter 2015 ! Save C the Date Affording College/Cómo pagar la January 12 cIcu universidad Professional Development The 2016 editions of Affording College and Cómo pagar la ! ! Workshop ONNECT universidad, with information on ! CcIcu’s 2016 Professional Development (PD) inancial aid and how to pay for !Workshop for school guidance/college counselors, college, are now available in English !teachers, school administrators and community and Spanish. Included in this booklet !organizations will be held on Tuesday, January 12, are sections on how to apply for !2016, hosted by Pace University School of Education =inancial aid, the FAFSA, the !at Pace University/NYC Campus, in lower Expected Family Contribution (EFC), !Manhattan. ! inancial aid packages, grants, Independent college and university faculty, scholarships, work-study programs, admissions and =inancial aid professionals – and and loans, along with a list of more – will facilitate discussions and provide Internet resources and a college updates on =inancial aid and innovative programs. In campus locator map. Copies of each addition to a number of concurrent, small format, publication can be downloaded for T focused breakout sessions, the day will also feature free at www.nycolleges.org/get- substantive plenary sessions and an opportunity to more-resources/paying-college. network with cIcu member college and university admissions professionals during admissions speed- cIcu’s 8th Annual Latino College Fair ! dating sessions. The PD’s agenda will be updated on Saturday, November 21, 2015 at Fordham University, Rose Hill Campus. All the event registration page (link below) as sessions and speakers are con=irmed. -

Powerpoint Slides

1 2 3 4 5 NYSAC Thanks our Workshop Sponsor: Higher Education in the Age of Covid-19 A Presentation for the New York State Association of Counties Mary Beth Labate, CICU President October 1, 2020 Adelphi University • Albany College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences • Albany Law School • Albany Medical College • Alfred University • American Academy McAllister Institute • American Museum of Natural History, Richard Gilder Graduate School • Bank Street College of Education • Bard College • Barnard College • The Belanger School of Nursing • Boricua College • Brooklyn Law School • Canisius College • Cazenovia College • Clarkson University • Cochran School of Nursing • Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Watson School of Biological Sciences • Colgate University • College of Mount Saint Vincent • The College of New Rochelle • The College of Saint Rose • Columbia University • Concordia College • The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art • Cornell University • The Culinary Institute of America • Daemen College • Dominican College • D’Youville College • Elmira College • Excelsior College • Fei Tian College • Finger Lakes Health College of Nursing • Fordham University • Hamilton College • Hartwick College • Helene Fuld College of Nursing • Hilbert College • Hobart and William Smith Colleges • Hofstra University • Houghton College • Iona College100+ • Ithaca College private, • The Jewish Theological Seminarynot • Keuka-for College- • Theprofit King’s College • Le Moyne College • Long Island University • Manhattan College • Manhattan School -

List of Colleges and Universities in New York City from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

List of coleges and univer sit ies in New Yor k Cit y - Wikipedia1, 2 /t 1h8e/ 1f 2r ee encyclopedia List of colleges and universities in New York City From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia This is a list of colleges and universities entirely in, or with a campus in, New York City. The Ailey School (Alvin Ailey American Dance Crew) American Academy McAllister Institute American Academy of Dramatic Arts American Musical and Dramatic Academy Art Institute of New York City ASA College (http://www.asa.edu) Bank Street College of Education Bard College (Globalization and International Affairs Program) Barnard College (affiliated with Columbia University) Berkeley College Bethel Seminary of the East Boricua College Bramson ORT College Briarcliffe College - The Queens Center Brooklyn Law School Christie's Education Inc City University of New York (CUNY) (multiple campuses) Baruch College Borough of Manhattan Community College Brooklyn College Bronx Community College City College of New York Sophie Davis School of Biomedical Education CUNY Baccalaureate for Unique and Interdisciplinary Studies CUNY Graduate Center CUNY School of Professional Studies CUNY Graduate School of Journalism CUNY William E. Macaulay Honors College CUNY School of Law (at Queens College) College of Staten Island Hostos Community College Hunter College John Jay College of Criminal Justice Kingsborough Community College LaGuardia Community College Lehman College Medgar Evers College New York City College of Technology en. wikipedia. or g/ wiki/ List _of _coleges_and_univer -

Boricua College, Human Services

BRONX COMMUNITY COLLEGE OF THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK ARTICULATION AGREEMENT FORM A. Sending and Receiving Institutions Sending College: Bronx Community College of the City University of New York Department: Social Sciences Program: Human Services Degree: Associate in Applied Sciences Receiving College: Boricua College Department: Human Services Program: Human Services Degree: Bachelor of Science B. Admission Requirements for Senior College Program (e.g., minimum GPA, audition/portfolio): Application Procedures The academic year at Boricua is made up of three sessions, the Fall/Spring regular session of fifteen (15) weeks each and the summer session of eight (8) weeks. Students may begin their studies in September for the fall session and in January for the Spring session. The specific dates for each session are indicated in the Academic Calendar for the year. 1. Submit a completed Application Form, together with a non-refundable fee to the Admissions Department at one of the following locations: Manhattan - Audubon Terrace Campus 3755 Broadway (156 Street) New York, NY 10032 Attn: Ismael Sanchez - Admissions Director (212) 694-1000 ext. 675 Bronx Campus at Melrose Commons 890 Washington Avenue Bronx, NY 10451 Attn: Abraham Cruz - Vice President of Admissions and Enrollment Management (347) 964-8600 ext. 360 Brooklyn Campus - Northside 186 North 6th Street Brooklyn, NY 11211 Attn: Frank Serrano - Admissions Senior Officer (718) 782-2200 ext. 213 Brooklyn Campus – Graham 9 Graham Avenue Brooklyn, NY 11206 Attn: Aurea Morales (718) 963-4112 ext. 543 2. Contact all high schools, colleges and/or other post-secondary institutions previously attended, and request that an Official Academic Transcript and Financial Aid Transcript be forwarded directly to the Admissions Department. -

Mayor's Graduate Scholarship

MAYOR’S GRADUATE SCHOLARSHIP PROGRAM SCHOLARSHIP OFFERING GUIDE: ACADEMIC YEAR – FALL 2019 – SPRING 2020 MGSP SCHOLARSHIP OFFERING GUIDE COLLEGE/UNIVERSITY SCHOOL/DIVISION PAGE DESCRIPTION OF GUIDEBOOK 5 ADELPHI UNIVERSITY School of Social Work 6 ALFRED UNIVERSITY 7 BINGHAMTON UNIVERSITY Graduate Program 8 BORICUA COLLEGE Graduate Program 9 COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY Data Science Institute 10 COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY Institute of Social & Economic Research & Policy 11 COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY Mailman School of Public Health 12 COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY School of Social Work 13 CORNELL UNIVERSITY School of Industrial & Labor Relations 14 CUNY/BARUCH COLLEGE Austin W. Marxe School of Public and International Affairs 15 CUNY/BARUCH COLLEGE Zicklin School of Business 16 CUNY (NEW) Graduate School of Public Health and Health Policy 17 CUNY (NEW) The Graduate Center 18 FORDHAM UNIVERSITY School of Law 19 2 COLLEGE/UNIVERSITY SCHOOL/DIVISION PAGE FORDHAM UNIVERSITY School of Social Service 20 LONG ISLAND UNIVERSITY Brentwood and Riverhead 21 LONG ISLAND UNIVERSITY Brooklyn Campus 22 LONG ISLAND UNIVERSITY Post Campus 23 MANHATTAN COLLEGE Graduate Education 24-28 METROPOLITAN COLLEGE OF NEW YORK 29 MONROE COLLEGE King Graduate School 30 NEW JERSEY INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY 31-32 NEW YORK INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY 33-35 NEW YORK LAW SCHOOL 36 NEW YORK UNIVERSITY Center for Urban Science + Progress 37 NEW YORK UNIVERSITY Robert F. Wagner Graduate School of Public Service 38 NEW YORK UNIVERSITY School of Professional Studies 39-40 NEW YORK UNIVERSITY Silver School of Social -

Arthur O. Eve Higher Education in a Post-Secondary Institution

Is HEOP for you? If interested, please contact the Directors of Admissions or the Arthur O. Eve What is expected of HEOP Students? Higher Education Opportunity Program (HEOP) Office, at one of our four convenient locations: As a HEOP student you MUST: 1) respect others; 2) conduct oneself in a ARTHUR O. EVE BRONX CAMPUS manner befitting of a College student; 3) HIGHER EDUCATION regularly attend classes and 4) maintain 890 Washington Avenue Satisfactory Academic Progress (SAP). Bronx, NY 10451 OPPORTUNITY PROGRAM: SAP is achieved by maintaining (347) 964-8600, Ext. 360 2013-14 GUIDELINES satisfactory attendance in all courses, Mr. Abraham Cruz, VP of Admissions participating in and completing all assignments as well as abiding by the MANHATTAN CAMPUS 3755 Broadway standards set by both local and federal New York, NY 10032 HEOP agencies for Satisfactory Academic HEOP (212) 694-1000 Ext. 675 Progress and Program Pursuit (PLEASE Mr. Ismael Sanchez, Director of Admissions SEE THE STUDENT HANDBOOK). BROOKLYN CAMPUS - GRAHAM 9 Graham Avenue Compliance with Program Regulations Brooklyn, NY 11206 (718) 963-4112 Ext. 543 As a HEOP student you will be Ms. Aurea Morales, Director of Admissions REQUIRED to: 1) Meet with your Retention Counselor on a weekly basis as BROOKLYN CAMPUS - scheduled; 2) report to tutorials once a NORTHSIDE week during each academic cycle - 187 North 6 schedules are available at each of the Brooklyn, NY 11211 HEOP offices, through your educational (718) 782-2200 Ext. 210 facilitators, department chairperson or Ms. Miriam Pfeffer, Director of Admissions by postings on the bulletin boards located throughout the college; 3) attend HEOP Office informative general meeting established (Division of the Student Academic by the program Director. -

Hispanic-Serving Institutions

HISPANIC-SERVING INSTITUTIONS (HSIs) AND HSIs WITH HISPANIC-SERVING AGRICULTURAL COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES (HSACU) CERTIFICATION United States Department KEY STATE TOTAL STATE WITH NIFA-FUNDED SITE(S) of Agriculture OF HSIS & HSACUS 61 STATE WITH SITE(S) National CURRENT CURRENT Institute of NIFA-FUNDED HSIs 1 1 NIFA-FUNDED HSACUs STATE WITHOUT SITE(S) Food and Agriculture 5 0 0 FACT: 3 1 0 0 0 0 OF 356 TOTAL SITES, 18 38 SITES CURRENTLY RECEIVE 0 0 NIFA FUNDING 3 0 0 13 1 112 7 2 0 0 0 8 4 7 0 0 4 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 10 1 1 23 1 3 66 10 5 20 1 1 61 1 1 HISPANIC-SERVING INSTITUTIONS (HSIs) AND HSIs WITH HISPANIC-SERVING AGRICULTURAL COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES (HSACU) CERTIFICAtion — current nifA-FUNDED SITES IN BOLD ARIZONA Cuyamaca College San Joaquin Delta College* Trinity International University, New Mexico Institute Caribbean University, Bayamon Universidad Central Del Caribe Remington College, Dallas Campus Arizona Western College Cypress College San Jose City College Florida of Mining and Technology* Caribbean University, Carolina Universidad Del Este Remington College, Central Arizona College* East Los Angeles College Santa Ana College* Valencia College New Mexico Junior College Caribbean University, Ponce Universidad Del Turabo* Fort Worth Campus Cochise College El Camino College, Santa Barbara City College ILLINOIS New Mexico Military Institute Caribbean University, Vega Baja Universidad Metropolitana* Remington College, Houston Campus Estrella Mountain Community Compton Center Santa Monica College City Colleges of Chicago, New Mexico -

Reproductions Supplied by EDRS Are the Best That Can Be Made from the Original Document

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 472 315 HE 035 588 TITLE Affording College: Financial Aid, New York's 100 Private Colleges and Universities, Internet Resources. 2002 Edition. INSTITUTION Commission on Independent Colleges and Universities of the State of New York, New York. REPORT NO Vol-4 PUB DATE 2002-00-00 NOTE 20p.; Published annually. PUB TYPE Guides Non-Classroom (055) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *College Applicants; Grants; *Paying for College; *Private Colleges; *Student Financial Aid; Student Loan Programs IDENTIFIERS *Affordability; *New York ABSTRACT This handbook explains the "how to's" of financial aid, focusing on private colleges in New York state. The first section discusses financial aid, explaining that a student who needs financial aid is very likely to receive it. The aid process is outlined, step by step. This section also explains the types of federal and other aid available and tells the student what will happen after the forms are filed. A section on Internet resources tells the student where to look on the Web to download financial aid forms and to find information about applying. The "Campus Directory" section contains information about the more than 100 private colleges in New York, grouped by region, and provides admissions office addresses and other contact information. A calendar of financial aid deadlines is designed to help the student map a strategy for finding financial aid and comparing institutions. (SLD) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. Financial Aid New York's 100+ Private Colleges and Universities Internet Resources ey JS ..-=1:111t), V,91: PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE AND U.S. -

This Chart in .PDF Format

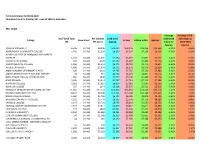

Estimated Library Aid 2019-2020 Education Law 273, Chapter 917, Laws of 1990 as amended 3R's CCDA %change %change 2018- 2017-2018 Total Per Student 2018-2019 2019-2020 2019 Approp College Base Grant Ed Law Ed Law w/HH Approp. FTE FTE Grant Approp EdLaw to 2019-2020 Approp Approp ADELPHI UNIVERSITY 8,506 $4,400 $8,846 $12,094 $13,246 $13,246 $12,530 -5.41% 3.60% ADIRONDACK COMMUNITY COLLEGE 2,783 $4,400 $2,894 $6,879 $7,294 $7,294 $6,900 -5.41% 0.30% ALBANY COLLEGE OF PHARMACY AND HEALTH SCIENCES 1,434 $4,400 $1,491 $5,584 $5,891 $5,891 $5,572 -5.41% -0.20% ALBANY LAW SCHOOL 622 $4,400 $647 $5,152 $5,047 $5,449 $5,154 -5.41% 0.05% ALBANY MEDICAL COLLEGE 1,260 $4,400 $1,310 $5,372 $5,710 $5,710 $5,401 -5.41% 0.54% ALFRED UNIVERSITY 1,806 $4,400 $1,878 $5,943 $6,278 $6,278 $5,938 -5.41% -0.08% AMER ACADEMY OF DRAMATIC ARTS 326 $4,400 $339 $4,465 $4,739 $4,739 $4,483 -5.41% 0.39% AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY 50 $4,400 $51 $4,204 $4,451 $4,451 $4,210 -5.41% 0.14% BANK STREET COLLEGE OF EDUCATION 806 $4,400 $838 $5,152 $5,238 $5,449 $5,154 -5.41% 0.05% BARD COLLEGE 3,185 $4,400 $3,313 $7,307 $7,713 $7,713 $7,296 -5.41% -0.16% BARNARD COLLEGE 2,584 $4,400 $2,687 $6,673 $7,087 $7,087 $6,704 -5.41% 0.46% BORICUA COLLEGE 937 $4,400 $974 $5,398 $5,374 $5,709 $5,400 -5.41% 0.05% BOROUGH OF MANHATTAN COMM COLLEGE 21,302 $4,400 $22,154 $24,856 $26,554 $26,554 $25,118 -5.41% 1.05% BRONX COMMUNITY COLLEGE 8,412 $4,400 $8,748 $12,309 $13,148 $13,148 $12,437 -5.41% 1.04% BROOKLYN LAW SCHOOL 1,640 $4,400 $1,706 $6,122 $6,106 $6,475 $6,125 -5.41% 0.05% -

New York Opportunity Programs What Is an Opportunity Program?

New York Opportunity Programs What is an opportunity program? An opportunity program is a special program offered at colleges and universities to help support students academically and financially who might otherwise be unable to attend college due to academic or financial circumstances Which schools offer opportunity programs? Opportunity programs are offered at all CUNY’s, most SUNY’s, and some private schools in New York. The programs are basically the same but may have different names: CUNY (4 Yr) = SEEK CUNY (2 Yr) = College Discovery SUNY=EOP Private schools in New York= HEOP What are the benefits of these programs? Academic, career, tutoring, and personal advising Financial support for books and tuition (depending on the program) A special summer program to help prepare you for the college experience! Am I eligible to apply to an opportunity program? In order to apply for an opportunity program you must be BOTH academically AND financially eligible: Academic Eligibility: You must have a lower GPA and/or SAT score than the schools normally require to be admitted. Check out the school requirements on their website or on handouts in the college office. You must fall within BOTH the SAT and GPA range in order to be academically eligible. Financial Eligibility: To be considered financially eligible, your parent/guardians income must be at or less than the amounts shown below based on how many people are living in your household. Do NOT count the income of anyone else living in your household who may be working such as yourself, siblings, grandparents etc. See your counselor for help! Household Size Total Annual Income 1 $21,978 2 $29,637 3 $37,296 4 $44,955 5 $52,614 6 $60,273 7 $67,951 8 $75,647 *Plus $7,696 for each additional household member in excess of eight How do I apply? For most opportunity programs, you simply must answer YES on the application when asked if you would like to be considered for them. -

New York's 100+ Private Colleges and Universities Nycolleges.Org

New York's 100+ Private Colleges and Universities nycolleges.org 1 3 Potsdam 2 North Country Colleges are listed in each region of the state alphabetically by College Name. The City in which each college is located is in italics. Degrees ofered appear in parentheses with bachelor’s degrees indicated by (B) and associate degrees Central New York indicated by (A). Campuses that ofer graduate degrees (master’s, doctorate, or frst professional) are indicated by (G) 1. Cazenovia College 800.654.3210 4 KEY: Cazenovia (A,B) cazenovia.edu 5 College Name Phone 2. Colgate University 315.228.7401 3 4 5 6 16 City (Degrees Ofered) Web Hamilton (B,G) colgate.edu 3 4 6 7 8 9 *Graduate-only campus 3. Le Moyne College 800.333.4733 1 2 10 Syracuse (B,G) lemoyne.edu 11 Western New York 2 Utica 4. Pomeroy College of Nursing 315.470.7481 8 Rochester 1 15 13 4 Syracuse at Crouse Hospital crouse.org/nursing 5 1 Mohawk 1. Alfred University 800.541.9229 Syracuse (A) 7 3 Finger Lakes 1 Alfred (B, G) alfred.edu Geneva Central Valley 14 10 Bufalo 2 Troy 2 5. St. Joseph’s College of 315.448.5040 7 3 2. Canisius College 800.843.1517 Nursing at St. Joseph’s Health sjhcon.edu 11 5 Albany Bufalo (B,G) canisius.edu Syracuse (A) 6 2 Capital 3. Daemen College 800.462.7652 7 6. Syracuse University 315.443.3611 Western Ithaca District 8 Amherst (B,G) daemen.edu Syracuse (A,B,G) syracuse.edu 6 1 9 4.