The Cultural Geographer's Interest in Regions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spatial Dimensions of Conflict-Induced Internally Displaced Population in the Puttalam District of Sri Lanka from 1980 to 2012 Deepthi Lekani Waidyasekera

University of North Dakota UND Scholarly Commons Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Senior Projects 12-1-2012 Spatial Dimensions of Conflict-Induced Internally Displaced Population in the Puttalam District of Sri Lanka from 1980 to 2012 Deepthi Lekani Waidyasekera Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.und.edu/theses Recommended Citation Waidyasekera, Deepthi Lekani, "Spatial Dimensions of Conflict-Induced Internally Displaced Population in the Puttalam District of Sri Lanka from 1980 to 2012" (2012). Theses and Dissertations. 668. https://commons.und.edu/theses/668 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, and Senior Projects at UND Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UND Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SPATIAL DIMENSIONS OF CONFLICT-INDUCED INTERNALLY DISPLACED POPULATION IN THE PUTTALAM DISTRICT OF SRI LANKA FROM 1980 TO 2012 by Deepthi Lekani Waidyasekera Bachelor of Arts, University of Sri Jayawardanapura,, Sri Lanka, 1986 Master of Science, University of Moratuwa, Sri Lanka, 2001 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of North Dakota In partial fulfilment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Arts Grand Forks, North Dakota December 2012 Copyright 2012 Deepthi Lekani Waidyasekera ii PERMISSION Title Spatial Dimensions of Conflict-Induced Internally Displaced Population in the Puttalam District of Sri Lanka from 1980 to 2012 Department Geography Degree Master of Arts In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a graduate degree from the University of North Dakota, I agree that the library of the University shall make it freely available for inspection. -

Newsletter Supporting Communities in Need

NEWSLETTER ICRC JULY-SEPTEMBER 2014 SUPPORTING COMMUNITIES IN NEED Economic security and water and sanitation for the vulnerable Dear Reader, they could reduce the immense economic This year, the ICRC started a Community Conflicts destroy livelihoods and hardships and poverty under which they Based Livelihood Support Programme infrastructure which provide water and and their families are living at present” (para (CBLSP) to support vulnerable communities sanitation to communities. Throughout 5.112). in the Mullaitivu and Kilinochchi districts the world, the ICRC strives to enable access to establish or consolidate an income to clean water and sanitation and ensure The ICRC’s response during the recovery generating activity. economic security for people affected by phase to those made vulnerable by the conflict so they can either restore or start a conflict was the piloting of a Micro Economic The ICRC’s economic security programmes livelihood. Initiatives (MEI) programme for women- are closely linked to its water and sanitation headed households, people with disabilities initiatives. In Sri Lanka today, the ICRC supports and extremely vulnerable households in vulnerable households and communities In Sri Lanka, the ICRC restores wells the Vavuniya district in 2011. The MEI is in the former conflict areas to become contaminated as a result of monsoonal a programme in which each beneficiary economically independent through flooding, and renovates and builds pipe identifies and designs the livelihood sustainable income generation activities and networks, overhead water tanks, and for which he or she needs assistance to provides them clean water and sanitation by toilets in rural communities for returnee implement, thereby employing a bottom- cleaning wells and repairing or constructing populations to have access to clean water up needs-based approach. -

Sri Lanka – Tamils – Eastern Province – Batticaloa – Colombo

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: LKA34481 Country: Sri Lanka Date: 11 March 2009 Keywords: Sri Lanka – Tamils – Eastern Province – Batticaloa – Colombo – International Business Systems Institute – Education system – Sri Lankan Army-Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam conflict – Risk of arrest This response was prepared by the Research & Information Services Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. This research response may not, under any circumstance, be cited in a decision or any other document. Anyone wishing to use this information may only cite the primary source material contained herein. Questions 1. Please provide information on the International Business Systems Institute in Kaluvanchikkudy. 2. Is it likely that someone would attain a high school or higher education qualification in Sri Lanka without learning a language other than Tamil? 3. Please provide an overview/timeline of relevant events in the Eastern Province of Sri Lanka from 1986 to 2004, with particular reference to the Sri Lankan Army (SLA)-Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) conflict. 4. What is the current situation and risk of arrest for male Tamils in Batticaloa and Colombo? RESPONSE 1. Please provide information on the International Business Systems Institute in Kaluvanchikkudy. Note: Kaluvanchikkudy is also transliterated as Kaluwanchikudy is some sources. No references could be located to the International Business Systems Institute in Kaluvanchikkudy. The Education Guide Sri Lanka website maintains a list of the “Training Institutes Registered under the Ministry of Skills Development, Vocational and Tertiary Education”, and among these is ‘International Business System Overseas (Pvt) Ltd’ (IBS). -

Multi-Decadal Forest-Cover Dynamics in the Tropical Realm: Past Trends and Policy Insights for Forest Conservation in Dry Zone of Sri Lanka

Article Multi-Decadal Forest-Cover Dynamics in the Tropical Realm: Past Trends and Policy Insights for Forest Conservation in Dry Zone of Sri Lanka Manjula Ranagalage 1,2,* , M. H. J. P. Gunarathna 3 , Thilina D. Surasinghe 4 , Dmslb Dissanayake 2 , Matamyo Simwanda 5 , Yuji Murayama 1 , Takehiro Morimoto 1 , Darius Phiri 5 , Vincent R. Nyirenda 6 , K. T. Premakantha 7 and Anura Sathurusinghe 7 1 Faculty of Life and Environmental Sciences, University of Tsukuba, 1-1-1, Tennodai, Tsukuba, Ibaraki 305-8572, Japan; [email protected] (Y.M.); [email protected] (T.M.) 2 Department of Environmental Management, Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities, Rajarata University of Sri Lanka, Mihintale 50300, Sri Lanka; [email protected] 3 Department of Agricultural Engineering and Soil Science, Faculty of Agriculture, Rajarata University of Sri Lanka, Anuradhapura 50000, Sri Lanka; [email protected] 4 Department of Biological Sciences, Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, MA 02325, USA; [email protected] 5 Department of Plant and Environmental Sciences, School of Natural Resources, Copperbelt University, P.O. Box 21692, Kitwe 10101, Zambia; [email protected] (M.S.); [email protected] (D.P.) 6 Department of Zoology and Aquatic Sciences, School of Natural Resources, Copperbelt University, Kitwe 10101, Zambia; [email protected] 7 Forest Department, Ministry of Environment and Wildlife Resources, 82, Rajamalwatta Road, Battaramulla 10120, Sri Lanka; [email protected] (K.T.P.); [email protected] (A.S.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 30 June 2020; Accepted: 28 July 2020; Published: 1 August 2020 Abstract: Forest-cover change has become an important topic in global biodiversity conservation in recent decades because of the high rates of forest loss in different parts of the world, especially in the tropical region. -

Batticaloa District

LAND USE PLAN BATTICALOA DISTRICT 2016 Land Use Policy Planning Department No.31 Pathiba Road, Colombo 05. Tel.0112 500338,Fax: 0112368718 1 E-mail: [email protected] Secretary’s Message Lessons Learnt and Reconciliation Commission (LLRC) made several recommendations for the Northern and Eastern Provinces of Sri Lanka so as to address the issues faced by the people in those areas due to the civil war. The responsibility of implementing some of these recommendations was assigned to the different institutions coming under the purview of the Ministry of Lands i.e. Land Commissioner General Department, Land Settlement Department, Survey General Department and Land Use Policy Planning Department. One of The recommendations made by the LLRC was to prepare Land Use Plans for the Districts in the Northern and Eastern Provinces. This responsibility assigned to the Land Use Policy Planning Department. The task was completed by May 2016. I would like to thank all the National Level Experts, District Secretary and Divisional Secretaries in Batticaloa District and Assistant Director (District Land Use.). Batticaloa and the district staff who assisted in preparing this plan. I also would like to thank Director General of the Land Use Policy Planning Department and the staff at the Head Office their continuous guiding given to complete this important task. I have great pleasure in presenting the Land Use Plan for the Batticaloa district. Dr. I.H.K. Mahanama Secretary, Ministry of Lands 2 Director General’s Message I have great pleasure in presenting the Land Use Plan for the Batticaloa District prepared by the officers of the Land Use Policy Planning Department. -

Dinesh Hemachandra Scientist /Geologist National Building

Dinesh Hemachandra Scientist /Geologist National Building Research Organisation Ministry of Disaster Management Sri Lanka Visiting Researcher 2010 – ADRC, Kobe Country Presentation – Sri Lanka Geographical and Historical Background of Sri Lanka Government of Sri Lanka Climate conditions Natural Disasters and Mitigation of Landslide hazard Disaster Management in Sri Lanka My Institute –National Building Research Organisation Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR )activities The Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka (Formerly known as Ceylon) Geographical situation Geographical Coordinate Longitude 79° 42. to 81° 52 east Latitude 5° 55. to 9° 50. north, The maximum north- south length of (formerly known the island is 435 km and its greatest width is 225 km The Island (including adjacent small islands) covers a land area of 65,610 sq. km. The Bay of Bengal lies to its north and east and the Arabian Sea to its West. Sri Lanka is separated from India by the gulf of Manna and the Palk Strait Historical Background – Kings Rural Period Recent excavations show that even during the Neolithic Age, there were food gatherers and rice cultivators in Sri Lanka documented history began with the arrival of the Aryans from North India. Anuradhapura grew into a powerful kingdom under the rule of king Pandukabhaya. According to traditional history he is accepted as the founder of Anuradhapura. The Aryans introduced the use of iron and an advanced form of agriculture and irrigation. They also introduced the art of government In the mid 2nd century B.C. a large part of north Sri Lanka came under the rule of an invader from South India. -

Polonnaruwa Development Plan 2018-2030

POLONNARUWA URBAN DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2018-2030 VOLUME I Urban Development Authority District Office Polonnaruwa 2018-2030 i Polonnaruwa 2018-2030, UDA Polonnaruwa Development Plan 2018-2030 POLONNARUWA URBAN DEVELOPMENT PLAN VOLUME I BACKGROUND INFORMATION/ PLANNING PROCESS/ DETAIL ANALYSIS /PLANNING FRAMEWORK/ THE PLAN Urban Development Authority District Office Polonnaruwa 2018-2030 ii Polonnaruwa 2018-2030, UDA Polonnaruwa Development Plan 2018-2030 DOCUMENT INFORMATION Report title : Polonnaruwa Development Plan Locational Boundary (Declared area) : Polonnaruwa MC (18 GN) and Part of Polonnaruwa PS(15 GN) Gazette No : Client/ Stakeholder (shortly) : Local Residents, Relevent Institutions and Commuters Commuters : Submission date :15.12.2018 Document status (Final) & Date of issued: Author UDA Polonnaruwa District Office Document Submission Details Version No Details Date of Submission Approved for Issue 1 Draft 2 Draft This document is issued for the party which commissioned it and for specific purposes connected with the above-captioned project only. It should not be relied upon by any other party or used for any other purpose. We accept no responsibility for the consequences of this document being relied upon by any other party, or being used for any other purpose, or containing any error or omission which is due to an error or omission in data supplied to us by other parties. This document contains confidential information and proprietary intellectual property. It should not be shown to other parties without consent from the party -

Annual Performance Report of the District Secretariat

ANNUAL PERFORMANCE REPORT FOR THE YEAR 2019, TRINCOMALEE 뷒ස්ත්රි槊 ලේක කායාලය,ක臊ල臊ය,ි槔ණාමලය khtl;lr; nrayfk;, jpUNfhzkiy District Secretariat, Kachcheri, Trincomalee වාික කායස්ත්ාධන වාතාව tUlhe;j nraw;jpwd; mwpf;if ANNUAL PERFORMANCE REPORT 2019 0 ANNUAL PERFORMANCE REPORT FOR THE YEAR 2019, TRINCOMALEE Annual Performance Report for the year 2019 District Secretariat, Trincomalee Expenditure Head No 271 Contents Page Chapter 01 - Institutional Profile ………………………………………………………… 2-10 Chapter 02 – Progress and the Future Outlook …………………………………... 11 Chapter 03 - Overall Financial Performance for the Year ……………….……. 12-41 Chapter 04- Performance of the achieving Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) ………………………………………………. 42-45 Chapter 05 - Human Resource Profile ………………………………………………… 46-48 Chapter 06– Compliance Report ………………………………………………………… 49-54 1 ANNUAL PERFORMANCE REPORT FOR THE YEAR 2019, TRINCOMALEE Chapter 01 - Institutional Profile 1.1. Introduction Trincomalee District - A Glimpse The Boundary Trincomalee, a picturesque city with a natural 2arbor, scenic beauty, and military, commercial and historical importance, is situated in the eastern coast of Sri Lanka. Trincomalee District is boarded with Mulathivu District in North, Anuradhapura District in West and Polonnaruwa and Batticaloa Districts in the South. The History The history of Trincomalee goes back to a time of immemorial. The Mahavamsa & Chulavamsa, the two great chronicles, mention present Trincomalee as “Gokanna” , Gokarna, and “Gonagamaka” During the Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa periods of island’s history. The Administration The Trincomalee District located in the center of Eastern Province covering an area of 2,727 square kilometers. The district is divided into 11 Divisional Secretary’s Divisions for administrative purpose. The DS Divisions are further sub-divided into 230 Grama Niladhari Divisions. -

Trincomalee District – 2007

BASIC POPULATION INFORMATION ON TRINCOMALEE DISTRICT – 2007 Preliminary Report Based on Special Enumeration – 2007 Department of Census and Statistics October 2007 ISBN 978-955-577-616-5 Foreword The Department of Census and Statistics (DCS), carried out a special enumeration in Eastern province and in Jaffna district in Northern province. The objective of this enumeration is to provide the necessary basic information needed to formulate development programmes and relief activities for the people. This preliminary publication for Trincomalee district has been compiled from the reports obtained from the District based on summaries prepared by enumerators and supervisors. A final detailed information will be disseminated after the computer processing of questionnaires. This preliminary release gives some basic information for Trincomalee district, such as population by divisional secretary’s division, urban/rural population, sex, age (under 18 years and 18 years and over) and ethnicity. Data on displaced persons due to conflict or tsunami are also included. Some important information which is useful for regional level planning purposes are given by Grama Niladhari Divisions. This enumeration is based on the usual residents of households in the district. These figures should be regarded as provisional. I wish to express my sincere thanks to the staff of the department and all other government officials and others who worked with dedication and diligence for the successful completion of the enumeration. I am also grateful to the general public for extending their fullest co‐operation in this important undertaking. This publication has been prepared by Population Census Division of this Department. D.B.P. Suranjana Vidyaratne Director General of Census and Statistics 10th October 2007 Department of Census and Statistics, 15/12, Maitland Crescent, Colombo 7. -

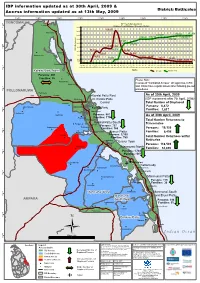

IDP Numbers and Access 30042009 GA Figures

IDP information updated as at 30th April, 2009 & District: Batticaloa Access information updated as at 13th May, 2009 81°15'0"E 81°20'0"E 81°25'0"E 81°30'0"E 81°35'0"E 81°40'0"E 81°45'0"E 81°50'0"E 81°55'0"E TRINCOMALEE (! IDP Trend - Batticaloa District Verugal Returnees Trend - Batticaloa / Trincomalee Districts 8°15'0"N 180,000 159,355 (! 160,000 Kathiravely 136,084 137,659 140,000 127,837 119,527 120,742 136,555 120,000 132,728 97,405 100,000 108,784 72,986 80,000 81,312 8°10'0"N IDPs/Returnees 60,272 68,971 60,000 51,901 (! Vaharai (! 52,685 38,230 Kaddumurivu 40,000 38,121 26,484 24,987 17,600 18,171 12,551 20,000 8,020 1,140 8,543 6,872 (! 0 Panichankerny Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Jan Feb Mar Apr May June July Aug Sept Oct Nov Dec Jan Feb Mar Apr 2006 2006 2006 2006 2006 2006 2006 2006 2006 2007 2007 2007 2007 2007 2007 2007 2007 2007 2007 2007 2007 2008 2008 2008 2008 2008 2008 2008 2008 2008 2008 2008 2008 2009 2009 2009 2009 8°5'0"N Months IDP Trend Returnees' Trend Koralai Pattu North A 1 Persons: 201 5 Families: 55 (! Please Note: Kirimichchai In areas of "Controlled Access" UN agencies, ICRC Mankerny (! and INGO have regular access after following pre-set procedures. -

Ward Map of Walapane Pradeshiya Sabha - Nuwara Eliya District Ref.T No : NDC / 06 / 08

Section 2 of 2 sections Ward Map of Walapane Pradeshiya Sabha - Nuwara Eliya District Ref.t No : NDC / 06 / 08 Ward No GN No GN Name Ward No GN No GN Name Walapane PS 513 Pannala 514 C Mulhalkele 515 B Walapane 513 A Serupitiya 12 515 C Kandegame 513 B Sarasunthenna 515 D Wathumulla 1 513 C Wewakele 515 E Maha Uva $ 513 D Ihala Pannala 13 516 B Egodakande 513 E Mylagastenna 516 D Mahapathana 514 A Naranthalawe 516 C Werellapathana 519 E Morangatenna 517 B Thibbatugoda South 517 C Rambuke 521 C Theripehe 2 14 517 D Arampitiya 521 D Mallagama 524 B Gorandiyagolla 521 E Dulana 524 D Dambare 518 B Udamadura North 524 E Nildandahinna Walapane Pradeshiya Sabha 518 C Galkadawala 518 Udamadura Ward No Ward Name 521 Bolagandawela 518 A Kosgolla 3 15 521 A Hegasulla 523 AmbanElla 1 Pannala 523 B Wewatenna 2 Theripeha 0 521 B Ambagahathenna 0 518 D Yatimadura 0 3 Udamadura North 5 521 F Helagama 518 E Thunhitiyawa 1 4 Kalaganwatta 2 519 Kalaganwatta 518 F Demata Arawa 5 Thibbatugoda 519 A Udawela 523 A Hegama 16 6 Kumbalgamuwa 519 B Yombuweltenna 524 Denambure 7 Liyanwala 4 519 C Galketiwela 524 A Dambagolla 524 C Purankumbura 8 Landupita 519 D Hapugahepitiya 525 B Karandagolla 9 Padiyapelella 519 F Ellekumbura 527 Madulla North 10 Kurudu Oya 519 G Mugunagahapitiya 527 A Madulla South 17 11 Highforest 515 Batagolla 527 B Morahela 12 Walapane 515 A Manelwala 527 C Kandeyaya 13 Mahauva 516 Ketakandura 528 E Rupaha East 14 Nildandahinna 5 528 F Mathatilla 516 A Kendagolla 18 15 Udamadura 531 Ambaliyadda 517 Thibbatugoda 531 A Embulampaha 16 Yatimadura -

Post-Tsunami Redevelopment and the Cultural Sites of the Maritime Provinces in Sri Lanka

Pali Wijeratne Post-Tsunami Redevelopment and the Cultural Sites of the Maritime Provinces in Sri Lanka Introduction floods due to heavy monsoon rains, earth slips and land- slides and occasional gale force winds caused by depres- Many a scholar or traveller in the past described Sri Lanka sions and cyclonic effects in either the Bay of Bengal or as »the Pearl of the Indian Ocean« for its scenic beauty and the Arabian Sea. Sri Lanka is not located in the accepted nature’s gifts, the golden beaches, the cultural riches and seismic region and hence the affects of earthquakes or the mild weather. On that fateful day of 26 December 2004, tsunamis are unknown to the people. The word ›tsunami‹ within a matter of two hours, this resplendent island was was not in the vocabulary of the majority of Sri Lankans reduced to a »Tear Drop in the Indian Ocean.« The Indian until disaster struck on that fateful day. Ocean tsunami waves following the great earthquake off The great historical chronicle »Mahavamsa« describes the coast of Sumatra in the Republic of Indonesia swept the history of Sri Lanka from the 5th c. B. C. This chronicle through most of the maritime provinces of Sri Lanka, reports an incident in the 2nd c. B. C. when »the sea-gods causing unprecedented damage to life and property. made the sea overflow the land« in the early kingdom of There was no Sri Lankan who did not have a friend or Kelaniya, north of Colombo. It is to be noted that, by acci- relation affected by this catastrophe.