150526Reynoldsjbstatement.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report and Accounts 2019

IMPERIAL BRANDS PLC BRANDS IMPERIAL ANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS 2019 ACCOUNTS AND REPORT ANNUAL ANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS 2019 OUR PURPOSE WE CAN I OWN Our purpose is to create something Everything See it, seize it, is possible, make it happen better for the world’s smokers with together we win our portfolio of high quality next generation and tobacco products. In doing so we are transforming WE SURPRISE I AM our business and strengthening New thinking, My contribution new actions, counts, think free, our sustainability and value creation. exceed what’s speak free, act possible with integrity OUR VALUES Our values express who we are and WE ENJOY I ENGAGE capture the behaviours we expect Thrive on Listen, challenge, share, make from everyone who works for us. make it fun connections The following table constitutes our Non-Financial Information Statement in compliance with Sections 414CA and 414CB of the Companies Act 2006. The information listed is incorporated by cross-reference. Additional Non-Financial Information is also available on our website www.imperialbrands.com. Policies and standards which Information necessary to understand our business Page Reporting requirement govern our approach1 and its impact, policy due diligence and outcomes reference Environmental matters • Occupational health, safety and Environmental targets 21 environmental policy and framework • Sustainable tobacco programme International management systems 21 Climate and energy 21 Reducing waste 19 Sustainable tobacco supply 20 Supporting wood sustainability -

Current Status of the Reduced Propensity Ignition Cigarette Program in Hawaii

Hawaii State Fire Council Current Status of the Reduced Propensity Ignition Cigarette Program in Hawaii Submitted to The Twenty-Eighth State Legislature Regular Session June 2015 2014 Reduced Ignition Propensity Cigarette Report to the Hawaii State Legislature Table of Contents Executive Summary .…………………………………………………………………….... 4 Purpose ..………………………………………………………………………....................4 Mission of the State Fire Council………………………………………………………......4 Smoking-Material Fire Facts……………………………………………………….............5 Reduced Ignition Propensity Cigarettes (RIPC) Defined……………………………......6 RIPC Regulatory History…………………………………………………………………….7 RIPC Review for Hawaii…………………………………………………………………….9 RIPC Accomplishments in Hawaii (January 1 to June 30, 2014)……………………..10 RIPC Future Considerations……………………………………………………………....14 Conclusion………………………………………………………………………….............15 Bibliography…………………………………………………………………………………17 Appendices Appendix A: All Cigarette Fires (State of Hawaii) with Property and Contents Loss Related to Cigarettes 2003 to 2013………………………………………………………18 Appendix B: Building Fires Caused by Cigarettes (State of Hawaii) with Property and Contents Loss 2003 to 2013………………………………………………………………19 Appendix C: Cigarette Related Building Fires 2003 to 2013…………………………..20 Appendix D: Injuries/Fatalities Due To Cigarette Fire 2003 to 2013 ………………....21 Appendix E: HRS 132C……………………………………………………………...........22 Appendix F: Estimated RIPC Budget 2014-2016………………………………...........32 Appendix G: List of RIPC Brands Being Sold in Hawaii………………………………..33 2 2014 -

Directory for Cigarettes and Roll-Your-Own Tobacco

DEPARTMENT OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL STATE OF HAWAI‘I DIRECTORY FOR CIGARETTES AND ROLL-YOUR-OWN TOBACCO of (Available at: http://ag.hawaii.gov/cjd/tobacco-enforcement-unit/) Certified Tobacco Product Manufacturers Their Brands and Brand Families DEPARTMENT OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL TOBACCO ENFORCEMENT UNIT 425 QUEEN STREET HONOLULU, HAWAI‘I 96813 (808) 586-1203 INDEX I. Directory: Cigarettes and Roll-Your-Own Tobacco Page 1. INTRODUCTION 3 2. DEFINITIONS 3 3. NOTICES 5 II. Update Summary For June 1, 2018 Posting * III. Alphabetical Brand List IV. Compliant Participating Manufacturers List V. Compliant Non-Participating Manufacturers List Posted: June 1, 2018 (updated most recent 9/5/2018) 2 1. INTRODUCTION Pursuant to Haw. Rev. Stat. §245-22.5(a), beginning December 1, 2003, it shall be unlawful for an entity (1) to affix a stamp to a package or other container of cigarettes belonging to a tobacco product manufacturer or brand family not included in this directory, or (2) to import, sell, offer, keep, store, acquire, transport, distribute, receive, or possess for sale or distribution cigarettes1 belonging to a tobacco product manufacturer or brand family not included in this directory. Pursuant to §245-22.5(b), any entity that knowingly violates subsection (a) shall be guilty of a class C felony. Pursuant to Haw. Rev. Stat. §§245-40 and 245-41, any cigarettes unlawfully possessed, kept, stored, acquired, transported, or sold in violation of Haw. Rev. Stat. §245-22.5 may be ordered forfeited pursuant to Haw. Rev. Stat., Chapter 712A. In addition, the attorney general may apply for a temporary or permanent injunction restraining any person from violating or continuing to violate Haw. -

Current Directory

Current Directory Manufacturer Manufacturer Brand Brand Brand Style Descriptors Brand Style Descriptors Cheyenne International, LLC (NPM) Grand River Enterprises Six Nations, Ltd. (NPM) Aura Seneca Menthol Glen Kings Box Blue 100s Box Radiant Gold Kings Box Blue 100s Soft Pack Robust Red Kings Box Blue 72s Slide Box Sky Blue Kings Box Blue King Size Box Blue King Size Soft Pack Cheyenne Chill King Size Box Gold 100 Box Extra Smooth Menthol 100s Box Gold King Box Extra Smooth Menthol 100s Soft Pack Menthol 100 Box Full Flavor 100s Box Menthol King Box Full Flavor 100s Soft Pack Menthol Silver 100 Box Full Flavor 120s Box Menthol Silver King Box Full Flavor 72s Slide Box Non-filter King Box Full Flavor King Size Box Red 100 Box Full Flavor King Size Soft Pack Red King Box Medium 100s Box Silver 100 Box Medium King Size Box Silver King Box Menthol 100s Box Decade Menthol 100s Soft Pack Gold 100 Box Menthol 120s Box Gold King Box Menthol 72s Slide Box Menthol 100 Box Menthol King Size Box Menthol King Box Menthol King Size Soft Pack Menthol Silver 100 Box Nonfilter King Size Box Menthol Silver King Box Silver 100s Box Red 100 Box Silver 100s Soft Pack Red King Box Silver King Size Box Silver 100 Box Silver King Size Soft Pack Silver King Box Smooth 120s Box Smooth Menthol 100s Box Smooth Menthol 100s Soft Pack Grand River Enterprises Six Nations, Ltd. (NPM) Smooth Menthol 120s Box Couture Smooth Menthol King Size Box Smooth Menthol King Size Soft Pack Slims 100s Amethyst Box Ultra 120s Box Slims 100s Aquamarine Box Slims 100s Diamond Box -

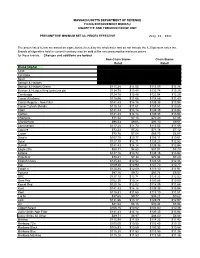

Cigarette Minimum Retail Price List

MASSACHUSETTS DEPARTMENT OF REVENUE FILING ENFORCEMENT BUREAU CIGARETTE AND TOBACCO EXCISE UNIT PRESUMPTIVE MINIMUM RETAIL PRICES EFFECTIVE July 26, 2021 The prices listed below are based on cigarettes delivered by the wholesaler and do not include the 6.25 percent sales tax. Brands of cigarettes held in current inventory may be sold at the new presumptive minimum prices for those brands. Changes and additions are bolded. Non-Chain Stores Chain Stores Retail Retail Brand (Alpha) Carton Pack Carton Pack 1839 $86.64 $8.66 $85.38 $8.54 1st Class $71.49 $7.15 $70.44 $7.04 Basic $122.21 $12.22 $120.41 $12.04 Benson & Hedges $136.55 $13.66 $134.54 $13.45 Benson & Hedges Green $115.28 $11.53 $113.59 $11.36 Benson & Hedges King (princess pk) $134.75 $13.48 $132.78 $13.28 Cambridge $124.78 $12.48 $122.94 $12.29 Camel All others $116.56 $11.66 $114.85 $11.49 Camel Regular - Non Filter $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Camel Turkish Blends $110.14 $11.01 $108.51 $10.85 Capri $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Carlton $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Checkers $71.54 $7.15 $70.49 $7.05 Chesterfield $96.53 $9.65 $95.10 $9.51 Commander $117.28 $11.73 $115.55 $11.56 Couture $72.23 $7.22 $71.16 $7.12 Crown $70.76 $7.08 $69.73 $6.97 Dave's $107.70 $10.77 $106.11 $10.61 Doral $127.10 $12.71 $125.23 $12.52 Dunhill $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Eagle 20's $88.31 $8.83 $87.01 $8.70 Eclipse $137.16 $13.72 $135.15 $13.52 Edgefield $73.41 $7.34 $72.34 $7.23 English Ovals $125.44 $12.54 $123.59 $12.36 Eve $109.30 $10.93 $107.70 $10.77 Export A $120.88 $12.09 $119.10 $11.91 -

Directory of Cigarettes Approved for Sale and Importation June 19, 2015

Directory of Cigarettes Approved for Sale and Importation June 19, 2015 The following cigarette manufacturers and their associated brands have been determined to be in compliance with Alaska Statutes 45.53.020 (see MSA Compliant Tobacco Manufacturers) and 18.74.010 (see Directory of Fire Safe Certified Brand Styles). Please be advised that cigarettes (to include roll-your-own) manufactured by companies not listed below may not be sold in Alaska. Cigarettes found in Alaska that are not on this list are contraband and subject to seizure and destruction. Violations of AS 45.53.020 may also be punished by revocation of a license issued under AS 43.50.010, 43.50.035, or 43.50.320 and imposition of civil and criminal penalties. Manufacturer type provides that the company is both a participating manufacturer (PM) and signatory to the Tobacco Master Settlement Agreement and all amendments to that agreement or a non-participating manufacturer (NPM) in full compliance with Alaska Statute 45.43. Lorillard Tobacco Company (Lorillard) merged with R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company (RJR) as of June 12, 2015. As a result of the merger, the ownership of certain of Lorillard’s and RJR’s brands has changed. Kent, Newport, Old Gold and True, formerly Lorillard brands, are now held by RJR; Maverick was transferred from Lorillard to ITG Brands, LLC (ITG); and Kool, Winston and Salem were transferred from RJR to ITG. Although the transfers were effective as of June 12, 2015, the companies are selling off their product that was already in the distribution chain as of June 12, 2015. -

Manufacturer Brand Style Length (Mm's) Circ

Iowa Approved Fire Standard Compliant Cigarettes -04/01/2021 (SORTED BY BRAND STYLE) Date Length Circ Certified/ Manufacturer Brand Style (mm's) (mm's) Flavor Filter Package Test Date Recertified Premier Manufacturing, Inc. 1839 Blue 100 Box 97.90 24.60 Regular Filter Box 03/30/18 01/11/21 Premier Manufacturing, Inc. 1839 Blue King Box 82.40 24.60 Regular Filter Box 04/03/18 01/11/21 Premier Manufacturing, Inc. 1839 Menthol Blue 100 Box 97.90 24.70 Menthol Filter Box 03/30/18 01/11/21 Premier Manufacturing, Inc. 1839 Menthol Blue King Box 82.90 24.60 Menthol Filter Box 04/04/18 01/11/21 Premier Manufacturing, Inc. 1839 Menthol Green 100 Box 97.30 24.60 Menthol Filter Box 04/02/18 01/11/21 Premier Manufacturing, Inc. 1839 Menthol Green King Box 83.00 24.50 Menthol Filter Box 04/04/18 01/11/21 Premier Manufacturing, Inc. 1839 Red 100 Box 97.80 24.60 Regular Filter Box 03/30/18 01/11/21 Premier Manufacturing, Inc. 1839 Red King Box 82.80 24.70 Regular Filter Box 04/03/18 01/11/21 Premier Manufacturing, Inc. 1839 Silver 100 Box 97.40 24.70 Regular Filter Box 04/03/18 01/11/21 Premier Manufacturing, Inc. 1839 Silver King Box 82.80 24.70 Regular Filter Box 04/04/18 01/11/21 Premier Manufacturing, Inc. 1st Class Blue 100's Box 97.10 24.60 Regular Filter Box 04/05/18 01/11/21 Premier Manufacturing, Inc. 1st Class Blue Kings Box 82.80 24.70 Regular Filter Box 04/05/18 01/11/21 Premier Manufacturing, Inc. -

Exemption from Substantial Equivalence Letter from FDA CTP

( ..-~~ 11,~U. S . FOOD& DRUG U.S. Food & Drug Administration 10903 New Hampshire Avenue \,:::if- ADMINISTRATION Silver Spring, MD 20993 www.fda.gov April 16, 2020 EXEMPT ITG Brands, LLC Attention: Carole Folmar, Senior Director, Product Integrity and Compliance 714 Green Valley Road Greensboro, NC 27408-7018 FDA Submission Tracking Numbers (STNs): Multiple STNs, see Appendix A Dear Ms. Folmar: We completed review of your EX REQs1 and determined that the new tobacco products listed in Appendix A are exempt from the requirements of Substantial Equivalence.2 Our finding does not mean we “approved” the new products specified in Appendix A; therefore, you may not promote or in any way represent the new tobacco products specified in Appendix A, or the labeling, as being “approved” by FDA (see Section 301(tt) of the FD&C Act). To market the new tobacco products that are the subject of these EX REQs, the following must be met: 1. Submit a report under section 905(j)(1) (Abbreviated Report) that includes the information required in sections 905(j)(1)(A)(ii) and 905(j)(1)(B); and 2. Ninety days have passed since FDA receipt of your Abbreviated Report. See Appendix B for FDA’s recommended format for submitting of an Abbreviated Report. In accordance with 40 CFR 1506.6, we will make your Environmental Assessment (EA) publicly available. All regulated tobacco products, including the tobacco products specified in Appendix A, are subject to the requirements of the FD&C Act and its implementing regulations. It is your responsibility to ensure the tobacco products specified in Appendix A comply with all applicable statutory and regulatory requirements. -

Higher Cigarette Prices Influence Cigarette Purchase Patterns a Hyland, J E Bauer, Q Li, S M Abrams, C Higbee, L Peppone, K M Cummings

86 RESEARCH PAPER Higher cigarette prices influence cigarette purchase patterns A Hyland, J E Bauer, Q Li, S M Abrams, C Higbee, L Peppone, K M Cummings ............................................................................................................................... Tobacco Control 2005;14:86–92. doi: 10.1136/tc.2004.008730 Objective: To examine cigarette purchasing patterns of current smokers and to determine the effects of cigarette price on use of cheaper sources, discount/generic cigarettes, and coupons. Background: Higher cigarette prices result in decreased cigarette consumption, but price sensitive smokers See end of article for may seek lower priced or tax-free cigarette sources, especially if they are readily available. This price authors’ affiliations ....................... avoidance behaviour costs states excise tax money and dampens the health impact of higher cigarette prices. Correspondence to: Methods: Telephone survey data from 3602 US smokers who were originally in the COMMIT (community K Michael Cummings, PhD, MPH, Roswell Park intervention trial for smoking cessation) study were analysed to assess cigarette purchase patterns, use of Cancer Institute, discount/generic cigarettes, and use of coupons. Department of Health Results: 59% reported engaging in a high price avoidance strategy, including 34% who regularly Behavior, Elm and Carlton purchase from a low or untaxed venue, 28% who smoke a discount/generic cigarette brand, and 18% Streets, Buffalo, New York 14263, USA; who report using cigarette coupons more frequently that they did five years ago. The report of engaging in michael.cummings@ a price avoidance strategy was associated with living within 40 miles of a state or Indian reservation with roswellpark.org lower cigarette excise taxes, higher average cigarette consumption, white, non-Hispanic race/ethnicity, Received 5 May 2004 and female sex. -

Unclaimed Property Reporting Instructions

2019 UNCLAIMED PROPERTY REPORTING INSTRUCTIONS GLENN HEGAR Texas Comptroller of Public Accounts UNCLAIMED PROPERTY REPORTING INSTRUCTIONS i Unclaimed Property Reporting Instructions Table of Contents CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION TO HOLDER REPORTING CHAPTER 3: PROPERTY-SPECIFIC REPORTING What is Unclaimed Property? .................................... 1 Crime Victims Restitution ....................................... 11 Types of Unclaimed Property ..................................... 1 Electric Cooperatives .............................................. 12 What is a Holder? ...................................................... 2 Escrow Funds Reported by Title Companies ......... 13 What Are My Responsibilities as a Holder? .............. 2 Financial Institutions ................................................14 What You Need to File Your Report ......................... 2 Insurance-Related Property .......................................21 Reporting Format ....................................................... 2 Local Government ................................................... 24 How Does the Reporting Process Work? ................. 3 Mineral Proceeds ...................................................... 24 Mutual Fund Shares, Distributions and Checks ...... 25 CHAPTER 2: FILING YOUR REPORT Securities or Securities-Related Cash ........................27 Determining Dormancy ............................................. 5 Notifying Property Owners ....................................... 6 CHAPTER 4: REFERENCE TABLES Other Methods -

Directory of Fire Safe Certified Cigarette Brand Styles Updated 4/29/10

Directory of Fire Safe Certified Cigarette Brand Styles Updated 4/29/10 Beginning August 1, 2008, only the cigarette brands and styles listed below are allowed to be imported, stamped and/or sold in the State of Alaska. Per AS 18.74, these brands must be marked as fire safe on the packaging. The brand styles listed below have been certified as fire safe by the State Fire Marshall, bear the "FSC" marking. There is an exception to these requirements. The new fire safe law allows for the sale of cigarettes that are not fire safe and do not have the "FSC" marking as long as they were stamped and in the State of Alaska before August 1, 2008 and found on the "Directory of MSA Compliant Cigarette & RYO Brands." Filter/ Non- Brand Style Length Circ. Filter Pkg. Descr. Manufacturer 1839 Full Flavor 82.7 24.60 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Full Flavor 97 24.60 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Full Flavor 83 24.60 Non-Filter Soft Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Light 83 24.40 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Light 97 24.50 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Menthol 97 24.50 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Menthol 83 24.60 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Menthol Light 83 24.50 Filter Hard Pack U.S. -

Directory of Fire Safe Certified Cigarette Brand Styles Updated 6/18/10

Directory of Fire Safe Certified Cigarette Brand Styles Updated 6/18/10 Beginning August 1, 2008, only the cigarette brands and styles listed below are allowed to be imported, stamped and/or sold in the State of Alaska. Per AS 18.74, these brands must be marked as fire safe on the packaging. The brand styles listed below have been certified as fire safe by the State Fire Marshall, bear the "FSC" marking. There is an exception to these requirements. The new fire safe law allows for the sale of cigarettes that are not fire safe and do not have the "FSC" marking as long as they were stamped and in the State of Alaska before August 1, 2008 and found on the "Directory of MSA Compliant Cigarette & RYO Brands." Filter/ Non- Brand Style Length Circ. Filter Pkg. Descr. Manufacturer 1839 Blue 100 Box 97 24.50 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Blue King Box 83 24.40 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Full Flavor 82.7 24.60 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Full Flavor 97 24.60 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Full Flavor 83 24.60 Non-Filter Soft Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Light 83 24.40 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Light 97 24.50 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Menthol 97 24.50 Filter Hard Pack U.S.