Download File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lake Baikal Russian Federation

LAKE BAIKAL RUSSIAN FEDERATION Lake Baikal is in south central Siberia close to the Mongolian border. It is the largest, oldest by 20 million years, and deepest, at 1,638m, of the world's lakes. It is 3.15 million hectares in size and contains a fifth of the world's unfrozen surface freshwater. Its age and isolation and unusually fertile depths have given it the world's richest and most unusual lacustrine fauna which, like the Galapagos islands’, is of outstanding value to evolutionary science. The exceptional variety of endemic animals and plants make the lake one of the most biologically diverse on earth. Threats to the site: Present threats are the untreated wastes from the river Selenga, potential oil and gas exploration in the Selenga delta, widespread lake-edge pollution and over-hunting of the Baikal seals. However, the threat of an oil pipeline along the lake’s north shore was averted in 2006 by Presidential decree and the pulp and cellulose mill on the southern shore which polluted 200 sq. km of the lake, caused some of the worst air pollution in Russia and genetic mutations in some of the lake’s endemic species, was closed in 2009 as no longer profitable to run. COUNTRY Russian Federation NAME Lake Baikal NATURAL WORLD HERITAGE SERIAL SITE 1996: Inscribed on the World Heritage List under Natural Criteria vii, viii, ix and x. STATEMENT OF OUTSTANDING UNIVERSAL VALUE The UNESCO World Heritage Committee issued the following statement at the time of inscription. Justification for Inscription The Committee inscribed Lake Baikal the most outstanding example of a freshwater ecosystem on the basis of: Criteria (vii), (viii), (ix) and (x). -

Buryat Cumhuriyeti'nin Turizm Potansiyeli Ve Başlıca

SDÜ FEN-EDEBİYAT FAKÜLTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER DERGİSİ, AĞUSTOS 2021, SAYI: 53, SS. 136-179 SDU FACULTY OF ARTS AND SCIENCES JOURNAL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES, AUGUST 2021, No: 53, PP. 136-179 Makale Geliş | Received : 07.06.2021 Makale Kabul | Accepted : 31.08.2021 Emin ATASOY Bursa Uludağ Üniversitesi, Türkçe ve Sosyal Bilimler Eğitimi Bölümü [email protected] ORCID Numarası|ORCID Numbers: 0000-0002-6073-6461 Erol KAPLUHAN Burdur Mehmet Akif Ersoy Üniversitesi, Coğrafya Bölümü [email protected] ORCID Numarası|ORCID Numbers: 0000-0002-2500-1259 Yerbol PANGALİYEV [email protected] ORCID Numarası|ORCID Numbers: 0000-0002-2392-4180 Buryat Cumhuriyeti’nin Turizm Potansiyeli ve Başlıca Turizm Kaynakları Touristic Potential And Major Touristic Attractions Of Buryatia Republic Öz Rusya Federasyonu’nun Güney Sibirya Bölgesi’nde yer alan Buryat Cumhuriyeti, Saha Cumhuriyeti ve Komi Cumhuriyeti’nden sonra Rusya’nın en büyük yüzölçümüne sahip üçüncü özerk cumhuriyetidir. Siyasi yapılanma olarak Uzakdoğu Federal İdari Bölgesi, ekonomik yapılanma olarak ise Uzakdoğu İktisadi Bölge sınırları içinde yer alan Buryatya, Doğu Sibirya’nın güney kesimlerinde ve Moğolistan’ın kuzeyinde yer almaktadır. Araştırmada coğrafyanın temel araştırma metotları gözetilmiş, kaynak tarama yöntemi aracılığıyla ilgili kaynaklar ve yayınlar temin edilerek veri tabanı oluşturulmuştur. Elde edilen verilerin değerlendirilmesi için haritalar, şekiller ve tablolar oluşturulmuştur. Konunun net anlaşılması amacıyla Buryat Cumhuriyeti’nin lokasyon, Buryat Cumhuriyeti Kültürel Turizm Merkezleri, Buryat Cumhuriyeti’nin Doğal turizm alanları, Buryat Cumhuriyeti milli parkları ve doğa koruma alanları haritalarının yanı sıra ifadeleri güçlendirmek için konular arasındaki bağlantılar tablo ile vurgulanmıştır. Tüm bu coğrafi olumsuzluklara rağmen, Buryatya zengin doğal kaynaklarıyla, geniş Tayga ormanlarıyla, yüzlerce göl ve akarsu havzasıyla, yüzlerce sağlık, kültür ve inanç merkeziyle, çok sayıda kaplıca, müze ve doğa koruma alanıyla, Rusya’nın en zengin turizm kaynaklarına sahip cumhuriyetlerinden biridir. -

History and Ethnography of Mongolian-Speaking Peoples in Materials of O.M

History and ethnography of Mongolian-speaking peoples in materials of O.M. Kowalewski in library holdings of Vilnius University Oksana N. Polyanskaya Buryat State University Abstract. The article is devoted to a famous diary that was written by Orientalist Osip (Józef) Michailovich Kowalewski and is being stored in the script department of the library of Vilnius University. This article is one of the first attempts to introduce it to the scientific field. The document, entitledDiary of Pursuits in 1832, is an important source of the history and ethnography of Mongolian-speaking peoples and is an essential supplement to well-known materials about these peoples. Since its foundation, Vilnius University has trained renowned scientists and researchers who have made its name famous in various fields of scientific knowledge. One of the outstanding scientists who graduated from Vilnius University is Osip (Józef) Michailovich Kowalewski (1801–1878), a globally known Orientalist and the founder of the European school of Mongolian-specific studies. Kowalewski did not move from Vilnius voluntarily. Being a member of the clandestine patriotic Society of Philomaths, he was exiled to Kazan in 1824 without the right to return to his home country barring a special decree (Baziyants 1990, 126–7). He nevertheless got facilities for scientific work in Kazan, in spite of finding himself in a tight corner. Excellent training in the field of classical philosophy in Kazan and proficiency in some European languages helped him achieve progress in his pursuit of Oriental studies, which started with him learning the Tatar language and history of the Tatar Khanate. Subsequently, he had to change the scope of his scientific research anew and became the founder of Mongolian-specific sciences. -

Human-Nature Relationships in the Tungus Societies of Siberia and Northeast China Alexandra Lavrillier, Aurore Dumont, Donatas Brandišauskas

Human-nature relationships in the Tungus societies of Siberia and Northeast China Alexandra Lavrillier, Aurore Dumont, Donatas Brandišauskas To cite this version: Alexandra Lavrillier, Aurore Dumont, Donatas Brandišauskas. Human-nature relationships in the Tungus societies of Siberia and Northeast China. Études mongoles et sibériennes, centrasiatiques et tibétaines, Centre d’Etudes Mongoles & Sibériennes / École Pratique des Hautes Études, 2018, Human-environment relationships in Siberia and Northeast China. Knowledge, rituals, mobility and politics among the Tungus peoples, 49, pp.1-26. 10.4000/emscat.3088. halshs-02520251 HAL Id: halshs-02520251 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-02520251 Submitted on 26 Mar 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Études mongoles et sibériennes, centrasiatiques et tibétaines 49 | 2018 Human-environment relationships in Siberia and Northeast China. Knowledge, rituals, mobility and politics among the Tungus peoples, followed by Varia Human-nature relationships in the Tungus societies of Siberia -

Northern European Overture to War, 1939–1941 History of Warfare

Northern European Overture to War, 1939–1941 History of Warfare Editors Kelly DeVries Loyola University Maryland John France University of Wales, Swansea Michael S. Neiberg United States Army War College, Pennsylvania Frederick Schneid High Point University, North Carolina VOLUME 87 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/hw Northern European Overture to War, 1939–1941 From Memel to Barbarossa Edited by Michael H. Clemmesen Marcus S. Faulkner LEIDEN • BOSTON 2013 Cover illustration: David Low cartoon on the Nazi-Soviet alliance published in Picture Post, 21 Oct 1939. Courtesy of Solo Syndication and the British Cartoon Archive. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Northern European overture to war, 1939–1941 : from Memel to Barbarossa / edited by Michael H. Clemmesen, Marcus S. Faulkner. pages cm. -- (History of warfare, ISSN 1385–7827 ; volume 87) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-24908-0 (hardback : acid-free paper) -- ISBN 978-90-04-24909-7 (e-book) 1. World War, 1939–1945--Campaigns--Europe, Northern. 2. World War, 1939–1945--Campaigns--Scandinavia. 3. World War, 1939–1945--Naval operations. 4. Baltic Sea--History, Naval--20th century. 5. World War, 1939–1945--Diplomatic history. 6. Europe, Northern--Strategic aspects. 7. Scandinavia--Strategic aspects. 8. Baltic Sea Region--Strategic aspects. I. Clemmesen, Michael Hesselholt, 1944- II. Faulkner, Marcus. D756.3.N67 2013 940.54’21--dc23 2013002994 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, IPA, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see www.brill.com/brill-typeface. -

Highland Gold Mining Limited

HIGHLAND GOLD MINING LIMITED IMPORTANT NOTICE This document, comprising a draft admission document, is being distributed by W.H. Ireland Limited ("W.H. Ireland"), which is regulated by the Financial Services Authority, as nominated adviser to Highland Gold Mining Limited (the "Company") in connection with the proposed placing of Existing Ordinary Shares and New Ordinary Shares of the Company that are to be traded on the Alternative Investment Market of London Stock Exchange plc ("AIM”) and admission of the issued and to be issued Ordinary Shares of the Company to trading on AIM ("Admission”). The information in this document, which is in draft form and is incomplete, is subject to updating, completion, revision, further verification and amendment. In particular, this document refers to certain events as having occurred which have not yet occurred but are expected to occur prior to publication of the final admission document or any supplemental prospectus relating to the Company. Furthermore, no assurance is given by the Company or W.H. Ireland that any New Ordinary Shares in the Company will be issued, Existing Ordinary Shares sold or that Admission will take place. No representation is made by W.H. Ireland or the Company or any of their advisers, representatives, agents, officers, directors or employees as to, and no responsibility, warranty or liability is accepted for, the accuracy, reliability, reasonableness or completeness of the contents of this document. No responsibility is accepted by any of them for any errors, mis-statements in, or omissions from, this document, nor for any direct or consequential loss howsoever arising from any use of, or reliance on, this document or otherwise in connection with it. -

In the Lands of the Romanovs: an Annotated Bibliography of First-Hand English-Language Accounts of the Russian Empire

ANTHONY CROSS In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of The Russian Empire (1613-1917) OpenBook Publishers To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/268 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917) Anthony Cross http://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2014 Anthony Cross The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt it and to make commercial use of it providing that attribution is made to the author (but not in any way that suggests that he endorses you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Cross, Anthony, In the Land of the Romanovs: An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917), Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/ OBP.0042 Please see the list of illustrations for attribution relating to individual images. Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omissions or errors will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. As for the rights of the images from Wikimedia Commons, please refer to the Wikimedia website (for each image, the link to the relevant page can be found in the list of illustrations). -

Trans-Baykal (Rusya) Bölgesi'nin Coğrafyasi

International Journal of Geography and Geography Education (IGGE) To Cite This Article: Can, R. R. (2021). Geography of the Trans-Baykal (Russia) region. International Journal of Geography and Geography Education (IGGE), 43, 365-385. Submitted: October 07, 2020 Revised: November 01, 2020 Accepted: November 16, 2020 GEOGRAPHY OF THE TRANS-BAYKAL (RUSSIA) REGION Trans-Baykal (Rusya) Bölgesi’nin Coğrafyası Reyhan Rafet CAN1 Öz Zabaykalskiy Kray (Bölge) olarak isimlendirilen saha adını Rus kâşiflerin ilk kez 1640’ta karşılaştıkları Daur halkından alır. Rusçada Zabaykalye, Balkal Gölü’nün doğusu anlamına gelir. Trans-Baykal Bölgesi, Sibirya'nın en güneydoğusunda, doğu Trans-Baykal'ın neredeyse tüm bölgesini işgal eder. Bölge şiddetli iklim koşulları; birçok mineral ve hammadde kaynağı; ormanların ve tarım arazilerinin varlığı ile karakterize edilir. Rusya Federasyonu'nun Uzakdoğu Federal Bölgesi’nin bir parçası olan on bir kurucu kuruluşu arasında bölge, alan açısından altıncı, nüfus açısından dördüncü, bölgesel ürün üretimi açısından (GRP) altıncı sıradadır. Bölge topraklarından geçen Trans-Sibirya Demiryolu yalnızca Uzak Doğu ile Rusya'nın batı bölgeleri arasında bir ulaşım bağlantısı değil, aynı zamanda Avrasya geçişini sağlayan küresel altyapının da bir parçasıdır. Bölgenin üretim yapısında sanayi, tarım ve ulaşım yüksek bir paya sahiptir. Bu çalışmada Trans-Baykal Bölgesi’nin fiziki, beşeri ve ekonomik coğrafya özellikleri ele alınmıştır. Trans-Baykal Bölgesinin coğrafi özelliklerinin yanı sıra, ekonomik ve kültürel yapısını incelenmiştir. Bu kapsamda konu ile ilgili kurumsal raporlardan ve alan araştırmalarından yararlanılmıştır. Bu çalışma sonucunda 350 yıldan beri Rus gelenek, kültür ve yaşam tarzının devam ettiği, farklı etnik grupların toplumsal birliği sağladığı, yer altı kaynaklarının bölge ekonomisi için yüzyıllardır olduğu gibi günümüzde de önem arz ettiği, coğrafyasının halkın yaşam şeklini belirdiği sonucuna varılmıştır. -

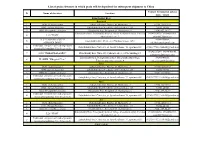

List of Grain Elevators in Which Grain Will Be Deposited for Subsequent Shipment to China

List of grain elevators in which grain will be deposited for subsequent shipment to China Contact Infromation (phone № Name of elevators Location num. / email) Zabaykalsky Krai Rapeseed 1 ООО «Zabaykalagro» Zabaykalsku krai, Borzya, ul. Matrosova, 2 8-914-120-29-18 2 OOO «Zolotoy Kolosok» Zabaykalsky Krai, Nerchinsk, ul. Octyabrskaya, 128 30242-44948 3 OOO «Priargunskye prostory» Zabaykalsky Krai, Priargunsk ul. Urozhaynaya, 6 (924) 457-30-27 Zabaykalsky Krai, Priargunsky district, village Starotsuruhaytuy, Pertizan 89145160238, 89644638969, 4 LLS "PION" Shestakovich str., 3 [email protected] LLC "ZABAYKALSKYI 89144350888, 5 Zabaykalskyi krai, Chita city, Chkalova street, 149/1 AGROHOLDING" [email protected] Individual entrepreneur head of peasant 6 Zabaykalskyi krai, Chita city, st. Juravleva/home 74, apartment 88 89243877133, [email protected] farming Kalashnikov Uriy Sergeevich 89242727249, 89144700140, 7 OOO "ZABAYKALAGRO" Zabaykalsky krai, Chita city, Chkalova street, 147A, building 15 [email protected] Zabaykalsky krai, Priargunsky district, Staroturukhaitui village, 89245040356, 8 IP GKFH "Mungalov V.A." Tehnicheskaia street, house 4 [email protected] Corn 1 ООО «Zabaykalagro» Zabaykalsku krai, Borzya, ul. Matrosova, 2 8-914-120-29-18 2 OOO «Zolotoy Kolosok» Zabaykalsky Krai, Nerchinsk, ul. Octyabrskaya, 128 30242-44948 3 OOO «Priargunskye prostory» Zabaykalsky Krai, Priargunsk ul. Urozhaynaya, 6 (924) 457-30-27 Individual entrepreneur head of peasant 4 Zabaykalskyi krai, Chita city, st. Juravleva/home 74, apartment 88 89243877133, [email protected] farming Kalashnikov Uriy Sergeevich Rice 1 ООО «Zabaykalagro» Zabaykalsku krai, Borzya, ul. Matrosova, 2 8-914-120-29-18 2 OOO «Zolotoy Kolosok» Zabaykalsky Krai, Nerchinsk, ul. Octyabrskaya, 128 30242-44948 3 OOO «Priargunskye prostory» Zabaykalsky Krai, Priargunsk ul. -

“Ełk - a History Driven by Trains” - Exhibition Scenario

“Ełk - a history driven by trains” - Exhibition Scenario Date: June - October 2019 Historical Museum in Ełk, ul. Wąski Tor 1 1. “Long Middle Ages” The settlement, out of which Ełk developed, was founded in 1425 near a guardhouse built around 1398 - later to become a castle. The inhabitants lived according to the rhythm of the changing seasons. People of the Middle Ages were dependent on nature. Existence was conditioned by favourable (or not) natural factors such as good harvest or famine, floods, fires, and severe winters. People lived in constant fear of potential epidemics or diseases resulting from malnutrition or poor hygiene. No machines existed to improve tillage. The economy depended on the strength of human and animal muscles. Faith in miracles and supernatural powers was widespread. The end of the Middle Ages is traditionally marked in the second half of the 15th century. The events that would give rise to a new era included the invention of printing in 1452 and the fall of Constantinople in 1453. However, did these factors influence the life of the inhabitants of Ełk and Prussia (in which the town was located at the time)? People kept using the same tools and animals in farming. The population was constantly at risk of hunger and diseases, about which almost nothing was known and for which practically no medicines existed. Historic turning points, such as the invention of printing, only impacted the lives of the few elite of society in those times. The average person lived the same way in the year 1400 as in 1700. -

Universitas Gedanensis T. 51

UNIVERSITAS GE DA NEN SIS t. 51 UNIVERSITAS GEDANENSIS PÓŁROCZNIK R. 28 2016 t. 51 Pomorskie Towarzystwo Filozoficzno-Teologiczne Universitas Gedanensis, t. 51 Redaktor naczelny Ks. Zdzisław Kropidłowski Sekretarz redakcji Joanna Gomoliszek, Jan Grzanka Kolegium redakcyjne: Janusz Jasiński (Olsztyn), Feliks Krauze (Gdańsk), Ks. Janusz Mariański (Lublin), Anna Peck (Warszawa), Aurelia Polańska (Gdańsk), Andrzej Wałkówski (Łódź), Władysław Zajewski (Gdańsk) Redaktor językowy Teresa Ossowska Korektor Katarzyna Kornicka Projekt okładki Sylwia Mikołajewska Wersja elektroniczna od tomu 46 „Universitas Gedanensis” jest wersją pierwotną czasopisma http://universitasgedanensis.com.pl https://universitasgedanensis.wordpress.com Wydawca Pomorskie Towarzystwo Filozoficzno-Teologiczne Ul. Lendziona 8/1a 80-264 Gdańsk Telefon redakcji: +48 608 358 244 Druk Poligrafia Redemptorystów ul. Wysoka 1 33-170 Tuchów Nakład 120 egzemplarzy ISSN 1230-0152 Spis treści Zdzisław Kropidłowski, Piekarze gdańscy klientami introligatorów .............................7 Elżbieta Pokorzyńska, Introligatorzy gdańscy XIX-wieku w świetle dokumentacji cechowej ...........................................................................................................31 Piotr Rumanowski, „Ukrzyżowanie” w barokowym malarstwie sakralnym dawnego archidiakonatu pomorskiego - repliki warsztatowe, wybrane przykłady ................49 Jerzy Konieczny, Nienapisana monografia. Fredriana Adama Grzymały-Siedleckiego ...73 Mirosław Kuczkowski, Pozaduszpasterska działalność Sługi Bożego, -

Out of the Shadows: Socially Engaged Buddhist Women

University of San Diego Digital USD Theology and Religious Studies: Faculty Scholarship Department of Theology and Religious Studies 2019 Out of the Shadows: Socially Engaged Buddhist Women Karma Lekshe Tsomo PhD University of San Diego, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.sandiego.edu/thrs-faculty Part of the Buddhist Studies Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Digital USD Citation Tsomo, Karma Lekshe PhD, "Out of the Shadows: Socially Engaged Buddhist Women" (2019). Theology and Religious Studies: Faculty Scholarship. 25. https://digital.sandiego.edu/thrs-faculty/25 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Theology and Religious Studies at Digital USD. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theology and Religious Studies: Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Digital USD. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Section Titles Placed Here | I Out of the Shadows Socially Engaged Buddhist Women Edited by Karma Lekshe Tsomo SAKYADHITA | HONOLULU First Edition: Sri Satguru Publications 2006 Second Edition: Sakyadhita 2019 Copyright © 2019 Karma Lekshe Tsomo All rights reserved No part of this book may not be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, or by any information storage or retreival system, without the prior written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations. Cover design Copyright © 2006 Allen Wynar Sakyadhita Conference Poster