Demin on Selenginsk--Three New Publications

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lake Baikal Russian Federation

LAKE BAIKAL RUSSIAN FEDERATION Lake Baikal is in south central Siberia close to the Mongolian border. It is the largest, oldest by 20 million years, and deepest, at 1,638m, of the world's lakes. It is 3.15 million hectares in size and contains a fifth of the world's unfrozen surface freshwater. Its age and isolation and unusually fertile depths have given it the world's richest and most unusual lacustrine fauna which, like the Galapagos islands’, is of outstanding value to evolutionary science. The exceptional variety of endemic animals and plants make the lake one of the most biologically diverse on earth. Threats to the site: Present threats are the untreated wastes from the river Selenga, potential oil and gas exploration in the Selenga delta, widespread lake-edge pollution and over-hunting of the Baikal seals. However, the threat of an oil pipeline along the lake’s north shore was averted in 2006 by Presidential decree and the pulp and cellulose mill on the southern shore which polluted 200 sq. km of the lake, caused some of the worst air pollution in Russia and genetic mutations in some of the lake’s endemic species, was closed in 2009 as no longer profitable to run. COUNTRY Russian Federation NAME Lake Baikal NATURAL WORLD HERITAGE SERIAL SITE 1996: Inscribed on the World Heritage List under Natural Criteria vii, viii, ix and x. STATEMENT OF OUTSTANDING UNIVERSAL VALUE The UNESCO World Heritage Committee issued the following statement at the time of inscription. Justification for Inscription The Committee inscribed Lake Baikal the most outstanding example of a freshwater ecosystem on the basis of: Criteria (vii), (viii), (ix) and (x). -

In the Lands of the Romanovs: an Annotated Bibliography of First-Hand English-Language Accounts of the Russian Empire

ANTHONY CROSS In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of The Russian Empire (1613-1917) OpenBook Publishers To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/268 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917) Anthony Cross http://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2014 Anthony Cross The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt it and to make commercial use of it providing that attribution is made to the author (but not in any way that suggests that he endorses you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Cross, Anthony, In the Land of the Romanovs: An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917), Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/ OBP.0042 Please see the list of illustrations for attribution relating to individual images. Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omissions or errors will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. As for the rights of the images from Wikimedia Commons, please refer to the Wikimedia website (for each image, the link to the relevant page can be found in the list of illustrations). -

Subject of the Russian Federation)

How to use the Atlas The Atlas has two map sections The Main Section shows the location of Russia’s intact forest landscapes. The Thematic Section shows their tree species composition in two different ways. The legend is placed at the beginning of each set of maps. If you are looking for an area near a town or village Go to the Index on page 153 and find the alphabetical list of settlements by English name. The Cyrillic name is also given along with the map page number and coordinates (latitude and longitude) where it can be found. Capitals of regions and districts (raiony) are listed along with many other settlements, but only in the vicinity of intact forest landscapes. The reader should not expect to see a city like Moscow listed. Villages that are insufficiently known or very small are not listed and appear on the map only as nameless dots. If you are looking for an administrative region Go to the Index on page 185 and find the list of administrative regions. The numbers refer to the map on the inside back cover. Having found the region on this map, the reader will know which index map to use to search further. If you are looking for the big picture Go to the overview map on page 35. This map shows all of Russia’s Intact Forest Landscapes, along with the borders and Roman numerals of the five index maps. If you are looking for a certain part of Russia Find the appropriate index map. These show the borders of the detailed maps for different parts of the country. -

Dilemmas of Diversity After the Cold War: Analyses of “Cultural Difference” by U.S

Kennan Institute DILEMMAS OF DIVERSITY AFTER THE COLD WAR: Analyses of “Cultural Difference” by U.S. and Russia-Based Scholars Edited by Michele Rivkin-Fish and Elena Trubina DILEMMAS OF DIVERSITY AFTER THE COLD WAR: Analyses of “Cultural Difference” by U.S. and Russia-Based Scholars By Michele Rivkin-Fish and Elena Trubina WOODROW WILSON INTERNATIONAL CENTER FOR ScHOLARS The Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, established by Congress in 1968 and headquartered in Washington, D.C., is a living national memorial to President Wilson. The Center’s mission is to com- memorate the ideals and concerns of Woodrow Wilson by providing a link between the worlds of ideas and policy, while fostering research, study, discussion, and collaboration among a broad spectrum of individuals con- cerned with policy and scholarship in national and international affairs. Supported by public and private funds, the Center is a nonpartisan in- stitution engaged in the study of national and world affairs. It establish- es and maintains a neutral forum for free, open, and informed dialogue. Conclusions or opinions expressed in Center publications and programs are those of the authors and speakers and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Center staff, fellows, trustees, advisory groups, or any individuals or organizations that provide financial support to the Center. The Center is the publisher of The Wilson Quarterly a nd home of Wood row Wilson Center Press, dialogue radio and television, and the monthly news- letter “Centerpoint.” For more information about the Center’s activities and publications, please visit us on the web at www.wilsoncenter.org. -

People and Place Curriculum Resources on Human-Environmental Interactions

People and Place Curriculum Resources on Human-Environmental Interactions Hemispheres is a joint project of: Teresa Lozano Long Institute of Latin American Studies Center for Middle Eastern Studies Center for Russian, East European & Eurasian Studies South Asia Institute in the College of Liberal Arts at The University of Texas at Austin Hemispheres People and Place Curriculum Resources on Human-Environmental Interactions Primary Authors: Natalie Arsenault, Outreach Coordinator Teresa Lozano Long Institute of Latin American Studies Christopher Rose, Outreach Coordinator Center for Middle Eastern Studies Allegra Azulay, Outreach Coordinator Center for Russian, East European & Eurasian Studies Jordan Phillips, Outreach Coordinator South Asia Institute People and Place Curriculum Resources on Human-Environmental Interactions Final Version Original Compilation Date: June 2005 Final Publication Date: April 2007 Permission is granted to reproduce this unit for classroom use only. Please do not redistribute this unit without prior permission. For more information, please see: http://www.utexas.edu/cola/orgs/hemispheres/ Permission to include copyrighted materials in this unit is indicated in citations. LakeLake Baikal Baikal (Siberia) (Siberia) TEACHER NOTES GOALS This case study will help your students learn about the causes and effects of water pollution in the world by looking at Lake Baikal, located in Siberia. As a major source of the world’s fresh lake water, Lake Baikal is exceptional in its size and ability to withstand pollutants. However, because of residents’ assumptions that the lake will endure anything, it is also highly threatened (see The Aral Sea case study for an example of what can happen when water is not managed well). -

Waterbirds of Lake Baikal, Eastern Siberia, Russia

FORKTAIL 25 (2009): 13–70 Waterbirds of Lake Baikal, eastern Siberia, Russia JIŘÍ MLÍKOVSKÝ Lake Baikal lies in eastern Siberia, Russia. Due to its huge size, its waterbird fauna is still insufficiently known in spite of a long history of relevant research and the efforts of local and visiting ornithologists and birdwatchers. Overall, 137 waterbird species have been recorded at Lake Baikal since 1800, with records of five further species considered not acceptable, and one species recorded only prior to 1800. Only 50 species currently breed at Lake Baikal, while another 11 species bred there in the past or were recorded as occasional breeders. Only three species of conservation importance (all Near Threatened) currently breed or regularly migrate at Lake Baikal: Asian Dowitcher Limnodromus semipalmatus, Black-tailed Godwit Limosa limosa and Eurasian Curlew Numenius arquata. INTRODUCTION In the course of past centuries water levels in LB fluctuated considerably (Galaziy 1967, 1972), but the Lake Baikal (hereafter ‘LB’) is the largest lake in Siberia effects on the local avifauna have not been documented. and one of the largest in the world. Avifaunal lists of the Since the 1950s, the water level in LB has been regulated broader LB area have been published by Gagina (1958c, by the Irkutsk Dam. The resulting seasonal fluctuations 1960b,c, 1961, 1962b, 1965, 1968, 1988), Dorzhiyev of water levels significantly influence the distribution and (1990), Bold et al. (1991), Dorzhiyev and Yelayev (1999) breeding success of waterbirds (Skryabin 1965, 1967a, and Popov (2004b), but the waterbird fauna has not 1995b, Skryabin and Tolchin 1975, Lipin et al. -

Religion and Identity in Buryatia: Competition Between Orthodoxy and Buddhism in Imperial Russia

Volume3 Issue 2 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF HUMANITIES AND September 2016 CULTURAL STUDIES ISSN 2356-5926 Religion and Identity in Buryatia: Competition between Orthodoxy and Buddhism in Imperial Russia Darima Amogolonova Leading researcher, Dr. of Sciences in History, Institute for Mongolian, Buddhist and Tibetan Studies, Siberian Branch, Russian Academy of Sciences, Ulan-Ude, Russia The research was supported by the Russian Science Foundation in the framework of the Research Project “Buddhism in the Socio-Political and Cultural Processes in Russia, Inner and East Asia: Transformations and Prospects», № 14-18-00444. Abstract The paper discusses political importance of religious identity in the context of competition between Orthodoxy and Buddhism in the Buryat spiritual space. Christianization of Buryats, who are one of the biggest Siberian indigenous ethnic groups, as well as other non-Russians in the remote regions of Russia, seemed a necessary tool for strengthening the borders of the Empire under threat from Qing China. While Christianization of Pre-Baikal (Western) Buryats-shamanists was quite successful at least formally, the Trans-Baikal Buryats remained largely steadfast Buddhists. Considering this fact, the secular authorities built relationships with the Buddhist clergy in the framework of the existed legal regulations. However, the relation of the Orthodoxy towards Buddhism was irreconcilable overall the imperial history. The situation worsened at the end of the XIX century, when in connection with the Buryat ethnonational movements Buddhism began to spread among Western Buryats causing serious trouble to the Irkutsk Orthodox eparchy. Meanwhile, in addition to big adaptive ability, institutionalized Buddhism in Russia developed all-Buryat adoration and devotion to the Tsar through appropriate preaching among believers thus promoting and strengthening both its own positions and Russian identity of the Buryats. -

Plume Moths of Siberia and the Russian Far East P. Y

©Ges. zur Förderung d. Erforschung von Insektenwanderungen e.V. München, download unter www.zobodat.at Atalanta (May 1996) 27 (1/2): 345-409, Wurzburg, ISSN 0171-0079 Plume moths of Siberia and the Russian Far East (Lepidoptera, Pterophoridae) by P. Ya . U s t ju z h a n in received 4.XI.1994 Sum m ary: The study of rich material of Pterophoridae from Siberia and the Russian Far East revealed 96 species to inhabit these regions. 24 of them are reported for the first time from Asian Russia and 11 species and 2 genera (S ibiretta gen. nov. and Septuaginta gen. nov.) are described as new. Furthermore the genus Snellenia gen. nov. is described and isolated from the genus Stenoptilia, and previously unknown females are described for three species. Pe3K>Me: kteyHeHMe öoraToro MaTepnana no Pterophoridae Cn 6npn m fla/ibHero B octoio POCCMM BblflBM/10, MTO Ha 3T0M TeppMTOpHM BCTpeMaiOTCfl 96 BMflOB, 24 H3 KOTOpbIX npMBOflflTCfl Ann AskiaTCKOM P occmm BnepBbie. 11 bmaob h 2 poaa (S ibiretta m Septuaginta) onncbiBaioTCH Kax HOBbie, KpoMe Toro, M3 pofla Stenoptilia BbiaeneH poa Snellenia, a Ann Tpex bmaob onM- CblBaKDTCfl paHee HeM3BeCTHbie C3MKM. This paper summarises an extensive study of rich material of Pterophoridae from Siberia and the Russian Far East, which is referenced below in detail. As a result of this study 96 species were recorded in Asian Russia, 24 of which for the first time, and numerous novel data on species distribution were obtained. Eleven new species and two new genera were estab lished and a new genus S nellenia was isolated from the genus Stenoptilia Hubner . -

Download File

REVIEW Appointment in Dauria: HARRIMAN George Kennan, George Frost, and the Architectural Context Text and Photographs by William Craft Brumfield May 2012 THE HARRIMAN REVIEW Volume 18, Numbers 2-4 May 2012 William Craft Brumfield Appointment in Dauria: George Kennan, George Frost, and the Architectural Context 3 Appendix. Excerpts from George Kennan's Siberia and the Exile System 59 Notes 67 Cover photograph: Cathedral of the Dormition, Nerchinsk Dormition Monastery, southwest view. Taken by the author in the fall of 2000. THE HARRIMAN REVIEW, successor to The Harriman Institute Forum, is published quarterly by the Harriman Institute, Columbia University. Copyright © 2012 by the Trustees of Columbia University in the City of New York. All rights reserved. Reproduction of any kind without written permission is strictly forbidden. Annual subscription rates: U.S. and Canada: $35.00 (1 year), $60.00 (2 years); elsewhere: $45.00 (1 year), $85.00 (2 years). Back issues: $10.00 (includes postage). Check or money order should be made payable to Columbia University. U.S. funds only. Send all orders, changes of address, and subscription inquiries to: The Harriman Review, 1216 International Affairs Building, Columbia University, 420 West 118th Street, New York, New York 10027. The Harriman Review is indexed by PAIS and ABSEES. Harriman Institute http://www.harriman.columbia.edu/ 420 West 118th Street, MC 3345, Columbia University, New York, New York 10027 Appointment in Dauria: George Kennan, George Frost, and the Architectural Context William C. Brumfield (1) GATE CHURCH OF ARCHANGEL MICHAEL, TRINITY-SELENGINSK MONASTERY, SOUTH VIEW. ALL PHOTOGRAPHS TAKEN BY THE AUTHOR IN 1999 AND 2000. -

Lake Baikal Experience and Lessons Learned Brief

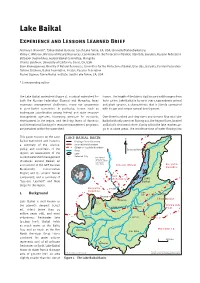

Lake Baikal Experience and Lessons Learned Brief Anthony J. Brunello*, Tahoe-Baikal Institute, South Lake Tahoe, CA, USA, [email protected] Valery C. Molotov, Ministry of Natural Resources, Committee for the Protection of Baikal, Ulan Ude, Buryatia, Russian Federation Batbayar Dugherkhuu, Federal Baikal Committee, Mongolia Charles Goldman, University of California, Davis, CA, USA Erjen Khamaganova, Ministry of Natural Resources, Committee for the Protection of Baikal, Ulan Ude, Buryatia, Russian Federation Tatiana Strijhova, Baikal Foundation, Irkutsk, Russian Federation Rachel Sigman, Tahoe-Baikal Institute, South Lake Tahoe, CA, USA * Corresponding author The Lake Baikal watershed (Figure 1), a critical watershed for France. The length of the lake is 636 km and width ranges from both the Russian Federation (Russia) and Mongolia, faces 80 to 27 km. Lake Baikal is home to over 1,500 endemic animal enormous management challenges, many not uncommon and plant species, a characteristic that is closely connected in post-Soviet economies. In particular, issues such as with its age and unique natural development. inadequate coordination among federal and state resource management agencies, increasing pressure for economic Over three hundred and sixty rivers and streams fl ow into Lake development in the region, and declining levels of domestic Baikal with only one river fl owing out, the Angara River, located and international funding for resource management programs, on Baikal’s northwest shore. Clarity within the lake reaches 40- are -

Geo-Ecological Aspects of the Territorial Organization of Tourist and Recreational Activities

MATEC Web of Conferences 193, 05018 (2018) https://doi.org/10.1051/matecconf/201819305018 ESCI 2018 Geo-ecological aspects of the territorial organization of tourist and recreational activities Arnold Tulokhonov1, Lyudmila Maksanova1, Darima Budaeva1 and Inessa Karnaukh2,* 1Baikal Institute of Nature Management, Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences 8 Sakhyanovoi St., 670047, Ulan-Ude, Russia 2Plekhanov Russian University of Economics, Ctremyannyj per., 36, 117997, Moscow, Russia Abstract. Various types of tourist and recreational activities have been developed, implemented, and pilot-tested in the regions for a long while. These activities translate into particular actions aimed at the improvement of the regional system of the government regulation and support of recreational activities. The need to preserve the unique ecosystem of Lake Baikal and to focus the socioeconomic development of the Baikal natural area on its environmental aspects have boosted the academic and practical interest in the geo-ecological aspects of the territorial organization of the tourist and recreational activities there. In the course of the research, the co- authors have identified and listed the local recreational areas and made a predictive assessment of the maximal acceptable recreational load value. The co-authors have assessed the potential adverse impact that may be produced on the environment components by the recreational facilities. On the basis of the research, the co-authors have issued their recommendations concerning the recreational -

Spatial-Temporal Variability of Small Gas Impurities Over Lake Baikal During the Forest Fires in the Summer of 2019

atmosphere Article Spatial-Temporal Variability of Small Gas Impurities over Lake Baikal during the Forest Fires in the Summer of 2019 Galina Zhamsueva *, Alexander Zayakhanov, Vadim Tcydypov, Ayuna Dementeva and Tumen Balzhanov Institute of Physical Materials Science Siberian Branch, Russian Academy of Sciences, 670047 Ulan-Ude, Russia; [email protected] (A.Z.); [email protected] (V.T.); [email protected] (A.D.); [email protected] (T.B.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +7-30-1243-4664 Abstract: Lake Baikal—a unique ecosystem on a global scale—is undoubtedly of great interest for a comprehensive study of its ecosystem. In recent years, one of the most significant sources of atmospheric pollution in the Baikal region was the emission of smoke aerosol and trace gases from forest fires, the number of which is increasing in the region. The transport and accumulation of aerosol and small gas impurities over water area of Lake Baikal is observed every summer due to forest fires occurring in the boreal forests of Siberia. The atmosphere above the lake covers a huge area (31,500 km2) and is still a little-studied object. This article presents the results of experimental studies of ground-level ozone, sulfur dioxide, and nitrogen oxides in the atmosphere over Lake Baikal, carried out on a research vessel during the boreal forest fires in Siberia in the summer of 2019. Keywords: Lake Baikal; ground-level ozone; nitrogen oxides; sulfur dioxide; forest fires; research vessel “Academik V.A. Koptyug” Citation: Zhamsueva, G.; 1. Introduction Zayakhanov, A.; Tcydypov, V.; All fresh-water ecosystems are exposed to the stress inherent in a complicated sys- Dementeva, A.; Balzhanov, T.