Beech Creek and Clay County, 1850–1910

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Support Still Strong for James White Parkway Extension

December 17, 2012 www.knoxfocus.com PAGE A1 INSIDE B Business C Sports D Health & Home MONDAY December 17, 2012 FREE- Take One! FOCUS Weekly Poll* Focus launches 24/7 Do you support By Focus Staff or oppose the overwhelmed with requests extension of Could you use some for additional, quality local James White ‘good’ news? We thought news. We answered that so. request with 24/7, your Parkway from With that in mind, source for breaking local Moody Ave, where The Focus is pleased to news. it currently ends, announce the launch of 24/7 is a blog compo- The Focus is committed edition- which hits news- you through www.knoxfo- to John Sevier 24/7, our latest contribu- nent of KnoxFocus.com. to variety, so in addition stands every Monday. cus.com and KnoxFocus Highway? tion to the Knoxville media Through 24/7, Focus read- to daily news briefs, mem- We would like to person- 24/7. market. With the addition ers will now be able to enjoy bers of our diverse staff ally thank you for allow- To visit 24/7 click on the of Farragut to our cover- community focused, local will offer personal perspec- ing us to be your preferred logo (pictured above) on the SUPPORT 69.29% age area, on top of the news 24 hours per day, 7 tive, political commentary, source for local news over top right of our homepage. OPPPOSE 30.71% entirety of Knox County days per week instead of and investigative reporting the last 10 years and look and Seymour, we were having to wait for a week. -

NEWSLETTER October 2013

October 2013 NEWSLETTER Vol. 35, No. 3 COMMITTED TO COLLECTING, PRESERVING, AND SHARING THE UNIQUE HERITAGE OF OUR COUNTY This issue of the Historical Society Newsletter is featuring some wonderful articles written by our members. Enjoy! Two Petitions The County Seat Should be Further West, 1777 When legislation was passed in late 1776 to divide Fincastle into Montgomery, Washington, and Kentucky counties, Black’s Fort was designated as the county seat for Washington. The legislation went into effect on January 1, 1777. At that time, the southern border of Virginia had not been determined in the area, and many people believed that it was at the South Holston River. The people who were living in what is now East Tennessee thought they lived in Washington County. For them, Black’s Fort was too distant. They petitioned the General Assembly for a more convenient center of government. They stated that they “….were greatly injured in the Division of Fincastle in the year 1776 by the manner in which the line was directed to be run." At that time, Montgomery County bordered Washington County, and the petitioners showed their displeasure that the border of Washington County was only thirty miles from the Montgomery line and twelve miles from North Carolina. The pointed out that what they believed to be the lower border of Washington County was seventy miles from Black's Fort. They wanted the seat of govern- ment to be near the center of the county. Approximately seventy-five men signed the petition. Had their petition been acted on, the county seat could have been in present-day Tennessee. -

A Brief History of Knoxville

HOlston Treaty statue on Volunteer landing a brief history of knoxville Before the United States, the Tennessee European discovery of the Mississippi River. country was the mysterious wild place Historians surmise he came right down the beyond the mountains, associated with Native north shore of the Tennessee River, directly American tribes. Prehistoric Indians of the through the future plot of Knoxville. DeSoto Woodland culture settled in the immediate began 250 years of colonial-era claims by Knoxville area as early as 800 A.D. Much Spain, France, and England, none of whom of their story is unknown. They left two effectively controlled the area. British mysterious mounds within what’s now explorers made their way into the region in Knoxville’s city limits. the early 1700s, when the future Tennessee Some centuries later, Cherokee cultures was counted as part of the Atlantic seaboard developed in the region, concentrated some colony of North Carolina. Fort Loudoun, built 40 miles downriver along what became in 1756 about 50 miles southwest of the future known as the Little Tennessee. The Cherokee site of Knoxville, was an ill-fated attempt probably knew the future Knoxville area to establish a British fort during the French mainly as a hunting ground. and Indian War. Hardly three years after Spanish explorer Hernando DeSoto its completion, Cherokee besieged the fort, ventured into the area in 1541 during his capturing or killing most of its inhabitants. famous expedition that culminated in the 1780 JOHN SEVIER LEADS SETTLERS TO VICTORY IN BATTLE OF KING’S MOUNTAIN 1783 1775 revolutionary war 1786 james white builds his fort and mill Hernando DeSoto, seen here on horseback discovering the Mississippi River, explored the East Tennessee region in 1541 3 Treaty of Holston, 1791 pioneers, created a crude settlement here. -

The Intersection of Kinship, Diplomacy, and Trade on the Trans- Montane Backcountry, 1600-1800

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar History Faculty Research History 10-1-2008 Appalachia’s Borderland Brokers: The nI tersection of Kinship, Diplomacy, and Trade on the Trans- montane Backcountry, 1600-1800 Kevin T. Barksdale Marshall University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/history_faculty Part of the Native American Studies Commons, Political History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Barksdale, Kevin T. "Appalachia’s Borderland Brokers: The nI t." Ohio Valley History Conference. Clarksville, TN. Oct. 2008. Address. This Presentation is brought to you for free and open access by the History at Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Faculty Research by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Appalachia’s Borderland Brokers: The Intersection of Kinship, Diplomacy, and Trade on the Trans- montane Backcountry, 1600-1800 This paper and accompanying historical argument builds upon the presentation I made at last year’s Ohio Valley History Conference held at Western Kentucky University. In that presentation, I argued that preindustrial Appalachia was a complex and dynamic borderland region in which disparate Amerindian groups and Euroamericans engaged in a wide-range of cultural, political, economic, and familial interactions. I challenged the Turnerian frontier model that characterized the North American backcountry -

Past Governors and Constitutional Officers of Tennessee

Past Governors and Constitutional Officers of Tennessee Past Governors William Blount 1790–1795, Democratic-Republican (territorial governor) Born in North Carolina in 1749, Blount served in the Continental Congress 1782–1783 and 1786–1787. In 1790, President Washington appointed him governor of the newly formed Territory South of the River Ohio, formerly part of North Carolina. While governor, Blount was also Indian affairs superintendent and negotiated, among others, the Treaty of the Holston with the Cherokee. His new government faced for- midable problems, intensified by conflicts created by European/Indian contact. In 1795, Blount called a constitutional convention to organize the state, and Tennessee entered the Union the next year. Blount repre- sented the new state in the U.S. Senate, and, after expulsion from that body on a conspiracy charge, served in the state Senate. He died in 1800. John Sevier 1796–1801; 1803–1809, Democratic-Republican Born in Virginia in 1745, Sevier as a young man was a successful merchant. Coming to a new settlement on the Holston River in 1773, he was one of the first white settlers of Tennessee. He was elected governor of the state of Franklin at the end of the Revolutionary War and as such became the first governor in what would be Tennessee. When statehood was attained in 1796, Sevier was elected its first governor. He served six terms totaling twelve years. While governor, he negotiated with the Indian tribes to secure additional lands for the new state and opened State of Tennessee new roads into the area to encourage settlement. At the close of his sixth term, he was elected to the state Senate and then to Congress. -

Native Nations and the Convention

Boston College Law School Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School Boston College Law School Faculty Papers 4-1-2021 Without Doors: Native Nations and the Convention Mary Sarah Bilder Boston College Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/lsfp Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Indigenous, Indian, and Aboriginal Law Commons, and the Legal History Commons Recommended Citation Mary Sarah Bilder. "Without Doors: Native Nations and the Convention." Fordham Law Review 89, no.5 (2021): 1707-1759. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College Law School Faculty Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WITHOUT DOORS: NATIVE NATIONS AND THE CONVENTION Mary Sarah Bilder* Wednesday last arrived in this city, from the Cherokee nation, Mr. Alexander Droomgoole, with Sconetoyah, a War Captain, and son to one of the principal Chiefs of that nation. They will leave this place in a few days, for New-York, to represent to Congress some grievances, and to demand an observance of the Treaty of Hopewell, on the Keowee, which they say has been violated and infringed by the lawless and unruly whites on the frontiers. We are informed that a Choctaw King, and a Chickasaw Chief, are also on their way to the New-York, to have a Talk with Congress, and to brighten the chain of friendship. —Pennsylvania Mercury, June 15, 17871 INTRODUCTION The Constitution’s apparent textual near silence with respect to Native Nations is misleading. -

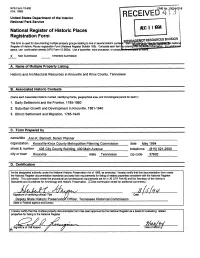

Historic and Architectural Resources in Knoxville and Knox County, Tennessee

NPS Form 10-900 (Oct. 1990) RECEIVED United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form MERAGENCY RESOURCES DIVISION This form is used for documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contex s See instru^W* ffi/itow«ivQcMnpfaffiffie Nationa Register of Historic Places registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16B). Complete each item space, use continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or comp X New Submission Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Listing Historic and Architectural Resources in Knoxville and Knox County, Tennessee B. Associated Historic Contexts (Name each Associated Historic Context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each>) 1. Early Settlement and the Frontier, 1785-1860 2. Suburban Growth and Development in Knoxville, 1861-1940 3. Ethnic Settlement and Migration, 1785-1940 C. Form Prepared by name/title Ann K. Bennett, Senior Planner organization Knoxville-Knox County Metropolitan Planning Commission date May 1994 street & number 403 City County Building, 400 Main Avenue__________ telephone (615)521-2500 city or town Knoxville state Tennessee zip code 37902_____ D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for listing of related properties consistent with the -

James P. H. Porter. (To Accompany Bill H.R. No. 264)

University of Oklahoma College of Law University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons American Indian and Alaskan Native Documents in the Congressional Serial Set: 1817-1899 2-25-1846 James P. H. Porter. (To accompany bill H.R. no. 264). Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.ou.edu/indianserialset Part of the Indian and Aboriginal Law Commons Recommended Citation H.R. Rep. No. 329, 29th Cong., 1st Sess. (1846) This House Report is brought to you for free and open access by University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in American Indian and Alaskan Native Documents in the Congressional Serial Set: 1817-1899 by an authorized administrator of University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 29th CoNGREss, Rep. No. 329. Ho. oF REP. 1st Session. JAMES P. H. PORTER. l Tq accompany bill H. R. No. 264.] FEBRUARY 25, 1846. Mr. CocKE, from the Committee on Invalid Pensions, made the following REPORT: The Committee on lnvalid Pensions, to whom were referred tiLe petition and papers of James P. H Porter, having had the same under con sideration, beg leave to submit the following report : That in the year 1813, Major Porter, the petitioner in this case, served a campaign as major of cavalry in the Creek war under Brig. Gen. White. When he entered the service aforesaid, he was engaged in a lucrative prac tice of the law in the State of Tenaessee. He possessed a strong and vig orous constitution, and was in the enjoyment of fine health. -

Descendants of Adam White

Descendants of Adam White Generation No. 1 1. ADAM1 WHITE was born Abt. 1627 in Scotland, and died December 19, 1708 in Bushmills, County Antrim, Ireland. Notes for ADAM WHITE: Scottish and Irish sources reveal the following data concerning the life and ministry of the Reverend Adam White, putative ancestor of Moses and Hugh White of Delaware and Pennsylvania. Adam White was born in Scotland circa 1620-1625. He was educated at Glasgow University and received a Master of Arts degree in 1648. He was ordained - Clondevaddock (Fannet), 1654. He received 100 pounds a year from the Proctorate, 1655. Deposed for non-conformity, 1661, but continued to minister. Excommunicated and imprisoned in Lifford, 1664-1670 for disobeying a summons issued by Leslie, Bishop of Raphoe. Resigned September 18, 1672. Installed Ardstraw. Fled to Scotland, 1688. Resigned 1692. Installed Billy, near Dunluce, 1692. Died December 19, 1708. The exodus from Scotland to Ulster continued for some years. In July, 1635, a James Blair of Ayrshire, wrote: "Above ten thousand persons, have , within two years past, left this country - between Aberdeen and Inverness, and gone over to Ireland. They have come by the hundred, through this town, and three hundred shipped together on one tide." The founders of the Presbyterian Church in Ulster, were Clergymen, who took refuge, driven from Scotland and England, by the persecuting spirit, abroad then, against Puritans. But in 1637, the Calvinists Confession of Faith was altered. Bishops tinged with Puritanism, were deposed. High churchmen were placed in their stead. Conformity to the Established Church was enforced with pains and penalties. -

An Ethno-Historical Account of the African American Community in Downtown Knoxville, Tennessee Before and After Urban Renewal

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 12-2015 AN ETHNO-HISTORICAL ACCOUNT OF THE AFRICAN AMERICAN COMMUNITY IN DOWNTOWN KNOXVILLE, TENNESSEE BEFORE AND AFTER URBAN RENEWAL Anne Victoria University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Anthropology Commons, Arts and Humanities Commons, Human Geography Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Recommended Citation Victoria, Anne, "AN ETHNO-HISTORICAL ACCOUNT OF THE AFRICAN AMERICAN COMMUNITY IN DOWNTOWN KNOXVILLE, TENNESSEE BEFORE AND AFTER URBAN RENEWAL. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2015. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/3613 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Anne Victoria entitled "AN ETHNO-HISTORICAL ACCOUNT OF THE AFRICAN AMERICAN COMMUNITY IN DOWNTOWN KNOXVILLE, TENNESSEE BEFORE AND AFTER URBAN RENEWAL." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in Anthropology. Bertin M. -

Chocolate City Way up South in Appalachia: Black Knoxville at the Intersection of Race, Place, and Region

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 5-2019 Chocolate City Way Up South in Appalachia: Black Knoxville at the Intersection of Race, Place, and Region Enkeshi Thom El-Amin University of Tennessee Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Recommended Citation Thom El-Amin, Enkeshi, "Chocolate City Way Up South in Appalachia: Black Knoxville at the Intersection of Race, Place, and Region. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2019. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/5340 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Enkeshi Thom El-Amin entitled "Chocolate City Way Up South in Appalachia: Black Knoxville at the Intersection of Race, Place, and Region." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Sociology. Michelle Christian, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Victor Ray, Paul K. Gellert, Michelle Brown, Jessica Grieser Accepted for the Council: -

Metropolitan Planning Commission Annual Report

KNOXVILLE • KNOX COUNTY METROPOLITAN PLANNING COMMISSION ANNUAL REPORT FY 04-05 PLANNING COMMISSIONERS FINANCIAL INFORMATION UNAUDITED FINANCIAL INFORMATION Susan Brown C. Randy Massey Trey Benefi eld Art Clancy III Herbert Donaldson Sr. The Planning Chair Vice Chair 2002-2006 2004-2008 1998-2008 FY Ending June 30, 2005 Commission is an 1999-2007 2002-2006 advisory board made up FY 04/05 Actual of 15 citizens— Budget Unaudited Fees and Charges .................................................................$434,168 .......................................................$469,690 seven appointed by Federal Government .............................................................1,014,121 .........................................................666,690 the city mayor and State of Tennessee ..................................................................213,279 .........................................................204,778 eight appointed by the City of Knoxville .......................................................................692,650 .........................................................692,650 county mayor. These City of Knoxville - contracts1 ......................................................45,000 ...........................................................45,000 volunteers come from a Knox County ............................................................................724,738 .........................................................724,738 variety of backgrounds Knox County - contracts2 ...........................................................59,484