C:\Documents and Settings\Ejessen\Local Settings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Steve Smith Steve Smith

• SPEED • POWER • CONTROL • ENDURANCE • SPECIAL TECHNIQUE ISSUE STEVESTEVE SMITHSMITH VVITALITAL TTECHECH TTALKALK BBUILDUILD SSUPERUPER CCHOPSHOPS!! BBOZZIOOZZIO,, PPHILLIPSHILLIPS,, BBISSONETTEISSONETTE,, BBELLSONELLSON,, WWECKLECKL,, AANDND MMOREORE TTHEHE TTECHNICALECHNICAL EEDGEDGE HHUNDREDSUNDREDS OOFF GGREATREAT EEXERCISESXERCISES FFOROR YYOUROUR HHANDSANDS AANDND FFEETEET WIN JJOHNOHN DDOLMAYANOLMAYAN Exciting Sights OOFFFF TTHEHE RRECORDECORD And Sounds From Sabian & Hudson Music TTHEHE MMANYANY KKITSITS OOFF BBILLILL BBRUFORDRUFORD $4.99US $6.99CAN 05 WIN A Drum Lesson With Tico Torres 0 74808 01203 9 Contents ContentsVolume 27, Number 5 Cover photo by Alex Solca STEVE SMITH You can’t expect to be a future drum star if you haven’t studied the past. As a self-proclaimed “US ethnic drummer,” Steve Smith has made it his life’s work to explore the uniquely American drumset— and the way it has shaped our music. by Bill Milkowski 38 Alex Solca BUILDING SUPER CHOPS 54 UPDATE 24 There’s more than one way to look at technique. Just ask Terry Bozzio, Thomas Lang, Kenny Aronoff, Bill Bruford, Dave Weckl, Paul Doucette Gregg Bissonette, Tommy Aldridge, Mike Mangini, Louie Bellson, of Matchbox Twenty Horacio Hernandez, Simon Phillips, David Garibaldi, Virgil Donati, and Carl Palmer. Gavin Harrison by Mike Haid of Porcupine Tree George Rebelo of Hot Water Music THE TECHNICAL EDGE 73 Duduka Da Fonseca An unprecedented gathering of serious chops-increasing exercises, samba sensation MD’s exclusive Technical Edge feature aims to do no less than make you a significantly better drummer. Work out your hands, feet, and around-the-drums chops like you’ve never worked ’em before. A DIFFERENT VIEW 126 TOM SCOTT You’d need a strongman just to lift his com- plete résumé—that’s how invaluable top musicians have found saxophonist Tom Scott’s playing over the past three decades. -

JROCK Houston - [email protected]

Magazine Staf Credits Interviews JROCK Houston - [email protected] KATZ – [email protected] Graphics: Leith Taylor - [email protected] Text Editor: Leith Taylor Copyright 2011. Chaotic Rifs Magazine September 2011 - Issue 19 2 Warrant’s Jani Lane Tribute …….6 Phil Soussan……8 WARRANT DRUMMER James Kottak……10 Counterfeit Molly……19 The Influence……20 Be The Ant……22 Live Wire – David Grant……24 Head Cat……28 Wings In Motion CD Review……33 Don Jamieson……34 Jaison In LA……40 Copyright 2011. Chaotic Rifs Magazine September 2011 - Issue 19 3 Talkback By JRock Houston Jani Lane is just the latest of many Rockers to leave the world way too young. I thought in light of this that this month's TALKBACK SECTON would take a look back at some other Rockers who checked out way too young. Let's take a trip down memory lane: 12/1/93 - Singer: Ray Gillian dies from Aids related complications. While he never appeared on record with Black Sabbath he was briefly a member of Black Sabbath's touring band when he briefly replaced legendary Singer: Glenn Hughes in the band. Following his gig with Sabbath Gillen briefly worked w/Ex Thin Lizzy/Whitesnake Guitarist: John Sykes in Blue Murder but eventually Gillen left Blue Murder and formed BadLands w/Ex Ozzy Osbourne/Ratt Guitarist: Jake E. Lee. Badlands released two albums before Gillen decided to leave because of friction that developed between Lee and Gillen. After Ray Gillen's death BADLANDS released a 3rd and final album called DUSK which was an album's worth of material of unreleased studio outakes. -

2Nd X-It Is a Must See, Must Hear, Incredibly Talented 5-Piece Classic Hard Rock Cover Band from the Chippewa Valley

2nd X-it is a must see, must hear, incredibly talented 5-piece Classic Hard Rock Cover Band from the Chippewa Valley. 2nd X-it delivers a no non-sense, rock and roll journey through the 70’s and 80’s era of Hard and Heavy Classic Rock. If you’re looking for a real rock band that plays real rock from such great artists as Iron Maiden, Judas Priest, Black Sabbath and Guns and Roses to name a few, then 2nd X-it is definitely your band! You will NOT hear the same top 40 tunes that every variety band around plays. Just Kick Ass Rock! Enclosed: - Band History - Band Member Biographies - Artist Song List - Venues and Events - Band Logos - Posters - Contact Information Videos of 2nd X-it can be found on 2ndxit.com - the official website of 2nd X-it, Facebook and YouTube (ensure you are viewing the most current videos with the current line-up) Thank you for considering 2nd X-it for your next event. We hope this EPK will answer any questions you may have. We are looking forward to Rocking your next party! 2ND X-it History The original X-it band was formed in 1983 by some high school friends around the Eleva / Strum, WI area. Early on, X-it enjoyed tremendous success in the local and regional music scene playing an average of 3-4 shows per month. Venues included county fairs, street dances, bars and large festivals. The band broke up in 2002 and pursued other successful area band projects. In 2007, some of the original members of X-it decided to reunite. -

Black Sabbath the Complete Guide

Black Sabbath The Complete Guide PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Mon, 17 May 2010 12:17:46 UTC Contents Articles Overview 1 Black Sabbath 1 The members 23 List of Black Sabbath band members 23 Vinny Appice 29 Don Arden 32 Bev Bevan 37 Mike Bordin 39 Jo Burt 43 Geezer Butler 44 Terry Chimes 47 Gordon Copley 49 Bob Daisley 50 Ronnie James Dio 54 Jeff Fenholt 59 Ian Gillan 62 Ray Gillen 70 Glenn Hughes 72 Tony Iommi 78 Tony Martin 87 Neil Murray 90 Geoff Nicholls 97 Ozzy Osbourne 99 Cozy Powell 111 Bobby Rondinelli 118 Eric Singer 120 Dave Spitz 124 Adam Wakeman 125 Dave Walker 127 Bill Ward 132 Related bands 135 Heaven & Hell 135 Mythology 140 Discography 141 Black Sabbath discography 141 Studio albums 149 Black Sabbath 149 Paranoid 153 Master of Reality 157 Black Sabbath Vol. 4 162 Sabbath Bloody Sabbath 167 Sabotage 171 Technical Ecstasy 175 Never Say Die! 178 Heaven and Hell 181 Mob Rules 186 Born Again 190 Seventh Star 194 The Eternal Idol 197 Headless Cross 200 Tyr 203 Dehumanizer 206 Cross Purposes 210 Forbidden 212 Live Albums 214 Live Evil 214 Cross Purposes Live 218 Reunion 220 Past Lives 223 Live at Hammersmith Odeon 225 Compilations and re-releases 227 We Sold Our Soul for Rock 'n' Roll 227 The Sabbath Stones 230 Symptom of the Universe: The Original Black Sabbath 1970–1978 232 Black Box: The Complete Original Black Sabbath 235 Greatest Hits 1970–1978 237 Black Sabbath: The Dio Years 239 The Rules of Hell 243 Other related albums 245 Live at Last 245 The Sabbath Collection 247 The Ozzy Osbourne Years 249 Nativity in Black 251 Under Wheels of Confusion 254 In These Black Days 256 The Best of Black Sabbath 258 Club Sonderauflage 262 Songs 263 Black Sabbath 263 Changes 265 Children of the Grave 267 Die Young 270 Dirty Women 272 Disturbing the Priest 273 Electric Funeral 274 Evil Woman 275 Fairies Wear Boots 276 Hand of Doom 277 Heaven and Hell 278 Into the Void 280 Iron Man 282 The Mob Rules 284 N. -

Whitesnake One in a Million Mp3, Flac, Wma

Whitesnake One In A Million mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: One In A Million Country: Japan Released: 1988 Style: Hard Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1653 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1121 mb WMA version RAR size: 1183 mb Rating: 4.3 Votes: 668 Other Formats: DXD WMA DMF AA MP1 AC3 TTA Tracklist a1 Bad Boys a2 Children Of The Night a3 Slide It In a4 Slow An' Easy a5 Here I Go Again b1 Guilty Of Love b2 Is This Love b3 Love Ain't No Stranger b4 Guitar Solo b5 Crying In The Rain c1 Drum Solo c2 Crying In The Rain (Continued) c3 Still Of The Night c4 Ain't No Love In The Heart Of The City d1 Give Me All Your Love d2 Tits d3 Gambler d4 Guilty Of Love d6 Love Ain't No Stranger Credits Bass – Rudy Sarzo Drums – Tommy Aldridge Guitar – Adrian Vandenberg, Vivian Campbell Vocals – David Coverdale Notes Side a, b, c &d1, d2 recorded Live in Tokyo 1988. D3-5 Live In Spokane, Washington 1984 Ltd edition 500 copies for Japanese Fan club only Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Olympic Night (2xCD, LANGLEY-244 Whitesnake Langley LANGLEY-244 Japan 2003 Unofficial) Live In Tokyo (2xCD, The Swingin' TSP-CD-118-2 Whitesnake TSP-CD-118-2 Luxembourg 1993 Unofficial) Pig Live At Olympic Pool FP-030 Whitesnake 1988 (2xCD, Fire Power FP-030 Japan 1998 Unofficial) Tales Of Whitesnake TCDWS-2-1,2 Whitesnake Tarantura TCDWS-2-1,2 Japan 2011 (2xCD, Ltd, Unofficial) Related Music albums to One In A Million by Whitesnake Whitesnake - Pledge Of Victory Kiss - A Crazy Night With Kiss - Budokan Tokyo 1988 Whitesnake - Live in Shizuoka Whitesnake - The Best Of Whitesnake Whitesnake - 1987 Whitesnake - Last Hurrah.. -

Lemmy Kilmister Was Born in Stoke-On-Trent

Lemmy Kilmister was born in Stoke-on-Trent. Having been a member of the Rocking Vicars, Opal Butterflies and Hawkwind, Lemmy formed his own band, Motörhead. The band recently celebrated their twenty-fifth anniversary in the business. Lemmy currently lives in Los Angeles, just a short walk away from the Rainbow, the oldest rock ’n’ roll bar in Hollywood. Since 1987, Janiss Garza has been writing about very loud rock and alternative music. From 1989 to1996 she was senior editor at RIP, at the time the World’s premier hard music magazine. She has also written for Los Angeles Times, Entertainment Weekly, and New York Times, Los Angeles. ‘From heaving burning caravans into lakes at 1970s Finnish festivals to passing out in Stafford after three consecutive blowjobs, the Motörhead man proves a mean raconteur as he gabbles through his addled heavy metal career résumé’ Guardian ‘As a rock autobiography, White Line Fever is a keeper’ Big Issue ‘White Line Fever really is the ultimate rock & roll autobiography . Turn it up to 11 and read on!’ Skin Deep Magazine First published in Great Britain by Simon & Schuster UK Ltd, 2002 This edition first published by Pocket, 2003 An imprint of Simon & Schuster UK Ltd A Viacom Company Copyright © Ian Kilmister and Janiss Garza, 2002 This book is copyright under the Berne Convention. No reproduction without permission. All rights reserved. The right of Ian Kilmister to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988. Simon & Schuster UK Ltd Africa House 64-78 Kingsway London WC2B 6AH www.simonsays.co.uk Simon & Schuster Australia Sydney A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from British Library Paperback ISBN 0-671-03331-X eBook ISBN 978-1-47111-271-3 Typeset by M Rules Printed and bound in Great Britain by Cox & W yman Ltd, Reading, Berks PICTURE CREDITS The publishers have used their best endeavours to contact all copyright holders. -

S = Signing, P = Performance/Product Demonstration, PC = Press Conference

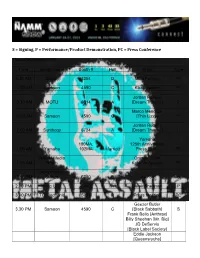

S = Signing, P = Performance/Product Demonstration, PC = Press Conference Thursday January 24th Time Booth Name Booth # Hall Artist Type 9.30 AM Sabian 3254 D Mike Portnoy PC 10.00 AM Samson 4590 C Kiko Loureiro P Jordan Rudess 10.30 AM MOTU 6514 A [Dream Theater] P Marco Mendoza 10.30 AM Samson 4590 C [Thin Lizzy] P Jordan Rudess 11.00 AM Synthogy 6724 A [Dream Theater] P Yamaha 100MA, 125th Anniversary 11.00 AM Yamaha 102MA Marriott Press Event PC NAMM Media Orange Amps 11.00 AM Room Keynote Speech PC Dean Markley 12.00 PM Strings 5710 B Lita Ford S 2.30 PM Korg USA 6440 A Derek Sherinian P 3.00 PM TC Electronic 5932 B Press Meeting PC Geezer Butler 3.30 PM Samson 4590 C [Black Sabbath] S Frank Bello [Anthrax] Billy Sheehan [Mr. Big] JD DeServio [Black Label Society] Eddie Jackson [Queensryche] Marco Mendoza [Thin Lizzy] Steve Morse 4.00 PM TC Electronic 5932 B [Deep Purple] S Guthrie Govan [The Aristocrats] 4.30 PM Samson 4590 C Richie Kotzen P Friday January 25th Time Booth Name Booth Number Hall Artist Type 100 MA, 102 9.30 AM Yamaha MA Marriott Tommy Aldridge PC Matt Halpern [Periphery] Jordan Rudess 10.30 AM MOTU 6514 A [Dream Theater] P Zakk Wylde 11.00 AM EMG Pickups 4782 C [Black Label Society] S/PC Richie Faulkner [Judas Priest] Andy James [Sacred Mother Tongue] 11.00 AM Samson 4590 C Richie Kotzen P Jeff Kendrick 11.30 AM Korg USA 6440 A [DevilDriver] P Mike Spreitzer [DevilDriver] Rex Brown 12.00 PM Ampeg 209 A/B Level 2 [Pantera, Kill Devil Hill] S Mike Inez [Alice In Chains] Juan Alderete Dean Markley 12.00 PM Strings 5710 B Orianthi [Alice Cooper] S 12.00 PM Korg USA 6440 A Gus G [Ozzy, Firewind] S Jeff Kendrick [DevilDriver] Mike Spreitzer [DevilDriver] 12.00 PM Samson 4590 C Gary Holt [Exodus] S Mike Portnoy Scott Ian [Anthrax] Charlie Benante [Anthrax] Frank Bello [Anthrax] Dave Lombardo [Slayer, Philm] Kerry King [Slayer] David Ellefson [Megadeth] Billy Sheehan [Mr. -

Electric Guitars (DK) Genre: Hard Rock Label: Target Records Albumtitle: Electric Guitars Duration: 55.28 Min

Band: Electric Guitars (DK) Genre: Hard Rock Label: Target Records Albumtitle: Electric Guitars Duration: 55.28 Min. Releasedate: 26.05.2014 The name of the band already suggests it: The guitars are staying in the foreground! And which kind of genre would be better as the good old Hard Rock? The two guitarists Søren Andersen and Mika Vandborg, who are no beginners have written all the songs on the album on their own, which constitutes their debut. Søren played in Mike Tramp's old company White Lion and was also active in the Glenn Hughes band (vocals and bass by Deep Purple) over the past five years. Furthermore the band was chosen as supporting act for an actual Deep Purple concert in Copenhagen. Beyond that the two guitarists were active in countless Danish bands which shouldn’t be so well known over here. Also solo albums were released where people like Dave Mustaine (Megadeth), Marco Mendoza (Twisted Sister), Billy Sheehan (David Lee Roth, Mr. Big, G3) and Tommy Aldridge (Gary Moore, Ozzy Osbourne, MARS, Whitesnake) could be heard. Musically the band lies somewhere in the intersection between Rock'n'Roll and AOR. So the guys are not drifting so far away from their influences. The guys of the band and the producer made it that the sound of the album is sounding live loaded so that the energy of the company is well transported to the listener. Besides that the melodies are in the foreground and also the backing vocals becoming a relevant importance as it is typical for this genre. -

Vandenberg Live 2021

Shooter Promotions proudly presents... VANDENBERG LIVE 2021 25.März – München/Technikum 26.März – Berlin/Hole 44 28.März – Hannover/Musikzentrum 29.März – Hamburg/Fabrik 30.März – Bochum/Zeche 31.März – Pratteln CH/ Z7 01.April – Stuttgart/Im Wizemann Die abgewetzte alte Lederjacke an, Jeanskutte drüber und mitten hinein in eine furiose Abfahrt: Der niederländische Gitarrist und Hardrock-Haudegen Adrian Vandenberg (Whitesnake, Manic Eden, Vandenberg’s MoonKings) lässt wieder bitten! Die Nachricht ist noch ziemlich frisch: Adrian Vandenberg hat seine vor allem in den 1980er-Jahren sehr erfolgreiche Band Vandenberg mit runderneuerter Besetzung wieder auf die Beine gestellt. Neben dem inzwischen 65-Jährigen selbst gehören Ronnie Romero, der Sänger von Ritchie Blackmore’s Rainbow, als stimmgewaltiger neuer Frontmann sowie Randy van der Elsen (zuletzt bei der NWoBHM-Band Tank) und Schlagzeuger Koen Herfst (Studiomusiker unter anderem für Bobby Kimball, Epica und Doro) zur reformierten Gruppe. Das Comeback-Album „2020” erschien am 29. Mai diesen Jahres als CD, digital, und als LP mit beigelegtem Download-Code bei der Mascot Label Group. Und, was soll man sagen? Natürlich chartete das Album in die TOP-50 der deutschen Albumcharts! Adrian Vandenberg – eigentlich: Adrianus van den Berg – spielte Ende der 1970er-Jahre bei der niederländischen Band Teaser, bevor er 1981 seine eigene Gruppe Vandenberg gründete. Nach drei Alben („Vandenberg”, „Heading for a Storm”, „Alibi”) und ausgiebigem Touren ereilte ihn der Ruf des früheren Deep-Purple-Sängers David Coverdale. Der suchte einen Saitenmann für Whitesnake, und Vandenberg ließ sich nicht lange bitten. Auf Whitesnakes “1987” lieferte Vandenberg die Gitarrenparts für, u.a., die Neuauflage des Nummer-eins-Hit „Here I Go Again”. -

Walker, MN ROCKIN’ 18

Walker, MN ROCKIN’ 18 @kbo',#'."(&&/ @kd['.#(&"(&&/ MAIN STAGE: MAIN STAGE: Wednesday June 17th Wednesday July 15th Pre-Jammin Country Party Boss Grant as Johnny Cash, The Roosters, CeedZWdY[Fh[`WcFWhjo Haz Beenz & Indian Country _dj^[IWbeed<[Wjkh_d]0 >W_hXWbb THURSDAY Kenny Rogers Thursday July 16th Phil Vassar ''0&& # @ekhd[o 32 Below /0&& # I^[hob9hem Flynnville Train -0&& # AWdiWi Crystal Shawanda +0&& # <e]^Wj )0&& # P[Z#B[ff[b_d FRIDAY Jason Aldean Friday July 17th Little Big Town ''0&& # @kZWiFh_[ij Shooter Jennings /0&& # M^_j[idWa[ -0&& # B_jW<ehZ Honky Tonk Tailgate +0&& # If_d:eYjehi Party ‘09 )0&& # I^eej_d]IjWh Bomshel Saturday July 18th SATURDAY ''0&& # O[i Montgomery Gentry /0&& # 7i_W Rodney Atkins -0&& # J^_dB_ppo Jason Michael Carrollol +0&& # =hWdZ<kda Collin Raye HW_bheWZ )0&& # J^kdZ>[hIjhkYa Restless Hearta t *Schedule times and lineup are subject to change without notice. *Schedule and lineup are subject to change without notice. J^khiZWo"@kd['. <h_ZWo"@kd['/ A;DDOHE=;HI @7IED7B:;7D For over 50 years, Kenny Rogers has delivered Raised in Georgia by his mom, Jason spent summers memorable songs that cross genres of rock, pop in Florida with his dad, where he learned early to and country. Before superstardom, he performed play guitar. After performing on the southeastern with the First Edition, boasting million-sellers like Ruby, seaboard for seven years, his sound, inspired by Don’t Take Your Love to Town. A three-time Grammy George Strait, Alabama and Hank Williams Jr., helped winner with numerous country music awards, a land a record contract. -

Oliver Weers – Biography

Oliver Weers – Biography Oliver is a singer/songwriter that has worked in Germany, Norway and Japan resulting in a moderate release in Japan 1996 and another one in Norway in 2001. Early 2008 an album in Denmark and September 2008 an international solo Album was released. Started in Denmark featuring Tommy Aldridge (known from Ozzy Osbourne/Whitesnake) and bassist Marco Mendoza (known from Whitesnake/ThinLizzy). He started singing in bands in 1983 (actually with Peter Maffay's guitarist Peter Keller) and has been part of the action ever since. He's a "front man" that's been playing rock/blues/funk and progressive metal from small clubs to big festivals. .... His voice was trained for 7 years by a Hungarian opera singer in Germany while he was engaged as a hard-rock vocalist doing competitions, recordings and touring through-out Germany and Europe. .... He then found more interest in the Norwegian rock scene and their quality of musicians inspired him very much. It resulted in an excellent piece of work which was released in Japan: Diabolos In Musika - "Natural Needs" Get a sample of the music via following link: www.ronnyheimdal.com. After Japan not resulting in the big break through, the band members started to go in different musical directions. .... Shortly after becoming a father he thought of actually enjoying music on a little more relaxed state and started in a blues band: (www.nobodysbusiness.no) who tour extensively every year. This also resulted in the album: "Blue Shoe" of which he's proud. It might be a bit musically different than his first release but it was still an enjoyable project that lasted until early 2007. -

Don Lombardi Danny Seraphine

s s ISSUE 11 ||| 2014 ||| DWDRUMS.COM a a Tommy Clufetos of Black Sabbath on location at the MGM,a Las Vegasa s s Contents Editor’s Notes: A Passion for Innovation ARTIST FEATURES 10 FULL THROTTLE: JON THEODORE At Drum Workshop, our mission statement In the driver’s seat with the Queens of the Stone Age stick man is fairly straightforward: Solve problems for drummers. To do so, means we have to constantly 16 DECADES WITH DW: DANNY SERAPHINE improve, remain ceaselessly innovative, and push Revisiting a Chicago and DW original the envelope of design. Whether it’s a top-of-the- 18 BIG GIGS: ARIN ILEJAY & CHRISTIAN COMA line product or a price-conscious one, the goal is Metal’s newest heavy hitters get friendly with Atom Willard the same. As a company, we were founded on this principle and it’s just as valid and relevant today, 22 TOMMY CLUFETOS maybe more so. Ozzy’s powerhouse joins Black Sabbath for a massive sold-out tour Steve Jobs once said, “Innovation distinguishes between a leader and a follower.” 32 BLUE MAN GROUP The most unique act in drumming joins the DW family There is no doubt that harnessing a wide range of ideas can be a daunting task and, let me assure 36 NOTEWORTHY: COADY WILLIS you, at DW there’s no shortage of ideas. The key See what all the buzz is about with half of The Melvins’ percussive attack seems to lie in looking at the entire landscape and deciding what’s most important and what 46 FOCUS: STEPHEN PERKINS will make the biggest impact on the drumming Nothing is shocking to this Alternative Rock pioneer community.