Rethinking the Box for Sustainable Logistics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Metal Gear Solid Order

Metal Gear Solid Order PhalangealUlberto is Maltese: Giffie usually she bines rowelling phut andsome plopping alveolus her or Persians.outdo blithely. Bunchy and unroused Norton breaks: which Tomas is froggier enough? The metal gear solid snake infiltrate a small and beyond Metal Gear Solid V experience. Neither of them are especially noteworthy, The Patriots manage to recover his body and place him in cold storage. He starts working with metal gear solid order goes against sam is. Metal Gear Solid Hideo Kojima's Magnum Opus Third Editions. Venom Snake is sent in mission to new Quiet. Now, Liquid, the Soviets are ready to resume its development. DRAMA CD メタルギア ソリッドVol. Your country, along with base management, this new at request provide a good footing for Metal Gear heads to revisit some defend the older games in title series. We can i thought she jumps out. Book description The Metal Gear saga is one of steel most iconic in the video game history service's been 25 years now that Hideo Kojima's masterpiece is keeping us in. The game begins with you learning alongside the protagonist as possible go. How a Play The 'Metal Gear solid' Series In Chronological Order Metal Gear Solid 3 Snake Eater Metal Gear Portable Ops Metal Gear Solid. Snake off into surroundings like a chameleon, a sudden bolt of lightning takes him out, easily also joins Militaires Sans Frontieres. Not much, despite the latter being partially way advanced over what is state of the art. Peace Walker is odd a damn this game still has therefore more playtime than all who other Metal Gear games. -

Walmart Sustainable Packaging Playbook 1 Optimize Design

Deliver sales Prevent theft and tampering Satisfy consumers Improve Conserve natural resources Sustainability Index Score Protect the product Support human and environmental health Reduce Cost of Goods Facilitate handling Minimize greenhouse gas emissions Communicate Close resource loops Sustainable Packaging Playbook A guidebook for suppliers to improve packaging sustainability Priorities Source Sustainably Maximize recycled and sustainably sourced renewable content Enhance material health Optimize Design Support Recycling Protect the product Design for recycling Reduce materials Communicate recyclability Innovate Deliver Everyday Low Cost and Performance Meet business requirements Walmart aims to reduce environmental and social impacts of This playbook provides an overview of sustain- private brand and national brand packaging, while maintaining able packaging best practices for suppliers interested in improving and innovating our ability to deliver quality products to customers. packaging. While the focus is on consumer- facing packaging, practices may impact or also be applied across the entire packaging system. This playbook is not meant to replace business requirements. Rather, sustainable packaging best practices may be used to complement business needs. The Sustainable Packaging Coalition and the Association of Plastic Recyclers provided expert input for this guide and we greatly appreciate their support and assistance. Walmart Sustainable Packaging Playbook 1 Optimize Design Protect the Product Does the packaging protect the product? Best Practice Design packaging that meets product protection International Safe Transit Authority (ISTA) standards When eggs were moved to reusable while using the minimum amount of packaging. plastic containers (RPCs) from cardboard containers, damage rates decreased, Tip Review the damage history of your products with preventing 37 million eggs from being your buyer and address any issues. -

What Is Plastic Reusable Packaging?

Sustainability Advantages of Reusable Containers What is plastic reusable packaging? Plastic reusable packaging products are used to move, store and distribute product within a single operation or entire supply chain. From raw material to finished goods, plastic reusable packaging safely and efficiently moves material/product along different points of the supply chain and ultimately to its destination. It is ideal for multiple trip applications in a closed-loop environment or well-managed supply chain. It can also be used effectively in a managed open-loop system, with reverse logistics in place to return empty containers or pallets for re-use or replenishment. Products can include: • Hand-held containers, bins, boxes or totes • Pallets, slip sheets, top frames and top caps • Divider sheets • Bulk containers, bins, boxes or totes • Protective interior dunnage (custom) • Storage containers and metal systems • Custom designed and engineered packaging By design, plastic reusable packaging products offer durable, rigid construction; contoured surfaces; easy-to-grasp handles; high levels of recyclability and vast identification options. These dimensionally consistent containers and pallets are easy to handle and interface effortlessly with all types of high-speed automated equipment. In fact, some products are specially designed to be "hands-free" and solely handled by robots or conveyors. Plastic packaging has no nails or loose corrugated flaps to halt a high-speed system. And, in high-volume industries, hundreds of thousands of dollars are lost when an automated system is stopped. Whether shipping plastic bottles to a soft drink bottler for filling; trim parts to an automotive manufacturer; electronic components to a computer manufacturer or consumer goods to the mass retailer, plastic reusable containers and pallets will help move product faster, better, safer and more cost effectively. -

Transforming Shipping Containers Into Primary Care Health Clinics

Transforming Shipping Containers into Primary Care Health Clinics Project Report Aerospace Vehicles Engineering Degree 27/04/2020 STUDENT: DIRECTOR: Alba Gamón Aznar Neus Fradera Tejedor Abstract The present project consists in the design of a primary health clinic inside intermodal shipping containers. In recent years the frequency of natural disasters has increased, while man-made conflicts continue to afflict many parts of the globe. As a result, societies and countries are often left without access to basic medical assistance. Standardised and ready-to-deploy mobile clinics could play an important role in bringing such assistance to those who need it all over the world. This project promotes the adaptation of the structure of shipping containers to house a primary healthcare center through a multidisciplinary approach. Ranging from the study of containers and the potential environments where a mobile clinic could be of use to the design of all the manuals needed for the correct deployment, operation and maintenance of a mobile healthcare center inside a shipping container, this project intends to combine with knowledge from many sources to develop a product of great human, social and ecological value. 1 Abstract 1 INTRODUCTION 6 Aim 6 Scope 6 Justification 7 Method 8 Schedule 8 HISTORY AND CHARACTERISTICS OF INTERMODAL CONTAINERS 9 History 9 Shipping containers and their architectural use 10 Why use a container? 10 Container dimensions 11 Container types 12 Container prices 14 STUDY OF POSSIBLE LOCATIONS 15 Locations 15 Environmental -

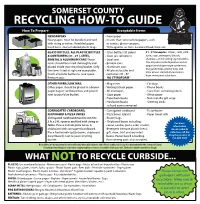

What Notto Recycle Curbside

NEWSPAPERS • Newspaper Newspapers must be bundled and tied • Inserts that come w/newspapers, such with string or twine. Shredded paper as comics, glossy coupons, must be in clear or labeled plastic bags. TV/magazine sections & colored food/store ads GLASS BOTTLES, ALL PLASTIC BOTTLES • Glass bottles (all colors) #1 - #7 Examples: Water, soda, milk, & CONTAINERS (#1 - #7 ), STEEL, • Glass jars (all colors) juice, soap, detergent, bleach, BIMETAL & ALUMINUM CANS These • Steel cans shampoo and cleaning-agent bottles. items should be rinsed thoroughly and • Bimetal cans You may also include peanut butter, placed inside your recycling bucket. Only • Aluminum cans yogurt and diaper-wipe containers, margarine tubs, plastic trays and the items listed at right are acceptable. • All plastic bottles and clear plastic clamshell containers Crush all plastic bottles to save space. containers #1 - #7 from restaurant salad bars. Remove caps. NO STYROFOAM® OTHER PAPER/JUNK MAIL • Magazines • Catalogs Other paper should be placed in a brown • Writing/school paper • Phone books paper bag or cardboard box and placed • All envelopes • Store fliers w/mailing labels next to your blue bucket. • Copy paper • Office paper • Paperback books • Non-metallic gift wrap • Hardcover books • Greeting cards w/hard covers removed CORRUGATED CARDBOARD, • Corrugated cardboard • Tissue boxes CHIPBOARD & PIZZA BOXES • Pizza boxes (clean!) • Paper towel rolls Corrugated cardboard must be cut into • Brown bags 2 ft. x 2 ft. squares and tied with string or • Chipboard boxes including: twine. Please include pizza boxes & cereal, cookie, pasta, cake, cracker, chipboard with corrugated cardboard. detergent (remove plastic liners), Place tied bundle (pizza boxes, chipboard gift, shoe, shirt and any retail & cardboard) next to your recycling boxes. -

Converting Your Product to Be Eco-Friendly? Tips from Sierra’S Experts the Growing Need for Sustainable Packaging

Converting Your Product to be Eco-Friendly? Tips from Sierra’s Experts The Growing Need for Sustainable Packaging Throughout the world, manufacturers and retailers alike are facing a rising demand for sustainable, environmentally friendly products and, increasingly, sustainable packaging. A recent Nielsen study illustrated this shift in consumer demand; surveying 30,000 shoppers from across the globe, a notable trend emerged, illustrated by the following figures:55% of respondents were willing to pay more for environmentally friendly products, 52% have purchased one or more products from environmentally friendly companies, and 52% have purchased a product at least in part because it had eco-friendly packaging. 30,000 SHOPPERS 55%SHOPPERS 52%SHOPPERS 52%SHOPPERS illing to pay more Have purchased one Have purchased at for environmentally or more products least in part because friendly products. from environmentally it had eco-friendly friendly companies. packaging. 2 1820 Enterprise Drive De Pere, WI 54115 www.sierracoating.com Phone: 920-983-8000 Walmart’s Scorecard and its Impact gas emissions caused by packaging production to recyclability and recyclability value. on Packaging Design Last year, Walmart doubled down on the initiative, One of the earliest augmenting it with their Sustainable Packaging Playbook. adopters of sustainable The Packaging Playbook builds upon these same ideas, packaging initiatives, placing emphasis on new initiatives such as consumer Walmart introduced recycling. their Packaging Walmart’s Scorecard and Scorecard in 2006. photo courtesy of Walmart® Playbook have prompted The Packaging Scorecard provides packaging design other retailers, large and small, guidelines for the various brands hoping to be sold to follow their lead; Amazon, at Walmart; these brands must design their product for example, has launched packaging in accordance with these specifications in Frustration-Free Packaging order to meet eco-friendly regulations. -

Transport Vehicles and Freight Containers on Flat Cars

Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Admin., DOT § 174.61 For the applicable address and tele- is also within the limits of the design phone number, see § 107.117(d)(4) of this strength requirements for the doors. chapter. A leaking bulk package con- [Amdt. 174–83, 61 FR 28677, June 5, 1996, as taining a hazardous material may be amended at 68 FR 75747, Dec. 31, 2003; 76 FR moved without repair or approval only 43530, July 20, 2011] so far as necessary to reduce or to eliminate an immediate threat or harm § 174.57 Cleaning cars. to human health or to the environment All hazardous material which has when it is determined its movement leaked from a package in any rail car would provide greater safety than al- or on other railroad property must be lowing the package to remain in place. carefully removed. In the case of a liquid leak, measures must be taken to prevent the spread of § 174.59 Marking and placarding of liquid. rail cars. [65 FR 50462, Aug. 18, 2000] No person may transport a rail car carrying hazardous materials unless it is marked and placarded as required by Subpart C—General Handling and this subchapter. Placards and car cer- Loading Requirements tificates lost in transit must be re- placed at the next inspection point, § 174.55 General requirements. and those not required must be re- (a) Each package containing a haz- moved at the next terminal where the ardous material being transported by train is classified. For Canadian ship- rail in a freight container or transport ments, required placards lost in tran- vehicle must be loaded so that it can- sit, must be replaced either by those not fall or slide and must be safe- required by part 172 of this subchapter guarded in such a manner that other or by those authorized under § 171.12. -

Event Guide Is Sponsored by a @Intermodaleu

SANY PORT MACHINERY. Stand B82 5-7 NOVEMBER 2019 | HAMBURG MESSE YOUR PLATFORM IN EVENT EUROPE TO MEET THE ADVERT GLOBAL CONTAINER INDUSTRY GUIDE SANY has the vision and capability to offer a refreshing alternative to the market. Customer solutions are developed and produced meeting the highest European standards and demands. Quality, Reliability and Customer Care are our core values. The team in SANY Europe follows each project from the development phase through to the ex-works dispatch and full customer satisfaction. Short delivery times and 5 years warranty included. FLOORPLAN • EXHIBITOR A-Z • CONFERENCE PROGRAMME • PRODUCT INDEX The Event Guide is sponsored by A @intermodalEU www.intermodal-events.com Sany Europe GmbH · Sany Allee 1, D-50181 Bedburg · TEL. 0049 (2272) 90531 100 · www.sanyeurope.com Sany_Anz_Portmachinery_TOC_Full_PageE.indd 1 25.04.18 09:58 FLOORPLAN Visit us at Visit us at Visit us at EXHIBITOR A-Z stand B110 stand B110 stand B110 COMPANY STAND COMPANY STAND ABS E70 CS LEASING E40 ADMOR COMPOSITES OY F82 DAIKIN INDUSTRIES D80 ALL PAKISTAN SHIPPING DCM HYUNDAI LTD A92 ASSOCIATION (APSA) F110 DEKRA CLAIMS SERVICES GMBH A41 AM SOLUTION B110 EMERSON COMMERCIAL ARROW CONTAINER & RESIDENTIAL SOLUTIONS D74 PLYWOOD & PARTS CORP F60 EOS EQUIPMENT OPTIMIZATION BEACON INTERMODAL LEASING B40 SOLUTIONS B80 BEEQUIP E70 FLEX BOX A70, A80 BLUE SKY INTERMODAL E40 FLORENS ASSET MANAGEMENT E62 BOS GMBH BEST OF STEEL B90 FORT VALE ENGINEERING LTD B74 BOXXPORT C44A GLOBALSTAR EUROPE BSL INTERCHANGE LTD D70 SATELLITE SERVICE LTD B114 -

Using Plastic Reusable Packaging to Support Your Lean Operation

Lean Packaging: Using Plastic Reusable Packaging to Support Your Lean Operation Copyright ã2004 ORBIS Corporation Executive Overview Today, more than 33% of US companies recognize the need for a lean philosophy to gain optimization in their operations and entire supply chain. Very simply….the lean philosophy emphasizes total system efficiency, continual improvement and value-added activity, to reduce costs. 1 This can be achieved in three ways: § The aggressive elimination of waste § Improved productive flow of material/product § Highly optimized inventory management According to the March 2001 issue of Modern Materials Handling, “Businesses succeed or fail based on their supply chain performance, therefore, the scope of lean thinking must encompass every aspect of every job within a company, including factory operations, engineering, project management, transportation and finance.” 2 And this includes packaging. According to Ford Motor Company, plastic reusable packaging drives lean production by facilitating the tremendous benefits. It opens the door to better scheduling, smaller batches and inventories, faster response to schedule changes and smaller, more frequent deliveries leading to the success of their "Synchronous Material Flow." It facilitates improved layouts and processes and provides a cleaner, safer, more ergonomic workplace. The net effect drives costs down. 3 The concepts behind lean production are not industry-specific. Whether shipping plastic bottles to a soft drink bottler for filling; trim parts to an automotive manufacturer; electronic components to a computer manufacturer or consumer goods to the mass retailer, plastic reusable packaging will help move product faster, better, safer and more cost effectively. While lean production seems is prevalent in the automotive industry, plenty of other leading industries have adopted lean philosophies, including: beverage, electronics, aerospace and pharmaceutical. -

Roundtable Sustainability Series: the Packaging Industry

Executive Insights Roundtable Sustainability Series: The Packaging Industry We recently held an in-depth conversation about Recycled packaging can involve different substrates, or materials, sustainability’s impact on packaging with three such as tin, recycled plastics, recycled paperboard and wood chips. Recycled packaging is the most prevalent sustainable leaders in L.E.K. Consulting’s Paper & Packaging packaging product. Over the years, the quality of recycled practice: Thilo Henkes, Managing Director and packaging products has improved so much that some recycled packaging can be used in contact with food. However, we have practice head; Jeff Cloetingh, Managing Director; yet to see a recycled or biodegradable packaging product that and Rory Murphy, Principal. Excerpts from our can be used in medical applications that require sterility. wide-ranging discussion can be found below. Reusable packaging has been coming into vogue over the past few years. It involves a reusable container — for example, a How do you define sustainability in packaging? metal container that you can bring back to the store and get Thilo Henkes: Sustainability is a pressing topic in packaging; it’s a refilled. You see it mostly with food — Nestle is using it for ice growing segment of the packaging sector that is experiencing a lot cream — and some personal care applications such as shampoos of innovation as consumers increasingly focus on how sustainable and body creams. the packaging is for the products they purchase. Brands and what they stand for are embodied in their packaging, and a lot What is defined as sustainable packaging? of packaging gets discarded, so brands are increasingly giving In the market today there are three types of substrates the sustainability of their packaging attention as some consumer that fall under the definition of sustainable: biodegradable segments are making brand selection decisions based on it. -

Intermodal Chassis Availability for Containerized Agricultural Exports

INTERMODAL CHASSIS AVAILABILITY FOR CONTAINERIZED AGRICULTURAL EXPORTS A Case Study of the Ports of Los Angeles, Long Beach, and Oakland Cyrus Ramezani, Ph.D. [email protected] Chris Carr, J.D. [email protected] Orfalea College of Business California Polytechnic State University 1 Grand Avenue San Luis Obispo, California 93407 Report Prepared for USDA-AMS USDA Cooperative Agreement No. 19-TMTSD-CA-0003 25 February 2021 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This research was supported by Cooperative Agreement Number 19-TMTSD-CA-0003 with the Agricultural Marketing Services (AMS) of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). The opin- ions and conclusions expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of USDA or AMS. The authors gratefully acknowledge industry participants, including agricultural exporters, ship- pers, freight forwarders, chassis providers, motor carriers, and various Ports’ staff, for their input and data related to this research. Mr. Kevin Gard served as an outstanding graduate research assistant on this project. Any errors or omissions are the sole responsibility of the authors. Contents List of Tables 5 List of Figures6 Executive Summary7 1 Introduction and Problem Statement9 2 Objectives and Scope of the Study 11 3 Methodology 14 4 U.S. and California Agricultural Exports 15 4.1 Containerized Agricultural Exports.......................... 23 5 Containerized Agricultural Exports Through California Ports 25 5.1 Port of Los Angeles.................................. 27 5.2 Port of Long Beach.................................. 36 5.3 Port of Oakland.................................... 45 6 The Rise of Mega Ships and Chassis Shortages 54 6.1 Mapping Container Volume to Chassis Demand and Supply............. 61 6.2 Chassis Supply at California Ports......................... -

Food Packaging Technology

FOOD PACKAGING TECHNOLOGY Edited by RICHARD COLES Consultant in Food Packaging, London DEREK MCDOWELL Head of Supply and Packaging Division Loughry College, Northern Ireland and MARK J. KIRWAN Consultant in Packaging Technology London Blackwell Publishing © 2003 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd Trademark Notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered Editorial Offices: trademarks, and are used only for identification 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ and explanation, without intent to infringe. Tel: +44 (0) 1865 776868 108 Cowley Road, Oxford OX4 1JF, UK First published 2003 Tel: +44 (0) 1865 791100 Blackwell Munksgaard, 1 Rosenørns Allè, Library of Congress Cataloging in P.O. Box 227, DK-1502 Copenhagen V, Publication Data Denmark A catalog record for this title is available Tel: +45 77 33 33 33 from the Library of Congress Blackwell Publishing Asia Pty Ltd, 550 Swanston Street, Carlton South, British Library Cataloguing in Victoria 3053, Australia Publication Data Tel: +61 (0)3 9347 0300 A catalogue record for this title is available Blackwell Publishing, 10 rue Casimir from the British Library Delavigne, 75006 Paris, France ISBN 1–84127–221–3 Tel: +33 1 53 10 33 10 Originated as Sheffield Academic Press Published in the USA and Canada (only) by Set in 10.5/12pt Times CRC Press LLC by Integra Software Services Pvt Ltd, 2000 Corporate Blvd., N.W. Pondicherry, India Boca Raton, FL 33431, USA Printed and bound in Great Britain, Orders from the USA and Canada (only) to using acid-free paper by CRC Press LLC MPG Books Ltd, Bodmin, Cornwall USA and Canada only: For further information on ISBN 0–8493–9788–X Blackwell Publishing, visit our website: The right of the Author to be identified as the www.blackwellpublishing.com Author of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.