International Reaction to the Palestinian Unity Government

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pdf | 459.71 Kb

מרכז המידע הישראלי לזכויות האדם בשטחים (ע.ר.) One Big Prison Freedom of Movement to and from the Gaza Strip on the Eve of the Disengagement Plan March 2005 Researched and written by Yehezkel Lein Data coordination by Najib Abu Rokaya, Ariana Baruch, Rim ‘Odeh, Shlomi Swissa Fieldwork by Musa Abu Hashhash, Iyad Haddad, Zaki Kahil, Karim Jubran, Mazen al-Majdalawi, ‘Abd al-Karim S’adi Assistance on legal issues by Yossi Wolfson Translated by Zvi Shulman, Shaul Vardi Edited by Rachel Greenspahn Introduction “The only thing missing in Gaza is a morning line-up,” said Abu Majid, who spent ten years in Israeli prisons, to Israeli journalist Amira Hass in 1996.1 This sarcastic comment expressed the frustration of Gaza residents that results from Israel’s rigid policy of closure on the Gaza Strip following the signing of the Oslo Agreements. The gap between the metaphor of the Gaza Strip as a prison and the reality in which Gazans live has rapidly shrunk since the outbreak of the intifada in September 2000 and the imposition of even harsher restrictions on movement. The shrinking of this gap is the subject of this report. Israel’s current policy on access into and out of the Gaza Strip developed gradually during the 1990s. The main component is the “general closure” that was imposed in 1993 on the Occupied Territories and has remained in effect ever since. Every Palestinian wanting to enter Israel, including those wanting to travel between the Gaza Strip and the West Bank, needs an individual permit. In 1995, about the time of the Israeli military’s redeployment in the Gaza Strip pursuant to the Oslo Agreements, Israel built a perimeter fence, encircling the Gaza Strip and separating it from Israel. -

The Hezbollah-Israeli

The Hizbullah-Israeli War: an American Perspective Aaron David Miller It was unusual for an Israeli Prime Minster to break open a bottle of champagne in front of American negotiators at a formal meeting. But that’s exactly what Shimon Peres did. It was late April 1996, and Peres was marking the end of a bloody three week border confrontation with Hizbullah diffused only by an intense ten day shuttle orchestrated by Secretary of State Warren Christopher. Those understandings negotiated between the governments of Israel and Syria (the latter standing in for Hizbullah) would create an Israeli-Lebanese monitoring group, co-chaired by the United States and France. These arrangements were far from perfect, but contributed, along with on-again-off-again Israeli-Syrian negotiations, to an extended period of relative calm along the Israeli- Lebanese border. The April understandings would last until Israel’s withdrawal. The recent summer war between Hizbullah and Israel, triggered by the Shia militia’s attack on an Israeli patrol on July 12, masked a number of other factors which would set the stage for the confrontation as well as the Bush administration’s response. Six years of relative quiet had witnessed Israel’s unilateral withdrawal from Lebanon in June of 2000, a steady supply of Katushya rockets—both short and long range—from Iran to Hizbullah, the collapse of Israel’s negotiations with Syria and the Palestinians, and the onset of the worst Israeli-Palestinian war in half a century. A perfect storm was brewing, spawned by the empowerment of both Hizbullah and Hamas, Iranian reach into the Arab-Israeli zone, Syria’s forced withdrawal from Lebanon, a determination by Israel to restore its strategic deterrence in the wake of unilateral withdrawals from Lebanon and Gaza, and an inexperienced Israeli prime minister and defense minister uncertain of how that should be done. -

The Palestinian Economy: a Historical View

The Palestinian Economy: A Historical View Brian J. Friedman, CFA September 30, 2014 Among the thousands of articles written about the Israeli‐Palestinian conflict, very few study the impact of the conflict on the Palestinian economy. According to the CIA approximately 2.2 million Palestinians live in the West Bank (along with 350,000 Jewish settlers) and 1.8 million in the Gaza Strip. Total Gross Domestic Product (GDP) for the Palestinian Authority is $6.6 billion or $1,650 per capita. By way of comparison, Israeli GDP is $273 billion or $35,000 per capita. Israel’s 1.5 million Arab citizens suffer from a significantly lower standard of living than Jewish Israelis. Nonetheless, Israeli Arab GDP per capita is estimated to be $12,000 (Israel Bureau of Statistics). Even without a formal peace agreement, a cessation of Palestinian terrorism and violence could produce a significant peace dividend for the nearly 12 million people living between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea. Unfortunately the Palestinians only started developing a working economy in 2007 with the appointment of Salam Fayyad as Finance Minister, and then again just in the West Bank. While Israel certainly shares some of the blame for the Palestinians economic malaise, economic development was also a low priority for the Palestinian leadership. Until Mahmoud Abbas became President of the Palestinian Authority in 2005, Palestinian factions pursued armed struggle and terrorism against Israel rather than build institutions required for economic prosperity such as banks, courts, capital markets, factories or corporations. The Palestinian Economy Prior to 1967 In June of 1967 the combined militaries of Egypt, Jordan and Syria mobilized against Israel. -

West Bank and Gaza 2020 Human Rights Report

WEST BANK AND GAZA 2020 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Palestinian Authority basic law provides for an elected president and legislative council. There have been no national elections in the West Bank and Gaza since 2006. President Mahmoud Abbas has remained in office despite the expiration of his four-year term in 2009. The Palestinian Legislative Council has not functioned since 2007, and in 2018 the Palestinian Authority dissolved the Constitutional Court. In September 2019 and again in September, President Abbas called for the Palestinian Authority to organize elections for the Palestinian Legislative Council within six months, but elections had not taken place as of the end of the year. The Palestinian Authority head of government is Prime Minister Mohammad Shtayyeh. President Abbas is also chairman of the Palestine Liberation Organization and general commander of the Fatah movement. Six Palestinian Authority security forces agencies operate in parts of the West Bank. Several are under Palestinian Authority Ministry of Interior operational control and follow the prime minister’s guidance. The Palestinian Civil Police have primary responsibility for civil and community policing. The National Security Force conducts gendarmerie-style security operations in circumstances that exceed the capabilities of the civil police. The Military Intelligence Agency handles intelligence and criminal matters involving Palestinian Authority security forces personnel, including accusations of abuse and corruption. The General Intelligence Service is responsible for external intelligence gathering and operations. The Preventive Security Organization is responsible for internal intelligence gathering and investigations related to internal security cases, including political dissent. The Presidential Guard protects facilities and provides dignitary protection. -

Palestine's Occupied Fourth Estate

Arab Media and Society (Issue 17, Winter 2013) Palestine’s Occupied Fourth Estate: An inside look at the work lives of Palestinian print journalists Miriam Berger Abstract While for decades local Palestinian media remained a marginalized and often purely politicized subject, in recent years a series of studies has more critically analyzed the causes and consequences of its seeming diversity but structural underdevelopment.1 However, despite these advances, the specific conditions facing Palestinian journalists in local print media have largely remained underreported. In this study, I address this research gap from a unique perspective: as viewed from the newsroom itself. I present the untold stories of the everyday work life of Palestinian journalists working at the three local Jerusalem- and Ramallah-based newspapers— al-Quds, al-Ayyam, and al-Hayat al-Jadida—from 1994 until January 2012. I discuss the difficult working conditions journalists face within these news organizations, and situate these experiences within the context of Israeli and Palestinian Authority policies and practices that have obstructed the political, economic, and social autonomy of the local press. I first provide a brief background on Palestinian print media, and then I focus on several key areas of concern for the journalists: Israeli and Palestinian violence, the economics of printing in Palestine, the phenomenon of self-censorship, the Palestinian Journalists Syndicate, and internal newspaper organization. This study covers the nearly two decades since the signing of the Oslo Peace Accords between Israel and the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) which put in place the now stalled process of ending the Israeli military occupation of Palestine (used here to refer to the West Bank, East Jerusalem, and Gaza Strip). -

Israeli-Arab Negotiations: Background, Conflicts, and U.S. Policy

Order Code RL33530 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Israeli-Arab Negotiations: Background, Conflicts, and U.S. Policy Updated August 4, 2006 Carol Migdalovitz Specialist in Middle Eastern Affairs Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Israeli-Arab Negotiations: Background, Conflicts, and U.S. Policy Summary After the first Gulf war, in 1991, a new peace process involved bilateral negotiations between Israel and the Palestinians, Jordan, Syria, and Lebanon. On September 13, 1993, Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) signed a Declaration of Principles (DOP), providing for Palestinian empowerment and some territorial control. On October 26, 1994, Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin and King Hussein of Jordan signed a peace treaty. Israel and the Palestinians signed an Interim Self-Rule in the West Bank or Oslo II accord on September 28, 1995, which led to the formation of the Palestinian Authority (PA) to govern the West Bank and Gaza. The Palestinians and Israelis signed additional incremental accords in 1997, 1998, and 1999. Israeli-Syrian negotiations were intermittent and difficult, and were postponed indefinitely in 2000. On May 24, 2000, Israel unilaterally withdrew from south Lebanon after unsuccessful negotiations. From July 11 to 24, 2000, President Clinton held a summit with Israeli and Palestinian leaders at Camp David on final status issues, but they did not produce an accord. A Palestinian uprising or intifadah began that September. On February 6, 2001, Ariel Sharon was elected Prime Minister of Israel, and rejected steps taken at Camp David and afterwards. The post 9/11 war on terrorism prompted renewed U.S. -

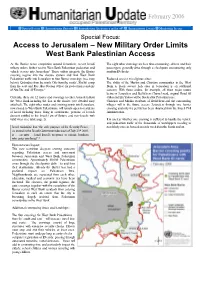

Access to Jerusalem – New Military Order Limits West Bank Palestinian Access

February 2006 Special Focus Humanitarian Reports Humanitarian Assistance in the oPt Humanitarian Events Monitoring Issues Special Focus: Access to Jerusalem – New Military Order Limits West Bank Palestinian Access As the Barrier nears completion around Jerusalem, recent Israeli The eight other crossings are less time-consuming - drivers and their military orders further restrict West Bank Palestinian pedestrian and passengers generally drive through a checkpoint encountering only vehicle access into Jerusalem.1 These orders integrate the Barrier random ID checks. crossing regime into the closure system and limit West Bank Palestinian traffic into Jerusalem to four Barrier crossings (see map Reduced access to religious sites: below): Qalandiya from the north, Gilo from the south2, Shu’fat camp The ability of the Muslim and Christian communities in the West from the east and Ras Abu Sbeitan (Olive) for pedestrian residents Bank to freely access holy sites in Jerusalem is an additional of Abu Dis, and Al ‘Eizariya.3 concern. With these orders, for example, all three major routes between Jerusalem and Bethlehem (Tunnel road, original Road 60 Currently, there are 12 routes and crossings to enter Jerusalem from (Gilo) and Ein Yalow) will be blocked for Palestinian use. the West Bank including the four in the Barrier (see detailed map Christian and Muslim residents of Bethlehem and the surrounding attached). The eight other routes and crossing points into Jerusalem, villages will in the future access Jerusalem through one barrier now closed to West Bank Palestinians, will remain open to residents crossing and only if a permit has been obtained from the Israeli Civil of Israel including those living in settlements, persons of Jewish Administration. -

Armed Conflicts Report - Israel

Armed Conflicts Report - Israel Armed Conflicts Report Israel-Palestine (1948 - first combat deaths) Update: February 2009 Summary Type of Conflict Parties to the Conflict Status of the Fighting Number of Deaths Political Developments Background Arms Sources Economic Factors Summary: 2008 The situation in the Gaza strip escalated throughout 2008 to reflect an increasing humanitarian crisis. The death toll reached approximately 1800 deaths by the end of January 2009, with increased conflict taking place after December 19th. The first six months of 2008 saw increased fighting between Israeli forces and Hamas rebels. A six month ceasefire was agreed upon in June of 2008, and the summer months saw increased factional violence between opposing Palestinian groups Hamas and Fatah. Israel shut down the border crossings between the Gaza strip and Israel and shut off fuel to the power plant mid-January 2008. The fuel was eventually turned on although blackouts occurred sporadically throughout the year. The blockade was opened periodically throughout the year to allow a minimum amount of humanitarian aid to pass through. However, for the majority of the year, the 1.5 million Gaza Strip inhabitants, including those needing medical aid, were trapped with few resources. At the end of January 2009, Israel agreed to the principles of a ceasefire proposal, but it is unknown whether or not both sides can come to agreeable terms and create long lasting peace in 2009. 2007 A November 2006 ceasefire was broken when opposing Palestinian groups Hamas and Fatah renewed fighting in April and May of 2007. In June, Hamas led a coup on the Gaza headquarters of Fatah giving them control of the Gaza Strip. -

Economic Peace in the West Bank and the Fayyad Plan: Are They Working?

The Middle East Institute Policy Brief No. 28 January 2010 Economic Peace in the West Bank and the Fayyad Plan: Are They Working? By Adam Robert Green Prime Minister of the Palestinian Authority Salam Fayyad wants to build the insti- tutional foundations of a Palestinian state by 2011. Improved security in the West Bank, and Israel’s easing of some checkpoints, has boosted the effort by strengthening the West Bank’s economy. This Policy Brief asks whether this muted economic re- vival can be deepened and sustained in the absence of a peace agreement with Israel or a unified Palestinian leadership. For more than 60 years, the Middle East Institute has been dedicated to increasing Americans’ knowledge and understanding of the re- gion. MEI offers programs, media outreach, language courses, scholars, a library, and an academic journal to help achieve its goals. The views expressed in this Policy Brief are those of the author; the Middle East Institute does not take positions on Middle East policy. Economic Peace in the West Bank and the Fayyad Plan: Are They Working? There can be a democratic, de facto Palestinian state by 2011, according to Salam Fayyad, the Prime Minister of the Palestinian Authority (PA). The goal was outlined in an eloquent two-year plan entitled “Ending the Occupation, Establishing the State,”1 published in August 2009, which called for the formation of the institutional founda- tions of statehood prior to, and independent of, an agreement with Israel. The so-called “August plan” is breathlessly ambitious. It envisions the building of a Palestine International Airport in the Jordan Valley, the reconstruction of Gaza Port, and a passage connecting Hamas’ battered province with the West Bank. -

The Fatah-Hamas Reconciliation: Threatening Peace Prospects

The Fatah-Hamas Reconciliation: Threatening Peace Prospects Testimony by David Makovsky Director, Project on the Middle East Peace Process The Washington Institute for Near East Policy February 5, 2013 Hearing of the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Foreign Relations Subcommittee on the Middle East and North Africa Thank you, Madam Chairwoman, Ranking Member Deutch, and distinguished members of the subcommittee for this wonderful opportunity to testify at your very first session of the new Congress. The issue of unity between Fatah and Hamas is something that the two parties have discussed at different levels since 2007 -- and certainly since the two groups announced an agreement in principle in May 2011. Indeed, a meeting between the groups is scheduled in Cairo in the coming days. One should not rule out that such unity will occur; but the past failures of the groups to unite begs various questions and suggests why unity may not occur in the future. While the idea of unity is popular among divided publics everywhere, there have been genuine obstacles to implementing any unity agreement between Fatah and Hamas. First, it seems that neither Fatah -- the mainstream party of the Palestinian Authority (PA) -- nor Hamas wants to risk what it already possesses, namely Hamas's control of Gaza and the PA's control of its part of the West Bank. Each has its own zone and wants to maintain corresponding control. Second, Palestinian president Mahmoud Abbas has not been willing to commit to a Hamas demand for the end of PA security cooperation with Israel in the West Bank, which has resulted in the arrests of Hamas operatives by the PA. -

Critical Policy Brief Number 4/2021

Critical Policy Brief Number 4/2021 The challenges that forced the Fatah movement to postpone the general elections Ala’a Lahlouh and Waleed Ladadweh Strategic Analysis Unit July 2021 Alaa Lahluh: Researcher at the Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research, holds a master’s degree in contemporary Arab studies from Birzeit University, graduated in 2003. He has many research activities in the areas of democratic transformation, accountability and integrity in the security sector and the Palestinian national movement and participated in preparing the Palestine Report on the Arab Security Scale and a report on The State of Reform in the Arab World "The Arab Democracy Barometer" ". Among his publications is "Youth Participation in the Local Authorities Elections 2017", Bethlehem, Student Forum, December 2019, under publication, and “The Problem of Distributing Military Ranks to Workers in the Palestinian Security Forces”, The Civil Forum for Enhancing Good Governance in the Security Sector, November 2019, and “The Migration of Palestinian Christians: Risks and Threats", Ramallah, Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research, 2019, under publication. Walid Ladadweh: Master of Arts in Sociology and Head of the Survey Research Unit at the Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research (Ramallah, Palestine) and a member of the Advisory Council for Palestinian Statistics from 2005-2008. He completed his master’s studies at Birzeit University in Palestine in 2003. He also completed several training courses in the field of research, the last of which was training courses at the University of Michigan in the United States on survey research techniques in 2010. He supervised more than 70 opinion polls in the West Bank and Gaza Strip, and has vast experience in providing proposals, writing reports, preparing, and presenting educational materials, managing field work, and analyzing data using various analysis programs. -

B'tselem and Hamoked Report: One Big Prison

One Big Prison Freedom of Movement to and from the Gaza Strip on the Eve of the Disengagement Plan March 2005 One Big Prison Freedom of Movement to and from the Gaza Strip on the Eve of the Disengagement Plan March 2005 Researched and written by Yehezkel Lein Data coordination by Najib Abu Rokaya, Ariana Baruch, Reem ‘Odeh, Shlomi Swissa Fieldwork by Musa Abu Hashhash, Iyad Haddad, Zaki Kahil, Karim Jubran, Mazen al-Majdalawi, ‘Abd al-Karim S’adi Assistance on legal issues by Yossi Wolfson Translated by Zvi Shulman, Shaul Vardi Edited by Rachel Greenspahn Cover photo: Palestinians wait for relatives at Rafah Crossing (Muhammad Sallem, Reuters) ISSN 0793-520X B’TSELEM - The Israeli Center for Human Rights HaMoked: Center for the Defence of in the Occupied Territories was founded in 1989 by a the Individual, founded by Dr. Lotte group of lawyers, authors, academics, journalists, and Salzberger is an Israeli human rights Knesset members. B’Tselem documents human rights organization founded in 1988 against the abuses in the Occupied Territories and brings them to backdrop of the first intifada. HaMoked is the attention of policymakers and the general public. Its designed to guard the rights of Palestinians, data are based on independent fieldwork and research, residents of the Occupied Territories, official sources, the media, and data from Palestinian whose liberties are violated as a result of and Israeli human rights organizations. Israel's policies. Introduction “The only thing missing in Gaza is a morning Since the beginning of the occupation, line-up,” said Abu Majid, who spent ten Palestinians traveling from the Gaza Strip to years in Israeli prisons, to Israeli journalist Egypt through the Rafah crossing have needed Amira Hass in 1996.1 This sarcastic comment a permit from Israel.