Hutchinson, Yvette (2003) Separating the Substance from the Noise: a Survey of the Black Arts Movement. Phd Thesis, University O

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ishmael Reed Interviewed

Boxing on Paper: Ishmael Reed Interviewed by Don Starnes [email protected] http://www.donstarnes.com/dp/ Don Starnes is an award winning Director and Director of Photography with thirty years of experience shooting in amazing places with fascinating people. He has photographed a dozen features, innumerable documentaries, commercials, web series, TV shows, music and corporate videos. His work has been featured on National Geographic, Discovery Channel, Comedy Central, HBO, MTV, VH1, Speed Channel, Nerdist, and many theatrical and festival screens. Ishmael Reed [in the white shirt] in New Orleans, Louisiana, September 2016 (photo by Tennessee Reed). 284 Africology: The Journal of Pan African Studies, vol.10. no.1, March 2017 Editor’s note: Here author (novelist, essayist, poet, songwriter, editor), social activist, publisher and professor emeritus Ishmael Reed were interviewed by filmmaker Don Starnes during the 2014 University of California at Merced Black Arts Movement conference as part of an ongoing film project documenting powerful leaders of the Black Arts and Black Power Movements. Since 2014, Reed’s interview was expanded to take into account the presidency of Donald Trump. The title of this interview was supplied by this publication. Ishmael Reed (b. 1938) is the winner of the prestigious MacArthur Fellowship (genius award), the renowned L.A. Times Robert Kirsch Lifetime Achievement Award, the Lila Wallace-Reader's Digest Award, a Guggenheim Fellowship, and a Rosenthal Family Foundation Award from the National Institute for Arts and Letters. He has been nominated for a Pulitzer and finalist for two National Book Awards and is Professor Emeritus at the University of California at Berkeley (a thirty-five year presence); he has also taught at Harvard, Yale and Dartmouth. -

The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry Howard Rambsy II The University of Michigan Press • Ann Arbor First paperback edition 2013 Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2011 All rights reserved Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid-free paper 2016 2015 2014 2013 5432 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rambsy, Howard. The black arts enterprise and the production of African American poetry / Howard Rambsy, II. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-472-11733-8 (cloth : acid-free paper) 1. American poetry—African American authors—History and criticism. 2. Poetry—Publishing—United States—History—20th century. 3. African Americans—Intellectual life—20th century. 4. African Americans in literature. I. Title. PS310.N4R35 2011 811'.509896073—dc22 2010043190 ISBN 978-0-472-03568-7 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-472-12005-5 (e-book) Cover illustrations: photos of writers (1) Haki Madhubuti and (2) Askia M. Touré, Mari Evans, and Kalamu ya Salaam by Eugene B. Redmond; other images from Shutterstock.com: jazz player by Ian Tragen; African mask by Michael Wesemann; fist by Brad Collett. -

A Collection Analysis of the African-American Poetry Holdings in the De Grummond Collection Sarah J

SLIS Connecting Volume 2 | Issue 1 Article 9 2013 A Collection Analysis of the African-American Poetry Holdings in the de Grummond Collection Sarah J. Heidelberg Follow this and additional works at: http://aquila.usm.edu/slisconnecting Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Heidelberg, Sarah J. (2013) "A Collection Analysis of the African-American Poetry Holdings in the de Grummond Collection," SLIS Connecting: Vol. 2: Iss. 1, Article 9. DOI: 10.18785/slis.0201.09 Available at: http://aquila.usm.edu/slisconnecting/vol2/iss1/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in SLIS Connecting by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Collection Analysis of the African‐American Poetry Holdings in the de Grummond Collection By Sarah J. Heidelberg Master’s Research Project, November 2010 Performance poetry is part of the new black poetry. Readers: Dr. M.J. Norton This includes spoken word and slam. It has been said Dr. Teresa S. Welsh that the introduction of slam poetry to children can “salvage” an almost broken “relationship with poetry” (Boudreau, 2009, 1). This is because slam Introduction poetry makes a poets’ art more palatable for the Poetry is beneficial for both children and adults; senses and draws people to poetry (Jones, 2003, 17). however, many believe it offers more benefit to Even if the poetry that is spoken at these slams is children (Vardell, 2006, 36). The reading of poetry sometimes not as developed or polished as it would correlates with literacy attainment (Maynard, 2005; be hoped (Jones, 2003, 23). -

Broadside Read- a Brief Chronology of Major Events in Trous Failure

NEWSLETTER OF THE THEATRE LIBRARY ASSOCIATION Volume 17, Number 1/Volume 17, Number 2 SPECIAL DOUBLE ISSUE Summer/Fa111989 EXHIBITION SURVEYS MANHATTAN'S EARLY THEATRE HISTORY L An exhibition spotlighting three early New York theatres was on view in the Main I Gallery of The New York Public Library at Lincoln Center from February 13, 1990 through March 31, 1990. Focusing on the Park Theatre on Park Row, Niblo's Garden on Broadway and Prince Street, and Wal- lack's, later called the Star, on Broadway and 13th Street, the exhibition attempted to show, through the use of maps, photo- graphic blowups, programs and posters, the richness of the developing New York theatre scene as it moved northward from lower Manhattan. The Park Theatre has been called "the first important theatre in the United States." It opened on January 29, 1798, across from the Commons (the Commons is now City Hall Park-City Hall was built in 1811). The opening production, As You Like It, was presented with some of the fin- est scenery ever seen. The theatre itself, which could accommodate almost 2,000, was most favorably reviewed. It was one of the most substantial buildings erected in the city to that date- the size of the stage was a source of amazement to both cast and audience. In the early nineteenth century, to increase ticket sales, manager Stephen Price introduced the "star sys- tem" (the importation of famous English stars). This kept attendance high but to some extent discouraged the growth of in- digenous talent. In its later days the Park was home to a fine company, which, in addition to performing the classics, pre- sented the work of the emerging American playwrights. -

Guide to African American History Materials in Manuscript and Visual Collections at the Indiana Historical Society

Guide to African American History Materials in Manuscript and Visual Collections at the Indiana Historical Society Originally compiled as a printed guide (Selected African-American History Collections) by Wilma L. Gibbs, 1996 Revised and updated by Wilma L. Gibbs as an online guide, 2002 and 2004 Introduction Personal Papers Organizations, Institutions, and Projects Communities Education Race Relations Religious Institutions 15 July 2004 Manuscript and Visual Collections Department William Henry Smith Memorial Library Indiana Historical Society 450 West Ohio Street Indianapolis, IN 46202-3269 www.indianahistory.org Introduction This guide describes manuscript and visual collections in the William Henry Smith Memorial Library of the Indiana Historical Society (IHS) that document the experiences of African Americans in Indiana. In 1982, a collecting effort was formalized at the Historical Society to address the concern for the paucity of records available for doing research on the history of African Americans in the state. The purpose of that effort continues to be to collect, process, preserve, and disseminate information related to the history of black Hoosiers. The Archivist, African American History is available to answer and direct research questions from the public. Indiana Historical Society members can receive Black History News & Notes, a quarterly newsletter that publicizes library collections, relevant historical events, and short papers pertaining to Indiana’s black history. Preserving Indiana’s African American heritage is a cooperative venture. The Society needs your help in providing information about existing records in attics, basements, and garages that can be added to the library’s collections. As more records are collected and organized, a more accurate and complete interpretation of Indiana history will emerge. -

Here May Is Not Rap Be Music D in Almost Every Major Language,Excerpted Including Pages Mandarin

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF THE BLACK ARTS MOVEMENT ed or printed. Edited by istribut Verner D. Mitchell Cynthia Davis an uncorrected page proof and may not be d Excerpted pages for advance review purposes only. All rights reserved. This is ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD Lanham • Boulder • New York • London 18_985_Mitchell.indb 3 2/25/19 2:34 PM ed or printed. Published by Rowman & Littlefield An imprint of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 istribut www.rowman.com 6 Tinworth Street, London, SE11 5AL, United Kingdom Copyright © 2019 by The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Mitchell, Verner D., 1957– author. | Davis, Cynthia, 1946– author. Title: Encyclopedia of the Black Arts Movement / Verner D. Mitchell, Cynthia Davis. Description: Lanhaman : uncorrectedRowman & Littlefield, page proof [2019] and | Includes may not bibliographical be d references and index. Identifiers:Excerpted LCCN 2018053986pages for advance(print) | LCCN review 2018058007 purposes (ebook) only. | AllISBN rights reserved. 9781538101469This is (electronic) | ISBN 9781538101452 | ISBN 9781538101452 (cloth : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Black Arts movement—Encyclopedias. Classification: LCC NX512.3.A35 (ebook) | LCC NX512.3.A35 M58 2019 (print) | DDC 700.89/96073—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018053986 The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992. -

African-American Writers

AFRICAN-AMERICAN WRITERS Philip Bader Note on Photos Many of the illustrations and photographs used in this book are old, historical images. The quality of the prints is not always up to current standards, as in some cases the originals are from old or poor-quality negatives or are damaged. The content of the illustrations, however, made their inclusion important despite problems in reproduction. African-American Writers Copyright © 2004 by Philip Bader All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. For information contact: Facts On File, Inc. 132 West 31st Street New York NY 10001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bader, Philip, 1969– African-American writers / Philip Bader. p. cm.—(A to Z of African Americans) Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and indexes. ISBN 0-8160-4860-6 (acid-free paper) 1. American literature—African American authors—Bio-bibliography—Dictionaries. 2. African American authors—Biography—Dictionaries. 3. African Americans in literature—Dictionaries. 4. Authors, American—Biography—Dictionaries. I. Title. II. Series. PS153.N5B214 2004 810.9’96073’003—dc21 2003008699 Facts On File books are available at special discounts when purchased in bulk quantities for businesses, associations, institutions, or sales promotions. Please call our Special Sales Department in New York at (212) 967-8800 or (800) 322-8755. You can find Facts On File on the World Wide Web at http://www.factsonfile.com Text design by Joan M. -

Black Theatre Movement PREPRINT

PREPRINT - Olga Barrios, The Black Theatre Movement in the United States and in South Africa . Valencia: Universitat de València, 2008. 2008 1 To all African people and African descendants and their cultures for having brought enlightenment and inspiration into my life 3 CONTENTS Pág. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS …………………………………………………………… 6 INTRODUCTION …………………………………………………………………….. 9 CHAPTER I From the 1950s through the 1980s: A Socio-Political and Historical Account of the United States/South Africa and the Black Theatre Movement…………………. 15 CHAPTER II The Black Theatre Movement: Aesthetics of Self-Affirmation ………………………. 47 CHAPTER III The Black Theatre Movement in the United States. Black Aesthetics: Amiri Baraka, Ed Bullins, and Douglas Turner Ward ………………………………. 73 CHAPTER IV The Black Theatre Movement in the United States. Black Women’s Aesthetics: Lorraine Hansberry, Adrienne Kennedy, and Ntozake Shange …………………….. 109 CHAPTER V The Black Theatre Movement in South Africa. Black Consciousness Aesthetics: Matsemala Manaka, Maishe Maponya, Percy Mtwa, Mbongeni Ngema and Barney Simon …………………………………... 144 CHAPTER VI The Black Theatre Movement in South Africa. Black South African Women’s Voices: Fatima Dike, Gcina Mhlophe and Other Voices ………………………………………. 173 CONCLUSION ………………………………………………………………………… 193 BIBLIOGRAPHY ……………………………………………………………………… 199 APPENDIX I …………………………………………………………………………… 221 APPENDIX II ………………………………………………………………………….. 225 5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Writing this book has been an immeasurable reward, in spite of the hard and critical moments found throughout its completion. The process of this culmination commenced in 1984 when I arrived in the United States to pursue a Masters Degree in African American Studies for which I wish to thank very sincerely the Fulbright Fellowships Committee. I wish to acknowledge the Phi Beta Kappa Award Selection Committee, whose contribution greatly helped solve my financial adversity in the completion of my work. -

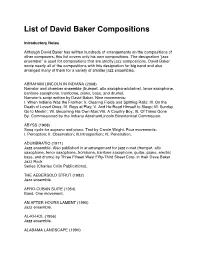

List of David Baker Compositions

List of David Baker Compositions Introductory Notes Although David Baker has written hundreds of arrangements on the compositions of other composers, this list covers only his own compositions. The designation “jazz ensemble” is used for compositions that are strictly jazz compositions. David Baker wrote nearly all of the compositions with this designation for big band and also arranged many of them for a variety of smaller jazz ensembles. ABRAHAM LINCOLN IN INDIANA (2008) Narrator and chamber ensemble (trumpet, alto saxophone/clarinet, tenor saxophone, baritone saxophone, trombone, piano, bass, and drums). Narratorʼs script written by David Baker. Nine movements: I. When Indiana Was the Frontier; II. Clearing Fields and Splitting Rails; III. On the Death of Loved Ones; IV. Boys at Play; V. And He Read Himself to Sleep; VI. Sunday Go to Meetinʼ; VII. Becoming His Own Man;VIII. A Country Boy; IX. Of Times Gone By. Commissioned by the Indiana AbrahamLincoln Bicentennial Commission. ABYSS (1968) Song cycle for soprano and piano. Text by Carole Wright. Four movements: I. Perception; II. Observation; III.Introspection; IV. Penetration. ADUMBRATIO (1971) Jazz ensemble. Also published in anarrangement for jazz nonet (trumpet, alto saxophone, tenor saxophone, trombone, baritone saxophone, guitar, piano, electric bass, and drums) by Three Fifteen West Fifty-Third Street Corp. in their Dave Baker Jazz Rock Series (Charles Colin Publications). THE AEBERSOLD STRUT (1982) Jazz ensemble. AFRO-CUBAN SUITE (1954) Band. One movement. AN AFTER HOURS LAMENT (1990) Jazz ensemble. AL-KI-HOL (1956) Jazz ensemble. ALABAMA LANDSCAPE (1990) Bass-baritone and orchestra. Text by Mari Evans. Commissioned by William Brown. -

African-American Poets Past and Present: a Historical View

Curriculum Units by Fellows of the Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute 1991 Volume IV: Recent American Poetry: Expanding the Canon African-American Poets Past and Present: A Historical View Curriculum Unit 91.04.04 by Joyce Patton African American Poets Past and Present: A historical View will address in this unit African-American poets and the poetry they wrote throughout the course of history. They will be listed in chronological order as they appear in history. The Eighteenth Century Beginnings (1700-1800) brought us Phillis Wheatley and Jupiter Hammon. The Struggle Against Slavery and Racism (1800-1860) brought us George Moses Horton and Frances W. Harper. The Black Man in the Civil War (1861-1865). There were not any poets that came to us in this time frame. Reconstruction and Reaction (1865-1915) brought us Paul Laurence Dunbar, W.E.B. Du Bois, William S. Braithwaite, and Fenton Johnson. Renaissance and Radicalism (1915-1945) brought us James Weldon Johnson, Claude McKay, Langston Hughes, Contee Cullen, Angelina Grimke, Arna Bontemps, and Sterling Brown. The Present Generation brought us Robert Hayden, Gwendolyn Brooks, Imamu Baraka (LeRoi Jones), Owen Dodson, Samuel Allen, Mari E. Evans, Etheridge Knight, Don L. Lee, Sonia Sanchez and Nikki Giovanni. These poets have written poems that express the feelings of African-Americans from slavery to the present. Poems were not only things written during these times. There was folk literature, prison songs, spirituals, the blues, work songs, pop chart music, and rap music the craze of today, plus sermons delivered by ministers. The objectives of this unit are to teach children about the poets, the poems written expressing their feelings, and how to write poetry. -

And Practices at Historically Black Colleges and Universities

A^ü. i REPRESENTATIVE DIRECTORS, BLACK THEATRE PRODUCTIONS, AND PRACTICES AT HISTORICALLY BLACK COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES 1968-1978 Alex C. Marshall A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY March 1980 Approved by Doctoral Committee: Graduate College„Representative il ABSTRACT This investigation described the status of Black Theatre productions and practices at four year historically Black Colleges and Universities with degree programs in Speech and Drama, Speech and Theatre, or Communi cations. The objectives of this study were: (1) to profile the directors and their production philosophies and practices; (2) to chronicle and categorize Black plays produced during 1968-1978; (3) to characterize the practices in theatre management and (4) to describe trends, and chart some implications from the data collected. Primary data for this study was obtained from mailed questionnaires and thirty-two audio recorded interviews with theatre practitioners at the 43rd National Association of Dramatic and Speech Arts (NADSA) Convention in Chicago, Illinois, on April 4-7, 1979. Thirty-six questionnaires were mailed and thirty (83%) were returned; twenty-four (66%) were usable for this investigation. Results of the study revealed that the directors were academically trained, experienced, of varying ages, Black, male dominated, and dedicated The absence of women as theatre directors suggested areas for study to clarify the reasons for this situation. Respondents believed that productions should be primarily enter taining which suggested their having traditional responses to the function of art that has been assailed by the proponents of the Black Arts Movement who call for art as a political influence. -

Section 1049 / Spring 2015 African-American Theatre History and Practice Class Meeting Time - MWF Per

Af. Am. Theatre History - Spring 2015/ Page 1 University of Florida - College of the Arts - School of Theatre and Dance THE 3231: Section 1049 / Spring 2015 African-American Theatre History and Practice Class Meeting Time - MWF Per. 7 (1:55-2:45) / MCCB G086 Dr. Mikell Pinkney / Office: 222 McGuire Pavilion / 273-0512 / [email protected] Office Hours: Tues. 2:00-4:00PM & Thurs. 9:30-10:20AM; also by appointment Thurs. 2-4PM Course Content: An investigation and examination of the historical origins and development of theatre by, for and about black/ African-Americans from the late 18th Century through the end of the 20th Century and beyond. The course examines theatre from an historical, philosophical, ethnic and racial perspective and provides a theoretical understanding of cultural studies and sociological influences on and within a larger American society as represented by theatre created for, about, by and through the perspectives of African- Americans, highlighting a systematic move form cultural margin to mainstream theatrical practices and acknowledgements. Objectives and Outcomes: Students will learn the historical contexts of playwrights, performers, theorists & theoretical concepts, productions and organizations that help to identify African-American Theatre as an indigenous American institution. Terminology and concepts of cultural studies are learned as a means for access and critical thinking about the subject. Discussions are developed through readings, lectures, videos, and analysis of dramatic literature of the field. Two tests, a mid-term exam, a group presentation and a final paper are required to access competence, communication and critical thinking skills. Student Learning Objectives: 1. Students identify and analyze key elements, biases and influences that shape thought within the discipline (Critical Thinking) 2.