Foundations of Black Women's Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry Howard Rambsy II The University of Michigan Press • Ann Arbor First paperback edition 2013 Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2011 All rights reserved Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid-free paper 2016 2015 2014 2013 5432 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rambsy, Howard. The black arts enterprise and the production of African American poetry / Howard Rambsy, II. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-472-11733-8 (cloth : acid-free paper) 1. American poetry—African American authors—History and criticism. 2. Poetry—Publishing—United States—History—20th century. 3. African Americans—Intellectual life—20th century. 4. African Americans in literature. I. Title. PS310.N4R35 2011 811'.509896073—dc22 2010043190 ISBN 978-0-472-03568-7 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-472-12005-5 (e-book) Cover illustrations: photos of writers (1) Haki Madhubuti and (2) Askia M. Touré, Mari Evans, and Kalamu ya Salaam by Eugene B. Redmond; other images from Shutterstock.com: jazz player by Ian Tragen; African mask by Michael Wesemann; fist by Brad Collett. -

A Collection Analysis of the African-American Poetry Holdings in the De Grummond Collection Sarah J

SLIS Connecting Volume 2 | Issue 1 Article 9 2013 A Collection Analysis of the African-American Poetry Holdings in the de Grummond Collection Sarah J. Heidelberg Follow this and additional works at: http://aquila.usm.edu/slisconnecting Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Heidelberg, Sarah J. (2013) "A Collection Analysis of the African-American Poetry Holdings in the de Grummond Collection," SLIS Connecting: Vol. 2: Iss. 1, Article 9. DOI: 10.18785/slis.0201.09 Available at: http://aquila.usm.edu/slisconnecting/vol2/iss1/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in SLIS Connecting by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Collection Analysis of the African‐American Poetry Holdings in the de Grummond Collection By Sarah J. Heidelberg Master’s Research Project, November 2010 Performance poetry is part of the new black poetry. Readers: Dr. M.J. Norton This includes spoken word and slam. It has been said Dr. Teresa S. Welsh that the introduction of slam poetry to children can “salvage” an almost broken “relationship with poetry” (Boudreau, 2009, 1). This is because slam Introduction poetry makes a poets’ art more palatable for the Poetry is beneficial for both children and adults; senses and draws people to poetry (Jones, 2003, 17). however, many believe it offers more benefit to Even if the poetry that is spoken at these slams is children (Vardell, 2006, 36). The reading of poetry sometimes not as developed or polished as it would correlates with literacy attainment (Maynard, 2005; be hoped (Jones, 2003, 23). -

Guide to African American History Materials in Manuscript and Visual Collections at the Indiana Historical Society

Guide to African American History Materials in Manuscript and Visual Collections at the Indiana Historical Society Originally compiled as a printed guide (Selected African-American History Collections) by Wilma L. Gibbs, 1996 Revised and updated by Wilma L. Gibbs as an online guide, 2002 and 2004 Introduction Personal Papers Organizations, Institutions, and Projects Communities Education Race Relations Religious Institutions 15 July 2004 Manuscript and Visual Collections Department William Henry Smith Memorial Library Indiana Historical Society 450 West Ohio Street Indianapolis, IN 46202-3269 www.indianahistory.org Introduction This guide describes manuscript and visual collections in the William Henry Smith Memorial Library of the Indiana Historical Society (IHS) that document the experiences of African Americans in Indiana. In 1982, a collecting effort was formalized at the Historical Society to address the concern for the paucity of records available for doing research on the history of African Americans in the state. The purpose of that effort continues to be to collect, process, preserve, and disseminate information related to the history of black Hoosiers. The Archivist, African American History is available to answer and direct research questions from the public. Indiana Historical Society members can receive Black History News & Notes, a quarterly newsletter that publicizes library collections, relevant historical events, and short papers pertaining to Indiana’s black history. Preserving Indiana’s African American heritage is a cooperative venture. The Society needs your help in providing information about existing records in attics, basements, and garages that can be added to the library’s collections. As more records are collected and organized, a more accurate and complete interpretation of Indiana history will emerge. -

Here May Is Not Rap Be Music D in Almost Every Major Language,Excerpted Including Pages Mandarin

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF THE BLACK ARTS MOVEMENT ed or printed. Edited by istribut Verner D. Mitchell Cynthia Davis an uncorrected page proof and may not be d Excerpted pages for advance review purposes only. All rights reserved. This is ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD Lanham • Boulder • New York • London 18_985_Mitchell.indb 3 2/25/19 2:34 PM ed or printed. Published by Rowman & Littlefield An imprint of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 istribut www.rowman.com 6 Tinworth Street, London, SE11 5AL, United Kingdom Copyright © 2019 by The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Mitchell, Verner D., 1957– author. | Davis, Cynthia, 1946– author. Title: Encyclopedia of the Black Arts Movement / Verner D. Mitchell, Cynthia Davis. Description: Lanhaman : uncorrectedRowman & Littlefield, page proof [2019] and | Includes may not bibliographical be d references and index. Identifiers:Excerpted LCCN 2018053986pages for advance(print) | LCCN review 2018058007 purposes (ebook) only. | AllISBN rights reserved. 9781538101469This is (electronic) | ISBN 9781538101452 | ISBN 9781538101452 (cloth : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Black Arts movement—Encyclopedias. Classification: LCC NX512.3.A35 (ebook) | LCC NX512.3.A35 M58 2019 (print) | DDC 700.89/96073—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018053986 The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992. -

African-American Writers

AFRICAN-AMERICAN WRITERS Philip Bader Note on Photos Many of the illustrations and photographs used in this book are old, historical images. The quality of the prints is not always up to current standards, as in some cases the originals are from old or poor-quality negatives or are damaged. The content of the illustrations, however, made their inclusion important despite problems in reproduction. African-American Writers Copyright © 2004 by Philip Bader All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. For information contact: Facts On File, Inc. 132 West 31st Street New York NY 10001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bader, Philip, 1969– African-American writers / Philip Bader. p. cm.—(A to Z of African Americans) Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and indexes. ISBN 0-8160-4860-6 (acid-free paper) 1. American literature—African American authors—Bio-bibliography—Dictionaries. 2. African American authors—Biography—Dictionaries. 3. African Americans in literature—Dictionaries. 4. Authors, American—Biography—Dictionaries. I. Title. II. Series. PS153.N5B214 2004 810.9’96073’003—dc21 2003008699 Facts On File books are available at special discounts when purchased in bulk quantities for businesses, associations, institutions, or sales promotions. Please call our Special Sales Department in New York at (212) 967-8800 or (800) 322-8755. You can find Facts On File on the World Wide Web at http://www.factsonfile.com Text design by Joan M. -

List of David Baker Compositions

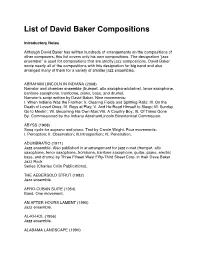

List of David Baker Compositions Introductory Notes Although David Baker has written hundreds of arrangements on the compositions of other composers, this list covers only his own compositions. The designation “jazz ensemble” is used for compositions that are strictly jazz compositions. David Baker wrote nearly all of the compositions with this designation for big band and also arranged many of them for a variety of smaller jazz ensembles. ABRAHAM LINCOLN IN INDIANA (2008) Narrator and chamber ensemble (trumpet, alto saxophone/clarinet, tenor saxophone, baritone saxophone, trombone, piano, bass, and drums). Narratorʼs script written by David Baker. Nine movements: I. When Indiana Was the Frontier; II. Clearing Fields and Splitting Rails; III. On the Death of Loved Ones; IV. Boys at Play; V. And He Read Himself to Sleep; VI. Sunday Go to Meetinʼ; VII. Becoming His Own Man;VIII. A Country Boy; IX. Of Times Gone By. Commissioned by the Indiana AbrahamLincoln Bicentennial Commission. ABYSS (1968) Song cycle for soprano and piano. Text by Carole Wright. Four movements: I. Perception; II. Observation; III.Introspection; IV. Penetration. ADUMBRATIO (1971) Jazz ensemble. Also published in anarrangement for jazz nonet (trumpet, alto saxophone, tenor saxophone, trombone, baritone saxophone, guitar, piano, electric bass, and drums) by Three Fifteen West Fifty-Third Street Corp. in their Dave Baker Jazz Rock Series (Charles Colin Publications). THE AEBERSOLD STRUT (1982) Jazz ensemble. AFRO-CUBAN SUITE (1954) Band. One movement. AN AFTER HOURS LAMENT (1990) Jazz ensemble. AL-KI-HOL (1956) Jazz ensemble. ALABAMA LANDSCAPE (1990) Bass-baritone and orchestra. Text by Mari Evans. Commissioned by William Brown. -

African-American Poets Past and Present: a Historical View

Curriculum Units by Fellows of the Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute 1991 Volume IV: Recent American Poetry: Expanding the Canon African-American Poets Past and Present: A Historical View Curriculum Unit 91.04.04 by Joyce Patton African American Poets Past and Present: A historical View will address in this unit African-American poets and the poetry they wrote throughout the course of history. They will be listed in chronological order as they appear in history. The Eighteenth Century Beginnings (1700-1800) brought us Phillis Wheatley and Jupiter Hammon. The Struggle Against Slavery and Racism (1800-1860) brought us George Moses Horton and Frances W. Harper. The Black Man in the Civil War (1861-1865). There were not any poets that came to us in this time frame. Reconstruction and Reaction (1865-1915) brought us Paul Laurence Dunbar, W.E.B. Du Bois, William S. Braithwaite, and Fenton Johnson. Renaissance and Radicalism (1915-1945) brought us James Weldon Johnson, Claude McKay, Langston Hughes, Contee Cullen, Angelina Grimke, Arna Bontemps, and Sterling Brown. The Present Generation brought us Robert Hayden, Gwendolyn Brooks, Imamu Baraka (LeRoi Jones), Owen Dodson, Samuel Allen, Mari E. Evans, Etheridge Knight, Don L. Lee, Sonia Sanchez and Nikki Giovanni. These poets have written poems that express the feelings of African-Americans from slavery to the present. Poems were not only things written during these times. There was folk literature, prison songs, spirituals, the blues, work songs, pop chart music, and rap music the craze of today, plus sermons delivered by ministers. The objectives of this unit are to teach children about the poets, the poems written expressing their feelings, and how to write poetry. -

Etheridge Knight Festival Collection, 1957-2012

Collection #s M 1072 OM 0532 DVD 317-330 ETHERIDGE KNIGHT FESTIVAL COLLECTION, 1957-2012 Collection Information Sketch Scope and Content Note Series Contents Cataloging Information Processed by Nicole Poletika October 2013 Manuscript and Visual Collections Department William Henry Smith Memorial Library Indiana Historical Society 450 West Ohio Street Indianapolis, IN 46202-3269 www.indianahistory.org COLLECTION INFORMATION VOLUME OF 2 manuscript boxes, 8 OM folders, 3 color photograph folders, COLLECTION: 3 OM photograph folders, 1 DVD box COLLECTION 1957-2012 DATES: PROVENANCE: Eunice Knight-Bowens RESTRICTIONS: None COPYRIGHT: REPRODUCTION Permission to reproduce or publish material in this collection RIGHTS: must be obtained from the Indiana Historical Society. ALTERNATE FORMATS: RELATED Etheridge Knight Jr. Papers (M 0798) HOLDINGS: ACCESSION 2008.0285, 2011.0240, 2012.0146 NUMBER: NOTES: HISTORICAL SKETCH The Etheridge Knight Festival of the Arts was started in 1992 by Eunice Knight-Bowens and her family as a tribute to her brother’s legacy and the arts community. A youth poetry component was added in 1994. The Festival began as an annual celebration bringing together local and national individuals who perform for the community and serve as mentors to help develop emerging artists. It stressed making arts available more broadly to all groups within the community. On April 19, 2012, the Festival hosted the “Evening with the Legends” honoring nationally renowned legends Amiri Baraka, Mari Evans, Haki Madhubuti, and Sonia Sanchez. The event, held at the Indiana Landmarks Center paid homage to the life of Gwendolyn Brooks (1917–2000). Biographical Sketch of Etheridge Knight, Jr. Etheridge Knight, Jr. (son of Etheridge, Sr. -

A Historical Guide to Langston Hughes

A Historical Guide to Langston Hughes STEVEN C. TRACY, Editor OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS Langston Hughes The Historical Guides to American Authors is an interdisciplinary, historically sensitive series that combines close attention to the United States’ most widely read and studied authors with a strong sense of time, place, and history. Placing each writer in the context of the vi- brant relationship between literature and society, volumes in this series contain historical essays written on subjects of contemporary social, political, and cultural relevance. Each volume also includes a capsule biography and illustrated chronology detailing important cultural events as they coincided with the author’s life and works, while pho- tographs and illustrations dating from the period capture the flavor of the author’s time and social milieu. Equally accessible to students of literature and of life, the volumes offer a complete and rounded picture of each author in his or her America. A Historical Guide to Ernest Hemingway Edited by Linda Wagner-Martin A Historical Guide to Walt Whitman Edited by David S. Reynolds A Historical Guide to Ralph Waldo Emerson Edited by Joel Myerson A Historical Guide to Nathaniel Hawthorne Edited by Larry Reynolds A Historical Guide to Edgar Allan Poe Edited by J. Gerald Kennedy A Historical Guide to Henry David Thoreau Edited by William E. Cain A Historical Guide to Mark Twain Edited by Shelley Fisher Fishkin A Historical Guide to Edith Wharton Edited by Carol J. Singley A Historical Guide to Langston Hughes Edited by Steven C. Tracy A Historical Guide to Langston Hughes f . 1 3 Oxford New York Auckland Bangkok Buenos Aires Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kolkata Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi São Paulo Shanghai Taipei Tokyo Toronto Copyright © by Oxford University Press, Inc. -

Hutchinson, Yvette (2003) Separating the Substance from the Noise: a Survey of the Black Arts Movement. Phd Thesis, University O

"Separating the Substance from the Noise": A Survey of the Black Arts Movement. by Yvette Hutchinson. Thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, October 2002 Contents Abstract Acknowledgements Dedication Introduction Chapter One: The Development of the Black Aesthetic Chapter Two: Representation of a Black Hero : William Styron's Nat Turner and a Black Critical Response Chapter Three: Black Aesthetic Critics and Criticism. Chapter Four: Critical Approaches to Blackness and the New Black Poetry Chapter Five: Building Black Institutions: The Development of Black Theatre Chapter Six: "When State Magicians Fail, Unofficial Magicians Become Stronger"Dissent and Aesthetic Variations Chapter Seven: The Second Stage: Revolution and "Womanist" Essentialism in Black Women's Poetry and Fiction Conclusion: "Relanguaging" Black People in a Black Consciousness. Bibliography: Works Cited Works Consulted Abstract This thesis will survey the Black Arts Movement in America from the early 1960s to the 1970s. The Movement was characterised by a proliferation of poetry, exhibitions and plays. Rather than close textual analyses, the thesis will take a panoramic view of the Movement considering the movement's two main aims: the development of a canon of work and the establishment of black institutions. The main critical arguments occasioned by these literary developments contributed to the debate on the establishment of a Black Aesthetic through an essentialist approach to the creation and assessmentof black art works. This survey considers the motivations behind the artists' essentialism, recognising their aim to challenge white criticism of black forms of cultural expression. Underpinning the Movement's critical discourse was the theme of blackness, a philosophy of racial consciousnessthat blended a rather crude biological determinism with the ideology of a unique black experience. -

Ed 064 724 Author Title Institut/On Pub Date Note

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 064 724 CB 200 015 AUTHOR Randolph, Gloria D. TITLE Variations on Black Themes:English, Black Literature. INSTITUT/ON Dade County Public Schools,Miami, Fla. PUB DATE 71 NOTE 45p. EDRS PRICE MF-60.65 HC -$3.29 DESCRIPTORS American Literature; Course Content; *Curriculum Guides; *English Curriculum; Literature; *Negro Literature IDENTIFIERS *Quinmester Program ABSTRACT Variations on Black Themes, an introductory coursein the study of black literature, permits students tomake cursory examination of representative works of many blackwriters for the purpose of identifying majorwriters and recurring themes. The course content includes: introduction to some worksof major Black American authors; identification of lesser known writers;identification of recurring themes, such as non the beauty ofblacknessn, nlove is a sometimes thing", nto be freen, nas we lay dyingn,and nthe black womann; and finally, comparison ofvarious writers' attitudes toward the identified themes. An 8-page listing of resourcematerials is included. (CL) eat r 1%. 0 AUTHORIZEDCOUltilOF INSTRUCTION FOR THE 0 0 LANGUWE ANS ° Variations on Black Thanes s 5111.11 C.) 5112.11 5113.11 5114.11 5115.11 5116.11 DIVISION OF INSTRUCTION1971 tap st, US.ppAwnnwrcosseaus. aDvanum IWILIAM! OPPICI OP IOWIATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS SUN REPRO. NCO EXACTLY As RECEIVED PM NI PERSON OR ORGANISATION ORIG. INATING IT POINTS OP VIEW ON OPIN. IONS STATED 00 NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OPPICIAL OFFICE OP IOU. CATION POSITION OR POLICY. VARIATIONS ON BLACK MUSS 5111.11 5112.11 5113.11 5114.11 5115.11 5116.11 English, Black Literature Written by Gloria D. Randolph for the DIVISION OF INSTRUCTION Dade °aunty Public Schools Miami, Florida 1971 2 "PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE THIS COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL HAS BEEN GRANTED By Dade County Public Scboola TO ERIC AND ORGANIZATIONS OPERATING UNDER AGREEMENTS WITH THE U.S. -

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, October 1974)

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 104 990 UD 014 978 AUTHOR Browne, Juanita M. TITLE The Black Woman. PUB DATE Oct 74 NOTE 21p.; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Association for the Study of Afro-American Life and History (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, October 1974) EDRS PRICE MR-$0.76 HC-$1.58 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS African American Studies; African History; *Females; Feminism; *Negro History; *Negro Mothers; Negro Role; *Racial Discrimination; Role Theory; Sex Discrimination; *Sex Role; Sex Stereotypes; Slavery; United States History; Working Women ABSTRACT The Black woman has been the transmitter of culture in the black community. Two of the important roles of African women were perpetuated during slavery and continue until today.They are her role in economic endeavor and her close bond with her children. The woman in African society was additionally politically significant.. The black woman has been defined as a double nonperson. American women have been denied their history. History in the past has been written by white male historians and has been a story of mankind, utilizing learned spokesmen from a male point of view. Black history has been written by black historians. Their spokesmen have been chosen by a racist society. This study shows that the life of the black woman under slavery was in every respect more difficult and even more cruel than that of the men. Black women were,though it is little known, active in the revolution and resisted both violently and nonviolently. The matriarch myth is discussed in this study as well as the role of the black woman and women's liberation.