The 'Flip-Flop' Approach to Terrorism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alevi Lamtivy

tar¡ h\/y vakfi Zindankapı, Değirmen Sokak, N o:15, 34134 Eminönü/İstanbul Tel: (0212) 522 02 02 - Faks: (0212) 513 54 00 wwTV.tarihvakfi.org.tr - yayin® tarihvakfi.org.tr Özgün Adı Alevi lAmtivy © Tarih Vakfı Yvırt Yayınları Bu çeviri, İstanbul İsveç Araştırma Enstitüsü ile yapılan anlaşma çerçevesinde yayımlanmıştır. JS^ I'ÎL ®L1 ki^ba katkılarından dolayı § g İstanbul İsveç Araştırma Enstitüsü’ııe %, P teşekkür ederiz. 'r ° 'V / N ^ 0 Kapak Resmi “İmam Ali”, cam boyama, Ömer Bortaçina Koleksiyonu, Cam Altmda-Yir Bin Fersah, Yapı Kredi Kültür Sanat Yayıncılık, İstanbul, 1998. Yayıma Hazırlayan Tansel Demirci Ali Berktav Kitap Tasarımı Halıık Tunçay Kitap Uygulama Tarkan l ogo Kapak Uygulama Harun Yılmaz (MYRA) Baskı Yenigiiven Matbaacılık San. Tic. Ltd. Şti. Tel: (0212) 567 69 20 Birinci Basım: Mart 1999 İkinci Basım: Haziran 2003 Üçüncü Basım: Eylül 2010 ISBN 978-975-333-093-0 ALEVİ KİMLİĞİ EDİTÖRLER T. OLSSON, E. ÖZDALGA, C. RAUDVERE ÇEVİRİ BİLGE KURT TORUN HAYATİ TORUN TARİH VAKFI YURT YAYINLARI İÇİNDEKİLER ÖNSÖZ vü I. BÖLÜM: ALEVİ KİMLİĞİ ÜZERİNE 1 Bektaşilik/Kızılbaşlık: Tarihsel Bölünme ve Sonuçlan 3 irene Melikoff Bosna Bektaşîliği Üzerine 13 Erik Cornell Antropoloji ve Etnisite: Yeni Alevi Hareketinde Etnografyanın Yeri 21 David Shcmklcmd Türkiye’de Alevilik ve Bektaşilikle İlgili Akademik ve Gazetecilik 34 Nitelikli Yayınlar Karin Vorhoff Alevi-Bektaşi İlahiyatının Günümüz Türkiye’sindeki İşlevi 73 Faruk Bilici Politik “Alevilik” ile Politik “Sünnilik”: Benzerlikler ve Zıtlıklar 86 Ruşen Çakır “Almancı” Kimliğinin Alevi Kimliğine -

Islamic Fundamentalism and the Problem of Insecurity in Nigeria: the Boko Haram Phenomenon

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 15, Issue 3 (Sep. - Oct. 2013), PP 43-53 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.Iosrjournals.Org Islamic Fundamentalism and the Problem of Insecurity in Nigeria: The Boko Haram Phenomenon 1 2 Ezeani Emmanuel Onyebuchi and Chilaka Francis Chigozie 1Department of Political Science University of Nigeria, Nsukka, 2Department of Political Science University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Abstract: The article explored the impact of Islamic fundamentalism as typified by Boko Haram on insecurity in Nigeria. Using Huntington’s theory of clash of civilizations, the article argued that the rise of Boko Haram with its violent disposition against Western values is a counter response to Western civilization that is fast eclipsing other civilizations. The article notes that the wanton destruction of lives and properties by the Boko Haram sect constitutes a major threat to national security. It recommends that the Nigerian government should as a matter of urgency mobilize the whole panoply of its security architecture to checkmate the activities of Boko Haram. More importantly, the government should explore and intensify efforts at finding a political solution to the problem through dialogue. Keywords- Boko Haram, Civilization, Fundamentalism, Islam, Insecurity I. Introduction Many renowned scholars such as Karl Marx and Nietzsche had views that were vitriolic against religion. Marx (1844) canvassed for the abolition of religion because it is antithetic to genuine human happiness. For him, therefore, the abolition of religion is required for real happiness. However, since religion is considered as a private affair, the position of Marx and others who share his views have been overlooked. -

Understanding the Twists and Turns of Terrorism Among Muslims in the Nigerian Experience: an Assessment

Journal of Religion and Theology Volume 2, Issue 1, 2018, PP 1-15 Understanding the Twists and Turns of Terrorism among Muslims in the Nigerian Experience: An Assessment Ojo Joseph Rapheal Department of Religion and African Culture, Adekunle Ajasin University, P.M.B. 001, Akungba, Akoko, Ondo State, Nigeria, West Africa *Corresponding Authors: Ojo Joseph Rapheal, Department of Religion and African Culture, Adekunle Ajasin University, P.M.B. 001, Akungba, Akoko, Ondo State, Nigeria, West Africa ABSTRACT The history of humanity is replete with different acts of terrorism across ages and civilizations which takes different forms but fundamentally, they reflect man‟s inhumanity to man. Basically, different ideologies form the basis for such heinous acts. Nigeria, being a pluralistic society that is predominantly Muslims and Christians, has been faced with different forms of religious fundamentalism, extremism and terrorist attacks in the past four decades especially arising from some sects under the guise of promoting Islamic ideology for the establishment of „Islamic State‟ across the length and breadth of Nigeria. Engaging this issue through the historical, phenomenological and sociological research approaches, it was discovered that most of these acts of religious radicalism, extremism and terrorism are often hinged on religious and ideological manipulation, ignorance, poverty, absence of functional structure that promotes the operation of rule of law, thus increasing the frequency of violence and its effects. The work therefore recommended among other things the de-emphasizing of religious exclusivism, deconstruction of the age-long theologies of absolute truth claim, e.t.c. The conclusion of the work is that, dignity of humanity must take precedence over every religious contravening ideology that often leads to brutality and dehumanization of fellow human beings. -

Nigeria Assessing Risks to Stability

ISBN 978-0-89206-640-7 a report of the csis Ë|xHSKITCy066407zv*:+:!:+:! africa program Nigeria assessing risks to stability 1800 K Street, NW | Washington, DC 20006 Tel: (202) 887-0200 | Fax: (202) 775-3199 Author E-mail: [email protected] | Web: www.csis.org Peter M. Lewis Project Directors Jennifer G. Cooke Richard Downie June 2011 a report of the csis africa program Nigeria assessing risks to stability Author Peter M. Lewis Project Directors Jennifer G. Cooke Richard Downie June 2011 About CSIS At a time of new global opportunities and challenges, the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) provides strategic insights and bipartisan policy solutions to decisionmakers in government, international institutions, the private sector, and civil society. A bipartisan, nonprofit organization headquartered in Washington, D.C., CSIS conducts research and analysis and devel- ops policy initiatives that look into the future and anticipate change. Founded by David M. Abshire and Admiral Arleigh Burke at the height of the Cold War, CSIS was dedicated to finding ways for America to sustain its prominence and prosperity as a force for good in the world. Since 1962, CSIS has grown to become one of the world’s preeminent international policy institutions, with more than 220 full-time staff and a large network of affiliated scholars focused on defense and security, regional stability, and transnational challenges ranging from energy and climate to global development and economic integration. Former U.S. senator Sam Nunn became chairman of the CSIS Board of Trustees in 1999, and John J. Hamre has led CSIS as its president and chief executive officer since 2000. -

Religiousfreedom

RELIGIOUS FREEDOM WORLD REPORT 2010-2011 Public Affairs and Religious Liberty 12501 Old Columbia Pike Silver Spring, MD 20904 USA RELIGIOUS FREEDOM WORLD REPORT 2010-2011 Public Affairs and Religious Liberty 12501 Old Columbia Pike Silver Spring, MD 20904 USA T a b le of contents Foreward 5 IntroductIon 6 countrIes LIsted aLphabetIcally 8 countrIes 12 sources 310 the seventh-day adventIst church & religIous Freedom 313 thank you 314 contact InFormatIon 315 Foreward This report has come a long ways from our initial endeavor to document the state of religious freedom in the world with a focus on the Seventh-day Adventist experience. In an increasingly interrelated global world, a systemic approach to religious freedom in the context of human rights is warranted and requires a broader, multidisciplinary approach. For this report, Dr Diop has chosen a multifaceted approach. A section entitled “perspectives on current issues” provides succinct information that sheds light on major human rights and freedom of religion or belief issues from economic, political, social, cultural, and religious perspectives. Violations of human rights always occur in contexts where all these perspectives are woven together. In other words, each country provides a unique context where several factors are intertwined. Disentangling these factors helps us to better understand the real challenges a given country faces. More than 70% of the world population lives under some form of restriction to religious freedom. Where there is no separation of religion and state, freedoms are restricted. Though we defend religious freedom for people of all beliefs, approximately 75% of the people persecuted for their faith are Christian. -

Permissible Limitations to Freedom of Religion and Belief in Nigeria

Religion Religion and Human Rights 15 (2020) 57–76 Human Rights brill.com/rhrs Permissible Limitations to Freedom of Religion and Belief in Nigeria Ahmed Salisu Garba Bauchi State University, Gadau [email protected] Abstract The application of permissible limitations to restrict freedom of religion and belief in Nigeria continues to generate debate among scholars. This article applies a socio-legal methodology to analyse the legal rationale that Nigerian courts have used in cases con- cerning limitations to freedom of religion or belief. First, the article explores the history of the legal frameworks for the protection of freedom of religion and belief including its limitation in Nigeria. Second, the article analyses Nigerian courts’ interpretation of the concept with specific reference to the legal rational used. Third, the article inves- tigates the application of the proportionality test to balance the regulatory power of the state and citizens’ right to practice their religion. The article engages with case-law on freedom of religion, mostly from High courts and Court of Appeal in Nigeria. The article contains contributions from several scholars, religious groups, public officials, Non-Governmental Organisations obtained through interviews at their various offices. Keywords Nigeria – freedom of religion or belief – limitation clauses * Ahmed Salisu Garba holds a PhD Degree in Public Law and has written and presented pa- pers at different international conferences in the UK, USA and African Countries on Law and Religion related topics. He is also the Dean of Law/Head of Department of Private and Business Law at the Faculty of Law, Bauchi State University, Gadau in Nigeria. -

A History of Religious Violence in Nigeria: Grounds for A

A HISTORY OF RELIGIOUS VIOLENCE IN NIGERIA: GROUNDS FOR A MUTUAL CO-EXISTENCE BETWEEN CHRISTIANS AND MUSLIMS A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Department of Religious Studies University of the West In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy by Bede E. Inekwere Spring 2015 APPROVAL PAGE FOR GRADUATE Approved and recommended for acceptance as a dissertation in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Religious Studies. Bede E. Inekwere, Candidate 5/15/2015 A HISTORY OF RELIGIOUS VIOLENCE IN NIGERIA: GROUNDS FOR A MUTUAL CO-EXISTENCE BETWEEN CHRISTIANS AND MUSLIMS APPROVED: Jane Naomi Iwamura, Chair 5/15/2015 Zayn Kassam, Committee Member 5/15/2015 Joshua Capitanio, Committee 5/15/2015 Member I hereby declare that this dissertation has not been submitted as an exercise for a degree at any other institution, and that it is entirely my own work. © 2015 Bede E. Inekwere ALL RIGHTS RESERVE ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The completion of this work is of tremendous joy to me. I am grateful to God who made it possible. I wish to express my unreserved thanks to the many scholars and people who in various ways contributed to the successful completion of this dissertation. Top on the list are Drs. Jane Naomi Iwamura, Zayn Kassam (Pomona University) and Joshua Capitanio erudite scholars who painstakingly supervised the project. I am particularly grateful to professors in the Religious Studies Department at the University of the West who contributed in diverse ways towards my formation as a religious studies scholar. I remain indebted to Dr. -

Boko Haram: Nigeria's Extremist Islamic Sect

Reports BOKO HARAM: NIGERIA’S EXTREMIST ISLAMIC SECT Freedom C. Onuoha* Al Jazeera Centre for Studies Tel: +974-44663454 29 February 2012 [email protected] http://studies.aljazeera.net The extremist Islamic sect, Boko Haram, is now feared for its ability to mount both „low- scale‟ and audacious attacks in Nigeria. Since July 2009 when it provoked a short-lived anti-government uprising in northern Nigeria, the sect has mounted serial attacks that have placed it in media spotlight, both locally and internationally. What is the philosophy of this group? How did it emerge? What are its main operational tactics and their impact on security in Nigeria? And what are the future scenarios for the Nigerian government to deal with the threat? These questions are what this report attempts to address in a very concise manner. Evolution and Philosophy The exact date of the emergence of the Boko Haram sect is mired in controversy, especially if one relies on media accounts. Most local and foreign media trace its origin to 2002, when Mohammed Yusuf emerged as the leader of the sect. However, Nigerian security forces date the origin of the sect back to 1995, when Abubakar Lawan established the Ahlulsunna wal‟jama‟ah hijra sect at the University of Maduigiri, Borno State. It flourished as a non-violent movement until Mohammed Yusuf assumed leadership of the sect in 2002, shortly after Abubakar Lawan left to pursue further studies in Saudi Arabia. Since then, the sect has metamorphosed under various names like the Muhajirun, Yusufiyyah, Nigerian Taliban, Boko Haram and Jama‟atu Ahlissunnah lidda‟awati wal Jihad. -

Making Sense of Resilience in the Boko Haram Crisis Akinola Olojo

Making sense of resilience in the Boko Haram crisis Akinola Olojo Major risk factors for violent extremism can be found in Bauchi and Gombe, two states in the north-east of Nigeria – the zone where the terror group Boko Haram is active. Yet in spite of risk factors, these two states have not experienced similar levels of violent extremism as other states in the same geographical zone. This study explains the synergy of issues that have shaped the narrative of resilience in Bauchi and Gombe over the last decade. WEST AFRICA REPORT 30 | JUNE 2020 Key findings Ethnic affiliation can be an important mobilisation and the organisations they lead have the skills factor for terror groups seeking to exploit it within required to address this concern. a geographical space. This has been the case with The unconventional nature of the war against terror Boko Haram and the Kanuri people in the countries of the Lake Chad Basin. groups such as Boko Haram can benefit from the contribution of community-based groups, such as Traditional institutions are an indispensable part vigilante organisations. of a society’s resilience framework. Their historical origins enable them to convey the depth of legitimacy Armed responses by the state play an essential role, required for communities to mobilise. but their limits are evident in a complex insurgency The ideological component of terrorism is as much that requires multiple levels of management to a threat as the violence it inspires. Religious leaders address the threat posed. Recommendations Traditional institutions such as the Bauchi and This creates a platform to facilitate dialogue as a way Gombe emirates, as well as local authorities at the of resolving disagreements before they escalate to district, ward and village level, should strengthen physical violence. -

Instability in Nigeria: the Domestic Factors

INSTABILITY IN NIGERIA: THE DOMESTIC FACTORS SELECT CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS FROM “THREATS TO NIGERIA’S SECURITY: BOKO HARAM AND BEYOND” JUNE 19, 2012 Select Panel Summary “Instability in Nigeria: The Domestic Factors” From the Conference: Threats to Nigeria’s Security: Boko Haram and Beyond Tuesday, June 19, 2012 8:00 A.M. to 12:00 P.M. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace 1779 Massachusetts Avenue NW Washington, DC 20036 Domestic Factors of Instability in Nigeria Edited by Caitlin Alyce Buckley Threats to Nigeria’s Security: Boko Haram and Beyond Jamestown Foundation Conference, Washington D.C. - June 19, 2012 Panel One: Domestic Factors of Instability in Nigeria Jacob Zenn “Instability in Northern Nigeria: The View from the Ground” Jamestown Analyst for West African Affairs Dibussi Tande “Beyond Boko Haram: The Rise of Radical/Militant/Extremism Islam in Nigeria & Cameroon” Journalist & Blogger on Nigerian Security Issues Dr. Andrew McGregor “Central African Militant Movements: The Northern Nigeria, Niger, Chad, and Cameroon Nexus” The Jamestown Foundation Editor in Chief, Global Terrorism Analysis Mark McNamee “The Niger Delta & The Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta (MEND)” Analyst, The Jamestown Foundation Executive Summary Though Nigeria adopted a constitution in 1999, the country remains plagued with domes- tic instability and violence perpetrated by militant groups. Increased media attention has been given to a militant group that the media named Boko Haram. The group, which calls it- self Jama’atu Ahlis Sunna Lidda’awati wal-Jihad. According to the classical narrative the group emerged in protest of social inequality, political marginalization and economic ne- glect. Boko Haram is just one of many militant groups such as MEND, which belong to Nige- ria’s long history of military Islam. -

An Ottoman Traveller

AN OTTOMAN TRAVELLER SELECTIONS FROM THE Book of Travels of Evliya Çelebi TRANSLATION AND COMMENTARY BY Robert Dankoff and Sooyong Kim First published by Eland Publishing Limited 61 Exmouth Market, London EC1R 4QL in 2010 and in paperback in 2011 This ebook edition first published in 2011 All rights reserved Translation and Commentary copyright © Robert Dankoff and Sooyong Kim except where credited in the text, acknowledgements and bibliography The right of Robert Dankoff and Sooyong Kim to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly ISBN 978–1–78060–025–3 Cover Image: ‘Iskandar lies dying’ from the Tarjumah-i Shâhnâmah © Spencer Collection, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations Contents ILLUSTRATIONS ix INTRODUCTION x VOLUME ONE Istanbul 1 1. Introduction: The dream 3 2. The Süleymaniye Mosque 8 3. The antiquity of smoking 16 4. Galata 17 5. Kağıthane 21 6. Guilds’ parade 24 7. Lağari Hasan Çelebi 30 VOLUME TWO Anatolia and beyond 31 1. Setting out 33 2. -

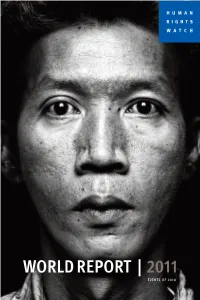

WORLDREPORT Rights to Ensure That the Quest for Cooperation Does Not Become an Excuse for Inaction

HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH WORLD REPOR T | 2011 EVENTS OF 2010 HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH WORLD REPORT 2011 EVENTS OF 2010 Copyright © 2011 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN-13: 978-1-58322-921-7 Front cover photo: Aung Myo Thein, 42, spent more than six years in prison in Burma for his activism as a student union leader. More than 2,200 political prisoners—including artists, journalists, students, monks, and political activists—remain locked up in Burma's squalid prisons. © 2010 Platon for Human Rights Watch Back cover photo: A child migrant worker from Kyrgyzstan picks tobacco leaves in Kazakhstan. Every year thousands of Kyrgyz migrant workers, often together with their chil- dren, find work in tobacco farming, where many are subjected to abuse and exploitation by employers. © 2009 Moises Saman/Magnum for Human Rights Watch Cover and book design by Rafael Jiménez 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor 51 Avenue Blanc, Floor 6, New York, NY 10118-3299 USA 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +1 212 290 4700 Tel: +41 22 738 0481 Fax: +1 212 736 1300 Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Poststraße 4-5 Washington, DC 20009 USA 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +1 202 612 4321 Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10 Fax: +1 202 612 4333 Fax: +49 30 2593 06-29 [email protected] [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor 1st fl, Wilds View London N1 9HF, UK Isle of Houghton Tel: +44 20 7713 1995 Boundary Road (at Carse O’Gowrie) Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 Parktown, 2198 South Africa [email protected] Tel: +27-11-484-2640, Fax: +27-11-484-2641 27 Rue de Lisbonne #4A, Meiji University Academy Common bldg.