Washington State Equity Plan: Ensuring Equitable Access to Excellent Educators

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guam Esfgov Initial Report

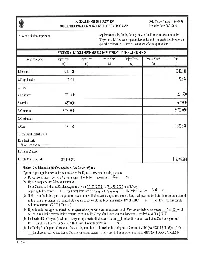

Education Stabilization Fund Program Outlying Areas-Governors CFDA Number: 84.425H Guam – $12,499,963 August 17, 2020 AMENDED October 22, 2020 ESF PROGRAM OUTLYING AREAS-GOVERNORS: GUAM Table of Contents Part I: Budget Process .............................................................................................................................. 3 Timeline ............................................................................................................................................... 3 Criteria, Process, and Deliberations ..................................................................................................... 3 Funding Mechanisms ........................................................................................................................... 4 Part II: ED Form 524 ............................................................................................................................... 5 Section A: Budget Summary ............................................................................................................... 5 Section B: N/A ..................................................................................................................................... 5 Section C: Budget Narrative: ............................................................................................................... 5 Sub-recipient: Guam Department of Education – $8,932,000 ......................................................... 5 Sub-recipient: University of Guam – $956,900 .............................................................................. -

State Systemic Improvement Plan – Phase I State of Washington Part B

State Systemic Improvement Plan – Phase I State of Washington Part B The Office of the Superintendent of Public Instruction, serving as the State Educational Agency (SEA) has completed Phase I of the Washington State Systemic Improvement Plan (SSIP). Phase I is part of a three-stage process for the development and implementation of a multi-year plan to improve educational results for students with disabilities. This multi-year plan is one of seventeen performance indicators (Indicator B17) required by the Office of Special Education Programs (OSEP) to be included in each state’s respective State Performance Plan/Annual Performance Report. Both internal SEA representatives and external stakeholders (see Attachment F) were directly engaged throughout all aspects of Phase I (Analysis) activities; this broad agency, community, and parental involvement will continue throughout Phase II (Development) and Phase III (Implementation and Evaluation) of the multi-year plan. Washington State’s Phase I report includes detailed analyses of key elements of the state’s general supervisory system which guided the selection of four primary improvement strategies designed to strengthen state and regional capacity to support district implementation of evidence-based practices to increase early literacy skills of students with disabilities. Specifically, Washington’s State-identified Measurable Result (SiMR) is designed to reduce the early literacy performance gap between kindergartners with disabilities and their typically developing peers. The Washington Kindergarten Inventory of Developing Skills (WaKIDS) entrance assessment will be used as the primary performance measure, with secondary impact and sustainability measures tracked through 1) Consistency Index scores from kindergarten through second grade, and 2) assessment data from the third grade State English-Language Arts assessment. -

Documentcommon Core of Data Local Education Agency Universe

NCES 2011-349rev U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Documentation to the NCES Common Core of Data Local Education Agency Universe Survey: School Year 2009–10 Version Provisional 2a Documentation to the NCES Common Core of Data Local Education Agency Universe Survey: School Year 2009–10 Version Provisional 2a August 2012 Patrick Keaton National Center for Education Statistics Jennifer Sable Education Statistics Services Institute – American Institutes for Research Fei Liu Education Statistics Services Institute – MacroSys LLC NCES 2011-349rev U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION U.S. Department of Education Arne Duncan Secretary Institute of Education Sciences John Q. Easton Director National Center for Education Statistics Jack Buckley Commissioner Elementary/Secondary & Libraries Studies Division Jeffrey Owings Associate Commissioner The National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) is the primary federal entity for collecting, analyzing, and reporting data related to education in the United States and other nations. It fulfills a congressional mandate to collect, collate, analyze, and report full and complete statistics on the condition of education in the United States; conduct and publish reports and specialized analyses of the meaning and significance of such statistics; assist state and local education agencies in improving their statistical systems; and review and report on education activities in foreign countries. NCES activities are designed to address high-priority education data needs; provide consistent, reliable, complete, and accurate indicators of education status and trends; and report timely, useful, and high-quality data to the U.S. Department of Education, the Congress, the states, other education policymakers, practitioners, data users, and the general public. Unless specifically noted, all information contained herein is in the public domain. -

Indiana Final Consolidated State Plan (PDF)

State Template for the Consolidated State Plan Under the Every Student Succeeds Act U.S. Department of Education OMB Number: 1810-0576 Expiration Date: November 30, 2019 Cover Page Contact Information and Signatures SEA Contact (Name and Position): Telephone: Lee Ann Kwiatkowski, Chief of Staff (317) 234-6904 Mailing Address: Email Address: 115 W. Washington Street, Suite 600 [email protected] Indianapolis, IN 46204 By signing this document, I assure that: To the best of my knowledge and belief, all information and data included in this plan are true and correct. The SEA will submit a comprehensive set of assurances at a date and time established by the Secretary, including the assurances in ESEA section 8304. Consistent with ESEA section 8302(b)(3), the SEA will meet the requirements of ESEA sections 1117 and 8501 regarding the participation of private school children and teachers. Authorized SEA Representative (Printed Name) Telephone: Superintendent Jennifer McCormick (317) 232-6610 Signature of Authorized SEA Representative Date: January 8, 2018 Governor (Printed Name) Date SEA provided plan to the Governor under ESEA section 8540: Signature of Governor Date: The SEA, through its authorized representative, agrees to the enclosed assurances. 2 Table of Contents Guide to Completing Revised Consolidated State Plan Template…………………………………………...…6 Letter to Secretary DeVos………………………………………………………………………………………8 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………………………..9 Instruction for Completing the Consolidated State Plan………………………………………………..……..10 Programs Included in the Consolidated State Plan…………………………………………………………….11 Section 1: Long-term Goals………………………………………………………………………………….13 A. Academic Achievement…………………………………………………………………...13 B. Graduation Rate…………………………………………………………………………...16 C. English Language Proficiency…………………………………………………………....18 Section 2: Consultation…………………………………………...…………………………,,,,,…………....21 A. Public Notice……………………………………………………………………………..22 B. Outreach and Input………………………………………………………………….……21 C. -

New Jersey State Profile

SHAPE OF THE NATION™ Unless otherwise noted with a specific legal citation, state profile information is sourced solely from responses to a survey of physical education specialists in state departments of education. 2016 STATE Profile NEW JERSEY Amount of Required Physical Education: The state requires Comprehensive Health and Physical Education were last revised students to take 150 minutes per week of “health, safety and in 2014. physical education” in elementary, middle school/junior high, and Areas addressed in the state standards include: high school.210 High school students must earn physical education credit for graduation. The requirements are enforced using a National Standard 1: Competency in a variety of motor skills department monitoring/review process. and movement patterns Physical Education Equipment and Facilities: The state National Standard 2: Knowledge of concepts, principles, does not annually assess the availability of appropriate equipment strategies and tactics related to movement and performance and adequate facilities for students to engage in required physical National Standard 3: Knowledge and skills to achieve and education instruction. maintain a health-enhancing level of physical activity and fitness High School Graduation Requirements: District boards are National Standard 4: Responsible personal and social required to develop and implement local graduation requirements behavior that respects self and others that include 3.75 credits in health, safety, and physical education during each year of enrollment, distributed as 150 minutes per National Standard 5: Value of physical activity for health, 211 week. enjoyment, challenge, self-expression and/or social interaction Substitutions: The state permits school districts or schools State Curriculum: The state requires school districts and schools to allow students to substitute other activities for their required to use a curriculum aligned with the state standards for physical physical education credits. -

Sinseru Yan Minagåhet

[email protected] From: Speaker's Office <[email protected]> Sent: Wednesday, December 23, 2020 9:10 AM To: Clerks Office Cc: Rennae Meno Subject: M&C Fwd: GEB December 22, 2020 Special Meeting - Reporting Requirements Attachments: GEB Reporting Requirements December 22, 2020 meeting.pdf Agenda, Minutes, and other Documents for Department of Education- 7:45 Guam Education Board Special Meeting Office of the 35GL- 12/23/20 AM 12/22/20 held on December 22, 2020.* Superintendent 20-2536 Sinseru yan Minagåhet, Office of the Speaker ● Tina Rose Muña Barnes Committee on Public Accountability, Human Resources & the Guam Buildup 35th Guam Legislature I Mina’trentai Singko na Liheslaturan Guåhan Guam Congress Building | 163 Chalan Santo Papa | Hagatna, GU 96910 T: (671) 477-2520/1 [email protected] This e-mail message is intended only for the use of the individual or entity named above and may contain confidential and privileged information. If you are not the intended recipient, any disclosure, copying, distribution or use of the information contained in this transmission is strictly PROHIBITED. If you have received this transmission in error, please immediately notify us by replying to [email protected] and delete the message immediately. Thank you very much. Gumai pribilehu yan konfedensia este siha na mensåhi. Solo espesiåtmente para hågu ma entensioña pat ma aturisa para unrisibi. Sen prubidu kumu ti un ma aturisa para manribisa, na’setbe, pat mandespåtcha. Yanggen lachi rinisibu-mu nu este na mensåhi , put fabot ago’ guatu gi I numa’huyong gi as [email protected] yan despues destrosa todu siha I kopian mensåhi. -

Arizona Educational Acronyms

Arizona Educational Acronyms A AAC – Arizona Administrative Code AACO – Arizona Association of Counties AACSS - Arizona Association of County School Superintendents AAG- Accountability Advisory Group AASBO – Arizona Association of School Business Officials ABIL - Arizona Bridge to Independent Living ADA - American's with Disabilities Act ADD - Attention Deficit Disorder ADE - Arizona Department of Education ADE/ESS - ADE Exceptional Student Services ADE/PINS - ADE Parent Information Network Specialists ADHD - Attention Deficit with Hyperactivity Disorder ADHS - Arizona Department of Health Services ADL - Activities of Daily Living ADM – Average Daily Membership AEA – Arizona Education Association AESA – Association of Education Service Agencies AFR – Annual Financial Report AG - Auditor General or Attorney General AGO – Attorney General Opinion Alt. AAG - Alternative Education Accountability Advisory Group AOC – Administrative Office of the Courts (of the Arizona Supreme Court) APE - Adaptive Physical Education ARS – Arizona Revised Statutes ARSA- Arizona Rural Schools Association ASA – Arizona School Administrators ASBA- Arizona School Boards Association ASU - Arizona State University AT - Assistive Technology ATRA – Arizona Tax Research Association AZELLA – Arizona English Language Learners Assessment AZ-TAP - Arizona Technology Access Program B BHS - Behavioral Health Services BIP - Behavior Intervention Plan C CAC – Certification Advisory Committee CCR – College and Career Readiness CCRI – College and Career Readiness Indicator CEAC -

Indiana English Language Learner Identification and Placement Guidance Document 2021-22

Indiana English Language Learner Identification and Placement Guidance Document 2021-22 This document contains guidance on the identification and placement process for newly arrived English language learners in your state. WIDA and your state education agency have worked together to provide this outline of policies, procedures, assessment options, test administrator training requirements, and criteria for placement in ELL services. This document is updated each spring and throughout the year per SEA request. For questions related to state policy, please contact: Office of Student Assessment Office of Title Grants and Support Indiana Department of Education IDOE: English Learning and Migrant Education [email protected] 317-232-9050 For questions related to WIDA’s website, resources, or assessments, please contact the WIDA Client Services Center at [email protected] or (866) 276- 7735. Initial Assessment and Identification Questions/Topic State-specific Guidance Process Overview The key steps corporations/schools must take for identifying a student as an English learner (EL) and placement in an EL program include: Home Language Survey (HLS): Administration of an initial HLS or acquisition of the original HLS to determine Language Minority (LM) status. WIDA Placement Assessment: Administration of the appropriate WIDA placement assessment (Kindergarten W-APT or WIDA Screener) for newly identified Language Minority (LM) students. Prior WIDA Assessment Data: Acquisition of prior WIDA assessment results (placement or ACCESS) if the student transferred from another Indiana school or WIDA Consortium Member State. Results less than one year old can be utilized for identification and placement purposes. Entrance Criteria: If the student meets Indiana entrance criteria, the student is identified as an EL and placed in the EL program. -

Review of 2008-09 Online Courses and Programs

Review of 2008–09 Online Courses and Programs Report to the Legislature Randy I. Dorn State Superintendent of Public Instruction December 2009 Review of 2008–09 Online Courses and Programs Prepared by: Karl Nelson, Assistant Director, Digital Learning Department Digital Learning Department Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction Judy Margrath-Huge, Director Randy I. Dorn Superintendent of Public Instruction Ken Kanikeberg Chief of Staff Alan Burke, Ed.D. Deputy Superintendent, K–12 Education Martin T. Mueller Assistant Superintendent, Student Support December 2009 Table of Contents Executive Summary ......................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 4 Process ............................................................................................................................................. 5 Definitions ................................................................................................................................... 5 Categories of Courses and Programs .......................................................................................... 5 Scope ........................................................................................................................................... 7 Data Sources ............................................................................................................................... -

Examining Teacher Retention and Mobility in Small and Rural Districts in Washington State

Examining Teacher Retention and Mobility in Small and Rural Districts in Washington State Ana M. Elfers Margaret L. Plecki With the assistance of Michelle McGowan Rena S. H. Kido Michael Schulze-Oechtering University of Washington College of Education Educational Leadership and Policy Studies November 2006 Table of Contents Executive Summary......................................................................................................... iii I. Introduction ...................................................................................................................1 II. Research Questions......................................................................................................1 III. Background: The Unique Challenges Facing Small and Rural Districts ............1 IV. Overall Approach and Methods................................................................................2 V. Defining Terms.............................................................................................................3 VI. Selection of Districts for the Sample.........................................................................4 VII. Findings......................................................................................................................6 A. Characteristics of Teachers in Small and Rural Districts as Compared to the State.....................................................................................6 B. Retention and Mobility of Teachers in Small and Rural Districts ..............8 C. Retention and -

SMU Law Review Education

SMU Law Review Volume 49 Issue 4 Annual Survey of Texas Law Article 12 1996 Education Ellen Williams Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/smulr Recommended Citation Ellen Williams, Education, 49 SMU L. REV. 901 (1996) https://scholar.smu.edu/smulr/vol49/iss4/12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in SMU Law Review by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. EDUCATION Ellen Williams* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ........................................ 902 II. GOVERNANCE .......................................... 904 A . STATE ................................................. 904 1. Rulem aking ....................................... 905 2. A ppeals ........................................... 905 3. Waivers ........................................... 906 B . R EGIONAL ............................................ 907 C. LOCAL-SCHOOL DISTRICrs ........................... 907 1. Typ es .............................................. 907 2. Creation, Detachment and Annexation, and Consolidation ..................................... 908 3. Composition and Elections of Boards of Trustees .. 909 4. Powers and D uties ................................. 910 D. LOCAL-CHARTERS ................................... 912 1. Home-Rule School District Charter ................ 913 2. Campus or Campus Program Charter ............. 915 3. Open-Enrollment Charter School -

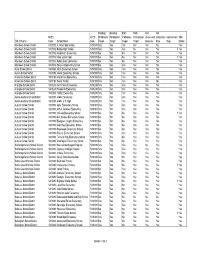

District Name NCES Code School Name NCES Code Reading

Reading Reading Math Math Met Met NCES NCES Proficiency Participation Proficiency Participation Unexcused Graduation Improvement Title I District Name Code School Name Code Target Target Target Target Absence Rate Step School Aberdeen School District 5300030 A J West Elementary 5300030 Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Aberdeen School District 5300030 Harbor High School 5300030 Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes 4 Yes Aberdeen School District 5300030 Mcdermoth Elementary 5300030 No Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes Aberdeen School District 5300030 Miller Junior High 5300030 No Yes No Yes Yes Yes 1 Yes Aberdeen School District 5300030 Robert Gray Elementary 5300030 No Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes Aberdeen School District 5300030 Stevens Elementary School 5300030 No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Adna School District 5300060 Adna Elementary School 5300060 Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Almira School District 5300090 Almira Elementary School 5300090 Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Anacortes School District 5300150 Island View Elementary 5300150 Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Anacortes School District 5300150 Secret Harbor 5300150 Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No Yes Arlington School District 5300240 Kent Prairie Elementary 5300240 Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Arlington School District 5300240 Presidents Elementary 5300240 Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Arlington School District 5300240 Trafton Elementary 5300240 Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Asotin-Anatone School District 5300280 Asotin Elementary 5300280 Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Asotin-Anatone School District 5300280 Asotin Jr Sr High 5300280 Yes Yes