Review of 2008-09 Online Courses and Programs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Washington State Equity Plan: Ensuring Equitable Access to Excellent Educators

Randy I. Dorn • State Superintendent Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction Old Capitol Building • P.O. Box 47200 Olympia, WA 98504-7200 Washington State Equity Plan: Ensuring Equitable Access to Excellent Educators 2015 Authorizing legislation: Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) - Section 1111 (b)(8)(C) Title II, Part A at OSPI Gayle Pauley, Assistant Superintendent of Special Programs and Federal Accountability, Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction Prepared by: Maria Flores, Director, Title II, Part A and Special Programs Kaori Strunk, Data Analyst, Title II, Part A and Special Programs TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 4 Excellent Educator Definition ..................................................................................................................... 13 Stakeholder Engagement ............................................................................................................................ 16 Review of Research ..................................................................................................................................... 28 Equity Gap Data Analysis ............................................................................................................................ 29 Strategies for Eliminating Equity Gaps ....................................................................................................... -

Examining Teacher Retention and Mobility in Small and Rural Districts in Washington State

Examining Teacher Retention and Mobility in Small and Rural Districts in Washington State Ana M. Elfers Margaret L. Plecki With the assistance of Michelle McGowan Rena S. H. Kido Michael Schulze-Oechtering University of Washington College of Education Educational Leadership and Policy Studies November 2006 Table of Contents Executive Summary......................................................................................................... iii I. Introduction ...................................................................................................................1 II. Research Questions......................................................................................................1 III. Background: The Unique Challenges Facing Small and Rural Districts ............1 IV. Overall Approach and Methods................................................................................2 V. Defining Terms.............................................................................................................3 VI. Selection of Districts for the Sample.........................................................................4 VII. Findings......................................................................................................................6 A. Characteristics of Teachers in Small and Rural Districts as Compared to the State.....................................................................................6 B. Retention and Mobility of Teachers in Small and Rural Districts ..............8 C. Retention and -

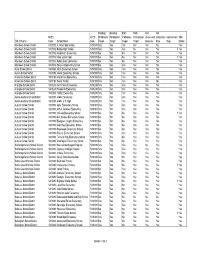

District Name NCES Code School Name NCES Code Reading

Reading Reading Math Math Met Met NCES NCES Proficiency Participation Proficiency Participation Unexcused Graduation Improvement Title I District Name Code School Name Code Target Target Target Target Absence Rate Step School Aberdeen School District 5300030 A J West Elementary 5300030 Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Aberdeen School District 5300030 Harbor High School 5300030 Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes 4 Yes Aberdeen School District 5300030 Mcdermoth Elementary 5300030 No Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes Aberdeen School District 5300030 Miller Junior High 5300030 No Yes No Yes Yes Yes 1 Yes Aberdeen School District 5300030 Robert Gray Elementary 5300030 No Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes Aberdeen School District 5300030 Stevens Elementary School 5300030 No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Adna School District 5300060 Adna Elementary School 5300060 Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Almira School District 5300090 Almira Elementary School 5300090 Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Anacortes School District 5300150 Island View Elementary 5300150 Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Anacortes School District 5300150 Secret Harbor 5300150 Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No Yes Arlington School District 5300240 Kent Prairie Elementary 5300240 Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Arlington School District 5300240 Presidents Elementary 5300240 Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Arlington School District 5300240 Trafton Elementary 5300240 Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Asotin-Anatone School District 5300280 Asotin Elementary 5300280 Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Asotin-Anatone School District 5300280 Asotin Jr Sr High 5300280 Yes Yes -

Sequoia Union High School District 480 James Avenue Redwood City, California 94062

A Proposal Prepared for SSeeqquuooiiaa UUnniioonn HHiigghh SScchhooooll DDiissttrriicctt RReeddwwoooodd CCiittyy,, CCaalliiffoorrnniiaa for The Search and Selection of a Superintendent of Schools submitted in collaboration with by Executive Recruitment & Development Phone: 888-375-4814 Email: [email protected] Website: www.macnjake.com November 6, 2020 Board of Trustees Sequoia Union High School District 480 James Avenue Redwood City, California 94062 Thank you for the opportunity to present our services to your board. The enclosed proposal describes the professional services the California School Board Association representative, McPherson & Jacobson, L.L.C. will provide Sequoia Union High School District in ensuring your superintendent search secures quality leadership for the district. McPherson & Jacobson will work with the board to design a search that meets the unique needs of your school district. Our firm’s five-phase protocol allows the board to concentrate on the most important segments: the interview and selection of the successful candidate. Our team of consultants, working in conjunction with the board and diverse stakeholder groups you identify, will implement a systematic, comprehensive process culminating in the hiring of the most qualified candidate for your district. At the core of our firm’s work is the belief that every student be entitled to high quality education and that this is dependent upon quality leadership. We understand that students have diverse needs, thus, we focus on the intentional recruitment of a diverse candidate pool that includes ethnic and cultural identity as well as experience in culturally proficient practices that have proven successful in addressing educational equity gaps. This unique approach is made possible through the diversity and extensive network of our consultants who have various levels of expertise in the school system from superintendents, to school board members, to educational equity experts in the field. -

Special Board Meeting

Shoreline School Board January 5, 2021 6:30 p.m. Due to Governor Inslee’s proclamation, there will not be a site for the public to attend this meeting other than electronically or telephonically Link: https://us02web.zoom.us/j/85295558954?pwd=ZWVhZWdhS0dYVVRjZTFxQTZZd08vdz09 Password: 376893 Call-in numbers: 1-253-215-8782 or 1-346-248-7799 Special Board Meeting Public Comments Submitted Online for January 5, 2021 Special Meeting No contact info- January 5, 2021 Special School Board Meeting Public Comment Form (Responses).pdf (p. 2) 1. Review Superintendent Search Proposals GRRecruiting-SHORELINE PUBLIC SCHOOLS PROPOSAL 12.15.15.pdf (p. 5) McPherson & Jacobson LLC Proposal for Shoreline Public Schools, WA, December 2020.pdf (p. 27) NW Leadership-Shoreline '21 proposal.pdf (p. 61) Ray and Associates-Shoreline Superintendent Proposal.pdf (p. 76) 2. Action Item: Selection of Superintendent Search Consultant 3. Adjournment: _________ p.m. Packet page 1 of 102 Name Relation to Shoreline Comment to School Board Public Schools (check all that apply) Steven Johnson Parent/Guardian As the parent of 3 boys who attend various schools in the Shoreline School District, I just wanted to first of all say thank you so much for your leadership to the students, staff, families, and community members of the Shoreline School District. After hearing that Superintendent Miner has decided to resign at the end of the year and as you search for a new superintendent which we know is not an easy job or process to complete and we thank you for your work on that, I wanted to give you some of my thoughts as a parent in the district of what I think the new superintendent should make sure they focus on/pay special attention to. -

2007 Title II Highe R Education Act Report

2006-2007 Title II Higher Education Act Report Reporting on the Quality of Teacher Preparation Title II Higher Education Act Presented to The Office of the Superintendent of Public Instruction State of Washington By The Center for Teaching and Learning College of Education and Professional Studies Central Washington University April 7, 2008 2006-2007 Title II Report: CWU TITLE II INSTITUTIONAL REPORT Annual Institutional Report on Teacher Preparation: Academic Year 2006-2007 Institution name: Central Washington University Respondent name: Connie Lambert, Ph.D. Respondent title: Interim Dean, College of Education and Professional Studies Phone number: 509-963-1411 Fax: 509-963-1049 E-Mail address: [email protected] Address: 400 East University Way City: Ellensburg State: Washington Zip code: 98926-7415 Section IA. Pass Rates Program completers for whom information should be provided are those completing residency certificate program requirements in the 2006-2007 academic year (September 1, 2006 – August 31, 2007). Do not include completers of alternative-route programs. Table 1: Single-Assessment Institution-Level Pass-rate Data: Regular Teacher Preparation Program, 2006-2007 Institution Name: Central Washington University Institutional Code: 4044 Number of program completers: 454 Number of program completers found, 438 matched, and used in passing rate calculations.1 Assess- # taking # passing Institutional Statewide Type of Assessment ment assessment assessment pass rate pass rate Code # Academic Content Areas (math, English, biology etc.) -

National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet - THORP GRADE SCHOOL KITTITAS COUNTY, WASHINGTON

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (Oct. 1990) RECEIV. >280 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service JUN -42009 National Register of Historic Places JitO^cuur HISTORIC PLA CES Registration Form NATIONAL PARK SERVICE This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property_____________________________________________________ Historic name Thorp Grade School Other names/site number 2. Location street & number 10831 N. Thorp HWY ___ ___ not for publication city or town __ Thorp ___ ___ vicinity State Washington code WA county Kittitas code 037 zip code 98946 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this _X nomination _ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property .Xfmeets _ does not meet the National Register criteria. -

SCHOOL DISTRICT of ALTOONA 9:01 AM 09/11/13 05.13.06.00.00-10.2-010079 Bi-Monthly Check List (Dates: 08/29/13 - 09/11/13) PAGE: 1

School District of 1903 Bartlett Avenue Altoona, WI 54720 715-839-6032 715-839-6066 FAX Altoona Dr. Connie Biedron, Superintendent www.altoona.k12.wi.us ALTOONA BOARD OF EDUCATION Regular Meeting Altoona Commons Addition September 16, 2013 7:00 p.m. Agenda 1. Call to Order 2. Roll Call 3. Reading of Public Notice 4. Pledge of Allegiance 5. Rules for Meeting 6. Approval of Minutes a. September 3, 2013 Regular Meeting 7. Public Participation (All remarks are to be addressed to the Board; discussion among citizens present is not permitted. Board members may ask questions of a speaker; however, no formal deliberations are allowed at this time.) a. Non-Agenda items - public comment and concern b. Agenda items - public comment and concern 8. Treasurer’s Report a. Approval of Checks for Payment (1) General fund checks totaling $471,288.89 (2) Student activity fund checks totaling $1,929.19 b. Approval of Treasurer’s Report 9. Information a. Committee Reports (1) Demographic Trends and Facilities Planning Committee, September 10 (a) Community Information Forum, October 8 (2) Budget Development Committee, September18 b. General Information c. President’s Report (1) Review Draft Board Goals (2) Meet and Greet Rotation Schedule (3) Legislative Breakfast, October 14 d. Superintendent’s Report (1) Homecoming Events (2) High School Proposal for Student Release Program under 1993 ACT 340 Altoona Board of Education, September 16, 2013 (3) ACT Report (4) Monthly Budget Update (5) Superintendent’s Conference, September 25-27 (6) Race to the Top Grant (7) Other Updates, News and Events 10. Board Action after Consideration and Discussion a. -

DC Capacity Expansion Data Sheet.Xlsx

9‐12 Dual Dual Credit District School Gr 9 Gr 10 Gr 11 Gr 12 9‐12 District Name School Name K‐12 Total Credit Allocation FRPL Rate Participation Code Code Total Total Total Total Total Students Rate 00000 State Summary 180,936 $ 2,487,643.00 14005 Aberdeen School District 3476 J M Weatherwax High School 926 223 246 222 224 915 711$ 10,000.00 53.92% 77.70% 14005 Aberdeen School District 5208 Twin Harbors, A Branch of New Market Skills Center 000000 47$ 1,900.00 0.00% 0.00% 21226 Adna School District 2441 Adna Middle/High School 339 55 45 42 41 183 92$ 2,037.00 29.46% 50.27% 29103 Anacortes School District 2467 Anacortes High School 849 224 212 217 196 849 741$ 10,000.00 29.05% 87.28% 31016 Arlington School District 1714 Stillaguamish School 270 22 9 27 36 94 21$ 1,900.00 27.36% 22.34% 31016 Arlington School District 2523 Arlington High School 1,566 435 393 366 372 1,566 705$ 10,000.00 28.96% 45.02% 31016 Arlington School District 4287 Weston High School 138 17 30 38 53 138 2$ 1,900.00 61.57% 1.45% 02420 Asotin‐Anatone School District 2434 Asotin Jr Sr High 271 50 43 40 43 176 91$ 2,025.00 37.68% 51.70% 17408 Auburn School District 2702 West Auburn Senior High School 228 7 42 94 85 228 38$ 1,900.00 66.02% 16.67% 17408 Auburn School District 2795 Auburn Senior High School 1,592 419 386 405 382 1,592 1120$ 10,000.00 57.95% 70.35% 17408 Auburn School District 4474 Auburn Riverside High School 1,618 411 409 425 373 1,618 1144$ 10,000.00 38.98% 70.70% 17408 Auburn School District 5037 Auburn Mountainview High School 1,490 361 433 392 304 1,490 -

Alumni History and Hall of Fame Project

Los Angeles Unified School District Alumni History and Hall of Fame Project Los Angeles Unified School District Alumni History and Hall of Fame Project Written and Edited by Bob and Sandy Collins All publication, duplication and distribution rights are donated to the Los Angeles Unified School District by the authors First Edition August 2016 Published in the United States i Alumni History and Hall of Fame Project Founding Committee and Contributors Sincere appreciation is extended to Ray Cortines, former LAUSD Superintendent of Schools, Michelle King, LAUSD Superintendent, and Nicole Elam, Chief of Staff for their ongoing support of this project. Appreciation is extended to the following members of the Founding Committee of the Alumni History and Hall of Fame Project for their expertise, insight and support. Jacob Aguilar, Roosevelt High School, Alumni Association Bob Collins, Chief Instructional Officer, Secondary, LAUSD (Retired) Sandy Collins, Principal, Columbus Middle School (Retired) Art Duardo, Principal, El Sereno Middle School (Retired) Nicole Elam, Chief of Staff Grant Francis, Venice High School (Retired) Shannon Haber, Director of Communication and Media Relations, LAUSD Bud Jacobs, Director, LAUSD High Schools and Principal, Venice High School (Retired) Michelle King, Superintendent Joyce Kleifeld, Los Angeles High School, Alumni Association, Harrison Trust Cynthia Lim, LAUSD, Director of Assessment Robin Lithgow, Theater Arts Advisor, LAUSD (Retired) Ellen Morgan, Public Information Officer Kenn Phillips, Business Community Carl J. Piper, LAUSD Legal Department Rory Pullens, Executive Director, LAUSD Arts Education Branch Belinda Stith, LAUSD Legal Department Tony White, Visual and Performing Arts Coordinator, LAUSD Beyond the Bell Branch Appreciation is also extended to the following schools, principals, assistant principals, staffs and alumni organizations for their support and contributions to this project. -

Public Schools

2020-2021 RESOURCE GUIDE FALL CONFERENCE EDITION OCTOBER 2020 INTRODUCTION This Resource Guide contains the names of individuals designated as having responsibility for Career and Technical Education in the public secondary schools and secondary skill centers in Washington State. All school districts are listed even if they do not have CTE programs. Also included are WACTA officers; WA-ACTE Executive Board; staff of OSPI, SBCTC, and WTECB; CTSO executive directors; and other WACTA members. This Resource Guide is possible through the efforts of WACTA and WA-ACTE. We hope that you will find it beneficial. The information in this Resource Guide is available for education purposes only and is not to be used commercially. Please send updates to: Tess Alviso WA-ACTE PO Box 315 Olympia WA 98507-0315 360-786-9286 Fax: 360-357-1491 [email protected] Save the Date WACTA Spring Conference February 22-23, 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction and Table of Contents ......................................................................................................................................................... 2 The History of WAVA ............................................................................................................................................................................ 3-7 The History of WACTA ............................................................................................................................................................................ 8 WACTA ...............................................................................................................................................................................................9-11 -

Development of K-12 Science Handbook for the Thorp School District Sim Egbert Central Washington University

Central Washington University ScholarWorks@CWU All Graduate Projects Graduate Student Projects 1982 Development of K-12 Science Handbook for the Thorp School District Sim Egbert Central Washington University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/graduate_projects Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons, and the Science and Mathematics Education Commons Recommended Citation Egbert, Sim, "Development of K-12 Science Handbook for the Thorp School District" (1982). All Graduate Projects. 43. http://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/graduate_projects/43 This Graduate Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Student Projects at ScholarWorks@CWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Projects by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@CWU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DEVELOPMENT OF K-12 SCIENCE HANDBOOK FOR THE THORP SCHOOL DISTRICT A Project Presented to The Graduate Faculty Central Washington University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Education by Sim Egbert December, 19 8 2 DEVELOPMENT OF K-12 SCIENCE HANDBOOK FOR THE THORP SCHOOL DISTRICT by Sim M. Egbert December, 198 2 A handbook was created for the Thorp School District to provide teachers with science goals and objectives for each grade level. A science philosophy, a sample evalua tion sheet, elementary science scope and sequence, a list of current textbooks, and the sequences of science classes ( were also presented in the handbook. Curriculum guides from several districts were studied before the goals and cbjectives were written for the handbook. The research on the needs of a curriculum and the past and current trends in science curriculum was reviewed.