Impact of Migration Law on the Development of Australian Administrative Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fact and Law Stephen Gageler

Fact and Law Stephen Gageler* I The essential elements of the decision-making process of a court are well understood and can be simply stated. The court finds the facts. The court ascertains the law. The court applies the law to the facts to decide the case. The distinction between finding the facts and ascertaining the law corresponds to the distinction in a common law court between the traditional roles of jury and judge. The court - traditionally the jury - finds the facts on the basis of evidence. The court - always the judge - ascertains the law with the benefit of argument. Ascertaining the law is a process of induction from one, or a combination, of two sources: the constitutional or statutory text and the previously decided cases. That distinction between finding the facts and ascertaining the law, together with that description of the process of ascertaining the law, works well enough for most purposes in most cases. * Solicitor-General of Australia. This paper was presented as the Sir N inian Stephen Lecture at the University of Newcastle on 14 August 2009. The Sir Ninian Stephen Lecture was established to mark the arrival of the first group of Bachelor of Laws students at the University of Newcastle in 1993. It is an annual event that is delivered by an eminent lawyer every academic year. 1 STEPHEN GAGELER (2008-9) But it can become blurred where the law to be ascertained is not clear or is not immutable. The principles of interpretation or precedent that govern the process of induction may in some courts and in some cases leave room for choice as to the meaning to be inferred from the constitutional or statutory text or as to the rule to be drawn from the previously decided cases. -

Ceremonial Sitting of the Tribunal for the Swearing in and Welcome of the Honourable Justice Kerr As President

AUSCRIPT AUSTRALASIA PTY LIMITED ABN 72 110 028 825 Level 22, 179 Turbot Street, Brisbane QLD 4000 PO Box 13038 George St Post Shop, Brisbane QLD 4003 T: 1800 AUSCRIPT (1800 287 274) F: 1300 739 037 E: [email protected] W: www.auscript.com.au TRANSCRIPT OF PROCEEDINGS O/N H-59979 ADMINISTRATIVE APPEALS TRIBUNAL CEREMONIAL SITTING OF THE TRIBUNAL FOR THE SWEARING IN AND WELCOME OF THE HONOURABLE JUSTICE KERR AS PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE JUSTICE KERR, President THE HONOURABLE JUSTICE KEANE, Chief Justice of the Federal Court of Australia THE HONOURABLE JUSTICE BUCHANAN, Presidential Member DEPUTY PRESIDENT S.D. HOTOP DEPUTY PRESIDENT R.P. HANDLEY DEPUTY PRESIDENT D.G. JARVIS THE HONOURABLE R.J. GROOM, Deputy President DEPUTY PRESIDENT P.E. HACK SC DEPUTY PRESIDENT J.W. CONSTANCE THE HONOURABLE B.J.M. TAMBERLIN QC, Deputy President DEPUTY PRESIDENT S.E. FROST DEPUTY PRESIDENT R. DEUTSCH PROF R.M. CREYKE, Senior Member MS G. ETTINGER, Senior Member MR P.W. TAYLOR SC, Senior Member MS J.F. TOOHEY, Senior Member MS A.K. BRITTON, Senior Member MR D. LETCHER SC, Senior Member MS J.L REDFERN PSM, Senior Member MS G. LAZANAS, Senior Member DR I.S. ALEXANDER, Member DR T.M. NICOLETTI, Member DR H. HAIKAL-MUKHTAR, Member DR M. COUCH, Member SYDNEY 9.32 AM, WEDNESDAY, 16 MAY 2012 .KERR 16.5.12 P-1 ©Commonwealth of Australia KERR J: Chief Justice, I have the honour to announce that I have received a commission from her Excellency, the Governor General, appointing me as President of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal. -

Review Essay Open Chambers: High Court Associates and Supreme Court Clerks Compared

REVIEW ESSAY OPEN CHAMBERS: HIGH COURT ASSOCIATES AND SUPREME COURT CLERKS COMPARED KATHARINE G YOUNG∗ Sorcerers’ Apprentices: 100 Years of Law Clerks at the United States Supreme Court by Artemus Ward and David L Weiden (New York: New York University Press, 2006) pages i–xiv, 1–358. Price A$65.00 (hardcover). ISBN 0 8147 9404 1. I They have been variously described as ‘junior justices’, ‘para-judges’, ‘pup- peteers’, ‘courtiers’, ‘ghost-writers’, ‘knuckleheads’ and ‘little beasts’. In a recent study of the role of law clerks in the United States Supreme Court, political scientists Artemus Ward and David L Weiden settle on a new metaphor. In Sorcerers’ Apprentices: 100 Years of Law Clerks at the United States Supreme Court, the authors borrow from Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s famous poem to describe the transformation of the institution of the law clerk over the course of a century, from benign pupilage to ‘a permanent bureaucracy of influential legal decision-makers’.1 The rise of the institution has in turn transformed the Court itself. Nonetheless, despite the extravagant metaphor, the authors do not set out to provide a new exposé on the internal politics of the Supreme Court or to unveil the clerks (or their justices) as errant magicians.2 Unlike Bob Woodward and Scott Armstrong’s The Brethren3 and Edward Lazarus’ Closed Chambers,4 Sorcerers’ Apprentices is not pitched to the public’s right to know (or its desire ∗ BA, LLB (Hons) (Melb), LLM Program (Harv); SJD Candidate and Clark Byse Teaching Fellow, Harvard Law School; Associate to Justice Michael Kirby AC CMG, High Court of Aus- tralia, 2001–02. -

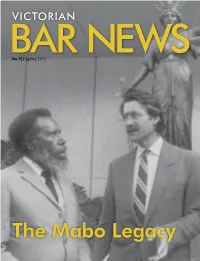

The Mabo Legacy the START of a REWARDING JOURNEY for VICTORIAN BAR MEMBERS

No.152 Spring 2012 ISSN 0159 3285 ISSN The Mabo Legacy THE START OF A REWARDING JOURNEY FOR VICTORIAN BAR MEMBERS. Behind the wheel of a BMW or MINI, what was once a typical commute can be transformed into a satisfying, rewarding journey. With renowned dynamic handling and refined luxurious interiors, it’s little wonder that both BMW and MINI epitomise the ultimate in driving pleasure. The BMW and MINI Corporate Programmes are not simply about making it easier to own some of the world’s safest, most advanced driving machines; they are about enhancing the entire experience of ownership. With a range of special member benefits, they’re our way of ensuring that our corporate customers are given the best BMW and MINI experience possible. BMW Melbourne, in conjunction with BMW Group Australia, is pleased to offer the benefits of the BMW and MINI Corporate Programme to all members of The Victorian Bar, when you purchase a new BMW or MINI. Benefits include: BMW CORPORATE PROGRAMME. MINI CORPORATE PROGRAMME. Complimentary scheduled servicing for Complimentary scheduled servicing for 4 years / 60,000km 4 years / 60,000km Reduced dealer delivery charges Reduced dealer delivery charges Complimentary use of a BMW during scheduled Complimentary valet service servicing* Corporate finance rates to approved customers Door-to-door pick-up during scheduled servicing A dedicated Corporate Sales Manager at your Reduced rate on a BMW Driver Training course local MINI Garage Your spouse is also entitled to enjoy all the benefits of the BMW and MINI Corporate Programme when they purchase a new BMW or MINI. -

Situating Women Judges on the High Court of Australia: Not Just Men in Skirts?

Situating Women Judges on the High Court of Australia: Not Just Men in Skirts? Kcasey McLoughlin BA (Hons) LLB (Hons) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, the University of Newcastle January 2016 Statement of Originality This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. I give consent to the final version of my thesis being made available worldwide when deposited in the University's Digital Repository, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Kcasey McLoughlin ii Acknowledgments I am most grateful to my principal supervisor, Jim Jose, for his unswerving patience, willingness to share his expertise and for the care and respect he has shown for my ideas. His belief in challenging disciplinary boundaries, and seemingly limitless generosity in mentoring others to do so has sustained me and this thesis. I am honoured to have been in receipt of his friendship, and owe him an enormous debt of gratitude for his unstinting support, assistance and encouragement. I am also grateful to my co-supervisor, Katherine Lindsay, for generously sharing her expertise in Constitutional Law and for fostering my interest in the High Court of Australia and the judges who sit on it. Her enthusiasm, very helpful advice and intellectual guidance were instrumental motivators in completing the thesis. The Faculty of Business and Law at the University of Newcastle has provided a supportive, collaborative and intellectual space to share and debate my research. -

Who's That with Abrahams

barTHE JOURNAL OF THE NSWnews BAR ASSOCIATION | SUMMER 2008/09 Who’s that with Abrahams KC? Rediscovering Rhetoric Justice Richard O’Connor rediscovered Bullfry in Shanghai | CONTENTS | 2 President’s column 6 Editor’s note 7 Letters to the editor 8 Opinion Access to court information The costs circus 12 Recent developments 24 Features 75 Legal history The Hon Justice Foster The criminal jurisdiction of the Federal The Kyeema air disaster The Hon Justice Macfarlan Court NSW Law Almanacs online The Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina The Hon Justice Ward Saving St James Church 40 Addresses His Honour Judge Michael King SC Justice Richard Edward O’Connor Rediscovering Rhetoric 104 Personalia The current state of the profession His Honour Judge Storkey VC 106 Obituaries Refl ections on the Federal Court 90 Crossword by Rapunzel Matthew Bracks 55 Practice 91 Retirements 107 Book reviews The Keble Advocacy Course 95 Appointments 113 Muse Before the duty judge in Equity Chief Justice French Calderbank offers The Hon Justice Nye Perram Bullfry in Shanghai Appearing in the Commercial List The Hon Justice Jagot 115 Bar sports barTHE JOURNAL OF THE NSWnews BAR ASSOCIATION | SUMMER 2008-09 Bar News Editorial Committee Cover the New South Wales Bar Andrew Bell SC (editor) Leonard Abrahams KC and Clark Gable. Association. Keith Chapple SC Photo: Courtesy of Anthony Abrahams. Contributions are welcome and Gregory Nell SC should be addressed to the editor, Design and production Arthur Moses SC Andrew Bell SC Jeremy Stoljar SC Weavers Design Group Eleventh Floor Chris O’Donnell www.weavers.com.au Wentworth Chambers Duncan Graham Carol Webster Advertising 180 Phillip Street, Richard Beasley To advertise in Bar News visit Sydney 2000. -

Admission of Lawyers∗

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF NEW SOUTH WALES BANCO COURT ADMISSION OF LAWYERS∗ 1. Now that the formal part of the proceedings has ended, I would like to warmly welcome you to the Supreme Court of New South Wales. Present with me on the Bench today are two other Justices of the Supreme Court. Together, we constitute the Court that has, in exercise of its jurisdiction, admitted you to practice. 2. As we gather here today, I would like to begin by acknowledging the traditional custodians of the land on which we meet, the Gadigal people of the Eora nation, and pay my respects to their Elders, past, present and emerging. We recognise the longstanding and enduring customs and traditions of Australia’s First Nations, and acknowledge with deep regret the role our legal system has had in perpetrating many injustices against Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. 3. To all the new lawyers here today, welcome to the legal profession. Today is a day for celebration. You have all worked extremely hard to get here, through caffeine-fuelled nights and obscure problem questions, reading countless wafer-thin pages of textbook and more cases than you can hope to remember. You have entered the world of eggshell skulls, encountered the mysterious “reasonable person” and have understood that the Constitution consists of so much more than “the vibe of the thing”. 4. In becoming a lawyer, you have today joined a centuries-old profession with ancient origins.1 The custom of advocates swearing an admissions oath ∗ I express my thanks to my Research Director, Ms Rosie Davidson, for her assistance in the preparation of this address. -

The High Court and the Parliament Partners in Law-Making Or Hostile Combatants?*

The High Court and the Parliament Partners in law-making or hostile combatants?* Michael Coper The question of when a human life begins poses definitional and philosophical puzzles that are as familiar as they are unanswerable. It might surprise you to know that the question of when the High Court of Australia came into existence raises some similar puzzles,1 though they are by contrast generally unfamiliar and not quite so difficult to answer. Interestingly, the High Court tangled with this issue in its very first case, a case called Hannah v Dalgarno,2 argued—by Wise3 on one side and Sly4 on the other—on 6 and 10 November 1903, and decided the next day on a date that now positively reverberates with constitutional significance, 11 November.5 * This paper was presented as a lecture in the Department of the Senate Occasional Lecture Series at Parliament House on 19 September 2003. I am indebted to my colleagues Fiona Wheeler and John Seymour for their comments on an earlier draft. 1 See Tony Blackshield and Francesca Dominello, ‘Constitutional basis of Court’ in Tony Blackshield, Michael Coper and George Williams (eds), The Oxford Companion to the High Court of Australia, South Melbourne, Vic., Oxford University Press, 2001 (hereafter ‘The Oxford Companion’): 136. 2 (1903) 1 CLR 1; Francesca Dominello, ‘Hannah v Dalgarno’ in The Oxford Companion: 316. 3 Bernhard Ringrose Wise (1858–1916) was the Attorney-General for NSW and had been a framer of the Australian Constitution. 4 Richard Sly (1849–1929) was one of three lawyer brothers (including George, a founder of the firm of Sly and Russell), who all had doctorates in law. -

Speech Given by Chief Justice Higgins Ceremonial Sitting on the Occasion of the Retirement of Justice Gray Friday 29 July 2011

Speech given by Chief Justice Higgins Ceremonial Sitting on the occasion of the retirement of Justice Gray Friday 29 July 2011 Welcome to everybody who is in attendance today and particularly may I welcome our guest of honour Justice Gray, his wife Laura and the extended Gray family, two generations thereof being present. I welcome the judges who are present today. Particularly we are honoured by the presence of Chief Justice Robert French of the High Court of Australia, former judges of this Court, the Honourable Jeffrey Miles, the Honourable John Gallop and former Master of this Court Alan Hogan. It is a great pleasure to have them with us today along with the Magistrates, Members of the Legislative Assembly, Practitioners, staff members, and of course, ladies and gentlemen. I acknowledge the apologies of those unable to attend this ceremonial sitting; their Honours, Justices of the High Court, otherwise than of course his Honour the Chief Justice, Chief Minister Katy Gallagher, the Federal Attorney General the Honourable Robert McClelland, the Commonwealth Solicitor General Stephen Gageler, Patrick Keane Chief Justice of the Federal Court, Deputy Chief Justice John Faulks and her Honour Justice Mary Finn of the Family Court, former judge of this court the Honourable Dr Ken Crispin who offers the inadequate excuse that he is sojourning in the south of France, and the further additional and recent acting judges of this court. Before I begin, I wish to acknowledge the traditional owners of the land the Ngunnawal people before I mention his Honour, Justice Gray, who joined the 1 ranks of this court on 12 October 2000 from South Australia, and was later appointed President of the ACT Court of Appeal on 21 December 2007, following the retirement of Justice Ken Crispin. -

THE UNIVERSITY of WESTERN AUSTRALIA LAW REVIEW Volume 42(1) May 2017

THE UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA LAW REVIEW Volume 42(1) May 2017 Articles Ministerial Advisers and the Australian Constitution Yee‐Fui Ng .............................................................................................................. 1 All-Embracing Approaches to Constitutional Interpretation & ‘Moderate Originalism’ Stephen Puttick ........................................................................................................ 30 A Proportionate Burden: Revisiting the Constitutionality of Optional Preferential Voting Eric Chan ................................................................................................................ 57 London & New Mashonaland Exploration Co Ltd v New Mashonaland Exploration Co Ltd: Is It Authority That Directors Can Compete with the Company? Dominique Le Miere ............................................................................................... 98 Claims Relating to Possession of a Ship: Wilmington Trust Company (Trustee) v The Ship “Houston” [2016] FCA 1349 Mohammud Jaamae Hafeez‐Baig and Jordan English ......................................... 128 Intimidation, Consent and the Role of Holistic Judgments in Australian Rape Law Jonathan Crowe and Lara Sveinsson..................................................................... 136 Young Offenders Act 1984 (WA), Section 126 Special Orders: Extra Punitive Sentencing Legislation for Juveniles’ Craig Astill and William Yoo .......................................................................... 155 From Down -

TWENTY-SIXTH ANNUAL REPORT 2001 - 2002 Contacting the Administrative Review Council

ADMINISTRATIVE REVIEW COUNCIL TWENTY-SIXTH ANNUAL REPORT 2001 - 2002 Contacting the Administrative Review Council For information about this report, or more generally about the Council’s work, please contact: The Executive Director Administrative Review Council Robert Garran Offices National Circuit BARTON ACT 2600 Telephone: (02) 6250 5800 Facsimile: (02) 6250 5980 e-mail: [email protected] Internet: law.gov.au/arc The offices of the Administrative Review Council are located in the Robert Garran Offices, National Circuit, Barton ACT. © Commonwealth of Australia 2002 ISBN 0 642 21070 5 This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. ii ADMINISTRATIVE REVIEW COUNCIL 29 October 2002 The Hon Daryl Williams AM QC MP Attorney-General Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Dear Attorney-General In accordance with section 58 of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal Act 1975, I am pleased to present you with this report on the operation of the Administrative Review Council for the year 2001-2002. Yours sincerely Wayne Martin QC President Wayne Martin QC Justice Garry Downes AM Ron McLeod AM Professor David Weisbrot Bill Blick PSM Christine Charles Robert Cornall Professor Robin Creyke Stephen Gageler SC Patricia Ridley Robert Garran Offices, National Circuit, Barton ACT 2600 Telephone: (02) 6250 5800 Facsimile: (02) 6250 5980 e-mail: [email protected] Internet: law.gov.au/arc iii Photograph of the Council at 28 June 2002. Those photographed are: Standing: Stephen Gageler SC, Ron McLeod AM, Bill Blick PSM, Justice Garry Downes AM. -

I I I I I I I I 1

Bench and Bar Dinner - May 1995 I I I I I iflV1.- '. - --- I Sir Anthony addresses the (Ito r) Susan Crennan QC, President of the Australian Bar Association, assembled masses. Chief Justice Gleeson AC, Murray Tobias QC. I May Further, the definition of merit is critically dependent on one's May was a busy month. On 8 May the Honourable Justice perception of what makes a good judge: most lawyers would G.F. Fitzgerald, AC, Chief Justice of Queensland, gave a agree that it is necessary for a judge to understand the overall graduation speech in which he remarked on the process of structure of the common law, know or be able to ascertain judicial selection: and comprehend the detailed rules formulated by other judges, "Both the judicial responsibility to produce a unique Australian and reason by processes of inductive and deductive logic to jurisprudence and the values and policy choices involved in conclusions suitable for the decision of particular disputes, judicial decisions draw attention to the narrow social group such a course exposes a judicial decision-maker to the n from which judges-especially High Court and other appellate experience and wisdom manifest in prior decisions, and many judges - are drawn. While judges represent the community consider that that exhausts the judicial function. Others, as a whole, and do not, and should not, represent any section myself included, consider that such an approach also of the community, it is a legitimate criticism that the judiciary perpetuates any errors, injustices or conflicts with modem is drawn from an extremely narrow group and hence its Australian values which prior decisions involve, and that it is I opinions and perspectives on contemporary community values essential to constantly test current principles against the ideal and attitudes are distorted and limited.