Post-Separation Conflict and the Use of Family Violence Orders

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Expert Determination Mchugh April 2007

Expert Determination’ By The Hon. Michael McHugh AC2 As a number of recent court judgments have noted, Expert Determinations have become a popular method for determining disputes. In an expert determination, the decision maker decides an issue as an expert and not as an arbitrator. As Einstein J noted in The Heart Research Institute Limited v Psiron Limited [2002] NSWC 646: “In practice, Expert Determination is a process where an independent Expert decides an issue or issues between the parties. The disputants agree beforehand whether or not they wilt be bound by the decisions of the Expert. Expert Determination provides an informal, speedy and effective way of resolving disputes, particularly disputes which are of a specific technical character or specialised kind. .Unlike arbitration, Expert Determination is not governed by legislation, the adoption of Expert Determination is a consensual process by which the parties agree to take defined steps in resolving disputes.. .Expert Determination clauses have become commonplace, particularly in the construction industry, and frequently incorporate terms by reference to standards such as the rules laid down by the Institute ofArbitrators and Mediators ofAustralia, the Institute of Engineers Australia or model agreements such as that proposed by Sir Laurence Street in 1992. Although the precise terms of these rules and guidelines may vary, they have in common that they provide a contractual process by which Expert Determination is conducted.” More and more, disputants and their advisers prefer -

Fact and Law Stephen Gageler

Fact and Law Stephen Gageler* I The essential elements of the decision-making process of a court are well understood and can be simply stated. The court finds the facts. The court ascertains the law. The court applies the law to the facts to decide the case. The distinction between finding the facts and ascertaining the law corresponds to the distinction in a common law court between the traditional roles of jury and judge. The court - traditionally the jury - finds the facts on the basis of evidence. The court - always the judge - ascertains the law with the benefit of argument. Ascertaining the law is a process of induction from one, or a combination, of two sources: the constitutional or statutory text and the previously decided cases. That distinction between finding the facts and ascertaining the law, together with that description of the process of ascertaining the law, works well enough for most purposes in most cases. * Solicitor-General of Australia. This paper was presented as the Sir N inian Stephen Lecture at the University of Newcastle on 14 August 2009. The Sir Ninian Stephen Lecture was established to mark the arrival of the first group of Bachelor of Laws students at the University of Newcastle in 1993. It is an annual event that is delivered by an eminent lawyer every academic year. 1 STEPHEN GAGELER (2008-9) But it can become blurred where the law to be ascertained is not clear or is not immutable. The principles of interpretation or precedent that govern the process of induction may in some courts and in some cases leave room for choice as to the meaning to be inferred from the constitutional or statutory text or as to the rule to be drawn from the previously decided cases. -

Standing Committee on Law and Justice

REPORT ON PROCEEDINGS BEFORE STANDING COMMITTEE ON LAW AND JUSTICE CRIMES (APPEAL AND REVIEW) AMENDMENT (DOUBLE JEOPARDY) BILL 2019 CORRECTED At Macquarie Room, Parliament House, Sydney, on Wednesday 24 July 2019 The Committee met at 9:15 PRESENT The Hon. Niall Blair (Chair) The Hon. Anthony D'Adam The Hon. Greg Donnelly (Deputy Chair) The Hon. Wes Fang The Hon. Rod Roberts Mr David Shoebridge The Hon. Natalie Ward Wednesday, 24 July 2019 Legislative Council Page 1 The CHAIR: Good morning and welcome to the hearing of the Law and Justice Committee inquiry into the Crimes (Appeal and Review) Amendment (Double Jeopardy) Bill 2019. Before I commence I would like to acknowledge the Gadigal people, who are the traditional custodians of this land. I would also like to pay respect to the elders past and present of the Eora nation and extend that respect to other Aboriginal people present today. The Committee's task in conducting the inquiry is to examine the technical legal implications of the bill's proposed amendments to the current law in respect of double jeopardy. The bill is a private member's bill introduced to Parliament by Mr David Shoebridge in May this year, then referred by the Legislative Council to this Committee for us to examine and then to report back to the Legislative Council with recommendations for the New South Wales Government. At this stage the Committee expects to provide its report by the end of August. Today is the only hearing we plan to hold for this inquiry, although the Committee has met informally with members of the families of Colleen Walker-Craig, Evelyn Greenup and Clinton Speedy-Duroux in Bowraville. -

Ceremonial Sitting of the Tribunal for the Swearing in and Welcome of the Honourable Justice Kerr As President

AUSCRIPT AUSTRALASIA PTY LIMITED ABN 72 110 028 825 Level 22, 179 Turbot Street, Brisbane QLD 4000 PO Box 13038 George St Post Shop, Brisbane QLD 4003 T: 1800 AUSCRIPT (1800 287 274) F: 1300 739 037 E: [email protected] W: www.auscript.com.au TRANSCRIPT OF PROCEEDINGS O/N H-59979 ADMINISTRATIVE APPEALS TRIBUNAL CEREMONIAL SITTING OF THE TRIBUNAL FOR THE SWEARING IN AND WELCOME OF THE HONOURABLE JUSTICE KERR AS PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE JUSTICE KERR, President THE HONOURABLE JUSTICE KEANE, Chief Justice of the Federal Court of Australia THE HONOURABLE JUSTICE BUCHANAN, Presidential Member DEPUTY PRESIDENT S.D. HOTOP DEPUTY PRESIDENT R.P. HANDLEY DEPUTY PRESIDENT D.G. JARVIS THE HONOURABLE R.J. GROOM, Deputy President DEPUTY PRESIDENT P.E. HACK SC DEPUTY PRESIDENT J.W. CONSTANCE THE HONOURABLE B.J.M. TAMBERLIN QC, Deputy President DEPUTY PRESIDENT S.E. FROST DEPUTY PRESIDENT R. DEUTSCH PROF R.M. CREYKE, Senior Member MS G. ETTINGER, Senior Member MR P.W. TAYLOR SC, Senior Member MS J.F. TOOHEY, Senior Member MS A.K. BRITTON, Senior Member MR D. LETCHER SC, Senior Member MS J.L REDFERN PSM, Senior Member MS G. LAZANAS, Senior Member DR I.S. ALEXANDER, Member DR T.M. NICOLETTI, Member DR H. HAIKAL-MUKHTAR, Member DR M. COUCH, Member SYDNEY 9.32 AM, WEDNESDAY, 16 MAY 2012 .KERR 16.5.12 P-1 ©Commonwealth of Australia KERR J: Chief Justice, I have the honour to announce that I have received a commission from her Excellency, the Governor General, appointing me as President of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal. -

Review Essay Open Chambers: High Court Associates and Supreme Court Clerks Compared

REVIEW ESSAY OPEN CHAMBERS: HIGH COURT ASSOCIATES AND SUPREME COURT CLERKS COMPARED KATHARINE G YOUNG∗ Sorcerers’ Apprentices: 100 Years of Law Clerks at the United States Supreme Court by Artemus Ward and David L Weiden (New York: New York University Press, 2006) pages i–xiv, 1–358. Price A$65.00 (hardcover). ISBN 0 8147 9404 1. I They have been variously described as ‘junior justices’, ‘para-judges’, ‘pup- peteers’, ‘courtiers’, ‘ghost-writers’, ‘knuckleheads’ and ‘little beasts’. In a recent study of the role of law clerks in the United States Supreme Court, political scientists Artemus Ward and David L Weiden settle on a new metaphor. In Sorcerers’ Apprentices: 100 Years of Law Clerks at the United States Supreme Court, the authors borrow from Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s famous poem to describe the transformation of the institution of the law clerk over the course of a century, from benign pupilage to ‘a permanent bureaucracy of influential legal decision-makers’.1 The rise of the institution has in turn transformed the Court itself. Nonetheless, despite the extravagant metaphor, the authors do not set out to provide a new exposé on the internal politics of the Supreme Court or to unveil the clerks (or their justices) as errant magicians.2 Unlike Bob Woodward and Scott Armstrong’s The Brethren3 and Edward Lazarus’ Closed Chambers,4 Sorcerers’ Apprentices is not pitched to the public’s right to know (or its desire ∗ BA, LLB (Hons) (Melb), LLM Program (Harv); SJD Candidate and Clark Byse Teaching Fellow, Harvard Law School; Associate to Justice Michael Kirby AC CMG, High Court of Aus- tralia, 2001–02. -

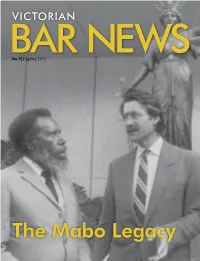

The Mabo Legacy the START of a REWARDING JOURNEY for VICTORIAN BAR MEMBERS

No.152 Spring 2012 ISSN 0159 3285 ISSN The Mabo Legacy THE START OF A REWARDING JOURNEY FOR VICTORIAN BAR MEMBERS. Behind the wheel of a BMW or MINI, what was once a typical commute can be transformed into a satisfying, rewarding journey. With renowned dynamic handling and refined luxurious interiors, it’s little wonder that both BMW and MINI epitomise the ultimate in driving pleasure. The BMW and MINI Corporate Programmes are not simply about making it easier to own some of the world’s safest, most advanced driving machines; they are about enhancing the entire experience of ownership. With a range of special member benefits, they’re our way of ensuring that our corporate customers are given the best BMW and MINI experience possible. BMW Melbourne, in conjunction with BMW Group Australia, is pleased to offer the benefits of the BMW and MINI Corporate Programme to all members of The Victorian Bar, when you purchase a new BMW or MINI. Benefits include: BMW CORPORATE PROGRAMME. MINI CORPORATE PROGRAMME. Complimentary scheduled servicing for Complimentary scheduled servicing for 4 years / 60,000km 4 years / 60,000km Reduced dealer delivery charges Reduced dealer delivery charges Complimentary use of a BMW during scheduled Complimentary valet service servicing* Corporate finance rates to approved customers Door-to-door pick-up during scheduled servicing A dedicated Corporate Sales Manager at your Reduced rate on a BMW Driver Training course local MINI Garage Your spouse is also entitled to enjoy all the benefits of the BMW and MINI Corporate Programme when they purchase a new BMW or MINI. -

“Women's Voices in Ancient and Modern Times”

“Women’s Voices in Ancient and Modern Times” Speech delivered at the ANU Law Students’ Society Women in Law Breakfast 22 March 2021 I acknowledge the traditional custodians of this land and pay my respects to their elders— past, present, and emerging. I acknowledge that sovereignty over this land was never ceded. I extend my respects to all First Nations people who may be present today. I acknowledge that, in Australia over the last 30 years, at least 442 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have died in custody. It is a pleasure to be speaking to a room of young women who will be part of the next generation of Australian and international lawyers. I hope that we will also see you in politics. In my youth, a very long time ago, the aspirational statement was “a woman’s place is in the House—and in the Senate”. As recent events show, that sentiment remains aspirational today. Women’s voices are still being devalued. Today, I will speak about the voices of women in ancient and modern democracies. Women in Ancient Greece Since ancient times, women’s voices have been silenced. While we could all name outstanding male Ancient Greek philosophers, poets, politicians, and physicians, how many of us know of eminent women from that time? The few women’s voices of which we do know are those of mythical figures. In Ancient Greece, the gods and goddesses walked among the populace, and people were ever mindful of their presence. They exerted a powerful influence. Who were the goddesses? Athena was a warrior, a judge, and a giver of wisdom, but she was born full-grown from her father (she had no mother) and she remained virginal. -

5281 Bar News Winter 07.Indd

Mediation and the Bar Some perspectives on US litigation Theories of constitutional interpretation: a taxonomy CONTENTS 2 Editor’s note 3 President’s column 5 Opinion The central role of the jury 7 Recent developments 12 Address 2007 Sir Maurice Byers Lecture 34 Features: Mediation and the Bar Effective representation at mediation Should the New South Wales Bar remain agnostic to mediation? Constructive mediation A mediation miscellany 66 Readers 01/2007 82 Obituaries Nicholas Gye 44 Practice 67 Muse Daniel Edmund Horton QC Observations on a fused profession: the Herbert Smith Advocacy Unit A paler shade of white Russell Francis Wilkins Some perspectives on US litigation Max Beerbohm’s Dulcedo Judiciorum 88 Bullfry Anything to disclose? 72 Personalia 90 Books 56 Legal history The Hon Justice Kenneth Handley AO Interpreting Statutes Supreme Court judges of the 1940s The Hon Justice John Bryson Principles of Federal Criminal Law State Constitutional Landmarks 62 Bar Art 77 Appointments The Hon Justice Ian Harrison 94 Bar sports 63 Great Bar Boat Race The Hon Justice Elizabeth Fullerton NSW v Queensland Bar Recent District Court appointments The Hon Justice David Hammerschlag 64 Bench and Bar Dinner 96 Coombs on Cuisine barTHE JOURNAL OF THEnews NSW BAR ASSOCIATION | WINTER 2007 Bar News Editorial Committee Design and production Contributions are welcome and Andrew Bell SC (editor) Weavers Design Group should be addressed to the editor, Keith Chapple SC www.weavers.com.au Andrew Bell SC Eleventh Floor Gregory Nell SC Advertising John Mancy Wentworth Selborne Chambers To advertise in Bar News visit Arthur Moses 180 Phillip Street, www.weavers.com.au/barnews Chris O’Donnell Sydney 2000. -

![[1989] Reform 48 with Maori Needs](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6517/1989-reform-48-with-maori-needs-616517.webp)

[1989] Reform 48 with Maori Needs

[1989] Reform 48 with Maori needs. (NZH, 30 November * * * 1988) The most controversial recommendation, personalia according to the NZH (30 November 1988) is: Sir Ronald Wilson its advocacy of more culturally based rem Sir Ronald Wilson will retire from the edies. It pushes for a centre of cultural re High Court with effect from 13 February search and various tribal organisations 1989. Sir Ronald was appointed to the High which could increase acknowledgement of Court on 21 May 1979 as the first Justice of the relevance of Maori values and make the court to be appointed from Western Aus culturally based penalties for Maori of tralia. Prior to his appointment Sir Ronald fenders effective’. had been Solicitor-General of Western Aus essays on legislative drafting. The Adel tralia. It is understood that he will now de aide Law Review Association at the Univer vote his energies to his other roles as Pres sity of Adelaide Law School has published a ident of the Uniting Church in Australia and book in honour of Mr JQ Ewens, CMG, Chancellor of Murdoch University. CBE, QC, the former First Parliamentary The Hon Justice Michael McHugh Counsel of the Commonwealth. The book, entitled Essays on Legislative Drafting, is Justice McHugh will fill the vacancy on edited by the Chairman of the Law Reform the High Court created by the resignation of Commission of Victoria, Mr David St L Kel Justice Wilson. His appointment will take ef ly. John Ewens, now 81, has also been ad fect from 14 February 1989. Justice McHugh, visor to the Woodhouse Inquiry into Nation formerly of the New South Wales Court of al Rehabilitation and Compensation, drafts Appeal and Supreme Court, was elevated to man and advisor to the Norfolk Island Ad the Bench in 1984. -

Situating Women Judges on the High Court of Australia: Not Just Men in Skirts?

Situating Women Judges on the High Court of Australia: Not Just Men in Skirts? Kcasey McLoughlin BA (Hons) LLB (Hons) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, the University of Newcastle January 2016 Statement of Originality This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. I give consent to the final version of my thesis being made available worldwide when deposited in the University's Digital Repository, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Kcasey McLoughlin ii Acknowledgments I am most grateful to my principal supervisor, Jim Jose, for his unswerving patience, willingness to share his expertise and for the care and respect he has shown for my ideas. His belief in challenging disciplinary boundaries, and seemingly limitless generosity in mentoring others to do so has sustained me and this thesis. I am honoured to have been in receipt of his friendship, and owe him an enormous debt of gratitude for his unstinting support, assistance and encouragement. I am also grateful to my co-supervisor, Katherine Lindsay, for generously sharing her expertise in Constitutional Law and for fostering my interest in the High Court of Australia and the judges who sit on it. Her enthusiasm, very helpful advice and intellectual guidance were instrumental motivators in completing the thesis. The Faculty of Business and Law at the University of Newcastle has provided a supportive, collaborative and intellectual space to share and debate my research. -

Process, but Also Assumes a Role in the Administration of the Court

Mason process, but also assumes a role in the administration of the Court. Frank Jones Mason, Anthony Frank (b 21 April 1925; Justice 1972–87; Chief Justice 1987–95) was a member of the High Court for 23 years and is regarded by many as one of Australia’s great- est judges, as important and influential as Dixon.The ninth Chief Justice,he presided over a period ofsignificant change in the Australian legal system, his eight years as Chief Justice having been described as among the most exciting and important in the Court’s history. Mason grew up in Sydney, where he attended Sydney Grammar School. His father was a surveyor who urged him to follow in his footsteps; however, Mason preferred to follow in the footsteps of his uncle, a prominent Sydney KC. After serving with the RAAF as a flying officer from 1944 to 1945, he enrolled at the University of Sydney, graduating with first-class honours in both law and arts. Mason was then articled with Clayton Utz & Co in Sydney, where he met his wife Patricia, with whom he has two sons. He also served as an associate to Justice David Roper of the Supreme Court of NSW. He moved to the Sydney Bar in 1951, where he was an unqualified success, becoming one of Barwick’s favourite junior counsel. Mason’s practice was primarily in equity and commercial law,but he also took on a number ofconstitutional and appellate cases. After only three years at the Bar, he appeared before the High Court in R v Davison (1954), in which he successfully persuaded the Bench that certain sections of the Bankruptcy Act 1924 (Cth) invalidly purported to confer Anthony Mason, Justice 1972–87, Chief Justice 1987–95 in judicial power upon a registrar of the Bankruptcy Court. -

Who's That with Abrahams

barTHE JOURNAL OF THE NSWnews BAR ASSOCIATION | SUMMER 2008/09 Who’s that with Abrahams KC? Rediscovering Rhetoric Justice Richard O’Connor rediscovered Bullfry in Shanghai | CONTENTS | 2 President’s column 6 Editor’s note 7 Letters to the editor 8 Opinion Access to court information The costs circus 12 Recent developments 24 Features 75 Legal history The Hon Justice Foster The criminal jurisdiction of the Federal The Kyeema air disaster The Hon Justice Macfarlan Court NSW Law Almanacs online The Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina The Hon Justice Ward Saving St James Church 40 Addresses His Honour Judge Michael King SC Justice Richard Edward O’Connor Rediscovering Rhetoric 104 Personalia The current state of the profession His Honour Judge Storkey VC 106 Obituaries Refl ections on the Federal Court 90 Crossword by Rapunzel Matthew Bracks 55 Practice 91 Retirements 107 Book reviews The Keble Advocacy Course 95 Appointments 113 Muse Before the duty judge in Equity Chief Justice French Calderbank offers The Hon Justice Nye Perram Bullfry in Shanghai Appearing in the Commercial List The Hon Justice Jagot 115 Bar sports barTHE JOURNAL OF THE NSWnews BAR ASSOCIATION | SUMMER 2008-09 Bar News Editorial Committee Cover the New South Wales Bar Andrew Bell SC (editor) Leonard Abrahams KC and Clark Gable. Association. Keith Chapple SC Photo: Courtesy of Anthony Abrahams. Contributions are welcome and Gregory Nell SC should be addressed to the editor, Design and production Arthur Moses SC Andrew Bell SC Jeremy Stoljar SC Weavers Design Group Eleventh Floor Chris O’Donnell www.weavers.com.au Wentworth Chambers Duncan Graham Carol Webster Advertising 180 Phillip Street, Richard Beasley To advertise in Bar News visit Sydney 2000.