Evidence and Truth* the Honourable Justice Stephen Gageler AC†

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Tasmanian ABC Production Unit Is an Invaluable Part of Media in Tasmania

The Tasmanian ABC Production Unit is an invaluable part of media in Tasmania. The following is an excerpt of the ABC Strategic Plan pertinent to the issue: ABC STRATEGIC PLAN 2010–13 page 9 Providing content and services of the highest quality lies at the heart of the ABC’s public purpose. Audiences expect the Corporation to offer experiences that are engaging, entertaining, informative and trustworthy; the ABC will meet these expectations. In particular, it remains committed to the creation and delivery of Australian content, services to local communities, the highest levels of editorial standards and multi-platform delivery of content. The Corporation’s ability to sustain and transform itself depends fundamentally on its processes and people. As a public service, it must constantly seek to maximise the efficiency and effectiveness of its operations, converting savings into its programs and services. At the same time, it is crucial that the ABC maintain and support a creative and adaptable workforce that is capable of meeting the demands of the future, and actively engage with the wider Australian creative community. The Production Unit in Tasmania fulfils all these criteria. Creation of local content that tells the unique stories of Tasmania. These stories can be made without the need to seek development funding. The ABC Production Unit is a highly qualified and experienced team – able to create quality content in a timely way that matches or betters private production. The ABC has long been an employer of emerging media people both in front of camera and in production. Camera/sound/editing. This is invaluable to support of media community in Tasmania. -

The Epistemology of Evidence in Cognitive Neuroscience1

To appear in In R. Skipper Jr., C. Allen, R. A. Ankeny, C. F. Craver, L. Darden, G. Mikkelson, and R. Richardson (eds.), Philosophy and the Life Sciences: A Reader. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. The Epistemology of Evidence in Cognitive Neuroscience1 William Bechtel Department of Philosophy and Science Studies University of California, San Diego 1. The Epistemology of Evidence It is no secret that scientists argue. They argue about theories. But even more, they argue about the evidence for theories. Is the evidence itself trustworthy? This is a bit surprising from the perspective of traditional empiricist accounts of scientific methodology according to which the evidence for scientific theories stems from observation, especially observation with the naked eye. These accounts portray the testing of scientific theories as a matter of comparing the predictions of the theory with the data generated by these observations, which are taken to provide an objective link to reality. One lesson philosophers of science have learned in the last 40 years is that even observation with the naked eye is not as epistemically straightforward as was once assumed. What one is able to see depends upon one’s training: a novice looking through a microscope may fail to recognize the neuron and its processes (Hanson, 1958; Kuhn, 1962/1970).2 But a second lesson is only beginning to be appreciated: evidence in science is often not procured through simple observations with the naked eye, but observations mediated by complex instruments and sophisticated research techniques. What is most important, epistemically, about these techniques is that they often radically alter the phenomena under investigation. -

Fact and Law Stephen Gageler

Fact and Law Stephen Gageler* I The essential elements of the decision-making process of a court are well understood and can be simply stated. The court finds the facts. The court ascertains the law. The court applies the law to the facts to decide the case. The distinction between finding the facts and ascertaining the law corresponds to the distinction in a common law court between the traditional roles of jury and judge. The court - traditionally the jury - finds the facts on the basis of evidence. The court - always the judge - ascertains the law with the benefit of argument. Ascertaining the law is a process of induction from one, or a combination, of two sources: the constitutional or statutory text and the previously decided cases. That distinction between finding the facts and ascertaining the law, together with that description of the process of ascertaining the law, works well enough for most purposes in most cases. * Solicitor-General of Australia. This paper was presented as the Sir N inian Stephen Lecture at the University of Newcastle on 14 August 2009. The Sir Ninian Stephen Lecture was established to mark the arrival of the first group of Bachelor of Laws students at the University of Newcastle in 1993. It is an annual event that is delivered by an eminent lawyer every academic year. 1 STEPHEN GAGELER (2008-9) But it can become blurred where the law to be ascertained is not clear or is not immutable. The principles of interpretation or precedent that govern the process of induction may in some courts and in some cases leave room for choice as to the meaning to be inferred from the constitutional or statutory text or as to the rule to be drawn from the previously decided cases. -

Ceremonial Sitting of the Tribunal for the Swearing in and Welcome of the Honourable Justice Kerr As President

AUSCRIPT AUSTRALASIA PTY LIMITED ABN 72 110 028 825 Level 22, 179 Turbot Street, Brisbane QLD 4000 PO Box 13038 George St Post Shop, Brisbane QLD 4003 T: 1800 AUSCRIPT (1800 287 274) F: 1300 739 037 E: [email protected] W: www.auscript.com.au TRANSCRIPT OF PROCEEDINGS O/N H-59979 ADMINISTRATIVE APPEALS TRIBUNAL CEREMONIAL SITTING OF THE TRIBUNAL FOR THE SWEARING IN AND WELCOME OF THE HONOURABLE JUSTICE KERR AS PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE JUSTICE KERR, President THE HONOURABLE JUSTICE KEANE, Chief Justice of the Federal Court of Australia THE HONOURABLE JUSTICE BUCHANAN, Presidential Member DEPUTY PRESIDENT S.D. HOTOP DEPUTY PRESIDENT R.P. HANDLEY DEPUTY PRESIDENT D.G. JARVIS THE HONOURABLE R.J. GROOM, Deputy President DEPUTY PRESIDENT P.E. HACK SC DEPUTY PRESIDENT J.W. CONSTANCE THE HONOURABLE B.J.M. TAMBERLIN QC, Deputy President DEPUTY PRESIDENT S.E. FROST DEPUTY PRESIDENT R. DEUTSCH PROF R.M. CREYKE, Senior Member MS G. ETTINGER, Senior Member MR P.W. TAYLOR SC, Senior Member MS J.F. TOOHEY, Senior Member MS A.K. BRITTON, Senior Member MR D. LETCHER SC, Senior Member MS J.L REDFERN PSM, Senior Member MS G. LAZANAS, Senior Member DR I.S. ALEXANDER, Member DR T.M. NICOLETTI, Member DR H. HAIKAL-MUKHTAR, Member DR M. COUCH, Member SYDNEY 9.32 AM, WEDNESDAY, 16 MAY 2012 .KERR 16.5.12 P-1 ©Commonwealth of Australia KERR J: Chief Justice, I have the honour to announce that I have received a commission from her Excellency, the Governor General, appointing me as President of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal. -

Review Essay Open Chambers: High Court Associates and Supreme Court Clerks Compared

REVIEW ESSAY OPEN CHAMBERS: HIGH COURT ASSOCIATES AND SUPREME COURT CLERKS COMPARED KATHARINE G YOUNG∗ Sorcerers’ Apprentices: 100 Years of Law Clerks at the United States Supreme Court by Artemus Ward and David L Weiden (New York: New York University Press, 2006) pages i–xiv, 1–358. Price A$65.00 (hardcover). ISBN 0 8147 9404 1. I They have been variously described as ‘junior justices’, ‘para-judges’, ‘pup- peteers’, ‘courtiers’, ‘ghost-writers’, ‘knuckleheads’ and ‘little beasts’. In a recent study of the role of law clerks in the United States Supreme Court, political scientists Artemus Ward and David L Weiden settle on a new metaphor. In Sorcerers’ Apprentices: 100 Years of Law Clerks at the United States Supreme Court, the authors borrow from Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s famous poem to describe the transformation of the institution of the law clerk over the course of a century, from benign pupilage to ‘a permanent bureaucracy of influential legal decision-makers’.1 The rise of the institution has in turn transformed the Court itself. Nonetheless, despite the extravagant metaphor, the authors do not set out to provide a new exposé on the internal politics of the Supreme Court or to unveil the clerks (or their justices) as errant magicians.2 Unlike Bob Woodward and Scott Armstrong’s The Brethren3 and Edward Lazarus’ Closed Chambers,4 Sorcerers’ Apprentices is not pitched to the public’s right to know (or its desire ∗ BA, LLB (Hons) (Melb), LLM Program (Harv); SJD Candidate and Clark Byse Teaching Fellow, Harvard Law School; Associate to Justice Michael Kirby AC CMG, High Court of Aus- tralia, 2001–02. -

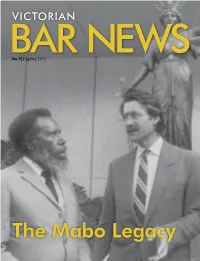

The Mabo Legacy the START of a REWARDING JOURNEY for VICTORIAN BAR MEMBERS

No.152 Spring 2012 ISSN 0159 3285 ISSN The Mabo Legacy THE START OF A REWARDING JOURNEY FOR VICTORIAN BAR MEMBERS. Behind the wheel of a BMW or MINI, what was once a typical commute can be transformed into a satisfying, rewarding journey. With renowned dynamic handling and refined luxurious interiors, it’s little wonder that both BMW and MINI epitomise the ultimate in driving pleasure. The BMW and MINI Corporate Programmes are not simply about making it easier to own some of the world’s safest, most advanced driving machines; they are about enhancing the entire experience of ownership. With a range of special member benefits, they’re our way of ensuring that our corporate customers are given the best BMW and MINI experience possible. BMW Melbourne, in conjunction with BMW Group Australia, is pleased to offer the benefits of the BMW and MINI Corporate Programme to all members of The Victorian Bar, when you purchase a new BMW or MINI. Benefits include: BMW CORPORATE PROGRAMME. MINI CORPORATE PROGRAMME. Complimentary scheduled servicing for Complimentary scheduled servicing for 4 years / 60,000km 4 years / 60,000km Reduced dealer delivery charges Reduced dealer delivery charges Complimentary use of a BMW during scheduled Complimentary valet service servicing* Corporate finance rates to approved customers Door-to-door pick-up during scheduled servicing A dedicated Corporate Sales Manager at your Reduced rate on a BMW Driver Training course local MINI Garage Your spouse is also entitled to enjoy all the benefits of the BMW and MINI Corporate Programme when they purchase a new BMW or MINI. -

Annual Report 2016–2017 National Library of Australia Annual Report 2016–2017

ANNUAL REPORT 2016–2017 REPORT ANNUAL NATIONAL LIBRARY OF AUSTRALIA OF AUSTRALIA LIBRARY NATIONAL ANNUAL REPORT 2016–2017 NATIONAL LIBRARY OF AUSTRALIA ANNUAL REPORT 2016–2017 NATIONAL LIBRARY OF AUSTRALIA NATIONAL LIBRARY OF AUSTRALIA 4 August 2017 Senator the Hon. Mitch Fifield Minister for the Arts Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Dear Minister National Library of Australia Annual Report 2016–2017 The Council, as the accountable authority of the National Library of Australia, has pleasure in submitting to you for presentation to each House of Parliament its annual report covering the period 1 July 2016 to 30 June 2017. Published by the National Library of Australia The Council approved this report at its meeting in Canberra on 4 August 2017. Parkes Place Canberra ACT 2600 The report is submitted to you in accordance with section 46 of the Public T 02 6262 1111 Governance and Performance and Accountability Act 2013. F 02 6257 1703 National Relay Service 133 677 We commend the Annual Report to you. nla.gov.au/policy/annual.html Yours sincerely ABN 28 346 858 075 © National Library of Australia 2017 ISSN 0313-1971 (print) 1443-2269 (online) National Library of Australia Mr Ryan Stokes Dr Marie-Louise Ayres Annual report / National Library of Australia.–8th (1967/68)– Chair of Council Director-General Canberra: NLA, 1968––v.; 25 cm. Annual. Continues: National Library of Australia. Council. Annual report of the Council = ISSN 0069-0082. Report year ends 30 June. ISSN 0313-1971 = Annual report–National Library of Australia. 1. National Library of Australia–Periodicals. 027.594 Canberra ACT 2600 Prepared by the Executive and Public Programs Division T +61 2 6262 1111 F +61 2 6257 1703 Printed by Union Offset Hearing or speech impaired-call us via the National Relay Service on 133 677 nla.gov.au ABN 28 346 858 075 Cover image: M.H. -

Situating Women Judges on the High Court of Australia: Not Just Men in Skirts?

Situating Women Judges on the High Court of Australia: Not Just Men in Skirts? Kcasey McLoughlin BA (Hons) LLB (Hons) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, the University of Newcastle January 2016 Statement of Originality This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. I give consent to the final version of my thesis being made available worldwide when deposited in the University's Digital Repository, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Kcasey McLoughlin ii Acknowledgments I am most grateful to my principal supervisor, Jim Jose, for his unswerving patience, willingness to share his expertise and for the care and respect he has shown for my ideas. His belief in challenging disciplinary boundaries, and seemingly limitless generosity in mentoring others to do so has sustained me and this thesis. I am honoured to have been in receipt of his friendship, and owe him an enormous debt of gratitude for his unstinting support, assistance and encouragement. I am also grateful to my co-supervisor, Katherine Lindsay, for generously sharing her expertise in Constitutional Law and for fostering my interest in the High Court of Australia and the judges who sit on it. Her enthusiasm, very helpful advice and intellectual guidance were instrumental motivators in completing the thesis. The Faculty of Business and Law at the University of Newcastle has provided a supportive, collaborative and intellectual space to share and debate my research. -

Analysis - Identify Assumptions, Reasons and Claims, and Examine How They Interact in the Formation of Arguments

Analysis - identify assumptions, reasons and claims, and examine how they interact in the formation of arguments. Individuals use analytics to gather information from charts, graphs, diagrams, spoken language and documents. People with strong analytical skills attend to patterns and to details. They identify the elements of a situation and determine how those parts interact. Strong interpretations skills can support high quality analysis by providing insights into the significance of what a person is saying or what something means. Inference - draw conclusions from reasons and evidence. Inference is used when someone offers thoughtful suggestions and hypothesis. Inference skills indicate the necessary or the very probable consequences of a given set of facts and conditions. Conclusions, hypotheses, recommendations or decisions that are based on faulty analysis, misinformation, bad data or biased evaluations can turn out to be mistaken, even if they have reached using excellent inference skills. Evaluative - assess the credibility of sources of information and the claims they make, and determine the strength and weakness or arguments. Applying evaluation skills can judge the quality of analysis, interpretations, explanations, inferences, options, opinions, beliefs, ideas, proposals, and decisions. Strong explanation skills can support high quality evaluation by providing evidence, reasons, methods, criteria, or assumptions behind the claims made and the conclusions reached. Deduction - decision making in precisely defined contexts where rules, operating conditions, core beliefs, values, policies, principles, procedures and terminology completely determine the outcome. Deductive reasoning moves with exacting precision from the assumed truth of a set of beliefs to a conclusion which cannot be false if those beliefs are untrue. Deductive validity is rigorously logical and clear-cut. -

Ohio Rules of Evidence

OHIO RULES OF EVIDENCE Article I GENERAL PROVISIONS Rule 101 Scope of rules: applicability; privileges; exceptions 102 Purpose and construction; supplementary principles 103 Rulings on evidence 104 Preliminary questions 105 Limited admissibility 106 Remainder of or related writings or recorded statements Article II JUDICIAL NOTICE 201 Judicial notice of adjudicative facts Article III PRESUMPTIONS 301 Presumptions in general in civil actions and proceedings 302 [Reserved] Article IV RELEVANCY AND ITS LIMITS 401 Definition of “relevant evidence” 402 Relevant evidence generally admissible; irrelevant evidence inadmissible 403 Exclusion of relevant evidence on grounds of prejudice, confusion, or undue delay 404 Character evidence not admissible to prove conduct; exceptions; other crimes 405 Methods of proving character 406 Habit; routine practice 407 Subsequent remedial measures 408 Compromise and offers to compromise 409 Payment of medical and similar expenses 410 Inadmissibility of pleas, offers of pleas, and related statements 411 Liability insurance Article V PRIVILEGES 501 General rule Article VI WITNESS 601 General rule of competency 602 Lack of personal knowledge 603 Oath or affirmation Rule 604 Interpreters 605 Competency of judge as witness 606 Competency of juror as witness 607 Impeachment 608 Evidence of character and conduct of witness 609 Impeachment by evidence of conviction of crime 610 Religious beliefs or opinions 611 Mode and order of interrogation and presentation 612 Writing used to refresh memory 613 Impeachment by self-contradiction -

"What Is Evidence?" a Philosophical Perspective

"WHAT IS EVIDENCE?" A PHILOSOPHICAL PERSPECTIVE PRESENTATION SUMMARY NATIONAL COLLABORATING CENTRES FOR PUBLIC HEALTH 2007 SUMMER INSTITUTE "MAKING SENSE OF IT ALL" BADDECK, NOVA SCOTIA, AUGUST 20-23 2007 Preliminary version—for discussion "WHAT IS EVIDENCE?" A PHILOSOPHICAL PERSPECTIVE PRESENTATION SUMMARY NATIONAL COLLABORATING CENTRES FOR PUBLIC HEALTH 2007 SUMMER INSTITUTE "MAKING SENSE OF IT ALL" BADDECK, NOVA SCOTIA, AUGUST 20-23 2007 NATIONAL COLLABORATING CENTRE FOR HEALTHY PUBLIC POLICY JANUARY 2010 SPEAKER Daniel Weinstock Research Centre on Ethics, University of Montréal EDITOR Marianne Jacques National Collaborating Centre for Healthy Public Policy LAYOUT Madalina Burtan National Collaborating Centre for Healthy Public Policy DATE January 2010 The aim of the National Collaborating Centre for Healthy Public Policy (NCCHPP) is to increase the use of knowledge about healthy public policy within the public health community through the development, transfer and exchange of knowledge. The NCCHPP is part of a Canadian network of six centres financed by the Public Health Agency of Canada. Located across Canada, each Collaborating Centre specializes in a specific area, but all share a common mandate to promote knowledge synthesis, transfer and exchange. The production of this document was made possible through financial support from the Public Health Agency of Canada and funding from the National Collaborating Centre for Healthy Public Policy (NCCHPP). The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Public Health Agency of Canada. This document is available in electronic format (PDF) on the web site of the National Collaborating Centre for Healthy Public Policy at www.ncchpp.ca. La version française est disponible sur le site Internet du CCNPPS au www.ccnpps.ca. -

Who's That with Abrahams

barTHE JOURNAL OF THE NSWnews BAR ASSOCIATION | SUMMER 2008/09 Who’s that with Abrahams KC? Rediscovering Rhetoric Justice Richard O’Connor rediscovered Bullfry in Shanghai | CONTENTS | 2 President’s column 6 Editor’s note 7 Letters to the editor 8 Opinion Access to court information The costs circus 12 Recent developments 24 Features 75 Legal history The Hon Justice Foster The criminal jurisdiction of the Federal The Kyeema air disaster The Hon Justice Macfarlan Court NSW Law Almanacs online The Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina The Hon Justice Ward Saving St James Church 40 Addresses His Honour Judge Michael King SC Justice Richard Edward O’Connor Rediscovering Rhetoric 104 Personalia The current state of the profession His Honour Judge Storkey VC 106 Obituaries Refl ections on the Federal Court 90 Crossword by Rapunzel Matthew Bracks 55 Practice 91 Retirements 107 Book reviews The Keble Advocacy Course 95 Appointments 113 Muse Before the duty judge in Equity Chief Justice French Calderbank offers The Hon Justice Nye Perram Bullfry in Shanghai Appearing in the Commercial List The Hon Justice Jagot 115 Bar sports barTHE JOURNAL OF THE NSWnews BAR ASSOCIATION | SUMMER 2008-09 Bar News Editorial Committee Cover the New South Wales Bar Andrew Bell SC (editor) Leonard Abrahams KC and Clark Gable. Association. Keith Chapple SC Photo: Courtesy of Anthony Abrahams. Contributions are welcome and Gregory Nell SC should be addressed to the editor, Design and production Arthur Moses SC Andrew Bell SC Jeremy Stoljar SC Weavers Design Group Eleventh Floor Chris O’Donnell www.weavers.com.au Wentworth Chambers Duncan Graham Carol Webster Advertising 180 Phillip Street, Richard Beasley To advertise in Bar News visit Sydney 2000.