Speech-98-032:Expanding Our Universe:New Models of Success

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Honorary Degree Recipients 1977 – Present

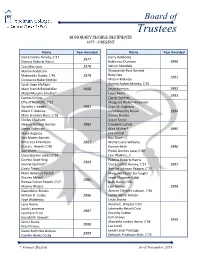

Board of Trustees HONORARY DEGREE RECIPIENTS 1977 – PRESENT Name Year Awarded Name Year Awarded Claire Collins Harvey, C‘37 Harry Belafonte 1977 Patricia Roberts Harris Katherine Dunham 1990 Toni Morrison 1978 Nelson Mandela Marian Anderson Marguerite Ross Barnett Ruby Dee Mattiwilda Dobbs, C‘46 1979 1991 Constance Baker Motley Miriam Makeba Sarah Sage McAlpin Audrey Forbes Manley, C‘55 Mary French Rockefeller 1980 Jesse Norman 1992 Mabel Murphy Smythe* Louis Rawls 1993 Cardiss Collins Oprah Winfrey Effie O’Neal Ellis, C‘33 Margaret Walker Alexander Dorothy I. Height 1981 Oran W. Eagleson Albert E. Manley Carol Moseley Braun 1994 Mary Brookins Ross, C‘28 Donna Shalala Shirley Chisholm Susan Taylor Eleanor Holmes Norton 1982 Elizabeth Catlett James Robinson Alice Walker* 1995 Maya Angelou Elie Wiesel Etta Moten Barnett Rita Dove Anne Cox Chambers 1983 Myrlie Evers-Williams Grace L. Hewell, C‘40 Damon Keith 1996 Sam Nunn Pinkie Gordon Lane, C‘49 Clara Stanton Jones, C‘34 Levi Watkins, Jr. Coretta Scott King Patricia Roberts Harris 1984 Jeanne Spurlock* Claire Collins Harvey, C’37 1997 Cicely Tyson Bernice Johnson Reagan, C‘70 Mary Hatwood Futrell Margaret Taylor Burroughs Charles Merrill Jewel Plummer Cobb 1985 Romae Turner Powell, C‘47 Ruth Davis, C‘66 Maxine Waters Lani Guinier 1998 Gwendolyn Brooks Alexine Clement Jackson, C‘56 William H. Cosby 1986 Jackie Joyner Kersee Faye Wattleton Louis Stokes Lena Horne Aurelia E. Brazeal, C‘65 Jacob Lawrence Johnnetta Betsch Cole 1987 Leontyne Price Dorothy Cotton Earl Graves Donald M. Stewart 1999 Selma Burke Marcelite Jordan Harris, C‘64 1988 Pearl Primus Lee Lorch Dame Ruth Nita Barrow Jewel Limar Prestage 1989 Camille Hanks Cosby Deborah Prothrow-Stith, C‘75 * Former Student As of November 2019 Board of Trustees HONORARY DEGREE RECIPIENTS 1977 – PRESENT Name Year Awarded Name Year Awarded Max Cleland Herschelle Sullivan Challenor, C’61 Maxine D. -

Black History Trivia Bowl Study Questions Revised September 13, 2018 B C D 1 CATEGORY QUESTION ANSWER

Black History Trivia Bowl Study Questions Revised September 13, 2018 B C D 1 CATEGORY QUESTION ANSWER What national organization was founded on President National Association for the Arts Advancement of Colored People (or Lincoln’s Birthday? NAACP) 2 In 1905 the first black symphony was founded. What Sports Philadelphia Concert Orchestra was it called? 3 The novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin was published in what Sports 1852 4 year? Entertainment In what state is Tuskegee Institute located? Alabama 5 Who was the first Black American inducted into the Pro Business & Education Emlen Tunnell 6 Football Hall of Fame? In 1986, Dexter Gordan was nominated for an Oscar for History Round Midnight 7 his performance in what film? During the first two-thirds of the seventeenth century Science & Exploration Holland and Portugal what two countries dominated the African slave trade? 8 In 1994, which president named Eddie Jordan, Jr. as the Business & Education first African American to hold the post of U.S. Attorney President Bill Clinton 9 in the state of Louisiana? Frank Robinson became the first Black American Arts Cleveland Indians 10 manager in major league baseball for what team? What company has a successful series of television Politics & Military commercials that started in 1974 and features Bill Jell-O 11 Cosby? He worked for the NAACP and became the first field Entertainment secretary in Jackson, Mississippi. He was shot in June Medgar Evers 12 1963. Who was he? Performing in evening attire, these stars of The Creole Entertainment Show were the first African American couple to perform Charles Johnson and Dora Dean 13 on Broadway. -

Graduation Speakers

COMMENCEMENT SPEAKERS (Spring 1961 – Spring 2018) 2018 Fall Christine Mann Darden NASA Executive and Engineer 2018 Spring Marian Wright Edelman Founder and President, Children’s Defense Fund 2017 Fall Chancellor W. Randolph Woodson Chancellor, NC State University 2017 Spring Nancy McFarlane Mayor of the City of Raleigh 2016 Fall Margaret Spellings President, the University of North Carolina 2016 Spring Admiral Michelle Howard Vice Chief of Naval Operations 2015 Fall Ambassador Karl Eikenberry United States Army, Retired, and former U.S. Ambassador to Afghanistan 2015 Spring France A. Córdova Director of the National Science Foundation 2014 Fall Vivian Howard Chef and Owner of the Chef & The Farmer and the Boiler Room Oyster Bar in Kinston, NC 2014 Spring David Ferriero Archivist of the United States and Head of the National Archives and Records Administration 2013 Fall Chancellor W. Randolph Woodson Chancellor, NC State University 2013 Spring Philip Freelon Founder and President of the Freelon Group and NC State Alumnus 2012 Fall Dickson B. (Doc) Hendley Founder and President of Wine to Water 2012 Spring Philip Rivers Record-setting passer for NC State and currently starting quarterback for the San Diego Chargers 2011 Fall Dr. Rajendra Pachauri Nobel-Prize winner and NC State alumnus. World leader in the study of climate change. 2011 Spring James E. Rogers President and CEO of Duke Energy 2010 Fall General Raymond T. Odierno Commander of United States Joint Forces Command Updated 09/18 2010 Spring Charles Rose Executive Editor and Anchor of the “Charlie Rose” Show 2009 Fall No speaker due to Dr. Rajendra Nobel-Prize winner and NC State Pachauri being sick alumnus. -

Congressional Record—House H 1494

H 1494 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD Ð HOUSE February 28, 1996 only tax reform but spending reduc- Congress first passed a resolution to in- up together in New Jersey. In her posi- tions and deficit reductions, which stitute a celebration of Black History tion at the Department of Energy, she gives the change to have help for work- Month. has worked tirelessly on issues ranging ing families, for seniors and for our This year, we have chosen the theme from energy development to the health children. ``African-American WomenÐYester- effects of radiation testing. She has I yield to the gentleman from Geor- day, Today, and Tomorrow'' in recogni- achieved tremendous success in nego- gia. tion of the enormous contributions tiating trade agreements with a poten- Mr. KINGSTON. Let me just say this, that African-American women have tial value to our Nation of billions of in the 1992 presidential primary, can- made to our history and culture. In dollars. didate Bill Clinton had an ad that said every field of endeavorÐpublic service, Also rendering outstanding service in this: ``Hi, I am Bill Clinton. I believe politics, law, medicine, literature, cor- the executive branch are Lorraine Mil- you deserve a change. That is why I porate management, education, and ler, who formerly served as Deputy As- have a plan to stimulate the economy, othersÐAfrican-American women are sistant to the President for Legislative starting with a middle-class tax cut.'' achievers. Affairs and now holds a post in the Now, we all know, after running on a Let me begin by recognizing the Federal Trade Commission; Alexis Her- promise of a middle-class tax cut, the women of the Black Caucus serving in man, Director of Public Liaison at the President turned around and in 1993 the 104th Congress. -

Annotated Bibliography: Women in Physics, Astronomy, and Related Disciplines

Annotated Bibliography: Women in Physics, Astronomy, and Related Disciplines Abir Am, Pnina and Dorinda Outram, eds. Uneasy Careers and Intimate Lives: Women in Science, 1787-1979. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1987. Abir Am and Outram’s volume includes a collection of essays about women in science that highlight the intersection of personal and professional spheres. All of the articles argue that the careers of women scientists are influenced by their family lives and that their family lives are impacted because of their scientific careers. This text is significant in two ways: first, it is one of the earliest examples of scholarship that moves beyond the recovering women in science, but placing them in the context of their home and work environments. Second, it suggests that historians of science can no longer ignore the private lives of their historical subjects. This volume contains four articles relating to women in physics and astronomy: Marilyn Bailey Ogilvie’s “Marital Collaboration: An Approach to Science” (pages 104-125), Sally Gregory Kohlstedt’s “Maria Mitchell and the Advancement of Women in Science” (pages 129-146), Helena M. Pycior’s “Marie Curie’s ‘Anti-Natural Path’: Time Only for Science and Family” (pages 191-215), and Peggy Kidwell’s “Cecelia Payne-Gaposchkin: Astronomy in the Family” (pages 216-238). As a unit, the articles would constitute and interesting lesson on personal and professional influences. Individually, the articles could be incorporated into lessons on a single scientist, offering a new perspective on their activities at work and at home. It complements Pycior, Slack, and Abir Am’s Creative Couples in the Sciences and Lykknes, Opitz, and Van Tiggelen’s For Better of For Worse: Collaborative Couples in the Sciences, which also look at the intersection of the personal and professional. -

2011 2011 2011Annual Report Annual Report July 1, 2010–June 30, 2011

Council on Foreign Relations Council Foreign on Council on Foreign Relations 58 East 68th Street New York, NY 10065 tel 212.434.9400 fax 212.434.9800 1777 F Street, NW Annual Report Washington, DC 20006 Ann tel 202.509.8400 ual Report fax 202.509.8490 www.cfr.org 2011 2011 2011Annual Report Annual Report July 1, 2010–June 30, 2011 Council on Foreign Relations 58 East 68th Street New York, NY 10065 tel 212.434.9400 fax 212.434.9800 1777 F Street, NW Washington, DC 20006 tel 202.509.8400 fax 202.509.8490 www.cfr.org [email protected] Officers and Directors OFFICErs DIr ectors Carla A. Hills Irina A. Faskianos Term Expiring 2012 Term Expiring 2013 Term Expiring 2014 Co-Chairman Vice President, National Program and Outreach Fouad Ajami Alan S. Blinder Madeleine K. Albright Robert E. Rubin Sylvia Mathews Burwell J. Tomilson Hill David G. Bradley Co-Chairman Suzanne E. Helm Kenneth M. Duberstein Alberto Ibargüen Donna J. Hrinak Richard E. Salomon Vice President, Development Stephen Friedman Shirley Ann Jackson Henry R. Kravis Vice Chairman Jan Mowder Hughes Carla A. Hills Joseph S. Nye Jr. James W. Owens Richard N. Haass Vice President, Human resources Jami Miscik George Rupp Frederick W. Smith President and Administration Robert E. Rubin Richard E. Salomon Fareed Zakaria Kenneth Castiglia L. Camille Massey Vice President, Membership, Term Expiring 2015 Term Expiring 2016 Richard N. Haass Chief Financial and Administrative ex officio Officer and Treasurer Corporate, and International John P. Abizaid Ann M. Fudge David Kellogg Lisa Shields Peter Ackerman Thomas H. -

Women Scientists and Inventors

CONTENTS Introduction 4 Awe-Inspiring Contributions Chapter 1 8 Lise Meitner Chapter 2 18 Pearl Kendrick Chapter 3 28 Virginia Apgar Chapter 4 38 Jane Goodall Chapter 5 47 Shirley Ann Jackson Chapter 6 57 Rosalind W. Picard Source Notes 67 For Further Research 72 Index 74 Picture Credits 79 About the Author 80 1944 for the discovery of fi ssion, but Meitner was completely excluded. In the physics community, at least, Meitner’s extraordinary talents and contributions were understood. She had recognized and named nuclear fi ssion and had calculated its energy release. In 1943 she and her nephew were invited to Los Alamos, New Mexico, to work on the atomic bomb. “I will have nothing Frisch accepted, but Meitner was ap- palled at putting her physics to military to do with a bomb!”6 use. She said, “I will have nothing to do —Lise Meitner with a bomb!”6 When she learned that the fi rst atomic bomb had been dropped on Hiroshima, Japan, in 1945, ending World War II, she was hor- rifi ed and sickened. She walked alone in the woods for hours, trying to accept what had happened. Acclaim and Sorrow Even though she had nothing to do with developing the bomb, Meitner was credited in the West with having uncovered the secrets of atomic fi ssion and making the atomic bomb possible. News reporters wrote stories about her. Former First Lady Elea- nor Roosevelt interviewed her for American radio. In 1946 she made her fi rst visit to the United States to see two sisters who had immigrated to New York and Washington and Frisch, who was still at Los Alamos. -

*Jackson Chapt 01 Final

Introduction Exploring the Unseen Some explorers lift off into space. Others dive deep beneath the sea or trek through mountains or rain forests. Shirley Ann Jackson explores the universe too, but on a smaller scale and from a different perspective. She is a physicist who investigates the world on a submicroscopic level. She studies the tiniest elements of the universe, the particles that make up all matter. Why is it so exciting to learn about things you can’t even see? Split one of those tiny particles and you could cause catastrophic destruction. Or you could harness its powerful force to improve the way we work and play and live our lives. Because of Shirley’s scientific expertise and her willingness to take on new challenges, her career has moved in exciting directions. In industry, she worked on the cutting edge of technology, discovering ways for materials to be more useful in our everyday lives. When President Bill Clinton asked her to head the Nuclear Regulatory Commission in 1995, she made sweeping changes to ensure the public’s safety, in our own country and around the world. As president of Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, she is creating unique opportunities for the next generation of scientists. How did Shirley Ann Jackson achieve so much? She began with a curious mind and a passion for uncovering the secrets that lay hidden in the world around us. ix To Shirley, the world was full of mysteries and living creatures provided the clues that could help solve them. 1 BEE SECRETS hirley Ann Jackson stood in the hot summer sun, patiently staring at a large rosebush in her family’s garden. -

Demonstration Team Lumina Team Inspirational and Practical Personal Development

25/10/2018 Lumina Team Viewer - Lumina Learning Demonstration Team Lumina Team Inspirational and Practical Personal Development © 2018 Lumina Learning https://team.luminalearning.com/demo/small?returnUrl=https:~2F~2Fteam.luminalearning.com~2Fdemo 1/9 25/10/2018 Lumina Team Viewer - Lumina Learning Demonstration Team All Three Personas combined DH CP MM RF EH AKB LVH PSG WKH MC RPF NC JK SWL GBE SER SH EF ES MF EB CH JG MF GS CW MSD FW PM ACO ID WEP MB NB SB RB LM LK JBB WCR AE RL EPH JKB SIN BP SAJ FR MP PJW Members Collective team mandala position Big Picture Thinking Adriana C. Ocampo Uria Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin Elizabeth Blackburn ACO Extraverted CP Inspiration Driven EB Introverted Dummy Project Dummy Project Dummy Project Albert Einstein Chien-Shiung Wu Enrico Fermi AE Outcome Focused CW Introverted EF Inspiration Driven Dummy Project Dummy Project Dummy Project Anna K. Behrensmeyer Dorothy Hodgkin Erwin Schroedinger AKB Inspiration Driven DH Inspiration Driven ES Big Picture Thinking Dummy Project Dummy Project Dummy Project Blaise Pascal Edmond Halley Flossie Wong-Staal BP Outcome Focused EH People Focused FW Extraverted Dummy Project Dummy Project Dummy Project Caroline Herschel Edwin Powell Hubble Frieda Robscheit-Robbins CH People Focused EPH Discipline Driven FR Down to Earth Dummy Project Dummy Project Dummy Project https://team.luminalearning.com/demo/small?returnUrl=https:~2F~2Fteam.luminalearning.com~2Fdemo 2/9 25/10/2018 Lumina Team Viewer - Lumina Learning Geraldine Seydoux Max Born Rosalind Franklin GS Extraverted MB Introverted RF People Focused Dummy Project Dummy Project Dummy Project Gertrude B. -

Honoring the Many Contributions of Black Americans

HONORING THE MANY CONTRIBUTIONS OF BLACK AMERICANS DIVERSITY • EQUITY • INCLUSION A campus-wide celebration of Black History Monthby SUNY ULSTER FACULTY and The Office of Diversity, Equity & Inclusion • Engineer who established his own machine shop in ENGINEERING Cincinnati in 1880. Later moved to New York City. GRANVILLE T. WOODS • Invented first electric railway powered by overhead lines, as well as third rail system for subways. • Invented first telegraph system able to transmit from moving trains, as well as ability to transmit voice and Morse code over the same line. • Registered over 35 patents, 1880-1907, including ones for a steam boiler furnace (1884), electric incubator (1900), and automatic air brake (1902). Picture of Granville T. Woods from Cosmopolitan magazine, c. 1895 DIVERSITY • EQUITY • INCLUSION Maya Angelou was born Marguerite Johnson in St. Louis, HUMANITIES Missouri, on April 4, 1928. She grew up in St. Louis and Stamps, MAYA ANGELOU Arkansas. She was an author, poet, historian, songwriter, playwright, dancer, stage and screen producer, director, performer, singer, and civil rights activist. She was best known for her seven autobiographical books. The first black woman director in Hollywood, Angelou wrote, produced, directed, and starred in productions for stage, film, and television. Poets.org DIVERSITY • EQUITY • INCLUSION Barack Obama served as the 44th President of the United POLITICAL SCIENCES States. His story is the American story — values from the BARACK OBAMA heartland, a middle-class upbringing in a strong family, hard work and education as the means of getting ahead, and the conviction that a life so blessed should be lived in service to others.When Barack Obama was elected president in 2008, he became the first African American to hold the office. -

2009 Annual Report

Smithsonian Institution WHAT I S ANNUAL REPORT 2009 NEXT. WHAT GRAND CHALLENGES AND PRIORITIES PAGE ENABLING THE SMITHSONIAN’S MISSION PAGE SMITHSONIAN IN 8779 PAGE BOARD OF REGENTS REPORT PAGE FINANCIAL AND PHILANTHROPY REPORTS PAGE DONORS TO THE SMITHSONIAN PAGE IS NEXT. Conventionally, annual reports detail ACHIEVEMENT, but at the Smithsonian, the biggest story of 2009 was all about OPPORTUNITY. Last year, we talked about CHARTING COURSE and announced a strategic planning process that would guide our work over the next five years. This year, we have a plan and we are proud to report that our FUTURE is taking shape. What will be different? In our aggressive pursuit of EXCELLENCE, we will deploy traditional strengths in innovative ways. We will focus our energies and resources on FOUR GRAND CHALLENGES, areas where our unique expertise can do the most good in the world. We will create and disseminate knowledge, and INTEGRATE IT ACROSS DISCIPLINES bringing the power of science, the aesthetic of art, and the insight of history to bear as only we can. We will embrace 21st-century tools to extend our reach and OPEN DOORS. We will apply our great resources to enliven education. We will PRESERVE THE COLLECTIONS that represent our heritage and the world’s treasure. We wil l partner with individuals, institutions, and nations whose interests and PASSION match our PRIORITIES so we can effec t lasting change. The stories that follow represent just a few of the ways we are turning our VISION into reality. JOIN US on the journey. Together, we can make a re al difference. -

Report Idea 1

annual report 2005 Innovation and the Integrity of Science The American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) is the world’s largest general scientific society, and publisher of the journal, Science (www.sciencemag.org). AAAS was founded in 1848, and serves 262 affiliated societies and academies of science, reaching 10 million individuals. Science has the largest paid circulation of any peer-reviewed general science journal in the world, with an estimated total readership of 1 million. The non-profit AAAS (www.aaas.org) is open to all and fulfills its mission to “advance science and serve society” through initiatives in science policy; international programs; science education; and more. For the latest research news, log onto EurekAlert!, www.eurekalert.org, the premier science-news Web site, a service of AAAS. Table of Contents 2 Welcome Letter 4 Evolution — 2005 Chronology 6 Science Policy and Security 8 International Impacts 10 Science Education and Careers 12 Science Breakthroughs 14 Engaging the Public 16 AAAS Awards 20 Golden Fund Update 22 AAAS Fellows 26 Acknowledgement of Contributors 32 Financial Summary for 2005 33 AAAS Board of Directors, Officers and Information 1 Year in Review: 2005 WELCOME FROM THE CHAIR, SHIRLEY ANN JACKSON, AND THE CEO, ALAN I. LESHNER In a global economy, our prosperity, safety, and overall well-being depend more than ever upon our capacity for innovation. Geopolitical tensions, exacerbated by an uncertain energy future, underscore the need to step up the pace of fundamental scientific discovery. In the United States, unfortunately, a quiet crisis confronts us as scientists and engineers are retiring in record numbers and too few students enter the pipeline.