Understanding Functioning and Health in Patients with Whiplash-Associated Disorders Phd Thesis, Utrecht University, the Netherlands ISBN © 2010, M.A.Schmitt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Family Name Files That Can Be Accessed in the Boerne Public Library Local and Family History Archives

FAMILY NAME FILES THAT CAN BE ACCESSED IN THE BOERNE PUBLIC LIBRARY LOCAL AND FAMILY HISTORY ARCHIVES A Abadie, Ables, Abshire Ackerman Adair, Adam, Adamek, Adamietz, Adams, Adamson, Adcock, Adkins, Adler, Adrian, Adriance, Agold, Aguirre, Ahr, Ahrlett, Alba, Albrecht, Albright, Alcorn, Alderman, Aldridge, Alexander, Alf, Alford, Algueseva, Allamon, Allen, Allison, Altgelt, Alvarez, Amason, Ammann, Ames, Anchondo, Anderson, Angell, Angle, Ansaldo, Anstiss, Appelt, Armendarez, Armstrong, Arnold, Arnott, Artz, Ashcroft, Asher, Atencio, Atkinson, Aue, Austin, Aycock, B Backer, Bacon, Bacorn, Bain, Baker, Baldwin, Ball, Balser, Bangert, Bankier, Banks, Bannister, Barbaree, Barker, Barkley, Barnard, Barnes, Barnett, Barnette, Barnhart, Baron, Barrett, Barrington, Barron, Barrows, Barta, Barteau, Bartel, Bartels, Barthlow, Barton, Basham, Bates, Batha, Bauer, Baum, Baumann, Bausch, Baxter, Bayard, Bayless, Baynton, Beagle, Bealor, Beam, Bean, Beardslee, Beasley, Beath, Beatty, Beauford, Beaver, Bechtold, Beck, Becker, Beckett, Beckley, Bedford, Bedgood, Bednar, Bedwell, Beem, Beene, Beer, Begia, Behr, Beissner, Bell, Below, Bemus, Benavides, Bender, Bennack, Benefield, Benner, Bennett, Benson, Bentley, Berger, Bergmann, Berlin, Berline, Bernal, Berne, Bernert, Bernhard, Bernstein, Berry, Besch, Beseler, Beshea, Besser, Best, Bettison, Beutnagel, Bevers, Bey, Beyer, Bickel, Bidus, Bien, Bierman, Bierschwale, Bigger, Biggs, Billingsley, Birdsong, Birkner, Bish, Bitzkie, Black, Blackburn, Blackford, Blackwell, Blair, Blaize, Blake, Blakey, Blalock, -

The German Surname Atlas Project ± Computer-Based Surname Geography Kathrin Dräger Mirjam Schmuck Germany

Kathrin Dräger, Mirjam Schmuck, Germany 319 The German Surname Atlas Project ± Computer-Based Surname Geography Kathrin Dräger Mirjam Schmuck Germany Abstract The German Surname Atlas (Deutscher Familiennamenatlas, DFA) project is presented below. The surname maps are based on German fixed network telephone lines (in 2005) with German postal districts as graticules. In our project, we use this data to explore the areal variation in lexical (e.g., Schröder/Schneider µtailor¶) as well as phonological (e.g., Hauser/Häuser/Heuser) and morphological (e.g., patronyms such as Petersen/Peters/Peter) aspects of German surnames. German surnames emerged quite early on and preserve linguistic material which is up to 900 years old. This enables us to draw conclusions from today¶s areal distribution, e.g., on medieval dialect variation, writing traditions and cultural life. Containing not only German surnames but also foreign names, our huge database opens up possibilities for new areas of research, such as surnames and migration. Due to the close contact with Slavonic languages (original Slavonic population in the east, former eastern territories, migration), original Slavonic surnames make up the largest part of the foreign names (e.g., ±ski 16,386 types/293,474 tokens). Various adaptations from Slavonic to German and vice versa occurred. These included graphical (e.g., Dobschinski < Dobrzynski) as well as morphological adaptations (hybrid forms: e.g., Fuhrmanski) and folk-etymological reinterpretations (e.g., Rehsack < Czech Reåak). *** 1. The German surname system In the German speech area, people generally started to use an addition to their given names from the eleventh to the sixteenth century, some even later. -

Family Group Sheets Surname Index

PASSAIC COUNTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY FAMILY GROUP SHEETS SURNAME INDEX This collection of 660 folders contains over 50,000 family group sheets of families that resided in Passaic and Bergen Counties. These sheets were prepared by volunteers using the Societies various collections of church, ceme tery and bible records as well as city directo ries, county history books, newspaper abstracts and the Mattie Bowman manuscript collection. Example of a typical Family Group Sheet from the collection. PASSAIC COUNTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY FAMILY GROUP SHEETS — SURNAME INDEX A Aldous Anderson Arndt Aartse Aldrich Anderton Arnot Abbott Alenson Andolina Aronsohn Abeel Alesbrook Andreasen Arquhart Abel Alesso Andrews Arrayo Aber Alexander Andriesse (see Anderson) Arrowsmith Abers Alexandra Andruss Arthur Abildgaard Alfano Angell Arthurs Abraham Alje (see Alyea) Anger Aruesman Abrams Aljea (see Alyea) Angland Asbell Abrash Alji (see Alyea) Angle Ash Ack Allabough Anglehart Ashbee Acker Allee Anglin Ashbey Ackerman Allen Angotti Ashe Ackerson Allenan Angus Ashfield Ackert Aller Annan Ashley Acton Allerman Anners Ashman Adair Allibone Anness Ashton Adams Alliegro Annin Ashworth Adamson Allington Anson Asper Adcroft Alliot Anthony Aspinwall Addy Allison Anton Astin Adelman Allman Antoniou Astley Adolf Allmen Apel Astwood Adrian Allyton Appel Atchison Aesben Almgren Apple Ateroft Agar Almond Applebee Atha Ager Alois Applegate Atherly Agnew Alpart Appleton Atherson Ahnert Alper Apsley Atherton Aiken Alsheimer Arbuthnot Atkins Aikman Alterman Archbold Atkinson Aimone -

Surname Folders.Pdf

SURNAME Where Filed Aaron Filed under "A" Misc folder Andrick Abdon Filed under "A" Misc folder Angeny Abel Anger Filed under "A" Misc folder Aberts Angst Filed under "A" Misc folder Abram Angstadt Achey Ankrum Filed under "A" Misc folder Acker Anns Ackerman Annveg Filed under “A” Misc folder Adair Ansel Adam Anspach Adams Anthony Addleman Appenzeller Ader Filed under "A" Misc folder Apple/Appel Adkins Filed under "A" Misc folder Applebach Aduddell Filed under “A” Misc folder Appleman Aeder Appler Ainsworth Apps/Upps Filed under "A" Misc folder Aitken Filed under "A" Misc folder Apt Filed under "A" Misc folder Akers Filed under "A" Misc folder Arbogast Filed under "A" Misc folder Albaugh Filed under "A" Misc folder Archer Filed under "A" Misc folder Alberson Filed under “A” Misc folder Arment Albert Armentrout Albight/Albrecht Armistead Alcorn Armitradinge Alden Filed under "A" Misc folder Armour Alderfer Armstrong Alexander Arndt Alger Arnold Allebach Arnsberger Filed under "A" Misc folder Alleman Arrel Filed under "A" Misc folder Allen Arritt/Erret Filed under “A” Misc folder Allender Filed under "A" Misc folder Aschliman/Ashelman Allgyer Ash Filed under “A” Misc folder Allison Ashenfelter Filed under "A" Misc folder Allumbaugh Filed under "A" Misc folder Ashoff Alspach Asper Filed under "A" Misc folder Alstadt Aspinwall Filed under "A" Misc folder Alt Aston Filed under "A" Misc folder Alter Atiyeh Filed under "A" Misc folder Althaus Atkins Filed under "A" Misc folder Altland Atkinson Alwine Atticks Amalong Atwell Amborn Filed under -

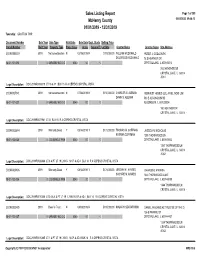

Sales Report

Sales Listing Report Page 1 of 309 McHenry County 05/04/2020 09:46:13 01/01/2019 - 12/31/2019 Township: GRAFTON TWP Document Number Sale Year Sale Type Valid Sale Sale Date Dept. Study Selling Price Parcel Number Built Year Property Type Prop. Class Acres Square Ft. Lot Size Grantor Name Grantee Name Site Address 2019R0006019 2019 Not advertised on mN 02/19/2019 N $115,000.00 WILLIAM MCDONALD PETER J. GODLEWSKI DOLORESS MCDONALD 78 S HEATHER DR 18-01-101-013 0 GARAGE/ NO O O 0040 .00 0 CRYSTAL LAKE, IL 600145018 78 S HEATHER DR CRYSTAL LAKE, IL 60014 -5018 Legal Description: DOC 2019R0006019 LT 16 & 17 BLK 15 R A CEPEKS CRYSTAL VISTA 2019R0027941 2019 Not advertised on mN 07/08/2019 N $150,000.00 CHARLES G. ALEMAN REINVEST HOMES LLC, AN ILLINOIS LIMIT DAWN S. ALEMAN 503 E ALGONQUIN RD 18-01-101-027 0 GARAGE/ NO O O 0040 .00 0 ALGONQUIN, IL 601023004 160 HEATHER DR CRYSTAL LAKE, IL 60014 - Legal Description: DOC 2019R0027941 LT 31 BLK 15 R A CEPEKS CRYSTAL VISTA 2019R0026844 2019 Warranty Deed Y 08/14/2019 Y $172,000.00 THOMAS M. COFFMAN JESSICA N. NICHOLAS KATRINA COFFMAN 1350 THORNWOOD LN 18-01-102-035 0 LDG SINGLE FAM 0040 .00 0 CRYSTAL LAKE, IL 600145042 1350 THORNWOOD LN CRYSTAL LAKE, IL 60014 -5042 Legal Description: DOC 2019R0026844 LT 6 & PT LT 19 LYING N OF & ADJ BLK 14 R A CEPEKS CRYSTAL VISTA 2019R0010406 2019 Warranty Deed Y 04/12/2019 Y $174,000.00 JEREMY M. -

Start Number Name Surname Team City, Country Time 11001 Tommy

Start number Name Surname Team City, Country Time 11001 Tommy Frølund Jensen Kongens lyngby, Denmark 89:20:46 11002 Emil Boström Lag Nord Linköping, Sweden 98:19:04 11003 Lovisa Johansson Lag Nord Burträsk, Sweden 98:19:02 11005 Maurice Lagershausen Huddinge, Sweden 102:01:54 11011 Hyun jun Lee Korea, (south) republic of 122:40:49 11012 Viggo Fält Team Fält Linköping, Sweden 57:45:24 11013 Richard Fält Team Fält Linköping, Sweden 57:45:28 11014 Rasmus Nummela Rackmannarna Pjelax, Finland 98:59:06 11015 Rafael Nummela Rackmannarna Pjelax, Finland 98:59:06 11017 Marie Zølner Hillerød, Denmark 82:11:49 11018 Niklas Åkesson Mellbystrand, Sweden 99:45:22 11019 Viggo Åkesson Mellbystrand, Sweden 99:45:22 11020 Damian Sulik #StopComplaining Siegen, Germany 101:13:24 11023 Bruno Svendsen Tylstrup, Denmark 74:48:08 11024 Philip Oswald Lakeland, USA 55:52:02 11025 Virginia Marshall Lakefield, Canada 55:57:54 11026 Andreas Mathiasson Backyard Heroes Ödsmål, Sweden 75:12:02 11028 Stine Andersen Brædstrup, Denmark 104:35:37 11030 Patte Johansson Tiger Södertälje, Sweden 80:24:51 11031 Frederic Wiesenbach BB Dahn, Germany 101:21:50 11032 Romea Brugger BB Berlin, Germany 101:22:44 11034 Oliver Freudenberg Heyda, Germany 75:07:48 11035 Jan Hennig Farum, Denmark 82:11:50 11036 Robert Falkenberg Farum, Denmark 82:11:51 11037 Edo Boorsma Sint annaparochie, Netherlands 123:17:34 11038 Trijneke Stuit Sint annaparochie, Netherlands 123:17:35 11040 Sebastian Keck TATSE Gieäen, Germany 104:08:01 11041 Tatjana Kage TATSE Gieäen, Germany 104:08:02 11042 Eun Lee -

Human Genetics and Clinical Aspects of Neurodevelopmental Disorders

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/000687; this version posted October 6, 2014. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. Human genetics and clinical aspects of neurodevelopmental disorders Gholson J. Lyon1,2,3,*, Jason O’Rawe1,3 1Stanley Institute for Cognitive Genomics, One Bungtown Road, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, NY, USA, 11724 2Institute for Genomic Medicine, Utah Foundation for Biomedical Research, E 3300 S, Salt Lake City, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 84106 3Stony Brook University, 100 Nicolls Rd, Stony Brook, NY, USA, 11794 * Corresponding author: Gholson J. Lyon Email: [email protected] Other author emails: Jason O'Rawe: [email protected] 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/000687; this version posted October 6, 2014. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. Introduction “our incomplete studies do not permit actual classification; but it is better to leave things by themselves rather than to force them into classes which have their foundation only on paper” – Edouard Seguin (Seguin, 1866) “The fundamental mistake which vitiates all work based upon Mendel’s method is the neglect of ancestry, and the attempt to regard the whole effect upon off- spring, produced by a particular parent, as due to the existence in the parent of particular structural characters; while the contradictory results obtained by those who have observed the offspring of parents apparently identical in cer- tain characters show clearly enough that not only the parents themselves, but their race, that is their ancestry, must be taken into account before the result of pairing them can be predicted” – Walter Frank Raphael Weldon (Weldon, 1902). -

Surname First Name Categorisation Abadin Jose Luis Silver Abbelen

2018 DRIVERS' CATEGORISATION LIST Updated on 09/07/2018 Drivers in red : revised categorisation Drivers in blue : new categorisation Surname First name Categorisation Abadin Jose Luis Silver Abbelen Klaus Bronze Abbott Hunter Silver Abbott James Silver Abe Kenji Bronze Abelli Julien Silver Abergel Gabriele Bronze Abkhazava Shota Bronze Abra Richard Silver Abreu Attila Gold Abril Vincent Gold Abt Christian Silver Abt Daniel Gold Accary Thomas Silver Acosta Hinojosa Julio Sebastian Silver Adam Jonathan Platinum Adams Rudi Bronze Adorf Dirk Silver Aeberhard Juerg Silver Afanasiev Sergei Silver Agostini Riccardo Gold Aguas Rui Gold Ahlin-Kottulinsky Mikaela Silver Ahrabian Darius Bronze Ajlani Karim Bronze Akata Emin Bronze Aksenov Stanislas Silver Al Faisal Abdulaziz Silver Al Harthy Ahmad Silver Al Masaood Humaid Bronze Al Qubaisi Khaled Bronze Al-Azhari Karim Bronze Alberico Neil Silver Albers Christijan Platinum Albert Michael Silver Albuquerque Filipe Platinum Alder Brian Silver Aleshin Mikhail Platinum Alesi Giuliano Silver Alessi Diego Silver Alexander Iradj Silver Alfaisal Saud Bronze Alguersuari Jaime Platinum Allegretta Vincent Silver Alleman Cyndie Silver Allemann Daniel Bronze Allen James Silver Allgàuer Egon Bronze Allison Austin Bronze Allmendinger AJ Gold Allos Manhal Bronze Almehairi Saeed Silver Almond Michael Silver Almudhaf Khaled Bronze Alon Robert Silver Alonso Fernando Platinum Altenburg Jeff Bronze Altevogt Peter Bronze Al-Thani Abdulrahman Silver Altoè Giacomo Silver Aluko Kolawole Bronze Alvarez Juan Cruz Silver Alzen -

Field Hockey Name School Year Major Hometown Amanda Bennison Indiana Jr

Field Hockey Name School Year Major Hometown Amanda Bennison Indiana Jr. Sport Communication‐Broadcast Poynton, England Hannah Boyer Indiana Sr. Professional Health Education Louisville, Ky. Mollie Getzfread Indiana Fr. Biology Plymouth Meeting, Pa. Audra Heilman Indiana Jr. Elementary Education Easton, Pa. Corinne Karch Indiana Jr. Chemistry San Diego, Calif. Karen Lorite Indiana So. Neuroscience Terrassa, Spain Gabrielle Olshemski Indiana Jr. History Shaverton, Pa. Rachel Stauffer Indiana So. Journalism Ephrata, Pa. Nicole Volgraf Indiana Jr. Apparel Merchandising Lafayette Hill, Pa. Leisure Studies and Aubrey Coleman Iowa Sr. Mickleton, N.J. Journalism/Mass Communications Brynn Gitt Iowa Jr. Electrical Engineering Lumberton, N.J. Dani Hemeon Iowa Jr. Human Physiology Gilroy, Calif. Elizabeth Leh Iowa So. English East Stroudsburg, Pa. Kelsey Mitchell Iowa Sr. Accounting Berlin, N.J. Danielle Peirson Iowa Sr. Elementary Education Conestoga, Pa. Nikola Schultheis Iowa Sr. Finance Hamburg, Germany Marike Stribos Iowa Sr. Finance Brussels, Belgium Sara Watro Iowa Jr. Elementary Education Audubon, Pa. Literature, Science And The Jaime Dean Michigan So. Marathon, N.Y. Arts/Undeclared Literature, Science And The Mackenzie Ellis Michigan Jr. Madison, N.J. Arts/Undeclared Sammy Gray Michigan Sr. Sociology Wilmette, Ill. Lauren Hauge Michigan Sr. Environment Tulsa, Okla. Hertogenbosch, Chris Lueb Michigan So. Computer Science Netherlands Rachael Mack Michigan Sr. English Bromsgrove, England West Vancouver, Taryn Mark Michigan So. Art And Design British Columbia Ainsley McCallister Michigan Sr. Movement Science Ann Arbor, Mich. Literature, Science And The Shannon Scavelli Michigan So. Yorktown Heights, N.Y. Arts/Undeclared Leslie Smith Michigan Sr. General Studies Hummelstown, Pa. Lauren Thomas Michigan So. Art And Design Aylesbury, England Allie Ahern Michigan State Jr. -

Environment, Cultures, and Social Change on the Great Plains: a History of Crow Creek Tribal School

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Dissertations Graduate College 12-2000 Environment, Cultures, and Social Change on the Great Plains: A History of Crow Creek Tribal School Robert W. Galler Jr. Western Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Galler, Robert W. Jr., "Environment, Cultures, and Social Change on the Great Plains: A History of Crow Creek Tribal School" (2000). Dissertations. 3376. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations/3376 This Dissertation-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ENVIRONMENT, CULTURES, AND SOCIAL CHANGE ON THE GREAT PLAINS: A HISTORY OF CROW CREEK TRIBAL SCHOOL by Robert W. Galler, Jr. A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillmentof the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History WesternMichigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan December 2000 Copyright by Robert W. Galler, Jr. 2000 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many people provided assistance, suggestions, and support to help me complete this dissertation. My study of Catholic Indian education on the Great Plains began in Dr. Herbert T. Hoover's American Frontier History class at the University of South Dakota many years ago. I thank him for introducing me to the topic and research suggestions along the way. Dr. Brian Wilson helped me better understand varied expressions of American religious history, always with good cheer. -

PETITION List 04-30-13 Columns

PETITION TO FREE LYNNE STEWART: SAVE HER LIFE – RELEASE HER NOW! • 1 Signatories as of 04/30/13 Arian A., Brooklyn, New York Ilana Abramovitch, Brooklyn, New York Clare A., Redondo Beach, California Alexis Abrams, Los Angeles, California K. A., Mexico Danielle Abrams, Ann Arbor, Michigan Kassim S. A., Malaysia Danielle Abrams, Brooklyn, New York N. A., Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Geoffrey Abrams, New York, New York Tristan A., Fort Mill, South Carolina Nicholas Abramson, Shady, New York Cory a'Ghobhainn, Los Angeles, California Elizabeth Abrantes, Cambridge, Canada Tajwar Aamir, Lawrenceville, New Jersey Alberto P. Abreus, Cliffside Park, New Jersey Rashid Abass, Malabar, Port Elizabeth, South Salma Abu Ayyash, Boston, Massachusetts Africa Cheryle Abul-Husn, Crown Point, Indiana Jamshed Abbas, Vancouver, Canada Fadia Abulhajj, Minneapolis, Minnesota Mansoor Abbas, Southington, Connecticut Janne Abullarade, Seattle, Washington Andrew Abbey, Pleasanton, California Maher Abunamous, North Bergen, New Jersey Andrea Abbott, Oceanport, New Jersey Meredith Aby, Minneapolis, Minnesota Laura Abbott, Woodstock, New York Alexander Ace, New York, New York Asad Abdallah, Houston, Texas Leela Acharya, Toronto, Canada Samiha Abdeldjebar, Corsham, United Kingdom Dennis Acker, Los Angeles, California Mohammad Abdelhadi, North Bergen, New Jersey Judith Ackerman, New York, New York Abdifatah Abdi, Minneapolis, Minnesota Marilyn Ackerman, Brooklyn, New York Hamdiya Fatimah Abdul-Aleem, Charlotte, North Eddie Acosta, Silver Spring, Maryland Carolina Maria Acosta, -

Undergraduate.Pdf

Commencement 2020 t UNDERGRADUATE STUDENT EDITION 1 Commencement 2020 t CONTENTS 3 Message from the University President 4 College of Community and Public Affairs 8 Decker College of Nursing and Health Sciences 13 Harpur College of Arts and Sciences 30 School of Management 36 Thomas J. Watson School of Engineering and Applied Science 43 Honors and Special Programs 60 About Binghamton University 63 Trustees, Council and Administration 2 MESSAGE FROM THE UNIVERSITY PRESIDENT MESSAGE FROM THE UNIVERSITY PRESIDENT raduates, parents and friends: Commencement is always the highlight of the academic year, for the students we are honoring, especially, but also for the faculty and staff who have Ghelped our students achieve so much. When the COVID-19 pandemic abruptly changed our lives this spring, sending students home and curtailing so many of the activities we all would have experienced had they remained on campus, most painful was the postponement of the University’s Commencement exercises that are traditionally the highlight of the academic year. Our graduates have gained the experiences and knowledge that their careers and future engagements will demand of them. Ours is a campus where students learn by doing, and our graduates have already proven themselves — winning prestigious case competitions and grants, publishing papers that have gained acclaim from scientists and scholars, and bettering their communities through hands-on internships and practicums. Outside the classroom, they have embraced their responsibilities as active members of the community. They’ve raised funds to combat deadly disease, provided food for the hungry, taught younger students in local schools and traveled across the globe to work with and learn from their international peers.