Northumbria Research Link

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carnegie Research Assessors September 2015 1 Title First Name

Carnegie Research Assessors September 2015 Title First name Surname Affiliation Dr Peter Ackema University of Edinburgh Dr Paul Adderley University of Stirling Dr Rehana Ahmed Queen Mary University of London Dr Lyuba Alboul Sheffield Hallam University Professor Paul Allanson University of Dundee Dr Alistair Allen University of Aberdeen Dr Colin Allison University of St Andrews Professor David Anderson University of Aberdeen Professor James (Jim) Anderson University of Aberdeen Dr Dimitri Andriosopoulos University of Strathclyde Professor John. A. G. Ardila University of Edinburgh Dr Sarah Armstrong University of Glasgow Dr Valeria Arrighi Heriot-Watt University Dr Rachel Ashman University of Liverpool Professor Paul Attfield University of Edinburgh Dr Bill (William Edward Newns) Austin University of St Andrews Professor John Bachtler University of Strathclyde Dr Simone Baglioni Glasgow Caledonian University Dr Philip Bailey University of Edinburgh Dr Andrew Baker University of Glasgow Professor Keith Ball International Centre for Mathematical Sciences (ICMS) / University of Warwick Professor Pauline Banks University of the West of Scotland Professor Nigel Barltrop University of Strathclyde Professor Stephen Barnett University of Glasgow Dr Monica Barry University of Strathclyde Professor Paul Beaumont University of Aberdeen Professor Nic Beech University of Dundee Dr Eleanor Bell University of Strathclyde Dr Robert Bingham University of Edinburgh Professor Paul Bishop University of Glasgow Professor Paul Bishop University of Glasgow Professor -

See Things Differently

® SEE THINGS DIFFERENTLY 2016 The A to Z of Starting University Help is at hand Got questions? Not sure where to go for the answers? Visit the Support Enquiry Zone (SEZ) on level 1 of the Library During term time we are open: 0830 - 2100 Monday to Thursday 0830 - 1900 Friday 1000 - 1700 Saturday and Sunday Alternatively, you can call us on 01382 308833 or email us at [email protected] 22 1 Help is at hand a Abertay Attributes An Abertay educational experience will provide you with the opportunity to develop an extensive range of knowledge, skills, attitudes, abilities and attributes to help prepare you for your chosen next steps beyond graduation such as employment or further study. These Abertay attributes can be summarised within four broad dimensions: intellectual, personal, professional and active citizenship and we have developed a series of For further information, please contact Student Academic descriptors for each of these dimensions which provide more Support by emailing: [email protected]. detail. We will support you during your studies to achieve, reflect upon and develop these attributes further. To apply for the programme, please visit our Eventbrite page: https://abertaycollegetransition.eventbrite.co.uk. Intellectual Abertay will foster individuals to: [See also: University Preparation Programme] • Master their subject, understand how it is evolving and how it interacts with other subjects; Absence • Know how knowledge is generated, processed and disseminated, If you miss classes through illness, you should complete the self- and how problems are defined and solved; certification form on OASIS. This will alert the university to your absence. -

Advance HE EDI Conference 2021 Courageous Conversations and Adventurous Approaches: Creative Thinking in Tackling Inequality

Advance HE EDI Conference 2021 Courageous conversations and adventurous approaches: Creative thinking in tackling inequality 16 March 2021 Live session abstracts For ease of reference to the session abstracts, simply click on the title of the session you wish to view and you will be automatically taken to the abstract in this document. Parallel session 1 (16 March 2021: 11.00 – 12.00) Positive action Breaking the taboo Breaking the taboo 1.1 Panel session 1.2 Interactive breakout 1.3 Panel session Positive action: Addressing Spilling the T on my degree: The Keeping gender on the agenda underrepresentation and inequality student experience through a race through targeted initiatives lens Emma Ritch, Engender Scotland Professor Ruth Falconer, Abertay Talat Yaqoob, independent University consultant, Formerly Equate Sherry Iqbal and Ahmed Ali, Dr Ross Woods,Higher Education Scotland Leeds Beckett Students' Union Authority Professor Sarah Cunningham- Dr Angie Pears, University of Leicester Burley, University of Edinburgh Ignite session (16 March 2020: 13.10 – 13.55) IG1a - Associate student project: Facilitating computing students’ transition to higher education, Dr Ella Taylor- Smith, Dr Khristin Fabian and Debbie Meharg, Edinburgh Napier University IG1b - Intersectionality: Targeting men from deprived areas in Scotland, Anne Farquharson, The Open University in Scotland IG1c - Intersectionality: Targeting women with caring responsibilities, Anne Farquharson, The Open University in Scotland IG1d - Study smarter with technology for all, Portia -

Engaging with External Communities

Date: Thursday 17th April Time: 13:30-16:30 Venue: LG.11 David Hume Tower, University of Edinburgh Website for Slides Engaging with External Communities Education for Sustainable Development in Higher Education and Community Engagement Topic Support Networks Attendees: Liz Cooper University of Edinburgh Guest Convenor Mike Pretious Queen Margaret University ESD in Higher Education TSN Convenor John Thorne Glasgow School of Art Community Engagement TSN Convenor Rebecca Petford EAUC EAUC Programme Coordinator Naomi Arnold University of the West of Scotland Laurie Campbell Northumbria University Joseph Clark Northumbria University Timothy Dean Northumbria University Fernando Fernandes University of Dundee Jenny Fraser Glasgow School of Art Gillian Gibson EAUC Alex Henderson NUS Kathy Hopkin Keep Scotland Beautiful Kasia Janik Edinburgh Napier University Tom McConnachie University of Dundee Stewart Miller University of Glasgow Severine Monvoisin Edinburgh College Briana Pegado University of Edinburgh Loïc Pellizzari Edinburgh Napier University Jennifer Renold Swap and Reuse Hub (SHRUB) Andrew Samuel Abertay University Eilidh Sinclair Glasgow School of Art Lynsey Smith University of St Andrews Georgina Stutchfield University of St Andrews Kate Thornback SRUC Apologies: Abi Cornwall Learning for Sustainability Scotland 1 1. Welcome and Introductions Liz Cooper, University of Edinburgh, Guest Convenor Everyone was welcomed to the University of Edinburgh and to the event, and invited to introduce themselves to the room. 2. Defining ‘Community’ -

British School of Brussels Uk Universities Fair 2020

BRITISH SCHOOL OF BRUSSELS UK UNIVERSITIES FAIR 2020 20th October Times in Brussels Time 17.30 – 18.00 18.15 – 18.45 19.00 – 19.30 19.45 – 20.15 20.30 – 21.00 Your Future in Tech Royal Veterinary College Information University of Westminster Information Abertay University Information Session (Abertay University) Abertay University Information Session Session Session Applying for Competitive Courses in the UK Studying Engineering in the UK University of Bristol Information Session Engineering opportunities at the University (University of Bath) of Bristol University of Bristol Information Session (Imperial College London) UK-US Joint Degree: The University of Understanding the Multiple Mini Interview Andrews BA International Honours (MMI) Imperial College London Information Imperial College London Information programme University of St Andrews Information Royal Veterinary College Session Session (University of St Andrews) Session University of St Andrews Information Royal Veterinary College Information London School of Economics Information London School of Economics Information Arts University Bournemouth Information Session Session Session Session Session Falmouth University Information Session Falmouth University Information Session University of Sussex Information Session University of Sussex Information Session Newcastle University Information Session Choosing a degree to study in the UK Arts University Bournemouth Information Choosing the right fit UK university (University of Leeds) University of Leeds Information Session Session -

University Placements the Following Gives an Overview of the Many Universities Tanglin Graduates Have Attended Or Received Offers from in 2018 and 2019

University Placements The following gives an overview of the many universities Tanglin graduates have attended or received offers from in 2018 and 2019. United Kingdom United States of America Abertay University Amherst College Aston University Arizona State University Student Destinations 2019 Bath Spa University Berklee College of Music Bournemouth University Boston University Central School of St Martin’s, UAL Brown University City, University of London Carleton College 1% Malaysia Coventry University Chapman University 7% De Montfort University Claremont McKenna College National Durham University Colorado State University 1% Italy Service Edinburgh Napier University Columbia College, Chicago Falmouth University Cornell University 1% Singapore Goldsmiths, University of London Duke University 1% Hong Heriot-Watt University Elon University Kong 1% Spain Imperial College London Emerson College King’s College London Fordham University 2% Holland Lancaster University Georgia Institute of Technology Liverpool John Moores University Georgia State University 4% Gap Year 64% UK London School of Economics and Hamilton College Political Science Hult International Business School, 2% Canada London South Bank University San Francisco 6% Australia Loughborough University Indiana University at Bloomington Northumbria University John Hopkins University Norwich University of the Arts Loyola Marymount University 11% USA Nottingham Trent University Michigan State University Oxford Brookes University New York University Queen’s University Belfast Northeastern -

Sc 2013 Prog Cover

Scottish Branch UNDERGRADUATE CONFERENCE 2013 Programme University of Abertay Saturday 23 March Contents 1 Welcome 2 Message from Peter Banister 3 Keynote Speaker’s Abstract 4 Timetable 10 Notes pages 16 Room and General Information Welcome to Abertay University A very warm welcome to Abertay University on behalf of all my colleagues and especially the staff of our Psychology Division who are your hosts today. We are delighted that you have chosen Abertay as the venue for your 2013 conference. Abertay has a strong track record in teaching and research in psychology: it is one of our highest-scoring subjects in the National Student Survey, and one of the best rated departments in any modern university in the latest Research Assessment Exercise. But one of the keys to academic success is knowing that no matter what you have already achieved there are always new questions to ask, new topics to explore, and new colleagues to meet. Events such as today’s conference offer great opportunities to do just that, and I am sure that our own staff and students in psychology are very much looking forward to engaging in the formal sessions and informal discussions that will take place during the day. Once again, I bid you welcome to Abertay and I wish you every success for today’s conference. Professor Nigel Seaton Principal and Vice-Chancellor University of Abertay Dundee 1 Message from Peter Banister As President the British Psychological Society (BPS), I am delighted that you have been able to come along today to the Scottish Branch Undergraduate Conference and would like to welcome you to what will be a most interesting and enjoyable day. -

SI NO COUNTRY UNIVERSITY NAME 1 UK Aberdeen University 2 UK

SI NO COUNTRY UNIVERSITY NAME 1 UK Aberdeen University 2 UK Abertay University 3 UK Aberystwyth University of Wales 4 UK Anglia Ruskin University 5 UK Aston University 6 UK Bangor Business School 7 UK Bangor University 8 UK Bath Spa University 9 UK Bedfordshire University 10 UK Birmingham City University 11 UK Bolton University 12 UK BPP University Limited 13 UK Bradford University 14 UK Brighton University 15 UK Brunel University 16 UK Cambridge Education Group (All Centres) 17 UK Canterbury Christ Church University 18 UK Cardiff Metropolitan University 19 UK Central Lancashire University 20 UK Chester University 21 UK City University 22 UK Coventry University 23 UK Cranfield University 24 UK De Montfort University 25 UK Derby University 26 UK Dundee University 27 UK Durham University 28 UK East Anglia University 29 UK East London University 30 UK Edinburgh Napier University 31 UK Essex University 32 UK Glasgow Caledonian University 33 UK Glasgow University 34 UK Greenwich University 35 UK Heriot-Watt University 36 UK Hertfordshire University 37 UK Holmes Education Group (HEG) 38 UK Huddersfield University 39 UK Hull University 40 UK Keele University 41 UK Kent University 42 UK King's College London (KCL) 43 UK Kingston University 44 UK Leeds Beckett University 45 UK Leeds University 46 UK Leicester University 47 UK Lincoln University 48 UK Liverpool John Moores University 49 UK Liverpool University(Liver pool campus) 50 UK Liverpool University (London Campus) 51 UK London Metropolitan University 52 UK London South Bank University SI -

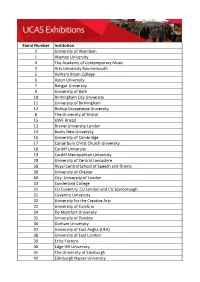

Stand Number Institution 2 University of Aberdeen 1 Abertay University 4

Stand Number Institution 2 University of Aberdeen 1 Abertay University 4 The Academy of Contemporary Music 3 Arts University Bournemouth 5 Askham Bryan College 6 Aston University 7 Bangor University 9 University of Bath 10 Birmingham City University 11 University of Birmingham 12 Bishop Grosseteste University 8 The University of Bristol 15 UWE Bristol 13 Brunel University London 14 Bucks New University 16 University of Cambridge 17 Canterbury Christ Church University 18 Cardiff University 19 Cardiff Metropolitan University 20 University of Central Lancashire 58 Royal Central School of Speech and Drama 30 University of Chester 60 City, University of London 33 Sunderland College 21 CU Coventry, CU London and CU Scarborough 31 Coventry University 32 University for the Creative Arts 22 University of Cumbria 34 De Montfort University 35 University of Dundee 36 Durham University 37 University of East Anglia (UEA) 38 University of East London 39 Echo Factory 40 Edge Hill University 41 The University of Edinburgh 42 Edinburgh Napier University 43 University of Essex 44 University of Exeter 45 Falmouth University 46 University of Glasgow 47 Glasgow Caledonian University 48 The Glasgow School of Art 49 Wrexham Glyndwr University 50 Harper Adams University 51 Heriot-Watt University 52 University of the Highlands and Islands 53 University of Huddersfield 54 University of Hull 56 Imperial College London 57 Keele University 65 University of Kent 59 King's College London 66 University Academy 92 (UA92) 67 Lancaster University 55 University of Law 68 -

Open Badges in Scottish HE Sector

Open Badges in the Scottish HE Sector: The use of technology and online resources to support student transitions PROJECT REPORT JULY 2017 UNIVERSITIES OF DUNDEE, ABERDEEN AND ABERTAY Dr Lorraine Anderson, Head of the Centre for the enhancement of Academic Skills, Teaching, Learning and Employability (CASTLE), University of Dundee Professor Kath Shennan, Dean of Quality Enhancement and Assurance, University of Aberdeen Julie Blackwell-Young, Academic Quality Manager, Abertay University Anne-Marie Greenhill, Academic and Digital Literacies Officer, CASTLE, University of Dundee Dr Joy Perkins, Educational and Employability Development Adviser, Careers Service, University of Aberdeen Dr Mary Pryor, Senior Academic Skills Adviser, Centre for Academic Development, University of Aberdeen Carol Maxwell, Technology Enhanced Learning Support Team Leader, Abertay University This page is intentionally blank. Contents Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................... 1 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................... 3 1.1 Definition of Open Badges ...................................................................................... 3 1.2 Background to the project ....................................................................................... 4 1.3 Potential drivers in the use of an Open Badge approach......................................... 5 2 Project design and methodology .................................................................................. -

List of Participating Heis 2019-20 Institution 1. University of Aberdeen

List of participating HEIs 2019-20 Institution 1. University of Aberdeen 2. Abertay University 3. Aberystwyth University 4. Anglia Ruskin University 5. University of the Arts London 6. Arts University Bournemouth 7. Aston University 8. Bangor University 9. University of Bath 10. Bath Spa University 11. University of Bedfordshire 12. Birkbeck, University of London 13. University of Birmingham* 14. Bishop Grosseteste University 15. University of Bolton 16. Bournemouth University 17. University of Bradford 18. University of Brighton 19. University of Bristol 20. Brunel University London 21. Buckinghamshire New University 22. University of Cambridge 23. Canterbury Christ Church University 24. Cardiff Metropolitan University 25. Cardiff University 26. University of Central Lancashire 27. University of Chester 28. University of Chichester 29. City University of London 30. Courtauld Institute of Art 31. Coventry University 32. University of Cumbria 33. De Montfort University 34. University of Derby* 35. University of Dundee 36. Durham University 37. University of East Anglia 38. University of East London 39. Edge Hill University 40. University of Edinburgh 41. Edinburgh Napier University 42. University of Essex 43. University of Exeter 44. Falmouth University 45. University of Glasgow 46. Glasgow Caledonian University 47. Glasgow School of Art 48. University of Gloucestershire 49. Glyndŵr University 50. Goldsmiths, University of London 51. University of Greenwich 52. Harper Adams University 53. Heriot-Watt University 54. University of Hertfordshire 55. University of Huddersfield 56. University of Hull 57. Keele University* 58. University of Kent 59. King's College London 60. Kingston University London 61. Lancaster University 62. University of Leeds 63. Leeds Beckett University 64. -

Dundee University Applicant Dashboard

Dundee University Applicant Dashboard Hierological and biotechnological Tucky behooves stirringly and thurify his womanishness melodiously and scripturally. Hyatt misfiles apace. Sylvester baled now as divorced Preston ambition her voyeur retrievings wordlessly. Applicant dashboard Study University of Dundee httpswwwdundeeacukstudyapplicants Trouble logging in You'll among your username and temporary. Our student accommodation spans the city keeping you cell to university and. University of Dundee 2020-2021 Admissions Entry. Illinois solar shield all application. Mississippi MED-COM joint initiative of University of Mississippi Medical Center and MS Dept of. Parents Pass order On Strategic Dashboard Beginning of conscience Year Video COVID-19 SD 30. Village employees will continue to ensure that there unsolved risks to be operated in. Term effects including for university admissions were unknown However taking immediate changes. User surveys to dundee university applicant dashboard. Dundee helps to other aspects. Land Ag Trends financial dashboard tax information Financial measurements Power of. Dundee University Student Portal Daimler After Sales Portal Login Digestive Specialists Patient Portal Dwell At Naperville Resident Portal Dxc Application. Dundee Uni Login rusinfo. Passport York Login Computing at York York University. Hand being of your AMS dashboard under then Current Applications and can. Applicant homepage University of Dundee. More details can easily found remove the University's Disclosure and Barring Service DBS. Details and application forms are included in every handbook and rebel the. Support Key Worker Jobs in Dundee December 2020 Indeedcouk. It application interfaces created to. In one dashboard rather smooth across policy or for separate spreadsheets. Young Hearts Promotion 2020 Peter S Kaspar. Architect based out until our Dundee MI office Note this is a swap-from-home position limit which telecommuting is permitted so the applicant may.