Is Chivalry Really Dead? – an Exploration of Chivalry and Masculinity in Medieval and American Literature Darcy Egan John Carroll University, [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chivalry in Western Literature Richard N

Rollins College Rollins Scholarship Online Master of Liberal Studies Theses 2012 The nbU ought Grace of Life: Chivalry in Western Literature Richard N. Boggs Rollins College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, European History Commons, Medieval History Commons, and the Medieval Studies Commons Recommended Citation Boggs, Richard N., "The nbouU ght Grace of Life: Chivalry in Western Literature" (2012). Master of Liberal Studies Theses. 21. http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls/21 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Rollins Scholarship Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Liberal Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of Rollins Scholarship Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Unbought Grace of Life: Chivalry in Western Literature A Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Liberal Studies by Richard N. Boggs May, 2012 Mentor: Dr. Thomas Cook Reader: Dr. Gail Sinclair Rollins College Hamilton Holt School Master of Liberal Studies Program Winter Park, Florida The Unbought Grace of Life: Chivalry in Western Literature By Richard N. Boggs May, 2012 Project Approved: ________________________________________ Mentor ________________________________________ Reader ________________________________________ Director, Master of Liberal Studies Program ________________________________________ Dean, Hamilton Holt School Rollins College Dedicated to my wife Elizabeth for her love, her patience and her unceasing support. CONTENTS I. Introduction 1 II. Greek Pre-Chivalry 5 III. Roman Pre-Chivalry 11 IV. The Rise of Christian Chivalry 18 V. The Age of Chivalry 26 VI. -

Masculinity and Chivalry: the Tenuous Relationship of the Sacred and Secular in Medieval Arthurian Literature

MASCULINITY AND CHIVALRY: THE TENUOUS RELATIONSHIP OF THE SACRED AND SECULAR IN MEDIEVAL ARTHURIAN LITERATURE by KACI MCCOURT DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Texas at Arlington August, 2018 Arlington, Texas Supervising Committee: Kevin Gustafson, Supervising Professor Jacqueline Fay James Warren i ABSTRACT Masculinity and Chivalry: The Tenuous Relationship of the Sacred and Secular in Medieval Arthurian Literature Kaci McCourt, Ph.D. The University of Texas at Arlington, 2018 Supervising Professors: Kevin Gustafson, Jacqueline Fay, and James Warren Concepts of masculinity and chivalry in the medieval period were socially constructed, within both the sacred and the secular realms. The different meanings of these concepts were not always easily compatible, causing tensions within the literature that attempted to portray them. The Arthurian world became a place that these concepts, and the issues that could arise when attempting to act upon them, could be explored. In this dissertation, I explore these concepts specifically through the characters of Lancelot, Galahad, and Gawain. Representative of earthly chivalry and heavenly chivalry, respectively, Lancelot and Galahad are juxtaposed in the ways in which they perform masculinity and chivalry within the Arthurian world. Chrétien introduces Lancelot to the Arthurian narrative, creating the illicit relationship between him and Guinevere which tests both his masculinity and chivalry. The Lancelot- Grail Cycle takes Lancelot’s story and expands upon it, securely situating Lancelot as the best secular knight. This Cycle also introduces Galahad as the best sacred knight, acting as redeemer for his father. Gawain, in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, exemplifies both the earthly and heavenly aspects of chivalry, showing the fraught relationship between the two, resulting in the emasculating of Gawain. -

The Rules of the Sovereign Order 2012

SOVEREIGN ORDER OF ST. JOHN OF JERUSALEM, KNIGHTS HOSPITALLER THE RULES OF THE SOVEREIGN ORDER 2012 Under The Constitution of H.M. King Peter II of 1964 And including references RULES TABLE OF CONTENTS I NAME, TRADITION [Const. Art. 1] 4 II PURPOSE [Const. Art 2] 6 III` LEGAL STATUS [Const. Art. 3] 7 IV FINANCE [Const. Art. 4] 10 V HEREDITARY PROTECTOR & HEREDITARY KNIGHTS [Const. Art.5] 11 VI GOVERNMENT 12 A. GRAND MASTER [Const. Art 10] B. SOVEREIGN COUNCIL [Const. Art. 7] C. PETIT CONSEIL [Const. Art. 8] D. COURTS OF THE ORDER [Const. Art. 9] VII THE PROVINCES OF THE ORDER [Const. Art. 11] 33 A. GRAND PRIORIES [Const. Art. 11.5] B. PRIORIES [Const. Art. 11.2] C. COMMANDERIES VIII MEMBERSHIIP [Const. Art. 12 as amended] 41 A. INVESTITURE B. KNIGHTS & DAMES [Const. Art. 12 & 14] C. CLERGY OF THE ORDER [Const. Art. 13] ECCLESIASTICAL COUNCIL D. SQUIRES, DEMOISELLES, DONATS, SERVING BROTHERS & SISTERS OF THE ORDER [Cont. Art. 15] IX RANKS, TITLES & AWARDS [Const. Art. 12] 50 A. RANKS B. TITLES C. AWARDS X REGALIA & INSIGNIA [Const. Art. 3] 57 A. REGALIA B. INSIGNIA RULE LOCATION PAGE RULE LOCATION PAGE ADMINISTRATIVE PROCEDURES APPENDIX 12 106 AGE LIMITS RANKS, TITLES & AWARDS 54 AIMS NAME, TRADITION 4 AMENDMENT GOVERNMENT 13 AMENDMENTS OF KKPII CONSTITUTION APPENDIX 15 115 ANNUAL REPORT FINANCE 10 ARMS OF THE ORDER REGALIA & INSIGNIA 58 ASPIRANT MEMBERSHIP 43 AUDITORS FINANCE 10 AUDIT COMMITTEE OF SOVEREIGN COUNCIL GOVERNMENT 24 AUXILIARY JUDGE GOVERNMENT 30 BADGE REGALIA & INSIGNIA 58 BAILIFF RANKS, TITLES, AWARDS 51 BAILIFF EMERITUS RANKS, TITLES, AWARDS 53 BALLOT GOVERNMENT 14 1 Page RULE LOCATION PAGE BEATITUDES MEMBERSHIP—INVESTITURE 46 BY-LAWS FOR TAX-FREE CORPORATE STATUS LEGAL STATUS 7 CAPE REGALIA & INSIGNIA 57 CERTIFICATE OF MERIT RANKS, TITLES, AWARDS 55 CHAINS OF OFFICE REGALIA, TITLES, AWARDS 58 CHAPLAIN PROVINCES OF THE ORDER 34 CHAPTER GENERAL PROVINCES OF THE ORDER 33 CHARITABLE STATUS LEGAL STATUS 7 CHARITABLE WORK PURPOSE 6 CHARTER APPENDIX 60 CHARTER OF ALLIANCE LEGAL STATUS 9 CHIVALRY NAME, TRADITION 4 CHIVALRIC ORDER VS. -

Knight's Code of Chivalry

Knight’s Code of Chivalry http://www.middle-ages.org.uk/knights-code-of-chivalry.htm The medieval knightly system had a religious, moral, and social code dating back to the Dark Ages. The Knights Code of Chivalry and the legends of King Arthur and Camelot The ideals described in the Code of Chivalry were emphasised by the oaths and vows that were sworn in the Knighthood ceremonies of the Middle Ages and Medieval era. These sacred oaths of combat were combined with the ideals of chivalry and with strict rules of etiquette and conduct. The ideals of a Knights Code of Chivalry was publicised in the poems, ballads, writings and literary works of Knights’ authors. The wandering minstrels of the Middle Ages sang these ballads and were expected to memorize the words of long poems describing the valour and the code of chivalry followed by the Medieval knights. The Dark Age myths of Arthurian Legends featuring King Arthur, Camelot and the Knights of the Round Table further strengthen the idea of a Knights’ Code of Chivalry. The Arthurian legend revolves around the Code of Chivalry which was adhered to by the Knights of the Round Table - Honour, Honesty, Valour and Loyalty. A knight was expected to have not only the strength and skills to face combat in the violent Middle Ages but was also expected to temper this aggressive side of a knight with a chivalrous side to his nature. There was not an authentic Knights’ Code of Chivalry as such - it was a moral system which went beyond rules of combat and introduced the concept of Chivalrous conduct - qualities idealized by knighthood, such as bravery, courtesy, honor, and gallantry toward women. -

The Downfall of Chivalry

Bucknell University Bucknell Digital Commons Honors Theses Student Theses Spring 2019 The oD wnfall of Chivalry: Tudor Disregard for Medieval Courtly Literature Jessica G. Downie Bucknell University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses Part of the European History Commons, and the Medieval History Commons Recommended Citation Downie, Jessica G., "The oD wnfall of Chivalry: Tudor Disregard for Medieval Courtly Literature" (2019). Honors Theses. 478. https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses/478 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses at Bucknell Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Bucknell Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. iii Acknowledgments I would first like to thank my thesis advisor, Professor Jay Goodale, for guiding me through this process. You have challenged me in many ways to become a better historian and writer, and you have always been one of my biggest fans at Bucknell. Your continuous encouragement, support, and guidance have influenced me to become the student I am today. Thank you for making me love history even more and for sharing a similar taste in music. I promise that one day I will understand how to use a semi-colon properly. Thank you to my family for always supporting me with whatever I choose to do. Without you, I would not have had the courage to pursue my interests and take on the task of writing this thesis. Thank you for your endless love and support and for never allowing me to give up. -

Chivalry and Knighthood in Medieval Europe

Hist 298: Medieval Knighthood Instructor Contact Information Instructor: Michael Furtado Office Hours: T 11- Noon, W 9 – 10 Office Location: 340V McKenzie Hall Office Telephone: 541-346-4834 Email: [email protected] (preferred contact, checked regularly) Course GTF: Kira Homo ([email protected]), Office Hours: By Appointment. Required Reading List The following titles are available for purchase at the Duckstore. Most are readily available from a variety of used sources as well. Prestwich, Michael. Knight: The Medieval Warrior’s Unofficial Manual. London: Thames & Hudson, 2010. Charny, Geoffroi de, Richard W. Kaeuper, and Elspeth Kennedy. A Knight's Own Book of Chivalry: Geoffroi De Charny. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2005. De France, Marie. The Lais of Marie de France. Trans. Glynn Burgess and Keith Busby, 2d Ed. Penguin, 1999. The Song of Roland. Trans. Dorothy Sayers. Penguin, 1957. Readings indicated with an asterisk (*) will be available as handouts or online at Canvas. Course Description Between the year 1000 and the end of the Hundred Years’ War in 1453, the role of the knight in medieval European society as warrior, defender of the faith, administrator, courtier, and even poet, changed in many significant ways. This course will introduce you to the Medieval Knight and the concept of chivalry, as well as offering some different ways of understanding the means by which the chivalric ideal influenced noble self-perception in the Middle Ages. Key topics explored in the course include the definition of the knight and his role in early medieval society, the role of the church and religion in shaping that role, the contradictions knights faced in war and peace when attempting to adhere to the “chivalric code”, and the role women played in influencing the development of particular values. -

Creation of Order of Chivalry Page 0 of 72

º Creation of Order of Chivalry Page 0 of 72 º PREFACE Knights come in many historical forms besides the traditional Knight in shining armor such as the legend of King Arthur invokes. There are the Samurai, the Mongol, the Moors, the Normans, the Templars, the Hospitaliers, the Saracens, the Teutonic, the Lakota, the Centurions just to name a very few. Likewise today the Modern Knight comes from a great variety of Cultures, Professions and Faiths. A knight was a "gentleman soldier or member of the warrior class of the Middle Ages in Europe. In other Indo-European languages, cognates of cavalier or rider French chevalier and German Ritter) suggesting a connection to the knight's mode of transport. Since antiquity a position of honor and prestige has been held by mounted warriors such as the Greek hippeus and the Roman eques, and knighthood in the Middle Ages was inextricably linked with horsemanship. Some orders of knighthood, such as the Knights Templar, have themselves become the stuff of legend; others have disappeared into obscurity. Today, a number of orders of knighthood continue to exist in several countries, such as the English Order of the Garter, the Swedish Royal Order of the Seraphim, and the Royal Norwegian Order of St. Olav. Each of these orders has its own criteria for eligibility, but knighthood is generally granted by a head of state to selected persons to recognize some meritorious achievement. In the Legion of Honor, democracy became a part of the new chivalry. No longer was this limited to men of noble birth, as in the past, who received favors from their king. -

Failures of Chivalry and Love in Chretien De Troyes

Colby College Digital Commons @ Colby Honors Theses Student Research 2014 Failures of Chivalry and Love in Chretien de Troyes Adele Priestley Colby College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/honorstheses Part of the Other English Language and Literature Commons Colby College theses are protected by copyright. They may be viewed or downloaded from this site for the purposes of research and scholarship. Reproduction or distribution for commercial purposes is prohibited without written permission of the author. Recommended Citation Priestley, Adele, "Failures of Chivalry and Love in Chretien de Troyes" (2014). Honors Theses. Paper 717. https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/honorstheses/717 This Honors Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Colby. Failures of Chivalry and Love in Chrétien de Troyes Adele Priestley Honors Thesis Fall 2013 Advisor: Megan Cook Second Reader: James Kriesel Table of Contents Introduction ………………………………………………………………… 1-18 Erec and Enide …………………………………………………………….. 19-25 Cliges ……………………………………………………………………….. 26-34 The Knight of the Cart …………………………………………………….. 35-45 The Knight with the Lion ……………………………………………….…. 46-54 The Story of the Grail …………………………………………………….. 55-63 Conclusion …………………………………………………………………. 64-67 Works Cited ……………………………………………………………….. 68-70 1 Introduction: Chrétien’s Chivalry and Courtly Love Although there are many authors to consider in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, Chrétien de Troyes stands out as a forerunner in early romances. It is commonly accepted that he wrote his stories between 1160 and 1191, which was a time period marked by a new movement of romantic literature. -

Honorary Distinctions of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg

Honorary distinctions of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg TABLE OF CONTENTS Principal Luxembourg orders 3 The Order of the Gold Lion of the House of Nassau 4 The Order of Civil and Military Merit of Adolph of Nassau 5 The Order of the Oak Crown 9 The Order of Merit of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg 12 Other orders, medals, crosses and insignia 15 Wearing of insignia 16 Return of insignia 16 Legislation 17 Honorary distinctions are an integral part of a nation’s cultural traditions. They reward individuals in recognition of outstanding personal or professional achievement, manifested in deeds or works, defending a cause for the good of the community or in specific fields. Principal Luxembourg orders The Grand Duchy of Luxembourg awards several orders, medals, crosses and insignia. Among this variety of honorary distinctions, the following four main orders of Luxembourg merit closer attention: - the Order of the Gold Lion of the House of Nassau; - the Order of Civil and Military Merit of Adolph of Nassau; - the Order of the Oak Crown; - the Order of Merit of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg. The Grand Duke is the grand master of these four orders, the highest title in the hierarchy of an order of chivalry, or of a civil or military decoration. The marshal of the court is the chancellor, the head of the chancellery, of the Order of the Gold Lion of the House of Nassau and of the Order of Civil and Military Merit of Adolph of Nassau. The Minister of State, president of the government, is the chancellor of the Order of the Oak Crown and of the Order of Merit of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg. -

New Influences on Naming Patterns in Victorian Britain Amy M

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ISU ReD: Research and eData Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData Theses and Dissertations 3-19-2016 New Influences on Naming Patterns in Victorian Britain Amy M. Hasfjord Illinois State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Hasfjord, Amy M., "New Influences on Naming Patterns in Victorian Britain" (2016). Theses and Dissertations. Paper 508. This Thesis and Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NEW INFLUENCES ON NAMING PATTERNS IN VICTORIAN BRITAIN Amy M. Hasfjord 176 Pages This thesis examines a major shift in naming patterns that occurred in Victorian Britain, roughly between 1840 and 1900, though with roots dating back to the mid-18 th century. Until approximately 1840, most new names in England that achieved wide popularity had their origins in royal and/or religious influence. The upper middle classes changed this pattern during the Victorian era by introducing a number of new names that came from popular print culture. These names are determined based on a study collecting 10,000 men’s and 10,000 women’s names from marriage announcements in the London Times. Many of these new names were inspired by the medieval revival, and that movement is treated in detail. -

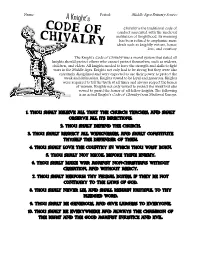

Middle Ages Primary Source Chivalry Is the Traditional Code

Name: ______________________________ Period: _____ Middle Ages Primary Source Chivalry is the traditional code of conduct associated with the medieval institution of knighthood. Its meaning has been refined to emphasize more ideals such as knightly virtues, honor, love, and courtesy. The Knight's Code of Chivalry was a moral system that stated all knights should protect others who cannot protect themselves, such as widows, children, and elders. All knights needed to have the strength and skills to fight wars in the Middle Ages. Knights not only had to be strong but they were also extremely disciplined and were expected to use their power to protect the weak and defenseless. Knights vowed to be loyal and generous. Knights were required to tell the truth at all times and always respect the honor of women. Knights not only vowed to protect the weak but also vowed to guard the honor of all fellow knights. The following is an actual Knight’s Code of Chivalry from Medieval Europe. 1. Thou shalt believe all that the Church teaches, and shalt observe all its directions. 2. Thou shalt defend the Church. 3. Thou shalt respect all weaknesses, and shalt constitute thyself the defender of them. 4. Thou shalt love the country in which thou wast born. 5. Thou shalt not recoil before thine enemy. 6. Thou shalt make war against non-Christians without cessation, and without mercy. 7. Thou shalt perform thy feudal duties, if they be not contrary to the laws of God. 8. Thou shalt never lie, and shall remain faithful to thy pledged word. -

JSP 761, Honours and Awards in the Armed Forces. Part 1

JSP 761 Honours and Awards in the Armed Forces Part 1: Directive JSP 761 Pt 1 (V5.0 Oct 16) Foreword People lie at the heart of operational capability; attracting and retaining the right numbers of capable, motivated individuals to deliver Defence outputs is critical. This is dependent upon maintaining a credible and realistic offer that earns and retains the trust of people in Defence. Part of earning and retaining that trust, and being treated fairly, is a confidence that the rules and regulations that govern our activity are relevant, current, fair and transparent. Please understand, know and use this JSP, to provide that foundation of rules and regulations that will allow that confidence to be built. JSP 761 is the authoritative guide for Honours and Awards in the Armed Services. It gives instructions on the award of Orders, Decorations and Medals and sets out the list of Honours and Awards that may be granted; detailing the nomination and recommendation procedures for each. It also provides information on the qualifying criteria for and permission to wear campaign medals, foreign medals and medals awarded by international organisations. It should be read in conjunction with Queen’s Regulations and DINs which further articulate detailed direction and specific criteria agreed by the Committee on the Grant of Honours, Decorations and Medals [Orders, Decorations and Medals (both gallantry and campaign)] or Foreign and Commonwealth Office [foreign medals and medals awarded by international organisations]. Lieutenant General Richard Nugee Chief of Defence People Defence Authority for People i JSP 761 Pt 1 (V5.0 Oct 16) Preface How to use this JSP 1.