Fordham Journal of Corporate & Financial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Global Financial Crisis and Proposed Regulatory Reform Randall D

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Brigham Young University Law School BYU Law Review Volume 2010 | Issue 2 Article 9 5-1-2010 The Global Financial Crisis and Proposed Regulatory Reform Randall D. Guynn Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/lawreview Part of the Banking and Finance Law Commons Recommended Citation Randall D. Guynn, The Global Financial Crisis and Proposed Regulatory Reform, 2010 BYU L. Rev. 421 (2010). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/lawreview/vol2010/iss2/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Brigham Young University Law Review at BYU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Law Review by an authorized editor of BYU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DO NOT DELETE 4/26/2010 8:05 PM The Global Financial Crisis and Proposed Regulatory Reform Randall D. Guynn The U.S. real estate bubble that popped in 2007 launched a sort of impersonal chevauchée1 that randomly destroyed trillions of dollars of value for nearly a year. It culminated in a worldwide financial panic during September and October of 2008.2 The most serious recession since the Great Depression followed.3 Central banks and governments throughout the world responded by flooding the markets with money and other liquidity, reducing interest rates, nationalizing or providing extraordinary assistance to major financial institutions, increasing government spending, and taking other creative steps to provide financial assistance to the markets.4 Only recently have markets begun to stabilize, but they remain fragile, like a man balancing on one leg.5 The United States and other governments have responded to the financial crisis by proposing the broadest set of regulatory reforms Partner and Head of the Financial Institutions Group, Davis Polk & Wardwell LLP, New York, New York. -

From Our Audience

Jan. 29, 2021 You can get information anywhere. Here, you get KNOWLEDGE. Vol. No. 26 -- 02 FROM OUR AUDIENCE OF GAMESTOP, “REDDIT REVOLUTIONS” AND MORE LUNACY Chris, I’m sure I’m not the only one to ask you about this. But I was wondering if you would be offering your subscribers a deeper take on what happened with $GME and /r/wallstreetbets? Besides it being interesting cocktail party conversation what’s it say about the smoke and mirrors of the market or shorts like the ones we are currently in? _______________________________________________________ At left, Thursday’s New York Post headline speaks to the “Mad” nature of markets of late; though who exactly is most mad (CRAZY) is a matter of debate! And the craziness was augmented this (Friday) morning by Tesla founder and boss Elon Musk who—merely by adding that Bitcoin hashtag to his Twitter page—caused an immediate 15% spike in that alleged “currency.” Crazy times!! Yes indeed, I’ve had a few folks asking for my take on all this silliness; among them my friend Drew Mariani at Relevant Radio, who I joined on short notice for an initial quick synopsis of all this yesterday at the end of his show (at https://relevantradio.com/2021/01/transg ender-push-in-culture/ ). We were rushed there, so I made but a few of my key points. But here, I’ll dig deeper. * Populist Peasants with Pitchforks. .or so the story goes Hey…who doesn’t like a great David vs. Goliath-type story? And that’s exactly what undergirds the unprecedented activity on Wall Street these last several trading days where a handful of heavily-shorted stocks have been concerned. -

Blackrock May Never Bring 100% of Staff to Office After Coronavirus

Login Watch TV BLACKROCK · Published 23 hours ago BlackRock may never bring 100% of staff to office after coronavirus 'I really am worried about this whole idea of culture': Fink By Jonathan Garber FOXBusiness Some bank jobs may work from home indefinitely: Report FOX Business' Charlie Gasparino says banks are telling personnel that nonessential New York City staff could be working from home well into 2021, and UBS brokers have reportedly been alerted they may not return until April 2021. BlackRock Inc. may never fully return to its pre-coronavirus routine after measures to prevent the disease's spread forced employees to work from home, according to CEO Larry Fink. It's unlikely the multitrillion-dollar asset manager's staff will ever be "100% back in oce,” Fink said Thursday at the Morningstar Investment Conference, according to CNBC. “I actually believe maybe 60% or 70%, and maybe that’s a rotation of people.” Stock Symbol BLK Stock Name BLACKROCK INC. Stock Price 558.30 Stock Change +10.24 Change % +1.87% The work-from-home environment doesn’t seem to have had much of an impact on the company’s business as employees were holding meetings via video conferencing ahead of the pandemic. The rm raked in $100 billion of assets during the three months through June, raising its total assets under management to $7.32 trillion. BlackRock is the world’s largest asset manager. Fink, however, is worried about the impact on the company’s culture. Consistently ranked as one of the best places to work, BlackRock reopened its New York oce on July 20, but said employees have the option to work remotely for the rest of the year. -

Lessons from the Financial Crisis What Have We

LESSONS FROM THE FINANCIAL CRISIS WHAT HAVE WE LEARNED? BUSINESS JOURNALISTS SPEAK OUT. Tatiana Darie Randall Smith, Project Chair PROFESSIONAL ANALYSIS ARTICLE This research project aims to explore what lessons have business journalists learned from covering the biggest story of the decade: the financial crisis. Through a series of in-depth interviews with top editors and reporters who were setting the agenda seven years ago and are leaders in the newsroom today, this study wants to investigate the following research question: How has the financial crisis changed the way business journalists do their jobs today? Seven years on, what lessons have been learned? More importantly, this study wants to assess to what extent has that knowledge translated into real changes in the industry? An answer to this question would identify what tools and indicators are journalists watching now to be able to see and avert the next financial or economic collapse. Probing theories of gatekeeping and social responsibility, this paper sets out to determine how the recession has changed the roles, duties, and constraints of business journalism. RQ: How has the financial crisis changed the way business journalists do their jobs today? Theoretical Framework Gatekeeping One of the oldest and most applicable theories in mass communication research relevant to this study is gatekeeping – a concept that describes how media organizations filter information for publication (Shoemaker & Vos, 2009). Mass audiences rely and trust journalists to scan the world’s most important events and stories into digestible snippets of information. Gatekeeping explains how and why certain stories make it out in the public while others don’t (5). -

THE INSTITUTE for QUANTITATIVE RESEARCH in FINANCE® Volume 8

® "The Q - Group" THE INSTITUTE FOR QUANTITATIVE RESEARCH ® IN FINANCE Founded 1966 -- Over 50 years of Research and Seminars Devoted to the State-of-the-Art in Investment Technology Summary of Proceedings Volume 8 2011 - 2015 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. NO PART OF THIS PUBLICATION MAY BE REPRODUCED, STORED IN A RETRIEVAL SYSTEM, OR TRANSMITTED, IN ANY FORM OR BY ANY MEANS ELECTRONIC, MECHANICAL, PHOTOCOPYING, RECORDING OR OTHERWISE, WITHOUT THE PRIOR WRITTEN PERMISSION OF THE PUBLISHER AND COPYRIGHT OWNER. Published by The Institute for Quantitative Research in Finance, P.O. Box 6194, Church Street Station, New York, NY 10249.6194 Copyright 2017 by The Institute for Quantitative Research in Finance, P.O. Box 6194, Church Street Station, New York, NY 10249.6194 Printed in The United States of America PREFACE TO VOLUME 8 iv TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE TO VOLUME 8 ........................................................................................................ iv Active Asset Management – Alpha .............................................................................................. 1 1. Cross-Firm Information Flows (Spring 2015) 1 Anna Scherbina, Bernd Schlusche 2. Dissecting Factors (Spring 2014) 2 Juhani Linnainmaa 3. The Surprising “Alpha” From Malkiel’s Monkey And Upside-Down Strategies (Fall 2013) 4 Jason Hsu 4. Will My Risk Parity Strategy Outperform? Lisa R Goldberg (Spring 2012) 5 Lisa Goldberg Active Asset Management – Mutual Fund Performance .......................................................... 7 5. Target Date Funds (Fall 2015) 7 Ned Elton, Marty Gruber 6. Patient Capital Outperformance (Spring 2015) 8 Martijn Cremers 7. Do Funds Make More When They Trade More? (Spring 2015) 10 Robert Stambaugh 8. A Sharper Ratio: A General Measure For Ranking Investment Risks (Spring 2015) 11 Kent Smetters 9. Scale And Skill In Active Management (Spring 2014) 13 Lubos Pastor 10. -

Uproar Over Unexpected Neighbors

1 BRONX TIMES REPORTER Jan. 11-17, 2013 www.bxtimes.com Jan. 11-17, 2013 www.bxtimes.com TIMES REPORTER 1 BRONX Jan. 11-17, 2013 To Advertise Call: 718-615-2520 Online: www.yournabe.com Free inside today nity classifieds s 26,29,31 Business Opps Pg 31 Instruction Pgs 27-29,31 Merchandise Pg 31 The Bronx’s p Wanted • Financing / Loans • Career Training • Garage / Yard Sales The Bronx’s elp Wanted • Business For Sale • Education Services • Merchandise Wanted elp Wanted • Misc. Business Opps • Tutoring • Merchandise For Sale • And More • And More • And More d Pg 30 Real Estate Pg 32 Services Pg 32 Automotive Pg 32 l, Commercial • Rentals • Beauty Care • Autos For Sale ntial Services • Properties For Sale • Handymen • Autos Wanted • Open Houses • Home Improvement • And More ovement • Commercial RE • And More torage • And More To Place Your Ad Call 718-615-2520 DICAL ➤ MEDICAL ➤ MEDICAL ➤ MEDICAL ➤ SALES 16 pages of Number One P WANTED HELP WANTED HELP WANTED HELP WANTED HELP WANTED Number One SALES OPPORTUNITIES Dental Assistant RN's, LPN's, BEAUTY Dist. for PAUL Dialysis Nurses/ Techs & MITCHELL, seeks exp'd, Orthodontist Office aggressive, self-motivated Psych Techs (With Exp) sales rep to service salons Work experience and references required, in Bronx. Est. territory. tification a plus. Must be highly energized, For Lincoln, Metropolitan & Kings Sal/Comm. PT, 3 days 914-921-1555 x 106 m player with positive attitude and excellent County Hospitals, Woodhull ustomer service and communication skills. Medical Center & multiple full Salary based on experience. Health, service clinics in Manhattan. -

November 2008 Issue of PJR Reports

2 NOVEMBER 2008 PJR REPORTS EDITOR’S NOTE PUBLISHED BY THE CENTER FOR MEDIA FREEDOM & RESPONSIBILITY Endorsing Candidates Melinda Quintos de Jesus Publisher HE U.S. electorate was preparing to go to the polls as this also said that 46 of the newspapers that endorsed Obama Luis V. Teodoro issue of PJR Reports was going to press. The 2008 U.S. this year supported Bush in 2004. Editor Tpresidential elections have been hailed as “historic” in While newspaper endorsements are normal during U.S. elec- that they might result (and by the time this issue is released, are tions, their absence has characterized Philippine polls since 1992, Hector Bryant L. Macale likely to have resulted) in the election of that country’s first when the first presidential elections were held after the over- Assistant Editor black president. throw of the Marcos dictatorship and its replacement by the Although racism is pretty much alive in the United States, Aquino government. JB Santos Barack Obama’s election to the U.S. presidency would suggest While many media practitioners as well as ordinary citizens Melanie Y. Pinlac that its most virulent forms have receded, although it remains don’t seem to favor it, a newspaper’s or a broadcast station’s Kathryn Roja G. Raymundo a major factor in U.S. politics. Were it not for his race, Obama endorsing candidates seems only natural of organizations en- Edsel Van DT. Dura would win (or would have won) overwhelmingly over any gaged in the dissemination and discussion of public issues. That Reporters rival from the Republican Party, given the disaster the Bush it’s not happening today in the Philippine media is mostly due Arnel Rival administration has inflicted over the last eight years on both to the latter’s belief that they have to nurture the myth that Art Director the US and the world. -

Lionel Barber's Poynter Fellowship Lecture, Yale University

Lionel Barber’s Poynter Fellowship lecture, Yale University April 21, 2009 Thank you very much for that kind introduction. It is a great honor to speak here as a Poynter fellow at Yale. Nelson Poynter’s program has done so much over the years to illuminate the theory and practice of good journalism. Though as the legendary Yogi Berra once observed, wisely: “In theory there is no difference between theory and practice. In practice, there is." These are the best of times and the worst of times to be a financial journalist. The best, because we have a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to report, analyze and comment on the most serious financial crisis since the Great Crash of 1929. The worst, because the newspaper and television industries are suffering, not only from the cyclical shock of a deep recession but also from the ongoing structural shock powered by the internet revolution. Now, out of Mr Berra’s proverbial left field, comes a third shock. The financial media find itself accused of missing the global financial crisis. Asleep at the wheel. Head in the clouds. Head in the sand. No cliché has been left unturned as reporters, commentators, yes even editors, have been castigated for failing to warn an unsuspecting public of impending disaster. Do these charges add up? Was the press an accomplice or merely an innocent bystander at the scene of the crash? To paraphrase the killer question from the Watergate hearings: What did the press know and when did it know it? Two months ago, I found myself, along with four other senior journalists from the press and television, answering a barrage of similar questions in front of the House of Commons Treasury Select committee at Westminster, the equivalent of the House Financial Services committee without the cerebral wit of Barney Frank. -

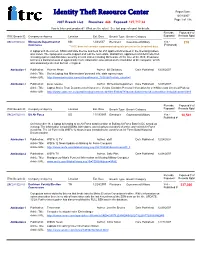

ITRC Article Database

Identity Theft Resource Center Report Date: 12/31/2007 Page 1 of 136 2007 Breach List: Breaches:446 Exposed: 127,717,24 How is this report produced? What are the rules? See last page of report for details. Records Exposed # of ITRC Breach ID Company or Agency Location Est. Date Breach Type Breach Category Exposed? Records Rptd ITRC20071231-02 Minnesota Department of MN 12/6/2007Electronic Government/Military Yes - 219 Commerce (Password) **ITRC does not consider a password adequate protection for breached data. A laptop with the names, SSNs and state license numbers for 257 applicents/licensees in the licensing system was stolen. The laptop was used to support and test the real estate, abstractors, appraisers and debt collection licensing system and data base used by several states including Minnesota. At the time of the theft, Promissor believes a limited amount of applicant/licensee information was stored on the hard drive of the computer, which was password protected, but not encrypted. Attribution 1 Publication: Pioneer PressAuthor: Bill Salisbury Date Published: 12/28/2007 Article Title: Stolen Laptop had Minnesotans' personal info, state agency says Article URL: http://www.twincities.com/allheadlines/ci_7830298?nclick_check=1 Attribution 2 Publication: press releaseAuthor: Minnesota Departmen Date Published: 12/28/2007 Article Title: Laptop Stolen From Department of Commerce Vendor Contains Personal Information for 219 Minnesota Licensed Professi Article URL: http://www.state.mn.us/portal/mn/jsp/content.do?id=-536882793&subchannel=null&sc2=null&sc3=null&contentid=5 Records Exposed # of ITRC Breach ID Company or Agency Location Est. Date Breach Type Breach Category Exposed? Records Rptd ITRC20071231-01 US Air Force US 11/19/2007Electronic Government/Military Yes - 10,501 Published # On November 18, a laptop belonging to an Air Force band member at Bolling Air Force Base in DC turned up missing. -

General Coporation Tax Allocation Percentage Report 2003

2003 General Corporation Tax Allocation Percentage Report Page - 1- @ONCE.COM INC .02 A AND J TITLE SEARCHING CO INC .01 @RADICAL.MEDIA INC 25.08 A AND L AUTO RENTAL SERVICES INC 1.00 @ROAD INC 1.47 A AND L CESSPOOL SERVICE CORP 96.51 "K" LINE AIR SERVICE U.S.A. INC 20.91 A AND L GENERAL CONTRACTORS INC 2.38 A OTTAVINO PROPERTY CORP 29.38 A AND L INDUSTRIES INC .01 A & A INDUSTRIAL SUPPLIES INC 1.40 A AND L PEN MANUFACTURING CORP 53.53 A & A MAINTENANCE ENTERPRISE INC 2.92 A AND L SEAMON INC 4.46 A & D MECHANICAL INC 64.91 A AND L SHEET METAL FABRICATIONS CORP 69.07 A & E MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS INC 77.46 A AND L TWIN REALTY INC .01 A & E PRO FLOOR AND CARPET .01 A AND M AUTO COLLISION INC .01 A & F MUSIC LTD 91.46 A AND M ROSENTHAL ENTERPRISES INC 51.42 A & H BECKER INC .01 A AND M SPORTS WEAR CORP .01 A & J REFIGERATION INC 4.09 A AND N BUSINESS SERVICES INC 46.82 A & M BRONX BAKING INC 2.40 A AND N DELIVERY SERVICE INC .01 A & M FOOD DISTRIBUTORS INC 93.00 A AND N ELECTRONICS AND JEWELRY .01 A & M LOGOS INTERNATIONAL INC 81.47 A AND N INSTALLATIONS INC .01 A & P LAUNDROMAT INC .01 A AND N PERSONAL TOUCH BILLING SERVICES INC 33.00 A & R CATERING SERVICE INC .01 A AND P COAT APRON AND LINEN SUPPLY INC 32.89 A & R ESTATE BUYERS INC 64.87 A AND R AUTO SALES INC 16.50 A & R MEAT PROVISIONS CORP .01 A AND R GROCERY AND DELI CORP .01 A & S BAGEL INC .28 A AND R MNUCHIN INC 41.05 A & S MOVING & PACKING SERVICE INC 73.95 A AND R SECURITIES CORP 62.32 A & S WHOLESALE JEWELRY CORP 78.41 A AND S FIELD SERVICES INC .01 A A A REFRIGERATION SERVICE INC 31.56 A AND S TEXTILE INC 45.00 A A COOL AIR INC 99.22 A AND T WAREHOUSE MANAGEMENT CORP 88.33 A A LINE AND WIRE CORP 70.41 A AND U DELI GROCERY INC .01 A A T COMMUNICATIONS CORP 10.08 A AND V CONTRACTING CORP 10.87 A A WEINSTEIN REALTY INC 6.67 A AND W GEMS INC 71.49 A ADLER INC 87.27 A AND W MANUFACTURING CORP 13.53 A AND A ALLIANCE MOVING INC .01 A AND X DEVELOPMENT CORP. -

The Baseline Scenario 2010-03

The Baseline Scenario 2010-03 Updated: 5-4 Update this newspaper 1 March 2010 An Underfunded Program For Greece Simon Johnson | 01 Mar 2010 By Peter Boone and Simon Johnson The EU, led by France and Germany, appears to have some sort of financing package in the works for Greece (probably still without a major role for the IMF). But the main goal seems to be to buy time – hoping for better global outcomes – rather than dealing with the issues at any more fundamental level. Greece needs 30-35bn euros to cover its funding needs for the rest of this year. But under their current fiscal plan, we are looking at something like 60bn euros in refinancing per year over the next several years – taking their debt level to 150 percent of GDP; hardly a sustainable medium-term fiscal framework. A fully credible package would need around 200bn euros, to cover three years. But the moral hazard involved in such a deal would be immense – there is no way the German government can sell that to voters (or find that much money through an off-government balance sheet operation). Alternatively, of course, the Greeks could make much more dramatic cuts to their primary deficit – the government budget balance if you take out interest payments – in order to stabilize their debt-GDP ratio. But with no significant resurgence of growth in the eurozone coming for a long time, that would really mean moving from last year’s 7.7% GDP primary deficit to around a 6% GDP primary surplus (assuming they face a real interest rate of 5%, i.e., below what they are paying today). -

April 17, 2017 Office of Regulations and Interpretations Employee

April 17, 2017 Office of Regulations and Interpretations Employee Benefits Security Administration Room N-5655 U.S. Department of Labor 200 Constitution Avenue NW, Washington, D.C. 20210 Re: RIN 1210-AB79, Fiduciary Rule Examination Ladies and Gentlemen: We are writing on behalf of the Consumer Federation of America (CFA)1 in response to the Department of Labor’s request for comment regarding its reconsideration of the conflict of interest (or “fiduciary) rule. This unjustified exercise has unnecessarily disrupted the remarkable progress financial firms have made to comply with the rule just weeks before implementation was set to begin. At best, the new legal and economic assessment will simply reinforce what we already know: that conflicts of interest are pervasive; that they exert a harmful influence on the recommendations financial advisers make to their retirement advice clients; that the retirement savings of workers and retirees are seriously eroded as a result; and that the Department acted well within its legal authority to craft a strong and workable rule to address those harms. If the Department conducts a fair review, it will inevitably conclude that the rule is working even more quickly and more dramatically than anyone could have reasonably expected to rein in the toxic conflicts that have for too long been allowed to bias retirement investment advice. Meanwhile, retirement investors will have suffered billions of dollars in harm because of this needless delay. Indeed, the evidence from the retirement plan market suggests that, if the Department erred, it did so by casting too narrow a net. If the Administration is serious about improving the ability of Americans to save for retirement, it should be looking, not to roll back this essential reform, but to expand the rule’s fiduciary protections to a broader swath of the retirement plan market.