Lessons from the Financial Crisis What Have We

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Global Financial Crisis and Proposed Regulatory Reform Randall D

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Brigham Young University Law School BYU Law Review Volume 2010 | Issue 2 Article 9 5-1-2010 The Global Financial Crisis and Proposed Regulatory Reform Randall D. Guynn Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/lawreview Part of the Banking and Finance Law Commons Recommended Citation Randall D. Guynn, The Global Financial Crisis and Proposed Regulatory Reform, 2010 BYU L. Rev. 421 (2010). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/lawreview/vol2010/iss2/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Brigham Young University Law Review at BYU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Law Review by an authorized editor of BYU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DO NOT DELETE 4/26/2010 8:05 PM The Global Financial Crisis and Proposed Regulatory Reform Randall D. Guynn The U.S. real estate bubble that popped in 2007 launched a sort of impersonal chevauchée1 that randomly destroyed trillions of dollars of value for nearly a year. It culminated in a worldwide financial panic during September and October of 2008.2 The most serious recession since the Great Depression followed.3 Central banks and governments throughout the world responded by flooding the markets with money and other liquidity, reducing interest rates, nationalizing or providing extraordinary assistance to major financial institutions, increasing government spending, and taking other creative steps to provide financial assistance to the markets.4 Only recently have markets begun to stabilize, but they remain fragile, like a man balancing on one leg.5 The United States and other governments have responded to the financial crisis by proposing the broadest set of regulatory reforms Partner and Head of the Financial Institutions Group, Davis Polk & Wardwell LLP, New York, New York. -

From Our Audience

Jan. 29, 2021 You can get information anywhere. Here, you get KNOWLEDGE. Vol. No. 26 -- 02 FROM OUR AUDIENCE OF GAMESTOP, “REDDIT REVOLUTIONS” AND MORE LUNACY Chris, I’m sure I’m not the only one to ask you about this. But I was wondering if you would be offering your subscribers a deeper take on what happened with $GME and /r/wallstreetbets? Besides it being interesting cocktail party conversation what’s it say about the smoke and mirrors of the market or shorts like the ones we are currently in? _______________________________________________________ At left, Thursday’s New York Post headline speaks to the “Mad” nature of markets of late; though who exactly is most mad (CRAZY) is a matter of debate! And the craziness was augmented this (Friday) morning by Tesla founder and boss Elon Musk who—merely by adding that Bitcoin hashtag to his Twitter page—caused an immediate 15% spike in that alleged “currency.” Crazy times!! Yes indeed, I’ve had a few folks asking for my take on all this silliness; among them my friend Drew Mariani at Relevant Radio, who I joined on short notice for an initial quick synopsis of all this yesterday at the end of his show (at https://relevantradio.com/2021/01/transg ender-push-in-culture/ ). We were rushed there, so I made but a few of my key points. But here, I’ll dig deeper. * Populist Peasants with Pitchforks. .or so the story goes Hey…who doesn’t like a great David vs. Goliath-type story? And that’s exactly what undergirds the unprecedented activity on Wall Street these last several trading days where a handful of heavily-shorted stocks have been concerned. -

Blackrock May Never Bring 100% of Staff to Office After Coronavirus

Login Watch TV BLACKROCK · Published 23 hours ago BlackRock may never bring 100% of staff to office after coronavirus 'I really am worried about this whole idea of culture': Fink By Jonathan Garber FOXBusiness Some bank jobs may work from home indefinitely: Report FOX Business' Charlie Gasparino says banks are telling personnel that nonessential New York City staff could be working from home well into 2021, and UBS brokers have reportedly been alerted they may not return until April 2021. BlackRock Inc. may never fully return to its pre-coronavirus routine after measures to prevent the disease's spread forced employees to work from home, according to CEO Larry Fink. It's unlikely the multitrillion-dollar asset manager's staff will ever be "100% back in oce,” Fink said Thursday at the Morningstar Investment Conference, according to CNBC. “I actually believe maybe 60% or 70%, and maybe that’s a rotation of people.” Stock Symbol BLK Stock Name BLACKROCK INC. Stock Price 558.30 Stock Change +10.24 Change % +1.87% The work-from-home environment doesn’t seem to have had much of an impact on the company’s business as employees were holding meetings via video conferencing ahead of the pandemic. The rm raked in $100 billion of assets during the three months through June, raising its total assets under management to $7.32 trillion. BlackRock is the world’s largest asset manager. Fink, however, is worried about the impact on the company’s culture. Consistently ranked as one of the best places to work, BlackRock reopened its New York oce on July 20, but said employees have the option to work remotely for the rest of the year. -

A Single Organization Controls Almost Everything You See, Hear, and Read in the Media and They've Been Handpicking Your Leaders for Decades

by Matt Agorist January 29, 2018 from TheFreeThoughtProject Website A single organization controls almost everything you see, hear, and read in the media and they've been handpicking your leaders for decades. It is no secret that over the last 4 decades, mainstream media has been consolidated from dozens of competing companies to only six. Hundreds of channels, websites, news outlets, newspapers, and magazines, making up ninety percent of all media is controlled by very few people, giving Americans the illusion of choice. While six companies controlling most everything the Western world consumes in regard to media may sound like a sinister arrangement, the Swiss Propaganda Research center (SPR) has just released information that is even worse. The research group was able to tie all these media companies to a single organization: the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR). For those who may be unaware, the CFR is a primary member of the circle of Washington think-tanks promoting endless war. As former Army Major Todd Pierce describes, this group acts as "primary provocateurs" using, "'psychological suggestiveness' to create a false narrative of danger from some foreign entity with the objective being to create paranoia within the U.S. population that it is under imminent threat of attack or takeover." A senior member of the CFR and outspoken neocon warmonger, Robert Kagan has even publicly proclaimed that the U.S. should create an empire. The narrative created by CFR and its cohorts is picked up by their secondary communicators, also known the mainstream media, who push it on the populace with no analysis or questioning. -

THE INSTITUTE for QUANTITATIVE RESEARCH in FINANCE® Volume 8

® "The Q - Group" THE INSTITUTE FOR QUANTITATIVE RESEARCH ® IN FINANCE Founded 1966 -- Over 50 years of Research and Seminars Devoted to the State-of-the-Art in Investment Technology Summary of Proceedings Volume 8 2011 - 2015 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. NO PART OF THIS PUBLICATION MAY BE REPRODUCED, STORED IN A RETRIEVAL SYSTEM, OR TRANSMITTED, IN ANY FORM OR BY ANY MEANS ELECTRONIC, MECHANICAL, PHOTOCOPYING, RECORDING OR OTHERWISE, WITHOUT THE PRIOR WRITTEN PERMISSION OF THE PUBLISHER AND COPYRIGHT OWNER. Published by The Institute for Quantitative Research in Finance, P.O. Box 6194, Church Street Station, New York, NY 10249.6194 Copyright 2017 by The Institute for Quantitative Research in Finance, P.O. Box 6194, Church Street Station, New York, NY 10249.6194 Printed in The United States of America PREFACE TO VOLUME 8 iv TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE TO VOLUME 8 ........................................................................................................ iv Active Asset Management – Alpha .............................................................................................. 1 1. Cross-Firm Information Flows (Spring 2015) 1 Anna Scherbina, Bernd Schlusche 2. Dissecting Factors (Spring 2014) 2 Juhani Linnainmaa 3. The Surprising “Alpha” From Malkiel’s Monkey And Upside-Down Strategies (Fall 2013) 4 Jason Hsu 4. Will My Risk Parity Strategy Outperform? Lisa R Goldberg (Spring 2012) 5 Lisa Goldberg Active Asset Management – Mutual Fund Performance .......................................................... 7 5. Target Date Funds (Fall 2015) 7 Ned Elton, Marty Gruber 6. Patient Capital Outperformance (Spring 2015) 8 Martijn Cremers 7. Do Funds Make More When They Trade More? (Spring 2015) 10 Robert Stambaugh 8. A Sharper Ratio: A General Measure For Ranking Investment Risks (Spring 2015) 11 Kent Smetters 9. Scale And Skill In Active Management (Spring 2014) 13 Lubos Pastor 10. -

Top of Page Interview Information--Different Title

Oral History Center, The Bancroft Library, University of California Berkeley Oral History Center University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California Paul Steiger Paul Steiger: Business Reporting and the Creation of ProPublica The Marion and Herbert Sandler Oral History Project Interviews conducted by Martin Meeker in 2017 Copyright © 2019 by The Regents of the University of California Oral History Center, The Bancroft Library, University of California Berkeley ii Since 1954 the Oral History Center of the Bancroft Library, formerly the Regional Oral History Office, has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West, and the nation. Oral History is a method of collecting historical information through tape-recorded interviews between a narrator with firsthand knowledge of historically significant events and a well-informed interviewer, with the goal of preserving substantive additions to the historical record. The tape recording is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The corrected manuscript is bound with photographs and illustrative materials and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and in other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. ********************************* All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between The Regents of the University of California and Paul Steiger dated November 29, 2017. -

Uproar Over Unexpected Neighbors

1 BRONX TIMES REPORTER Jan. 11-17, 2013 www.bxtimes.com Jan. 11-17, 2013 www.bxtimes.com TIMES REPORTER 1 BRONX Jan. 11-17, 2013 To Advertise Call: 718-615-2520 Online: www.yournabe.com Free inside today nity classifieds s 26,29,31 Business Opps Pg 31 Instruction Pgs 27-29,31 Merchandise Pg 31 The Bronx’s p Wanted • Financing / Loans • Career Training • Garage / Yard Sales The Bronx’s elp Wanted • Business For Sale • Education Services • Merchandise Wanted elp Wanted • Misc. Business Opps • Tutoring • Merchandise For Sale • And More • And More • And More d Pg 30 Real Estate Pg 32 Services Pg 32 Automotive Pg 32 l, Commercial • Rentals • Beauty Care • Autos For Sale ntial Services • Properties For Sale • Handymen • Autos Wanted • Open Houses • Home Improvement • And More ovement • Commercial RE • And More torage • And More To Place Your Ad Call 718-615-2520 DICAL ➤ MEDICAL ➤ MEDICAL ➤ MEDICAL ➤ SALES 16 pages of Number One P WANTED HELP WANTED HELP WANTED HELP WANTED HELP WANTED Number One SALES OPPORTUNITIES Dental Assistant RN's, LPN's, BEAUTY Dist. for PAUL Dialysis Nurses/ Techs & MITCHELL, seeks exp'd, Orthodontist Office aggressive, self-motivated Psych Techs (With Exp) sales rep to service salons Work experience and references required, in Bronx. Est. territory. tification a plus. Must be highly energized, For Lincoln, Metropolitan & Kings Sal/Comm. PT, 3 days 914-921-1555 x 106 m player with positive attitude and excellent County Hospitals, Woodhull ustomer service and communication skills. Medical Center & multiple full Salary based on experience. Health, service clinics in Manhattan. -

November 2008 Issue of PJR Reports

2 NOVEMBER 2008 PJR REPORTS EDITOR’S NOTE PUBLISHED BY THE CENTER FOR MEDIA FREEDOM & RESPONSIBILITY Endorsing Candidates Melinda Quintos de Jesus Publisher HE U.S. electorate was preparing to go to the polls as this also said that 46 of the newspapers that endorsed Obama Luis V. Teodoro issue of PJR Reports was going to press. The 2008 U.S. this year supported Bush in 2004. Editor Tpresidential elections have been hailed as “historic” in While newspaper endorsements are normal during U.S. elec- that they might result (and by the time this issue is released, are tions, their absence has characterized Philippine polls since 1992, Hector Bryant L. Macale likely to have resulted) in the election of that country’s first when the first presidential elections were held after the over- Assistant Editor black president. throw of the Marcos dictatorship and its replacement by the Although racism is pretty much alive in the United States, Aquino government. JB Santos Barack Obama’s election to the U.S. presidency would suggest While many media practitioners as well as ordinary citizens Melanie Y. Pinlac that its most virulent forms have receded, although it remains don’t seem to favor it, a newspaper’s or a broadcast station’s Kathryn Roja G. Raymundo a major factor in U.S. politics. Were it not for his race, Obama endorsing candidates seems only natural of organizations en- Edsel Van DT. Dura would win (or would have won) overwhelmingly over any gaged in the dissemination and discussion of public issues. That Reporters rival from the Republican Party, given the disaster the Bush it’s not happening today in the Philippine media is mostly due Arnel Rival administration has inflicted over the last eight years on both to the latter’s belief that they have to nurture the myth that Art Director the US and the world. -

Lionel Barber's Poynter Fellowship Lecture, Yale University

Lionel Barber’s Poynter Fellowship lecture, Yale University April 21, 2009 Thank you very much for that kind introduction. It is a great honor to speak here as a Poynter fellow at Yale. Nelson Poynter’s program has done so much over the years to illuminate the theory and practice of good journalism. Though as the legendary Yogi Berra once observed, wisely: “In theory there is no difference between theory and practice. In practice, there is." These are the best of times and the worst of times to be a financial journalist. The best, because we have a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to report, analyze and comment on the most serious financial crisis since the Great Crash of 1929. The worst, because the newspaper and television industries are suffering, not only from the cyclical shock of a deep recession but also from the ongoing structural shock powered by the internet revolution. Now, out of Mr Berra’s proverbial left field, comes a third shock. The financial media find itself accused of missing the global financial crisis. Asleep at the wheel. Head in the clouds. Head in the sand. No cliché has been left unturned as reporters, commentators, yes even editors, have been castigated for failing to warn an unsuspecting public of impending disaster. Do these charges add up? Was the press an accomplice or merely an innocent bystander at the scene of the crash? To paraphrase the killer question from the Watergate hearings: What did the press know and when did it know it? Two months ago, I found myself, along with four other senior journalists from the press and television, answering a barrage of similar questions in front of the House of Commons Treasury Select committee at Westminster, the equivalent of the House Financial Services committee without the cerebral wit of Barney Frank. -

The Trump Administration and the Media: Attacks on Press Credibility Endanger US Democracy and Global Press Freedom

The Trump Administration and the Media: Attacks on press credibility endanger US democracy and global press freedom By Leonard Downie Jr. with research by Stephanie Sugars A special report of the Committee to Protect Journalists The Trump Administration and the Media: Attacks on press credibility endanger US democracy and global press freedom By Leonard Downie Jr. with research by Stephanie Sugars A special report of the Committee to Protect Journalists The Committee to Protect Journalists is an independent, nonprofit organization that promotes press freedom worldwide. We defend the right of journalists to report the news safely and without fear of reprisal. In order to preserve our independence, CPJ does not accept any government grants or support of any kind; our work is funded entirely by contributions from individuals, foundations, and corporations. CHAIR VICE CHAIR HONORARY CHAIRMAN EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Kathleen Carroll Jacob Weisberg Terry Anderson Joel Simon DIRECTORS Jonathan Klein Norman Pearlstine getty images los angeles times Stephen J. Adler reuters Jane Kramer Lydia Polgreen the new yorker gimlet media Andrew Alexander Mhamed Krichen Ahmed Rashid al-jazeera Amanda Bennett David Remnick Isaac Lee Krishna Bharat the new yorker google Rebecca MacKinnon Maria Teresa Ronderos Diane Brayton Kati Marton Alan Rusbridger new york times company lady margaret hall, oxford Michael Massing Susan Chira Karen Amanda Toulon Geraldine Fabrikant Metz the marshall project bloomberg news the new york times Sheila Coronel Darren Walker columbia university Matt Murray ford foundation school of journalism the wall street journal and dow jones newswires Roger Widmann Anne Garrels Victor Navasky Jon Williams Cheryl Gould the nation rté Lester Holt Clarence Page Matthew Winkler nbc chicago tribune bloomberg news SENIOR ADVISERS David Marash Sandra Mims Rowe Christiane Amanpour Charles L. -

Penelope Abernathy Joaquin Alvarado

How Will Journalism Survive the Internet Age? bios Penelope Abernathy Joaquin Alvarado Penelope Abernathy is Knight Chair in Journalism Joaquin Alvarado is Senior Vice President, Digital and Digital Media Economics at the University Innovation at American Public Media. Alvarado of North Carolina School of Journalism and leads strategic development of APM’s Public Mass Communication. Abernathy, a journalism Insight initiatives, as well as developing models for professional with more than 30 years experience deepening audience engagement, widening digital as a reporter, editor and media executive, became reach and increasing digital revenue growth across all the Knight Chair in Journalism and Digital Media operating divisions. Economics at the school July 1, 2008. Abernathy, a Laurinburg, N.C., native and former executive Alvarado comes to APM/MPR from the Corporation at the Wall Street Journal and the New York Times, for Public Broadcasting, where he led successful specializes in preserving quality journalism by initiatives in broadening the reach and diversity helping the news business succeed economically in within public media as Senior Vice President for the digital media environment. Before joining the Diversity and Innovation. Prior to joining the school, she was vice president and executive director CPB, Alvarado spearheaded many key projects and of industry programs at the Paley Center for Media companies furthering new frameworks for public in New York City. As an executive, Abernathy media, education and community leadership in the launched new enterprises and helped increase Internet age. In 2008, he initiated CoCo Studios, revenue at some of the nation’s most prominent news promoting media collaboration and information organizations and publishing companies, including sharing for fiber and mobile networks. -

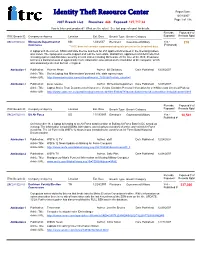

ITRC Article Database

Identity Theft Resource Center Report Date: 12/31/2007 Page 1 of 136 2007 Breach List: Breaches:446 Exposed: 127,717,24 How is this report produced? What are the rules? See last page of report for details. Records Exposed # of ITRC Breach ID Company or Agency Location Est. Date Breach Type Breach Category Exposed? Records Rptd ITRC20071231-02 Minnesota Department of MN 12/6/2007Electronic Government/Military Yes - 219 Commerce (Password) **ITRC does not consider a password adequate protection for breached data. A laptop with the names, SSNs and state license numbers for 257 applicents/licensees in the licensing system was stolen. The laptop was used to support and test the real estate, abstractors, appraisers and debt collection licensing system and data base used by several states including Minnesota. At the time of the theft, Promissor believes a limited amount of applicant/licensee information was stored on the hard drive of the computer, which was password protected, but not encrypted. Attribution 1 Publication: Pioneer PressAuthor: Bill Salisbury Date Published: 12/28/2007 Article Title: Stolen Laptop had Minnesotans' personal info, state agency says Article URL: http://www.twincities.com/allheadlines/ci_7830298?nclick_check=1 Attribution 2 Publication: press releaseAuthor: Minnesota Departmen Date Published: 12/28/2007 Article Title: Laptop Stolen From Department of Commerce Vendor Contains Personal Information for 219 Minnesota Licensed Professi Article URL: http://www.state.mn.us/portal/mn/jsp/content.do?id=-536882793&subchannel=null&sc2=null&sc3=null&contentid=5 Records Exposed # of ITRC Breach ID Company or Agency Location Est. Date Breach Type Breach Category Exposed? Records Rptd ITRC20071231-01 US Air Force US 11/19/2007Electronic Government/Military Yes - 10,501 Published # On November 18, a laptop belonging to an Air Force band member at Bolling Air Force Base in DC turned up missing.