Internal Audit Technology Risk Business Risk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ordinance No. 2015-37

ORDINANCE NO. 2015-37 ORDINANCE GRANTING AN EXCLUSIVE FRANCHISE TO PROGRESSIVE WASTE SOLUTIONS OF FL., INC., A FLORIDA CORPORATION, FOR THE COLLECTION OF RESIDENTIAL MUNICIPAL SOLID WASTE, AS THE COMPANY WITH THE HIGHEST RANKED BEST OVERALL PROPOSAL PURSUANT TO REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL NO. 2014-15-9500-00-002, FOR A TERM BEGINNING UPON EXECUTION OF THE EXCLUSIVE FRANCHISE AGREEMENT BY THE PARTIES AND ENDING ON SEPTEMBER 30, 2019, WITH AN AUTOMATIC RENEWAL TERM THEREAFTER OF FIVE YEARS, BEGINNING ON OCTOBER 1, 2019 AND ENDING ON SEPTEMBER 30, 2023, AND SUBSEQUENT RENEWALS AT THE OPTION OF THE PARTIES, FOR A TERM OF ONE YEAR EACH, WITH A CUMULATIVE DURATION OF ALL SUBSEQUENT RENEWALS AFTER THE FIRST RENEWAL TERM NOT EXCEEDING A TOTAL OF FIVE YEARS; APPROVING THE TERMS OF THE EXCLUSIVE FRANCHISE IN SUBSTANTIAL CONFORMITY WITH THE AGREEMENT ATTACHED HERETO AND MADE A PART HEREOF AS EXHIBIT '·t··; AND AUTHORIZING THE MAYOR AND THE CITY CLERK, AS ATTESTING WITNESS, ON BEHALF OF THE CITY, TO EXECUTE THE EXCLUSIVE FRANCHISE AGREEMENT; REPEALING ALL ORDINANCES OR PARTS OF ORDINANCES IN CONFLICT HEREWITH; PROVIDING PENALTIES FOR VIOLATION HEREOF; PROVIDING FOR A SEVERABILITY CLAUSE; AND PROVIDING FOR AN EFFECTIVE DATE. WHEREAS, the City issued a request for proposals ("'RFP") for certain types of Solid Waste Collection Services; and ORDINANCE NO. 2015-37 Page 2 WHEREAS, Progressive Waste Solutions of FL, Inc. ("'Progressive Waste") submitted a proposal in response to the City's RFP (RFP No. 2014-15-9500-00-002); and WHEREAS, the City has relied upon -

Super! Drama TV April 2021

Super! drama TV April 2021 Note: #=serial number [J]=in Japanese 2021.03.29 2021.03.30 2021.03.31 2021.04.01 2021.04.02 2021.04.03 2021.04.04 Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun 06:00 06:00 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:00 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:00 06:00 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:00 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:00 #15 #17 #19 #21 「The Long Morrow」 「Number 12 Looks Just Like You」 「Night Call」 「Spur of the Moment」 06:30 06:30 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 #16 06:30 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:30 06:30 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:30 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:30 「The Self-Improvement of Salvadore #18 #20 #22 Ross」 「Black Leather Jackets」 「From Agnes - With Love」 「Queen of the Nile」 07:00 07:00 CRIMINAL MINDS Season 10 07:00 CRIMINAL MINDS Season 10 07:00 07:00 STAR TREK Season 1 07:00 THUNDERBIRDS 07:00 #1 #2 #20 #19 「X」 「Burn」 「Court Martial」 「DANGER AT OCEAN DEEP」 07:30 07:30 07:30 08:00 08:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:00 08:00 ULTRAMAN towards the future 08:00 THUNDERBIRDS 08:00 10 10 #1 #20 #13「The Romance Recalibration」 #15「The Locomotion Reverberation」 「bitter harvest」 「MOVE- AND YOU'RE DEAD」 08:30 08:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:30 08:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:30 10 #14「The Emotion Detection 10 12 Automation」 #16「The Allowance Evaporation」 #6「The Imitation Perturbation」 09:00 09:00 information[J] 09:00 information[J] 09:00 09:00 information[J] 09:00 information[J] 09:00 09:30 09:30 THE GREAT 09:30 SUPERNATURAL Season 14 09:30 09:30 BETTER CALL SAUL Season 3 09:30 ZOEY’S EXTRAORDINARY -

Super! Drama TV December 2020 ▶Programs Are Suspended for Equipment Maintenance from 1:00-7:00 on the 15Th

Super! drama TV December 2020 ▶Programs are suspended for equipment maintenance from 1:00-7:00 on the 15th. Note: #=serial number [J]=in Japanese [D]=in Danish 2020.11.30 2020.12.01 2020.12.02 2020.12.03 2020.12.04 2020.12.05 2020.12.06 Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun 06:00 06:00 MACGYVER Season 2 06:00 MACGYVER Season 2 06:00 MACGYVER Season 2 06:00 MACGYVER Season 2 06:00 06:00 MACGYVER Season 3 06:00 BELOW THE SURFACE 06:00 #20 #21 #22 #23 #1 #8 [D] 「Skyscraper - Power」 「Wind + Water」 「UFO + Area 51」 「MacGyver + MacGyver」 「Improvise」 06:30 06:30 06:30 07:00 07:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:00 07:00 STAR TREK Season 1 07:00 STAR TREK: THE NEXT 07:00 Season 12 Season 12 Season 12 Season 12 #4 GENERATION Season 7 #7「The Grant Allocation Derivation」 #9 「The Citation Negation」 #11「The Paintball Scattering」 #13「The Confirmation Polarization」 「The Naked Time」 #15 07:30 07:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:30 information [J] 07:30 「LOWER DECKS」 07:30 Season 12 Season 12 Season 12 #8「The Consummation Deviation」 #10「The VCR Illumination」 #12「The Propagation Proposition」 08:00 08:00 SUPERNATURAL Season 11 08:00 SUPERNATURAL Season 11 08:00 SUPERNATURAL Season 11 08:00 SUPERNATURAL Season 11 08:00 08:00 THUNDERBIRDS ARE GO 08:00 STAR TREK: THE NEXT 08:00 #5 #6 #7 #8 Season 3 GENERATION Season 7 「Thin Lizzie」 「Our Little World」 「Plush」 「Just My Imagination」 #18「AVALANCHE」 #16 08:30 08:30 08:30 THUNDERBIRDS ARE GO 「THINE OWN SELF」 08:30 -

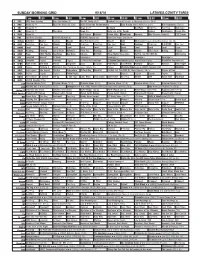

Sunday Morning Grid 9/18/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 9/18/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Cincinnati Bengals at Pittsburgh Steelers. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) (TVG) 2016 Evian Golf Championship Auto Racing Global RallyCross Series. Rio Paralympics (Taped) 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch BestPan! Paid Prog. Paid Prog. Skin Care 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) Vista L.A. at the Parade Explore Jack Hanna Ocean Mys. 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Amazing Why Pressure Cooker? CIZE Dance 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Good Day Game Day (N) Å 13 MyNet Arthritis? Matter Secrets Beauty Best Pan Ever! (TVG) Bissell AAA MLS Soccer Galaxy at Sporting Kansas City. (N) 18 KSCI Paid Prog. Paid Prog. Church Faith Paid Prog. Paid Prog. Paid Prog. AAA Cooking! Paid Prog. R.COPPER Paid Prog. 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR Painting Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexico Martha Ellie’s Real Baking Project 28 KCET Peep 1001 Nights Bug Bites Bug Bites Edisons Biz Kid$ Three Nights Three Days Eat Fat, Get Thin With Dr. ADD-Loving 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión Pagado Secretos Pagado La Rosa de Guadalupe El Coyote Emplumado (1983) María Elena Velasco. -

NCIS Comments on RMA's Second Draft of the 2011 SRA And

Response to the Risk Management Agency’s Second Draft of the Standard Reinsurance Agreement and Appendices Issued on February 23, 2010 Submitted by National Crop Insurance Services, Inc. On April 9, 2010 National Crop Insurance Services, Inc. 8900 Indian Creek Parkway, Suite 600 Overland Park, KS 66210-1567 National Crop Insurance Services, Inc. April 9, 2010 Contents Part Page 1. Overview……………………………………………………….. 3 2. Concerns with the Financial Provisions of the Second Draft.. 3 3. SRA Provisions………………………………………………… 26 National Crop Insurance Services, Inc. 2 April 9, 2010 1. Overview NCIS appreciates the ongoing efforts of USDA’s Risk Management Agency (RMA) to meet and discuss its second draft of the 2011 Standard Reinsurance Agreement (SRA) and the appendices. The industry continues to have serious problems with the second draft. With these comments, which include a new proposal for reinsurance terms of the SRA, and the negotiating meetings scheduled to take place soon, NCIS believes that a workable and mutually acceptable SRA and appendices can be developed. On February 17, 2010, RMA officials presented the key features of the financial provisions of the second draft of the SRA at the crop insurance industry’s annual meeting. On February 23, 2010, RMA released the text of the second draft, including the texts of draft Appendices I-IV, and requested comments by March 22, 2010 (Manager’s Bulletin No. MGR-10-002). On March 19, 2010, RMA extended the comment period to April 9, 2010 (Manager’s Bulletin No. MGR- 10-002.1). These comments are being provided in response to the April 9 call for comments on April 9. -

Solicitation Specifically Said That TEIS IV

1. This Contract Is A Rated Order Under Rating Page of Pages SOLICITATION, OFFER AND AWARD DPAS (15 CFR 700) DOA7 1 142 2. Contract Number 3. Solicitation Number 4. Type of Solicitation 5. Date Issued 6. Requisition/Purchase Number W9128Z-20-R-0001 Sealed Bid (IFB) 2019NOV20 SEE SCHEDULE X Negotiated (RFP) 7. Issued By Code W9128Z 8. Address Offer To (If Other Than Item 7) ACC-APG HUACHUCA DIVISION CCAP-CCH 2133 CUSHING STREET FORT HUACHUCA, AZ 85613-1190 NOTE: In sealed bid solicitations ‘offer’ and ‘offeror’ mean ‘bid’ and ‘bidder’. SOLICITATION 9. Sealed offers in original and copies for furnishing the supplies or services in the Schedule will be received at the place specified in item 8, or if handcarried, in the depository located in until 04:00pm (hour) local time 2019DEC30 (Date). Caution - Late Submissions, Modifications, and Withdrawals: See Section L, Provision No. 52.214-7 or 52.215-1. All offers are subject to all terms and conditions contained in this solicitation. 10. For Information A. Name B. Telephone (No Collect Calls) C. E-mail Address Call: ADELINA KOSTUR Area Code Number Ext. [email protected] (520)538-6404 11. Table Of Contents (X) Sec. Description Page(s) (X) Sec. Description Page(s) Part I - The Schedule Part II - Contract Clauses X A Solicitation/Contract Form 1 X I Contract Clauses 47 X B Supplies or Services and Prices/Costs 4 Part III - List Of Documents, Exhibits, And Other Attach. X C Description/Specs./Work Statement 10 X J List of Attachments 108 X D Packaging and Marking 11 Part IV - Representations And Instructions X E Inspection and Acceptance 13 K Representations, Certifications, and X 110 X F Deliveries or Performance 14 Other Statements of Offerors X G Contract Administration Data 19 X L Instrs., Conds., and Notices to Offerors 119 X H Special Contract Requirements 23 X M Evaluation Factors for Award 136 OFFER (Must be fully completed by offeror) NOTE: Item 12 does not apply if the solicitation includes the provisions at 52.214-16, Minimum Bid Acceptance Period. -

Naval Criminal Investigative Service (NCIS), (B)(6), (B)(7)(C) (B)(6), (B)(7)(C) NCIS (Report No

INSPECTOR GENERAL DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE 4800 MARK CENTER DRIVE ALEXANDRIA, VIRGINIA 22350-1500 MAR 2 5 2013 MEMORANDUM FOR PRINCIPAL DEPUTY INSPECTOR GENERAL SUBJECT: Report oflnvestigation - (b)(6), (b)(7)(C) (b)(6), (b)(7)(C)Naval Criminal Investigative Service (NCIS), (b)(6), (b)(7)(C) (b)(6), (b)(7)(C) NCIS (Report No. 20121205-003105) We recently completed an investigation to address allegations that, (b)(6), (b)(7)(C) (b)(6), (b)(7)(C) NCIS, (b)(6), (b)(7)(C) mismanaged the NCIS mobility program, including improper management directed transfers, and wasted Government resources in implementing the program. We did not substantiate the allegations. We found that (b)(6), (b)(7)(C) (b)(6), (b)(7)(C) conveyed to the Secretary of the Navy (b)(6),detailed (b)(7)(C) vision for using the NCIS mobility program to improve mission effectiveness. We found that (b)(6), (b)(7)(C) directed (b)(6), (b)(7)(C)to implement the mobility program consistent with that vision, and that (b)(6), (b)(7)(C) did so. We found that total employee transfers, including management directed transfers, increased substantially in Fiscal Year 2012. However, we also found that the average transfer cost for management directed transfers was substantially less than transfer costs for voluntary transfers. We evaluated our findings against DoD, Department of the Navy, and NCIS regulations governing mobility programs for civilian employees, as well as against the Joint Ethics Regulations. We determined (b)(6), (b)(7)(C) decisions were consistent with regulation and the expenditure of Government resources in implementing the mobility program was not extravagant, careless, or needless. -

Walpole Public Library DVD List A

Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] Last updated: 9/17/2021 INDEX Note: List does not reflect items lost or removed from collection A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Nonfiction A A A place in the sun AAL Aaltra AAR Aardvark The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.1 vol.1 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.2 vol.2 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.3 vol.3 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.4 vol.4 ABE Aberdeen ABO About a boy ABO About Elly ABO About Schmidt ABO About time ABO Above the rim ABR Abraham Lincoln vampire hunter ABS Absolutely anything ABS Absolutely fabulous : the movie ACC Acceptable risk ACC Accepted ACC Accountant, The ACC SER. Accused : series 1 & 2 1 & 2 ACE Ace in the hole ACE Ace Ventura pet detective ACR Across the universe ACT Act of valor ACT Acts of vengeance ADA Adam's apples ADA Adams chronicles, The ADA Adam ADA Adam’s Rib ADA Adaptation ADA Ad Astra ADJ Adjustment Bureau, The *does not reflect missing materials or those being mended Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] ADM Admission ADO Adopt a highway ADR Adrift ADU Adult world ADV Adventure of Sherlock Holmes’ smarter brother, The ADV The adventures of Baron Munchausen ADV Adverse AEO Aeon Flux AFF SEAS.1 Affair, The : season 1 AFF SEAS.2 Affair, The : season 2 AFF SEAS.3 Affair, The : season 3 AFF SEAS.4 Affair, The : season 4 AFF SEAS.5 Affair, -

Robust Normalization of Next Generation Sequencing Data

Robust Normalization of Next Generation Sequencing Data Dissertation zur Erlangung des Grades eines Doktors der Naturwissenschaften (Dr. rer. nat.) am Fachbereich Mathematik und Informatik der Freien Universität Berlin vorgelegt von Johannes Helmuth Berlin, 2017 Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Martin Vingron Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Uwe Ohler Tag der Disputation: 15.05.2017 Preface This dissertation introduces a robust normalization method to uncover signals in noisy next generation sequencing data. The genesis of the described approach is the observation that next generation sequencing resembles a sampling process that can be modeled by means of discrete statistics. The specic and sensitive detection of signals from sequencing data pushes the eld of molecular biology forward towards a comprehensive understanding of the functional basic unit of life – the cell. The thesis is structured in three parts: Part I provides a background on molecular biology and statistics that is needed to understand Part II. I describe the fascinating subject of gene regulation and how diverse next genera- tion sequencing techniques have been developed to study cellular processes at the molec- ular level. The data generated in these experiments are naturally modeled with statistical models. To accurately quantify sequencing data, I propose the computational program “bamsignals” which was developed in collaboration with Alessandro Mammana [1]. Part II introduces a novel sequencing data normalization method which was developed under supervision of Dr. Ho-Ryun Chung from the Epigenomics laboratory at the Max Planck Institute for Molecular Genetics in Berlin. A manuscript describing the approach is de- posited on bioRxiv [2] and the method was also featured as a journal article in Springer Press BioSpektrum [3]. -

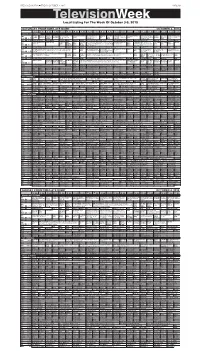

Televisionweek Local Listing for the Week of October 3-9, 2015

PRESS & DAKOTAN n FRIDAY, OCTOBER 2, 2015 PAGE 9B TelevisionWeek Local Listing For The Week Of October 3-9, 2015 SATURDAY PRIMETIME/LATE NIGHT OCTOBER 3, 2015 3:00 3:30 4:00 4:30 5:00 5:30 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 12:00 12:30 1:00 1:30 BROADCAST STATIONS Cook’s Victory Prairie America’s Classic Gospel “Red The Lawrence Welk Doc Martin Martin Keeping As Time Father Brown A for- No Cover, No Mini- Austin City Limits Under- Sun Stu- Globe Trekker Park PBS Country Garden’s Yard and Heartlnd Rocks Homecom- Show finds out Louisa is Up Goes mer POW is suspected mum Å Hall of Fame Induction ground dio Ses- Güell; Casa Batlló. Å KUSD ^ 8 ^ Å Garden ing” Å pregnant. Å By Å of murder. Ceremony. (N) sions (DVS) KTIV $ 4 $ Action Sports (N) Horse Racing Preview News News 4 Insider ›› “Live From New York!” (2015) Saturday Night Live News 4 Saturday Night Live Å Extra (N) Å 1st Look House Action Sports (N) (In Horse Racing Paid Pro- NBC KDLT The Big ›› “Live From New York!” (2015) Premiere. Saturday Night Live KDLT Saturday Night Live (Season The Simp- The Simp- KDLT (Off Air) NBC Stereo) Å gram Nightly News Bang Exploring the 40-year history of “Saturday Night (In Stereo) Å News Premiere) Miley Cyrus hosts and sons sons News Å KDLT % 5 % News (N) (N) Å Theory Live.” (In Stereo) (N) Å performs. -

1930 Brown and Gold 12 No 11 March 15, 1930

Regis University ePublications at Regis University Brown and Gold Archives and Special Collections 3-15-1930 1930 Brown and Gold 12 No 11 March 15, 1930 Follow this and additional works at: https://epublications.regis.edu/brownandgold Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, and the Education Commons Recommended Citation "1930 Brown and Gold 12 No 11 March 15, 1930" (1930). Brown and Gold. 71. https://epublications.regis.edu/brownandgold/71 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Archives and Special Collections at ePublications at Regis University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Brown and Gold by an authorized administrator of ePublications at Regis University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ~1111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111! ~~~IIIIIIIIIUIIIIUIIIUIIIIIII111111fdiiiiiii111111111111111111111UIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIlll~ St. Patrick's St. Patrick's Day Day Edition GOI!D Edition finllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllltlllltlllllllltlllllllllllllllltllllll~ fl'l!lllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll!llllllllllllll:lllllllllllllllll/11111111111111111111111111111111~ Vol. XII, No. 11. REGIS COLLEGE, DENVER, COLO. March 15, 1930. 1 Catholic Literature NEW -HEATING PLANT I 'Twas only an Irishman's Dream· IRISH SAINT BORN Club Formed INSTALLED 'IN HALL IN SCOTLAND 387 A~D. · I . ~ 'I ' Mr. Madgett, -:s.-J . has formed Daily we see machines taking th~ among the Freshmen an organization place of men; daily we see ·science 1 Many Miracles Accredited known as the Catholic Literature evolving devices that can do al:\y type II to Missionary Work Club. Its purpose is to create a taste of labor efficiently .,and quickly. ·of Saint Patrick for Catholic authors and to increase Mankind is in the . spifit (Of invention the reading of better literature and the world is in 'an -age .of prog By Jack Cummings among College students. -

Back at 'Last'

FINAL-1 Sat, Feb 27, 2016 5:00:34 PM Your Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment for the week of March 5 - 11, 2016 Some of the cast of “The Last Man on Earth” Back at HMA.HMA. .Car .Care . Systems . ‘Last’ WASH WINTER AWAY HMA Car Care AT1 x 5 HMA. 978.744.4444 Superb polishing, interiors, great body work and more. 24/7 Car Wash HMACARCARE.COM 72 North St. (Rte. 114), Salem, MA Newspaper Advertising Works! Massachusetts’ First Credit Union THIS Located at 370 HighlandSt. Avenue, Jean's Salem Credit Union AD SPOTET Filler 3 x 3 COULD1 BE x YOURS. 3 Serving over 15,000 Members • A Part of your Community since 1910 Ask us about very economical advertising in Saturday’s Salem News TV Spotlight Supporting over 60 Non-Profit Organizations & Programs (with an option to print a deeply ) discounted ad in The Salem News Serving the Employees of over 40 Businesses Contact: Glenda Duchesneau 978.219.1000 • www.stjeanscu.com 978-338-2540 • [email protected] Offices also located in Lynn, Newburyport & Revere Federally Insured by NCUA FINAL-1 Sat, Feb 27, 2016 5:00:36 PM 2 • Salem News • March 5 - 11, 2016 Where there’s a Will Video Will Forte’s post-apocalyptic comedy returns from hiatus releases By Jacqueline Spendlove scouring the continent for other sur- nale to seven — plus Phil’s es- With the emergence of new char- companion worms die off one by TV Media vivors of a virus that has wiped out tranged astronaut brother, Mike (Ja- acters being more of a season 1 fo- one, but just as he’s about to com- most of humanity, and just after giv- son Sudeikis, “We’re the Millers,” cus, the first half of the current sea- mit suicide by jettisoning himself hristmas break and then ing up, he meets the good-hearted 2013), who’s stranded out in space, son has followed the group as it into space, he spots a newborn some! It’s been almost three (albeit profoundly irritating) Carol unbeknownst to anyone.