Social Media Usage Patterns Among Ghanaian Digital Natives and Digital Immigrants: a Study Into Intergenerational Communication

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Thesis Presented to the School of Arts and Communication, Malmö University; in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Award of Master of Arts (M.A.) Degree

1 UNIVERSITY OF MALMÖ SWEDEN FACULTY OF CULTURE AND SOCIETY (SCHOOL OF ARTS AND COMMUNICATION) M.A. THESIS HOW CAN ICTs AND NEW/SOCIAL MEDIA REMEDY THE PROBLEM OF VITAL STATISTICS DEFICIENCIES IN GHANA? (THE CASE OF GHANA BIRTHS AND DEATHS REGISTRY DEPARTMENT): A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE SCHOOL OF ARTS AND COMMUNICATION, MALMÖ UNIVERSITY; IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF MASTER OF ARTS (M.A.) DEGREE. BY STEPHEN BAIDOO SUPERVISED BY: Ms. Helen Hambly Odame(PhD). Associate professor, University of Guelph, Canada. JUNE, 2012 2 CONTENT TABLE OF CONTENT…………………………………………………………………………………………….. 2 DECLARATION……………………………………………………………………………………………………….5 DEDICATION………………………………………………………………………………………………………….5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ............................................................................................6 PREFACE………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..7 CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION 1.0. GENERAL INTRODUCTION…………………………………….……………………………………9 1.1. PREVIOUS STUDY………………………………………………………………………………………..9 1.2. CURRENT STUDY…………………………………………………..………………………………..….11 1.3. THE GOAL OF THIS STUDY………………………………………………………..…………………12 1.4. RESEARCH OBJECTIVES…………………………………………………….…………………………12 1.5. RESEARCH QUESTIONS/HYPOTHESES…………………………………..……………………..13 1.6. IMPORTANCE OF THIS STUDY……………………………………………………………………….13 1.7. PROJECT RELEVANCE TO COMDEV…………………………………………..………………….14 1.8. FIELD PROBLEMS ENCOUNTERED………………………………………………….…………..,.14 CHAPTER 2. THEORY AND CONCEPT 2.0. INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………………..………………………15 2.1.0. THEORITICAL FRAMEWORK……………………………………………………………………………15 -

Digital Access: the Future of Financial Inclusion in Africa Acronyms

DIGITAL ACCESS: THE FUTURE OF FINANCIAL INCLUSION IN AFRICA ACRONYMS ADC Alternative Delivery Channel ISO International Organization for Standardization AFSD African Financial Sector Database IT Information Technology ARPU Average Revenue Per User KES Kenyan Shilling API Application Programming Interface KPI Key Performance Indicator ATM Automated Teller Machine KYC Know Your Customer B2P Business to Person LAPO MfB Lift Above Poverty Organization BCEAO Central Bank of West Africa (Banque Centrale Microfinance Bank des Etats de l’Afrique de l’Ouest) M-banking Mobile Banking BOI Banking Operations Intermediary M-wallet Mobile Wallet BVN Bank Verification Number MFI Microfinance Institution CEO Chief Executive Officer MM Mobile Money CBA Commercial Bank of Africa MSME Micro, Small and Medium Enterprise CBN Central Bank of Nigeria MTN Mobile Telephone Network CFA West African Franc, or Central African Franc MNO Mobile Network Operator CGAP Consultative Group to Assist the Poor MVNO Mobile Virtual Network Operator CRM Customer Relationship Management NFC Near Field Communication DFS Digital Financial Services OTC Over the Counter DJ Disc Jockey P2B Person to Business DVD Digital Versatile Disc P2P Person to Person E-banking Electronic Banking PC Personal Computer EFT Electronic Funds Transfer PIN Personal Identification Number EMI e-Money Issuer POS Point of Sale E-money Electronic Money PSP Payment Service Provider E-wallet Electronic Wallet E-warehousing Electronic Warehousing QR Quick Response FCMB First City Monument Bank RCT Randomized -

What Accounted for the Collapse of Unibank?

University of Ghana http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh UNIVERSITY OF GHANA BANK FAILURE IN GHANA: WHAT ACCOUNTED FOR THE COLLAPSE OF UNIBANK? BY ELIJAH BENSON (ID NUMBER: 10636240) A PROJECT WORK SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF FINANCE, UNIVERSITY OF GHANA BUSINESS SCHOOL, UNIVERSITY OF GHANA, LEGON, IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE AWARD OF A MASTER OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION, FINANCE. MAY, 2019 i University of Ghana http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh DECLARATION I, Elijah Benson, hereby declare that this research work is my original work and has not been presented in this University or any other university for any academic award. All references used in the work have been duly acknowledged. I bear sole responsibility for any shortcomings in this work. …………………………………………… ………………………………………………… ELIJAH BENSON DATE (10636240) ii University of Ghana http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh CERTIFICATION I hereby certify that this thesis was supervised in accordance with procedures laid down by the University. …………………………………………… ……………………………………………… DR. ELIKPLIMI KOMLA AGBLOYOR DATE (SUPERVISOR) iii University of Ghana http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh DEDICATION This study is dedicated to God Almighty for the strength and grace to see me through the entire research. I also dedicate this work to my wife, Mrs. Ruth Nana Ama Benson, for her love and unending support throughout the entire course. iv University of Ghana http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh ACKNOWLEDGEMENT My gratitude, first and foremost, goes to God Almighty for providing me with strength, good health and knowledge throughout this project. I also wish to acknowledge my supervisor, Dr. Elikplimi Komla Agbloyor, for his support and guidance throughout my research work. -

2018-Calbank-Annual-Report

CalBank Content Page Four-Year Group Consolidated Financial Summary 2 Board of Directors, Officials and Registered Office 3 Profile of Board of Directors 4 Chairman’s Report 7 Managing Director’s Report 10 Report of the Directors 15 Corporate Governance Statement 17 Report of the Auditors 22 Statements of Comprehensive Income 26 Statements of Financial Position 27 Statements of Changes in Equity 28 Statements of Cash Flows 30 Notes to the Financial Statements 31 1 CalBank FOUR-YEAR GROUP CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL SUMMARY 2018 2017 2016 2015 in thousands of Ghana Cedis Interest Income 773,270 668,128 557,631 466,822 Interest Expense (351,641) (317,096) (306,317) (218,192) Net Interest Income 421,629 351,032 251,314 248,630 Commissions and fees 69,543 68,063 67,133 65,330 Other Operating Income 28,085 43,137 48,730 87,056 Operating Income 519,257 462,232 367,177 401,016 Operating Expenses (229,616) (188,422) (150,883) (144,031) Net Impairment Loss on Financial Assets (66,735) (54,947) (199,243) (35,677) Profit Before Income Tax 222,906 218,863 17,051 221,308 Income Tax Expense (69,690) (65,965) (6,843) (55,070) Profit after Taxation 153,216 152,898 10,208 166,238 Total assets 5,419,299 4,223,138 3,618,858 3,364,500 Total Deposits 3,150,053 2,497,623 2,375,194 1,602,832 Loans and Advances 2,422,952 1,853,674 1,966,394 1,805,285 Total Shareholders’ Equity 779,445 672,070 519,503 519,499 Earnings per share (Ghana Cedis per share) 0.2449 0.2793 0.0187 0.3032 Dividends per share (Ghana Cedis per share 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000 0.0970 Number of Shares (‘000) 626,585 548,262 548,262 548,262 Return on Assets 2.8% 3.6% 0.3% 4.9% Return on Equity 19.7% 22.8% 2.0% 32.0% Capital Adequacy Ratio 22.0% 21.9% 19.3% 21.4% Cost-to-Income Ratio 44.2% 40.8% 41.1% 35.9% 2 CalBank CALBANK LIMITED BOARD OF DIRECTORS, OFFICIALS AND REGISTERED OFFICE BOARD OF DIRECTORS Paarock Asuman VanPercy (Chairman) Frank Brako Adu Jnr. -

2016 Ghana Social Media Rankings Report

2017 The 2016 Annual Ghana Social Media Report A RANKINGS REPORT ON THE MOST INFLUENTIAL BRANDS AND PERSONALITIES ON SOCIAL MEDIA IN GHANA A RESEARCH PROJECT BY CLIQAFRICA LIMITED AND AVANCE MEDIA WWW.CLIQAFRICA.COM/GSMR GSMR 2016 CLIQAFRICA |AVANCE MEDIA FOREWORD With the growing dynamism in the global digital space, digital trends in 2016 show an increased sophistication of our social world and increased connectivity of human online activities specifically on social media. The year 2016 also witnessed several online controversies and events both globally and locally such as the #Brexit trend to various elections conversations, notable among them were the 2016 US Election, the 2016 Ghana elections and the Gambian Elections which occurrences happened almost concurrently and sparked an unending social revolution and brand advocacy. Social Media shaped how these controversies spurred generally with more online or digital platforms as well as brands focusing on media sharing on social media communities for traffic generation rather than employing any other network to reach out to audience. We also saw a global changing trend in content delivery and consumption as well as changing behavioral patterns of users and audience on these social networks. Social media measurement and monitoring thus became one of the most important features for most brands, organizations and businesses in their urge to guide their implementation of social campaigns and shape their online brand voice. In Ghana, various forecast and predictions were made notably by brands, personalities, organizations and civil society groups which spiraled these controversies to the extent of a proposed censorship of social media during the 2016 general elections as seen in other countries during periods of escalated controversies. -

“Internet Banking: an Initial Look at Ghanaian Bank Consumer Perceptions”

“Internet banking: an initial look at Ghanaian Bank Consumer Perceptions” Atsede Woldie AUTHORS Robert Hinson Habib Iddrisu Richard Boateng Atsede Woldie, Robert Hinson, Habib Iddrisu and Richard Boateng (2008). ARTICLE INFO Internet banking: an initial look at Ghanaian Bank Consumer Perceptions. Banks and Bank Systems, 3(3) RELEASED ON Thursday, 27 November 2008 JOURNAL "Banks and Bank Systems" FOUNDER LLC “Consulting Publishing Company “Business Perspectives” NUMBER OF REFERENCES NUMBER OF FIGURES NUMBER OF TABLES 0 0 0 © The author(s) 2021. This publication is an open access article. businessperspectives.org Banks and Bank Systems, Volume 3, Issue 3, 2008 Atsede Woldie (United Kingdom), Robert Hinson (Ghana), Habib Iddrisu (United Kingdom), Richard Boateng (United Kingdom) Internet banking: an initial look at Ghanaian bank consumer perceptions Abstract Internet banking is a tool in the service delivery arsenal for banks. This study focuses on client-bank relationship and on how Internet adoption may improve the qualitative relationship between banks and firms in Ghana and the business they serve. The study adopted a triangulation approach in meeting its objectives. A sample of 180 companies was sampled from the manufacturing, commerce, and services sectors of the economy. The findings of the study were mainly reported by means of descriptive statistics. The research findings indicate that Internet banking services are at their infant stage. Of the respondents, 68% had heard about Internet banking while 33% have never heard about it. 55% of the respondents said security concerns were the major barrier to the adoption of Internet banking. 55.6% of the firms that responded were not connected to the Internet whiles 44.4% were. -

Ghana-Banking-Survey-2019.Pdf

Banking reforms so far: topmost issues on the minds of bank CEOs August 2019 www.pwc.com/gh Table of contents CSP’s message 2 GAB CEO’s message 4 Tax Leader’s message 5 1 Economy of Ghana 7 2 Survey analysis 12 3 Banking industry overview 35 4 Total operating assets 39 5 Market share analysis 44 6 Profitability and efficiency 56 7 Return to shareholders 64 8 Liquidity 69 9 Asset quality 79 Appendices 84 PwC 2019 Ghana Banking Survey 1 CSP’s message their banks thus far, as well as the those related to the new minimum challenges and opportunities that capital requirement: they foresee. Heritage Bank Limited (HBL) and Highlights of the Premium Bank Ghana Limited (PBG) had their licences revoked. banking sector The reasons provided by BoG for the revocation of their licences reforms were insolvency in the case of Perhaps, one of the most significant Premium bank and questionable components of the banking sector source of capital for Heritage reforms is the new minimum capital bank. directive issued on 11 September Bank of Baroda (BoB) “closed 2017. The directive required shop” and exited the market on universal banks operating in Ghana their own volition also for reasons Vish Ashiagbor to increase their minimum stated related to the new minimum capital to GHS400 million by the capital requirement. Country Senior Partner end of 2018. BoG approved three mergers Following the deadline for involving six banks, effectively Background to this compliance, the changes in the accounting for three more exits. year’s survey banking sector have largely gone in The approved mergers are: 1. -

Special Report on Unibank

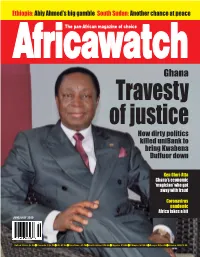

Ethiopia: Abiy Ahmed’s big gamble South Sudan: Another chance at peace AfricThe pan-Africana magazinew of achoice tch Ghana Travesty of justice How dirty politics killed uniBank to bring Kwabena Duffuor down Ken Ofori-Atta Ghana’s economic ‘magician’ who got away with fraud Coronavirus pandemic Africa takes a hit JUNE/JULY 2020 United States: $6.00 l Canada: C$6.50 l UK: £5.00 l Euro Zone: €5.50 l South Africa: R50.00 l Nigeria: N1000 l Ethiopia: Br100.0 l Kenya: KShs350 l Ghana: GH¢12.00 Special RepoRt Ghana TRAVESTY OF JUSTICE How dirty politics killed uniBank Special RepoRt uniBank The tragedy of uniBank ... and the targeting of Dr. Kwabena Duffuor A branch of uniBank Ghana which was closed down by the government on August 1, 2018. ot many people know about the dirty behind- Ministry of Finance regarding these actions. In that bombshell the-scenes politics that led to the collapse letter, Ofori Atta’s subordinates were instructed to keep its in August 2018 of one of Ghana’s largest contents “under wraps” – but it leaked nonetheless. indigenous banks, uniBank. A bank that had What is worse: The government could have saved uniBank if it been going strong for the previous 16 years, wanted, but clearly chose not to. uniBank’s troubles began only 7 months Without even using taxpayers’ resources, the government could after President Nana Akufo-Addo came to have stopped uniBank from going under by simply paying the bank power in 2017. Just a year later the bank about GH¢1.0bn that the government and its related entities was dead, killed through an orchestrated and combined action by already owed uniBank. -

The Perspective of the Ghanaian Bank Customer

Improving Consumer Confidence in Banking Post Bank Crisis: The Perspective of the Ghanaian Bank Customer by Albert Kamason A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Business Administration Dissertation Committee: Professor Charles Saunders, Ph.D., Dissertation Committee Chair Professor Eboni Hill, Ph.D., Committee Member Professor Andy Igonor, Ph.D., Committee Member Franklin University May 18, 2020 i Abstract The purpose of the study was to explore the effects of the Ghanaian banking crisis on the customers. The study identified and uncovered what the perspective of the affected customers were and what they thought the banks should focus on to help restore and improve the lost confidence in the Ghanaian banking industry. A general qualitative research design was selected because it was suitable for gaining an in-depth view of customers' experiences and their perspective of the Ghanaian banking landscape. Data was collected using open-ended semi- structured interview questions. Data collection gathered responses from 20 banking customers spread across Accra and Kumasi: ten from Accra and the remaining ten from Kumasi selected using convenience and snowball sampling methods from the population of the affected customers of some of the failed banks in Ghana. The data collected information on customers' banking experiences during the crisis, fluctuation of their confidence in the banking system and ideas on how they thought banking confidence could be restored and improved in Ghana. The study found that confidence had declined significantly during and after the bank crisis and the perspective of customers about the future of the Ghanaian banks is gloomy. -

The Intermedia Agenda-Setting Among Twitter, Instagram

University of Ghana http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh THE INTERMEDIA AGENDA-SETTING AMONG TWITTER, INSTAGRAM AND ONLINE NEWS WEBSITES IN GHANA BY EUGENE BROWN NYARKO AGYEI 10421222 THIS THESIS IS SUBMITTED TO THE UNIVERSITY OF GHANA, LEGON, IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE AWARD OF MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY IN COMMUNICATION STUDIES DEGREE JULY, 2019 University of Ghana http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh University of Ghana http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh DEDICATION To my amazing mother, Adwoa Sakyibea, who would break her back for me any day so I can do better, and to my father, Yaw Agyei. It is also dedicated to my supportive siblings - Biama, Asiedu and Nana, and to the memory of my beloved brother, Offei – I kept the promise. ii University of Ghana http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I give praises to God, for he has been good to me and his faithfulness endures forever. I am very grateful to him for giving me the strength to finish this work, that will partly, help me move to the next level of my life. Special thanks to my parents and siblings for their love, support and prayers throughout this tough, yet rewarding journey. I did this because you were there for me. A special appreciation to my amazing and supportive supervisor, Dr. Sarah Akrofi-Quarcoo, for her consistent supervision and input, and for treating me more of a son than a student. Her constant guidance, motivation and corrections made this work see the light of day. And to Professor Audrey Gadzekpo who has been more than supportive, I thank her for the mentorship and for always checking up on the progress of this work. -

University of California, Berkeley A0143 B0143

U.S. Department of Education Washington, D.C. 20202-5335 APPLICATION FOR GRANTS UNDER THE National Resource Centers and Foreign Language and Area Studies Fellowships CFDA # 84.015A PR/Award # P015A180143 Gramts.gov Tracking#: GRANT12660069 OMB No. , Expiration Date: Closing Date: Jun 25, 2018 PR/Award # P015A180143 **Table of Contents** Form Page 1. Application for Federal Assistance SF-424 e3 2. Standard Budget Sheet (ED 524) e6 3. Assurances Non-Construction Programs (SF 424B) e8 4. Disclosure Of Lobbying Activities (SF-LLL) e10 5. ED GEPA427 Form e11 Attachment - 1 (1234-UCB_GEPA427-June2018) e12 6. Grants.gov Lobbying Form e23 7. Dept of Education Supplemental Information for SF-424 e24 8. ED Abstract Narrative Form e25 Attachment - 1 (1237-2018UCBAfricaNRCFLAS.Abstract) e26 9. Project Narrative Form e27 Attachment - 1 (1235-3.UCB.CAS-TitleVINRC.2018.Narrative.FINAL) e28 10. Other Narrative Form e78 Attachment - 1 (1236-OtherAttachmnets_Final) e79 11. Budget Narrative Form e298 Attachment - 1 (1238-4.2018UCBAfricaNRCFLASBudgetNarrtvSprdSht) e299 Attachment - 2 (1239-DetailedBudget) e308 This application was generated using the PDF functionality. The PDF functionality automatically numbers the pages in this application. Some pages/sections of this application may contain 2 sets of page numbers, one set created by the applicant and the other set created by e-Application's PDF functionality. Page numbers created by the e-Application PDF functionality will be preceded by the letter e (for example, e1, e2, e3, etc.). Page e2 OMB Number: 4040-0004 Expiration Date: 12/31/2019 Application for Federal Assistance SF-424 * 1. Type of Submission: * 2. Type of Application: * If Revision, select appropriate letter(s): Preapplication New Application Continuation * Other (Specify): Changed/Corrected Application Revision * 3. -

The New Normal: Banks' Response to COVID-19

August 2020 The new normal: Banks’ response to COVID-19 www.pwc.com/gh 2 PwC | Ghana Banking Survey 2020 Table of contents CSP’s message 4 Message from GAB8 Tax Leader’s message 10 1 Economy of Ghana1 3 2 Survey Analysis 17 3 Banking Industry Overview 52 4 Total Operating Assets 56 5 Market Share Analysis 60 6 Profitability and Efficiency 70 7 Return on Shareholders' Funds 76 8 Liquidity 82 9 Asset Quality9 1 Appendices 95 3 PwC | Ghana Banking Survey 2020 CSP’s Message CSP’s Message Background There is no doubt that the COVID-19 pandemic has somewhat transformed the world’s way of life. Vish Ashiagbor Country Senior Partner In many ways, the world’s future – as previously In most cases, the world had not fully passed the envisaged or forecasted, which most analysts future-proof readiness test at first instance. In its expected to manifest in 2025, 2030, and in some recovery and seeking to return life to normalcy, cases 2050 – has become (or is fast becoming) the world has reduced physical contact among our present; what many are calling the “new humans and retreated into a virtual world. Now, normal”. more than ever in the world’s history, there is almost no process or service that can be The novel Coronavirus has impacted every facet completely executed without leveraging a digital of our lives; healthcare, education, trade and platform, and banking is no different. commerce, hospitality, banking and financial services, government services etc. An overview of the industry at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic In Ghana, at the early stages of the pandemic in March 2020, the government outlined measures to restrict movement and reduce non-essential physical contact between persons.