Interview with Brian Robison by Forrest Larson for the Music at MIT

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Land of Harmony a M E R I C a N C H O R a L G E M S

invites you to The Land of Harmony A MERIC A N C HOR A L G EMS April 5 • Shaker Heights April 6 • Cleveland QClevelanduire Ross W. Duffin, Artistic Director The Land of Harmony American Choral Gems from the Bay Psalm Book to Amy Beach April 5, 2014 April 6, 2014 Christ Episcopal Church Historic St. Peter Church shaker heights cleveland 1 Star-spangled banner (1814) John Stafford Smith (1750–1836) arr. R. Duffin 2 Psalm 98 [SOLOISTS: 2, 3, 5] Thomas Ravenscroft (ca.1590–ca.1635) from the Bay Psalm Book, 1640 3 Psalm 23 [1, 4] John Playford (1623–1686) from the Bay Psalm Book, 9th ed. 1698 4 The Lord descended [1, 7] (psalm 18:9-10) (1761) James Lyon (1735–1794) 5 When Jesus wep’t the falling tear (1770) William Billings (1746–1800) 6 The dying Christian’s last farewell (1794) [4] William Billings 7 I am the rose of Sharon (1778) William Billings Solomon 2:1-8,10-11 8 Down steers the bass (1786) Daniel Read (1757–1836) 9 Modern Music (1781) William Billings 10 O look to Golgotha (1843) Lowell Mason (1792–1872) 11 Amazing Grace (1847) [2, 5] arr. William Walker (1809–1875) intermission 12 Flow gently, sweet Afton (1857) J. E. Spilman (1812–1896) arr. J. S. Warren 13 Come where my love lies dreaming (1855) Stephen Foster (1826–1864) 14 Hymn of Peace (1869) O. W. Holmes (1809–1894)/ Matthias Keller (1813–1875) 15 Minuet (1903) Patty Stair (1868–1926) 16 Through the house give glimmering light (1897) Amy Beach (1867–1944) 17 So sweet is she (1916) Patty Stair 18 The Witch (1898) Edward MacDowell (1860–1908) writing as Edgar Thorn 19 Don’t be weary, traveler (1920) [6] R. -

Rediscovering Frédéric Chopin's "Trois Nouvelles Études" Qiao-Shuang Xian Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2002 Rediscovering Frédéric Chopin's "Trois Nouvelles Études" Qiao-Shuang Xian Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Xian, Qiao-Shuang, "Rediscovering Frédéric Chopin's "Trois Nouvelles Études"" (2002). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2432. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2432 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. REDISCOVERING FRÉDÉRIC CHOPIN’S TROIS NOUVELLES ÉTUDES A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Qiao-Shuang Xian B.M., Columbus State University, 1996 M.M., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2002 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF EXAMPLES ………………………………………………………………………. iii LIST OF FIGURES …………………………………………………………………………… v ABSTRACT …………………………………………………………………………………… vi CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………….. 1 The Rise of Piano Methods …………………………………………………………….. 1 The Méthode des Méthodes de piano of 1840 -

⁄Sþç}˛Ðn‚9Ô£ Rð˘¯Þ

559191 bk BEACH EU 25/05/2004 04:34pm Page 16 To her whose voice and loving hands fl Though I take the wings of morning, Op. 152 Can soothe our heart’s unrest, (1941) MERICAN LASSICS We bring these flowers, fragrant, fair, Though I take the wings of morning A C Our life her love hath blest! To the utmost sea, MAY FLOWERS Lyrics by Ana Mulford Addison Moody Yet my soul hath no sojourning Music by Amy Beach g1933 A.P. SCHMIDT CO. To outdistance Thee. Copyright Renewed and Assigned to SUMMY-BIRCHARD AMY BEACH MUSIC, a division of SUMMY-BIRCHARD INC. Though I climb to highest heaven, All Rights Reserved. Used by Permission of Warner Bros. ’Tis Thy dwelling high; Publications U.S. Inc. Though to death’s dark chamber given, Thou art standing by. fi I sought the Lord, Op. 142 (1937) Songs I sought the Lord, and afterward I knew If I say, the darkness hides me, He moved my soul to seek Him, seeking me; Turns my night to day; It was not I that found, O Saviour true; For with Thee no dark can find me, No, I was found of Thee. Shadows must away! The Year’s at the Spring Thou didst reach forth Thy hand and mine enfold; Even so, Thy hand shall lead me, I Sought the Lord I walked and sank not on the stormy sea; Flee Thee as I will; ’Twas not so much that I on Thee took hold, And Thy strong right arm shall hold me: As Thou, dear Lord, on me. -

Firebird, Winger & Watts

FIREBIRD, WINGER & WATTS A E G I S CLASSICAL SERIES S C I E N C E S FOUNDATION EST. 2013 THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 14, AT 7 PM | FRIDAY & SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 15 & 16, AT 8 PM NASHVILLE SYMPHONY GIANCARLO GUERRERO, conductor THANK YOU TO ANDRÉ WATTS, piano OUR PARTNER CLAUDE DEBUSSY Prélude à l’Après-midi d’un faune SERIES PRESENTING PARTNER [Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun] EDWARD MACDOWELL Concerto No. 2 in D minor for Piano and Orchestra, Op. 23 I. Larghetto calmato II. Presto giocoso III. Largo - Molto allegro INTERMISSION KIP WINGER Conversations with Nijinsky Chaconne de feu Waltz Solitaire Souvenir Noir L’Immortal IGOR STRAVINSKY Suite from The Firebird (1919 revision) I. Introduction and Dance of the Firebird II. Dance of the Princesses III. Infernal Dance of King Kastchei IV. Berceuse A E G I S V. Finale S C I E N C E S FOUNDATION EST. 2013 INCONCERT 21 TONIGHT’S CONCERT AT A GLANCE CLAUDE DEBUSSY Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun • Inspired by French writer Stéphane Mallarmé’s 1876 poem, Debussy’s Prelude to the Afternoon of the Faun is a single-movement piece in which Debussy evokes the source material through lush woodwind colors. The iconic flute theme gently sets the scene for an impressionistic musical tableau of a faun playing the panpipes in the woods. The metric ambiguity of the piece, along with sparing use of brass and percussion, adds to the distinctive feel. • The composer’s musical interpretation pleased Mallarmé, who praised the work, saying, “The music prolongs the emotion of the poem and fixes the scene more vividly than colors could have done.” EDWARD MACDOWELL Piano Concerto No. -

The Nineteenth Century, Part 2: Nationalism and Ideology

A-R Online Music Anthology www.armusicanthology.com Content Guide The Nineteenth Century, Part 2: Nationalism and Ideology Joseph E. Jones is Associate Professor at Texas A&M by Joseph E. Jones and Sarah Marie Lucas University-Kingsville. His research has focused on German opera, especially the collaborations of Strauss Texas A&M University-Kingsville and Hofmannsthal, and Viennese cultural history. He co- edited Richard Strauss in Context (Cambridge, 2020) Assigned Readings and directs a study abroad program in Austria. Core Survey Sarah Marie Lucas is Lecturer of Music History, Music Historical and Analytical Perspectives Theory, and Ear Training at Texas A&M University- Composer Biographies Kingsville. Her research interests include reception and Supplementary Readings performance history, as well as sketch studies, particularly relating to Béla Bartók and his Summary List collaborations with the conductor Fritz Reiner. Her work at the Budapest Bartók Archives was supported by a Genres to Understand Fulbright grant. Musical Terms to Understand Contextual Terms, Figures, and Events Main Concepts Scores and Recordings Exercises This document is for authorized use only. Unauthorized copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. If you have questions about using this guide, please contact us: http://www.armusicanthology.com/anthology/Contact.aspx Content Guide: The Nineteenth Century, Part 2 (Nationalism and Ideology) 1 ______________________________________________________________________________ Content Guide The Nineteenth Century, -

The Dallas Symphony Orchestra Presents: the Nature of Music May, 2021 Dear Fellow Educators

The Dallas Symphony Orchestra Presents: The Nature of Music May, 2021 Dear Fellow Educators, As spring arrives each year, I am reminded of the powerful relationship between nature and music. Both start as a single seed (or note!) and go on to blossom into something beautiful. Each plant, like each piece of music, is both a continuation of what came before and the start of something new. With Earth Day just a few weeks before our May concert, we wanted to use this Youth Concert as a way to explore and honor our planet through the lens of classical music. During our program, The Nature of Music, you and your students will hear music inspired by rivers, wildflowers, birds, and a busy bumblebee! Musicians have often used the earth’s natural beauty as inspiration for their music, and they try to use musical sounds to paint a picture for our ears, much like an artist would use different colors to paint a picture for our eyes. Each lesson will help your students explore and experience this connection. This concert will be offered virtually (available May 16 – June 4) but we are also accepting reservations for in-person viewing! Our two back-to-back concerts will be on Wednesday, May 5 at 10am and 11:30am. Please contact me or email my colleague in sales, Sabrina Siggers (contact information below), to reserve your classes reservation. You can see up-to-date Meyerson safety protocol below. We humans have a responsibility to respect and care for animals, plants, and the earth’s natural resources. -

Enrico Caruso

NI 7924/25 Also Available on Prima Voce ENRICO CARUSO Opera Volume 3 NI 7803 Caruso in Opera Volume One NI 7866 Caruso in Opera Volume Two NI 7834 Caruso in Ensemble NI 7900 Caruso – The Early Years : Recordings from 1902-1909 NI 7809 Caruso in Song Volume One NI 7884 Caruso in Song Volume Two NI 7926/7 Caruso in Song Volume Three 12 NI 7924/25 NI 7924/25 Enrico Caruso 1873 - 1921 • Opera Volume 3 and pitch alters (typically it rises) by as much as a semitone during the performance if played at a single speed. The total effect of adjusting for all these variables is revealing: it questions the accepted wisdom that Caruso’s voice at the time of his DISC ONE early recordings was very much lighter than subsequently. Certainly the older and 1 CAVALLERIA RUSTICANA, Mascagni - O Lola ch’ai di latti la cammisa 2.50 more artistically assured he became, the tone became even more massive, and Rec: 28 December 1910 Matrix: B-9745-1 Victor Cat: 87072 likewise the high A naturals and high B flats also became even more monumental in Francis J. Lapitino, harp their intensity. But it now appears, from this evidence, that the baritone timbre was 2 LA GIOCONDA, Ponchielli - Cielo e mar 2.57 always present. That it has been missed is simply the result of playing the early discs Rec: 14 March 1910 Matrix: C-8718-1 Victor Cat: 88246 at speeds that are consistently too fast. 3 CARMEN, Bizet - La fleur que tu m’avais jetée (sung in Italian) 3.53 Rec: 7 November 1909 Matrix: C-8349-1 Victor Cat: 88209 Of Caruso’s own opinion on singing and the effort required we know from a 4 STABAT MATER, Rossini - Cujus animam 4.47 published interview that he believed it should be every singers aim to ensure ‘that in Rec: 15 December 1913 Matrix: C-14200-1 Victor Cat: 88460 spite of the creation of a tone that possesses dramatic tension, any effort should be directed in 5 PETITE MESSE SOLENNELLE, Rossini - Crucifixus 3.18 making the actual sound seem effortless’. -

10-06-2018 Aida Mat.Indd

Synopsis Act I Egypt, during the reign of the pharaohs. At the royal palace in Memphis, the high priest Ramfis tells the warrior Radamès that Ethiopia is preparing another attack against Egypt. Radamès hopes to command the Egyptian army. He is in love with Aida, the Ethiopian slave of Princess Amneris, the king’s daughter, and he believes that victory in the war would enable him to free and marry her. But Amneris also loves Radamès and is jealous of Aida, whom she suspects of being her rival for Radamès’s affection. A messenger brings news that the Ethiopians are advancing. The king names Radamès to lead the army, and all prepare for war. Left alone, Aida is torn between her love for Radamès and loyalty to her native country, where her father, Amonasro, is king. In the temple of Vulcan, the priests consecrate Radamès to the service of the god Ptah. Ramfis orders Radamès to protect the homeland. Act II Ethiopia has been defeated, and in her chambers, Amneris waits for the triumphant return of Radamès. Alone with Aida, she pretends that Radamès has fallen in battle, then says that he is still alive. Aida’s reactions leave no doubt that she loves Radamès. Amneris is certain that she will defeat her rival. At the city gates, the king and Amneris observe the victory celebrations and praise Radamès’s triumph. Soldiers lead in the captured Ethiopians, among them Amonasro, who signals his daughter not to reveal his identity as king. Amonasro’s eloquent plea for mercy impresses Radamès, and the warrior asks that the order for the prisoners to be executed be overruled and that they be freed instead. -

Signerede Plader Og Etiketter Og Fotos Signed Records and Labels and Photos

Signerede plader og etiketter og fotos Signed records and labels and photos Soprano Blanche Arral (10/10-1864 – 3/3-1945) Born in Belgium as Clara Lardinois. Studied under Mathilde Marchesi in Paris. Debut in USA at Carnegie Hall in 1909. Joined the Met 1909-10. Soprano Frances Alda (31/5-1879 – 18/9-1953) Born Fanny Jane Davis in New Zealand. Studied with Mathilde Marchesi in Paris, where she had her debut in 1904. Married Guilio Gatti-Casazza – the director of The Met – in 1910. Soprano Geraldine Farrar – born February 28, 1882 – in Melrose, Massachusetts – died March 11, 1967 in Ridgefield, Connecticut Was also the star in more than 20 silent movies. Amercian mezzo-soprano Zélie de Lussan – 1861 – 1949 (the signature is bleached) American tenor Frederick Jagel – June, 10, 1897 Brooklyn NY – July 5, 1982, San Francisco, California At the Met from 1927 - 1950 Soprano Elisabeth Schwartzkopf – Met radio transmission on EJS 176 One of the greatest coloratura sopranos. Tenor Benjamino Gigli (20/3-1890 – 30/11-1957) One of the greatest of them all. First there was Caruso, then Gigli, then Björling and last Pavarotti. Another great tenor - Guiseppe di Stefano (24/7-1921 – 3/3-2008) The Italian tenor Guiseppe Di Stefano’s carreer lasted from the late 40’s to the early 70’s. Performed and recorded many times with Maria Callas. French Tenor Francisco (Augustin) Nuibo (1/5-1874 Marseille – Nice 4.1948) The Paris Opéra from 1900. One season at The Met in 1904/05. Tenor Leo Slezak (18/8-1873 – 1/6-1946) born in what became Czeckoslovakia. -

This Album Presents American Piano Music from the Later Part of the Nineteenth Century to the Beginning of the Twentieth

EDWARD MacDOWELL and Company New World Records 80206 This album presents American piano music from the later part of the nineteenth century to the beginning of the twentieth. Chronologically it ranges from John Knowles Paine’s Fuga Giocosa, published in 1884, to Henry F. Gilbert’s Mazurka, published in 1902. The majority are from the nineties, a time of great prosperity and self-satisfaction in a nation of philanthropists and “philanthropied,” as a writer characterized it in The New York Times. Though the styles are quite different, there are similarities among the composers themselves. All were pianists or organists or both, all went to Europe for musical training, and all dabbled in the classical forms. If their compatriots earlier in the nineteenth century wrote quantities of ballads, waltzes, galops, marches, polkas, and variations on popular songs (New World Records 80257-2, The Wind Demon), the present group was more likely to write songs (self-consciously referred to as “art songs”) and pieces with abstract titles like prelude, fugue, sonata, trio, quartet, and concerto. There are exceptions. MacDowell’s formal works include two piano concertos, four piano sonatas, and orchestra and piano suites, but he is perhaps best known for his shorter character pieces and nature sketches for piano, such as Fireside Tales and New England Idyls (both completed in 1902). Ethelbert Nevin was essentially a composer of songs and shorter piano pieces, most of them souvenirs of his travels, but he, too, worked in the forms that had become most prestigious in his generation. The central reason for the shift away from dance-inspired and entertainment pieces to formal compositions was that American wealth created a culture that created a musical establishment. -

Saturday, March 22, 1941 760 Wov __ .1100 Wq.X11 ..1550

WMCA _ 570INN-Ye _810 WI...TRW...MO WBAY .660 WABO ....BOOWEVIl 1300 RADIO TODAY WOR_ 710 WI EN' .1010 WhOM. ._1450 WJZ. SATURDAY, MARCH 22, 1941 760 WOV __ .1100 WQ.X11 ..1550 Young People's Concert: New York Philharmonic-SymphonyWABO, NEWS BROADCASTS 11:05 A. M.-12:15. Morning WOR WABOAVNY431 6:30-WEAF, WJZ, :SO-WMCA., WH14 Foreign Policy Association Luncheon: Hotel AstorWQXR, 1:45-8. WABC 8 :45-WNYC - 6 :45,WEAF 8 :55-WQXR, WJZ Metropolitan Opera: Verdi's "Aida," With Bruns. eastagna, Stella 6:55-WOE 9:00-WRAP, WABC1 Roman, Giovanni Martinelli, Ezio Plaza, and OthersWJZ, 2-5:30. 7 :05-WQXR 9:30-WOE 7 :15-WHN, WMCA 9 :45-WILN Baseball: Dodgers-Red Sox, at Clearwater, Fla.WOR, 2:55-5:25. :30-WEAF 10 :00-WMCA. 7 :45-WABC :00-WOE, WNTO, Library of Congress Concert: Budapest QuartetWABC, 3-3:55. 7 :55-WJZ. WQXR WABO Governor Lehman on Catholic Charities ProgramWABC, 5:15-5:30, 8 :00-WRAP, Afternoon Grand Coulee Dam: Ceremonies at Starting of Electric Generators:12 :00-WEN, WQXR 2:45-WOE Governor Langlie; Message From President RooseveltWEAF, 4:02-12 :15-WMCA. 3:343-WQXR 4:30. 12 :25-WJZ WMCA, WEVD :30-WOK 3:45-WNY04 Drama: "Defense for America"; Rear Admiral Taussig, and Others-12:45-WEAlr 3:55-WARO WEAF, 7-7:30. 1:45-WMCA, WEAF 4:00-WRAP :00-WNY0 WABO People's Forum:"Hitler's Spring Plans"; Ralph Ingersoll,Sonia. 2:15-WEI4 5 :50-WABO Tamara, and OthersWABC, 7-7:30. -

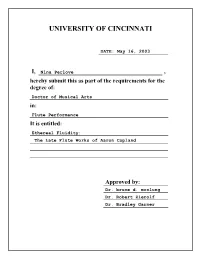

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI DATE: May 16, 2003 I, Nina Perlove , hereby submit this as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctor of Musical Arts in: Flute Performance It is entitled: Ethereal Fluidity: The Late Flute Works of Aaron Copland Approved by: Dr. bruce d. mcclung Dr. Robert Zierolf Dr. Bradley Garner ETHEREAL FLUIDITY: THE LATE FLUTE WORKS OF AARON COPLAND A thesis submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS (DMA) in the Division of Performance Studies of the College-Conservatory of Music 2003 by Nina Perlove B.M., University of Michigan, 1995 M.M., University of Cincinnati, 1999 Committee Chair: bruce d. mcclung, Ph.D. ABSTRACT Aaron Copland’s final compositions include two chamber works for flute, the Duo for Flute and Piano (1971) and Threnodies I and II (1971 and 1973), all written as memorial tributes. This study will examine the Duo and Threnodies as examples of the composer’s late style with special attention given to Copland’s tendency to adopt and reinterpret material from outside sources and his desire to be liberated from his own popular style of the 1940s. The Duo, written in memory of flutist William Kincaid, is a representative example of Copland’s 1940s popular style. The piece incorporates jazz, boogie-woogie, ragtime, hymnody, Hebraic chant, medieval music, Russian primitivism, war-like passages, pastoral depictions, folk elements, and Indian exoticisms. The piece also contains a direct borrowing from Copland’s film scores The North Star (1943) and Something Wild (1961).