UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Catanduanes Street

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exploring International Cuisine Reference Book

4-H MOTTO Learn to do by doing. 4-H PLEDGE I pledge My HEAD to clearer thinking, My HEART to greater loyalty, My HANDS to larger service, My HEALTH to better living, For my club, my community and my country. 4-H GRACE (Tune of Auld Lang Syne) We thank thee, Lord, for blessings great On this, our own fair land. Teach us to serve thee joyfully, With head, heart, health and hand. This project was developed through funds provided by the Canadian Agricultural Adaptation Program (CAAP). No portion of this manual may be reproduced without written permission from the Saskatchewan 4-H Council, phone 306-933-7727, email: [email protected]. Developed April 2013. Writer: Leanne Schinkel TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction .............................................................................................................................................................. 1 Objectives .............................................................................................................................................................. 1 Requirements ....................................................................................................................................................... 1 Tips for Success .................................................................................................................................................. 1 Achievement Requirements for this Project .......................................................................................... 2 Tips for Staying Safe ....................................................................................................................................... -

Fast Food Restaurants, Fast Casual Restaurants, and Casual Dining Restaurants

Commercial Revalue 2016 Assessment roll QUICK SERVICE RESTAURANTS AREA 413 King County, Department of Assessments Seattle, Washington John Wilson, Assessor Department of Assessments Accounting Division John Wilson 500 Fourth Avenue, ADM-AS-0740 Seattle, WA 98104-2384 Assessor (206) 205-0444 FAX (206) 296-0106 Email: [email protected] http://www.kingcounty.gov/assessor/ Dear Property Owners: Property assessments are being completed by our team throughout the year and valuation notices are being mailed out as neighborhoods are completed. We value your property at fee simple, reflecting property at its highest and best use and following the requirements of state law (RCW 84.40.030) to appraise property at true and fair value. We are continuing to work hard to implement your feedback and ensure we provide accurate and timely information to you. This has resulted in significant improvements to our website and online tools for your convenience. The following report summarizes the results of the assessments for this area along with a map located inside the report. It is meant to provide you with information about the process used and basis for property assessments in your area. Fairness, accuracy, and uniform assessments set the foundation for effective government. I am pleased to incorporate your input as we make continuous and ongoing improvements to best serve you. Our goal is to ensure every taxpayer is treated fairly and equitably. Our office is here to serve you. Please don’t hesitate to contact us if you should have questions, comments or concerns about the property assessment process and how it relates to your property. -

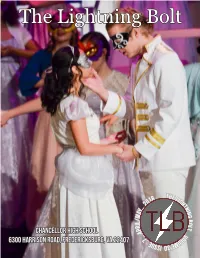

The Lightning Bolt

The Lightning Bolt 8 THE L 01 IGH . 2 T .. N y IN a G m B / O l i L T r p . A . V Chancellor High school . O . l 7 u . m e e u 6300 Harrison road, fredericksburg, va 22407 3 S S 0 I 1 April/May 2018 Mrs. Gattie Adviser Tyler Jacobs Editor-in-Chief Photo by Sarah Ransom and Naomi Nichols in the forefront, Jaime Ericson attends the Prince’s Ball in our spring makayla tardie dancing as townspeople. production of Cinderella Co-Editor-in-Chief/ Design editor Elizabeth Owusu News Editor becca Alicandro Photo by Makayla Tardie Photo by Lifetouch Ladies of the ball lament with one of Cinderella’s Kaitlyn Schwinn in action during a game. Features Editor stepsisters, played by Olivia Royster. Savannah Aversa Junior sports editor Ava purcell Junior op-ed editor Photo by TLB Staff Photo by TLB Staff The baseball team circles up in preparation before their game. Taylor sullivan Staff reporter Gynger adams staff reporter Photo by Makayla Tardie Photo by Molly McMullen Katelyn Siget and Molly McMullen chilling out at an Makayla Tardie, Natalie Masaitis, and Katelyn Siget art museum in D.C. taking a journey on the art field trip. April/May 2018 2 Editorials Going Beyond and Saying Goodbye By Tyler Jacobs indeed. longer be a Chancellor Charger, remain consistent and to always Editor-in-Chief While I am anxious to instead I’ll be transitioning to a have a smile for another person So here we are at the end of the pursue these paths, there is a Rowan Prof. -

Exploring International Cuisine | 1

4-H MOTTO Learn to do by doing. 4-H PLEDGE I pledge My HEAD to clearer thinking, My HEART to greater loyalty, My HANDS to larger service, My HEALTH to better living, For my club, my community and my country. 4-H GRACE (Tune of Auld Lang Syne) We thank thee, Lord, for blessings great On this, our own fair land. Teach us to serve thee joyfully, With head, heart, health and hand. This project was developed through funds provided by the Canadian Agricultural Adaptation Program (CAAP). No portion of this manual may be reproduced without written permission from the Saskatchewan 4-H Council, phone 306-933-7727, email: [email protected]. Developed April 2013. Writer: Leanne Schinkel TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction .............................................................................................................................................................. 1 Objectives .............................................................................................................................................................. 1 Requirements ....................................................................................................................................................... 1 Tips for Success .................................................................................................................................................. 1 Achievement Requirements for this Project .......................................................................................... 2 Tips for Staying Safe ....................................................................................................................................... -

Cooperative Supper Theme: “Medieval Food History”

Culinary Historians of Washington, D.C. April 2013 Volume XVII, Number 7 Cooperative Supper Theme: CALENDAR CHoW Meetings “Medieval Food History” April 14 Sunday, April 14 Cooperative Supper 4:00 to 6:00 p.m. (Note: time change (note time change) 4:00 to 6:00 p.m.) Alexandria House 400 Madison Street Plates, cups, bowls, eating Alexandria, VA 22314 utensils, and napkins will be provided. t the March CHoW meeting, members But please bring anything voted for “Medieval Food History” as the April supper theme. The Middle needed for serving your A Ages or Medieval period is a stretch of Euro- contribution, as well as pean history that lasted from the 5th until the a copy of your recipe, 15th centuries. It began with the collapse of the the name of its source, Western Roman Empire, and was followed by and any interesting the Renaissance and the Age of Discovery. The information related to the Middle Ages is the middle period of the tradi- recipe you have chosen. tional division of Western history into Classi- cal, Medieval, and Modern periods. The period May 5 is subdivided into the Early Middle Ages, the Program High Middle Ages, and the Late Middle Ages. Up to the start of the Middle Ages when Wil- Amy Riolo and PHOTO: John, Duke of Berry enjoying a grand liam the Conqueror and the Normans invaded Sheilah Kaufman meal. The Duke is sitting at the high table under a England the only real influence on the types “Turkish Cuisine and the luxurious baldaquin in front of the fireplace, tended to by several servants including a carver. -

Background the Philippines Is an Archipelago (Chain of Islands) Comprised of Over 7,100 Islands in the Western Pacific Ocean. Or

Beatriz Dykes, PhD, RD, LD, FADA Background The Philippines is an archipelago (chain of islands) comprised of over 7,100 islands in the western Pacific Ocean. Originally inhabited by indigenous tribes such as the Negroid Aetas and the pro-Malays. Beginning in 300 BC up to 1500 AD, massive waves of Malays (from Malaysia, Sumatra, Singapore, Brunei, Burma, and Thailand) immigrated to the islands. Arab, Hindu and Chinese trading also led to permanent settlements during by these different groups during this period. In 1521, Spain colonized the Philippines, naming it after King Phillip II and bringing Christianity with them. The Spanish colonization which lasted 350 years, imparted a sense of identification with Western culture that formed an enduring part of the Philippine consciousness, unmatched anywhere else in Asia. The prevalence of Spanish names to this day (common first names like Ana, Beatriz, Consuelo, Maria and last names as Gonzales, Reyes, and Santos) reflects this long-standing influence of the Spanish culture. The United States acquired the Philippines from Spain for 20 million dollars after winning the Spanish-American war through the Treaty of Paris in 1898, introducing public education for the first time. During this period, health care, sanitation, road building, and a growing economy led to a higher standard of living among Filipinos and the Philippines became the third largest English speaking country in the world. Above all, the US occupation provided a basis for a democratic form of government. World War II had the Filipinos fighting alongside the Americans against the Japanese. The Death March and Corregidor became symbolic of the Philippine alliance with the United States. -

Research Dynamics Sample Report

Table of Contents Page I. Background and Objectives...................................................................................... 1 II. Methodology............................................................................................................. 2 III. Summary of Findings................................................................................................ 3 IV. Conclusions............................................................................................................... 6 V. Detailed Findings A. Unaided Awareness Of Fast-Food Restaurants That Serve Fried Chicken................................................................................... 11 B. Usage Of Fast-Food Restaurants For Fried Chicken ......................................... 13 C. Change In Visitation To Restaurants.................................................................. 15 D. Reasons For Change In Visits To Restaurant A ................................................ 16 E. Restaurant A Customer Profile........................................................................... 28 F. Rating Of Primary Fast-Food Restaurant For Fried Chicken............................................................................................... 34 G. Overall Opinion Of Restaurant A....................................................................... 37 H. Sample Demographic Profile ............................................................................. 38 VI. Appendix Background and Objectives As it develops various marketing -

Shake Shack Inc. (SHAK) Is an American-Born Premium Fast- Company Data

THE FINAL PAGE OF THIS REPORT CONTAINS A DETAILED DISCLAIMER The content and opinions in this report are written by university students from the CityU Student Research & Investment Club, and thus are for reference only. Investors are fully responsible for their investment decisions. CityU Student Research & Investment Club is not responsible for any direct or indirect loss resulting from investments referenced to this report. The opinions in this report constitute the opinion of the CityU Student Research & Investment Club and do not constitute the opinion of the City University of Hong Kong nor any governing or student body or department under the University. Rating HOLD October 14th, 2019 Price (10/19/2019 USD) 88.49 Target price (USD) 77.85 Americas % down from Price on 10/19/2019 12.02% Equity Research Market cap. (USD, b) 03.30 Restaurants Enterprise Value (USD b) 03.24 Stock ratings are relative to the coverage universe in each analyst's or each team's respective sector. Target price is for SHAKE SHACK INCORPORATED (SHAK:NYSE) 12 months. Research Analysts: Our analysis on ‘Shake Shack’ (from hereupon referred to as “Shake Shack”, Murtaza Salman Abedin “Shack” or “SHAK”) is Discounted Cash Flow valuation-driven. Shake +852 59858568 [email protected] Shack is a growing brand with rapidly rising potential, however being a small company it still faces various growth-oriented challenges. Our Daria Yong-Tong Yip [email protected] Valuation gives SHAK a fair share value of USD 77.85 (HOLD) and this Samya Malhotra has been calculated through a DCF valuation of the 5-Year forecast period [email protected] ranging from 2019E to 2023E. -

Brunch & Drunch

BRUNCH & DRUNCH Disfruta del domingo Una forma fantástica de disfrutar del domingo es olvidarse del reloj y compartir un buen ágape con los amigos. El conocido brunch, originario de Estados Unidos, invade los restaurantes y hoteles más cool de nuestras ciudades. Pero hay mas...llega el drunch, apropiándose de la tarde dominical, con la misma filosofía del brunch. Te contamos más sobre éstas dos magníficas propuestas gastronómicas. EL BRUNCH....LOS ORÍGENES El brunch (nombre que proviene de la fusión de breakfast y lunch), nace a finales del siglo XIX en la ciudad de Nueva York, entre los miembros de la alta sociedad de la época, que tras las alocadas noches del sábado, necesitaban reponer fuerzas al día siguiente con un desayuno-comida rico en calorías. La tradición dice que el brunch debe consistir en: Café, Huevos Benedict (escalfados y servidos en tostadas con beicon y salsa holandesa) y un Bloody Mary. El Brunch se realiza por la mañana, entre el desayuno y el almuerzo. QUÉ SE TOMA EN UN BRUNCH.... Es una fusión entre los alimentos que se toman habitualmente para el desayuno y platos que solemos comer en la comida, como por ejemplo zumos, huevos, bollos...con ensaladas, ahumados, steak tartar, etc. El objetivo es conseguir una mezcla equilibrada entre ingredientes dulces y salados. Cada uno puede adaptar el brunch a su gusto y en los locales más de moda, como hoteles o restaurantes, ofrecen ésta opción gastronómica, incluyendo en ocasiones platos de alta cocina. El brunch cuenta con algunos (o todos) de los siguientes ingredientes: ZUMOS Y BEBIDAS: Zumos naturales, de frutas y/o verduras de la temporada, aguas, infusiones, cafés y refrescos. -

Breakfast Specials* $9.99 Served with Steamed Rice Or Garlic Fried Rice, Two Eggs, and Achara (Pickled Papaya)

R E S T A U R A N T FILIPINO MENU Breakfast Specials* $9.99 Served with steamed rice or garlic fried rice, two eggs, and achara (pickled papaya). Tapa Tapa Sweet and delicious. Cured and marinated beef sirloin slices. Longanisa Delicious Filipino style cured and marinated pork sausages. Longanisa Tocino Sweet and delicious cured and marinated pork tenderloin slices. Daing na Bangus A Filipino tradition. Deep fried boneless milk fish. Tocino Tinapang Bangus $10.99* A Filipino tradition. Smoked boneless milk fish. Picadillo Sautéed ground beef with potatoes, carrots, red peppers and green peas. Carne Norte Filipino style corned beef. Daing na Bangus Relyenong Talong FOR CARRY OUT, PLEASE CALL 703-532-0616 Filipino style eggplant pork omelet. * Items are served raw or undercooked or contain raw or undercooked ingredients. Consuming raw or undercooked meats, poultry or eggs may increase your Tortang Giniling na Karne risk of foodborne illnesses Filipino style ground pork omelet with green peas and red peppers. Relyenong Talong * Items are served raw or undercooked or contain raw or undercooked ingredients. Consuming raw or undercooked meats, poultry or eggs may increase your risk of foodborne illnesses R E S T A U R A N T FILIPINO MENU Lunch / Dinner Served with steamed rice or garlic fried rice. Chicken or Pork Adobo ........................... $ 9.99 Adobo Filipino National Dish, in a vinegar sauce. Binagoongan Baboy .................................. $ 9.99 Pork in shrimp paste. Fried Stuffed Shrimp Lumpia ................ $10.99 Shrimp eggroll. Lechon Kawali .............................................. $ 9.99 Lechon Kawali Deep fried pork belly pieces, served with special Mang Tomas sauce. -

Fast Food Restaurants, Fast Casual Restaurants, and Casual Dining Restaurants

Commercial Revalue 2017 Assessment roll QUICK SERVICE RESTAURANTS AREA 413 King County, Department of Assessments Seattle, Washington John Wilson, Assessor Department of Assessments 500 Fourth Avenue, ADM-AS-0708 John Wilson Seattle, WA 98104-2384 OFFICE: (206) 296-7300 FAX (206) 296-0595 Assessor Email: [email protected] http://www.kingcounty.gov/assessor/ Dear Property Owners, Our field appraisers work hard throughout the year to visit properties in neighborhoods across King County. As a result, new commercial and residential valuation notices are mailed as values are completed. We value your property at its “true and fair value” reflecting its highest and best use as prescribed by state law (RCW 84.40.030; WAC 458-07-030). We continue to work hard to implement your feedback and ensure we provide accurate and timely information to you. We have made significant improvements to our website and online tools to make interacting with us easier. The following report summarizes the results of the assessments for your area along with a map. Additionally, I have provided a brief tutorial of our property assessment process. It is meant to provide you with the background information about the process we use and our basis for the assessments in your area. Fairness, accuracy and transparency set the foundation for effective and accountable government. I am pleased to continue to incorporate your input as we make ongoing improvements to serve you. Our goal is to ensure every single taxpayer is treated fairly and equitably. Our office is here to serve you. Please don’t hesitate to contact us if you ever have any questions, comments or concerns about the property assessment process and how it relates to your property. -

Page MEDITERRANEAN 2013

Barcelona, Spain OVERVIEW Introduction Barcelona, Spain's second-largest city, is inextricably linked to the architecture of Antoni Gaudi. His most famous and unfinished masterpiece, La Sagrada Familia, is the emblem of the city. Like the basilica, Barcelona takes traditional ideas and presents them in new, even outrageous, forms. And the city's bursts of building and innovation give the impression that it's still being conceived. Both the church and the city can be tough places to get a handle on, yet their complexity is invigorating rather than forbidding. Since it hosted the Summer Olympics in 1992, Barcelona has been on the hot list of European destinations. The staging of the Universal Forum of Cultures in 2004 also raised the city's profile. Such popularity may make it harder to land a hotel room, but it has only added to the sense that Barcelona is a place to visit as much for its energetic, cosmopolitan character as for its unusual attractions. Must See or Do Sights—La Sagrada Familia; La Pedrera; La Catedral (La Seu); Santa Maria del Mar. Museums—Museu Picasso; Museu Nacional d'Art de Catalunya; Museu d'Historia de Catalunya; Fundacio Joan Miro. Memorable Meals—Lunch at Escriba Xiringuito on the seafront; high-end Mediterranean fare at Neichel; seafood at Botafumeiro; fashionable, inventive dishes at Semproniana. Late Night—Flamenco at Los Tarantos in summer; drinks and a view at Mirablau; wine at La Vinya del Senyor; dancing at Otto Zutz or Boulevard Culture Club. Walks—La Rambla, the Barri Gotic and the Born; along the waterfront; Montjuic; Park Guell; Collserola woodlands.