Danielle Tate Angels and Demons Final Paper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spike: the Devil You Know Free

FREE SPIKE: THE DEVIL YOU KNOW PDF Franco Urru,Chris Cross,Bill Williams | 104 pages | 04 Jan 2011 | Idea & Design Works | 9781600107641 | English | San Diego, United States Spike: The Devil You Know - Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Angel Wiki Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to Spike: The Devil You Know. Want Spike: The Devil You Know Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. Preview — Spike by Bill Williams. Chris Cross. While out and about drinking, naturally Spike gets in trouble over a girl of course and finds himself in the middle of a conspiracy that involves Hellmouths, blood factories, and demons. Just another day in Los Angeles, really. But when devil Eddie Hope gets involved, they might just kill each other before getting to the bad guys! Get A Copy. Paperbackpages. More Details Other Editions 3. Friend Reviews. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. To ask other readers questions about Spikeplease sign up. Lists with This Book. Community Reviews. Showing Average rating 3. Rating details. More filters. Sort order. The mini series sees a new character Eddie Hope stumble into Buffyverse alumni, Spike! I enjoyed their conversations but the general story was sort of Then again, that is the Buffyverse way of handling things! Jan 30, Sesana rated it it was ok Shelves: comicsfantasy. Well, that was pointless. The story is dull enough that I doubt the writer was interested in it. -

Slayage, Number 3: Clark and Miller

Daniel A. Clark & P. Andrew Miller Buffy, the Scooby Gang, and Monstrous Authority: BtVS and the Subversion of Authority (1) Buffy the Vampire Slayer, like much of the fare on the WB network (the show's home for the first five seasons), is marketed to and most popular among younger viewers. Like Dawson's Creek, Charmed, Roswell, and Popular, it depicts a young attractive cast struggling with the issues that typically face young adult characters on television, if not young adults in real life. A recent promotional spot on the WB for these shows features the stars laughing, dancing, and partying. The spot ends with the phrase “The night is young” on the screen. Current promotional spots feature the same imagery with a hip-hop version of The Who's "My Generation" on the soundtrack. They are young and hip and appeal to a young audience that uses television as one of the cultural texts that informs their interpretive communities. There are a number of elements of BtVS that have potential significance for an audience, but the ones on which we choose to focus are the issues of authority and power in the show. Issues of power and authority provide the show with most of its plot lines as well as thematic context. (2) Authority is viewed primarily through the eyes of the show's teen protagonists and so takes on the guise of traditional figures from the spheres in which the characters travel: school authority embodied by administrators, teachers, professors, and coaches; social authority embodied by parents; and civic authority embodied by local and federal officials and police. -

Buffy at Play: Tricksters, Deconstruction, and Chaos

BUFFY AT PLAY: TRICKSTERS, DECONSTRUCTION, AND CHAOS AT WORK IN THE WHEDONVERSE by Brita Marie Graham A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English MONTANA STATE UNIVERSTIY Bozeman, Montana April 2007 © COPYRIGHT by Brita Marie Graham 2007 All Rights Reserved ii APPROVAL Of a thesis submitted by Brita Marie Graham This thesis has been read by each member of the thesis committee and has been found to be satisfactory regarding content, English usage, format, citations, bibliographic style, and consistency, and is ready for submission to the Division of Graduate Education. Dr. Linda Karell, Committee Chair Approved for the Department of English Dr. Linda Karell, Department Head Approved for the Division of Graduate Education Dr. Carl A. Fox, Vice Provost iii STATEMENT OF PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master’s degree at Montana State University, I agree that the Library shall make it availably to borrowers under rules of the Library. If I have indicated my intention to copyright this thesis by including a copyright notice page, copying is allowable only for scholarly purposes, consistent with “fair use” as prescribed in the U.S. Copyright Law. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this thesis in whole or in parts may be granted only by the copyright holder. Brita Marie Graham April 2007 iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS In gratitude, I wish to acknowledge all of the exceptional faculty members of Montana State University’s English Department, who encouraged me along the way and promoted my desire to pursue a graduate degree. -

Buffy the Vampire Slayer: Long Way Home Season 8, Volume 1 Free

FREE BUFFY THE VAMPIRE SLAYER: LONG WAY HOME SEASON 8, VOLUME 1 PDF Joss Whedon,Georges Jeanty,Andy Owens,Jo Chen | 136 pages | 16 Jan 2008 | Dark Horse Comics,U.S. | 9781593078225 | English | Milwaukie, United States The Long Way Home - Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Angel Wiki It is written by creator Joss Whedon. The first issue was released on March 14,[2] and the final issue of the arc was released on June 6, Buffy is leading a squad of Slayers —including three named LeahRowenaand Satsu —in a raid on a large, dilapidated church protected by a forcefield. She reveals that there are at least Slayers now active, of whom are working with the Scooby Gang spread over ten squads. There are two Slayers posing as decoys of her, lest she become an easy target; one literally underground and another in Rome publicly partying and dating the Immortal. Working with Xanderwho is running things at Slayer headquarters in Scotland Buffy refers to him as a Volume 1 despite his objections with a team of computer workers, psychics and mystics, including a Slayer named Renee, Buffy Volume 1 her squad find three monstrous demons. There are also three dead humans. The demons are killed in battle. The humans have odd symbols carved in their chest and there are nearby automatic weapons. Buffy tells Xander to send a copy of the symbol to Giles Buffy the Vampire Slayer: Long Way Home Season 8, when another Slayer finds the machine that generated the force field, also presumably belonging to the victims. There is a shadowed spy nearby. -

Opposing Buffy

Opposing Buffy: Power, Responsibility and the Narrative Function of the Big Bad in Buffy Vampire Slayer By Joseph Lipsett B.A Film Studies, Carleton University A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts in Film Studies Carleton University, Ottawa, Ontario April 25, 2006 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Library and Bibliotheque et Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-16430-3 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-16430-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce,Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve,sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet,distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform,et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Slayer and Signal: Joss Whedon Versus the Big Bads." Nerd Ecology: Defending the Earth with Unpopular Culture

Lioi, Anthony. "Slayer and Signal: Joss Whedon Versus the Big Bads." Nerd Ecology: Defending the Earth with Unpopular Culture. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016. 145–168. Environmental Cultures. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 2 Oct. 2021. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781474219730.ch-006>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 2 October 2021, 01:18 UTC. Copyright © Anthony Lioi 2016. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 5 Slayer and Signal: Joss Whedon Versus the Big Bads In which I argue that Buffy the Vampire Slayer confronts the problem of world-destruction in a California haunted by demons that suburbia refuses to acknowledge. It is a work of advanced nerdism whereby freaks and geeks become aware of their capacity for self-and-world-defense. Here, nerd culture considers what new tropes, plots, and characters are necessary to resist the Powers of predation and eugenics. Buffy figures these forces as demonic Powers in the Pauline sense: the spirits of broken social institutions that attempt to destroy the nerd. Chief among these demons is Gender, the system of norms that dictates what good boys and girls must do to please the Powers. The story of the Slayer begins with a solitary female messiah doomed to destroy vampires and be destroyed in turn; it evolves into a narrative of alliance in which rejected children defend the world by moving into the queer, the uncanny, and the monstrous. Buffy’s creator, Joss Whedon, extended his exploration of the effluvial and the degenerate through his space Western, Firefly/ Serenity, in which a band of misfits uncovers a government conspiracy to hide the poisoning of a planet, Miranda. -

All About Angels Dr

V VERITAS All About Angels Dr. Andrew Sulavik The Veritas Series is dedicated to Blessed Michael McGivney (1852-1890), priest of Jesus Christ and founder of the Knights of Columbus. The Knights of Columbus presents The Veritas Series “Proclaiming the Faith in the Third Millennium” All About Angels BY DR. ANDREW SULAVIK General Editor Reverend Gabriel B. O’Donnell, O.P. Catholic Information Service Knights of Columbus Supreme Council Imprimatur Daniel A. Cronin, S.T.D. Archbishop of Hartford November 8, 1999 Copyright © 1999-2021 by Knights of Columbus Supreme Council. All rights reserved. Citations from the Catechism of the Catholic Church are taken from the Catechism of the Catholic Church for the United States of America, copyright © 1994 by the United States Catholic Conference, Inc., Libreria Editrice Vaticana. All rights reserved. Cover: The Archangel Michael (14th c.). Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow, Russia. © Scala/Art Resource, New York. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Write: Catholic Information Service Knights of Columbus Supreme Council PO Box 1971 New Haven, CT 06521-1971 www.kofc.org/cis [email protected] 203-752-4267 800-735-4605 fax Printed in the United States of America CONTENTS What Catholics Believe About Angels ...................................... 5 The Visible.............................................................................. 5 The Invisible ........................................................................... 6 Creation, Angels and Christ..................................................... 6 Angels in the Bible.................................................................. 8 The Old Testament.................................................................. 9 The New Testament .............................................................. 11 The Church’s Doctrinal Statements on Angels...................... -

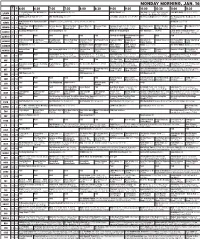

Monday Morning, Jan. 16

MONDAY MORNING, JAN. 16 FRO 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 COM 4:30 KATU News This Morning (N) Good Morning America (N) (cc) AM Northwest (cc) The View TV host Piers Morgan; Live! With Kelly (N) (cc) (TVPG) 2/KATU 2 2 (cc) (Cont’d) TV host Tim Gunn. (N) (TV14) KOIN Local 6 at 6am (N) (cc) CBS This Morning (N) (cc) Let’s Make a Deal (N) (cc) (TVPG) The Price Is Right (N) (cc) (TVG) The Young and the Restless (N) (cc) 6/KOIN 6 6 (TV14) NewsChannel 8 at Sunrise at 6:00 Today Giada De Laurentiis; James Morrison. (N) (cc) Anderson (cc) (TVG) 8/KGW 8 8 AM (N) (cc) Power Yoga: Mind Wild Kratts (cc) Curious George Cat in the Hat Super Why! (N) Dinosaur Train Sesame Street Jack Be Nimble Sid the Science Clifford the Big Martha Speaks WordWorld (TVY) 10/KOPB 10 10 and Body (TVY) (TVY) Knows a Lot (cc) (TVY) (TVY) attempts a big jump. (TVY) Kid (TVY) Red Dog (TVY) (TVY) Good Day Oregon-6 (N) Good Day Oregon (N) MORE Good Day Oregon The 700 Club (cc) (TVPG) Law & Order: Criminal Intent A car 12/KPTV 12 12 bomb kills three boys. (TV14) Paid Paid Paid Paid Paid Paid Through the Bible International Fel- Paid Paid Paid 22/KPXG 5 5 lowship Creflo Dollar Min- John Hagee Breakthrough This Is Your Day Believer’s Voice Northwest Focus Prophetic Whis- Always Good Education: A Jewish Voice (cc) Life Today With Today: Marilyn & 24/KNMT 20 20 istries (cc) Today (cc) (TVG) W/Rod Parsley (cc) (TVG) of Victory (cc) per (cc) News (cc) Higher Calling James Robison Sarah Eye Opener (N) (cc) My Name Is Earl My Name Is Earl Swift Justice: Swift Justice: Maury (cc) (TV14) The Steve Wilkos Show (cc) (TVPG) 32/KRCW 3 3 (TV14) (TV14) Jackie Glass Jackie Glass Andrew Wom- Paid The Jeremy Kyle Show (cc) (TVPG) America Now (cc) Divorce Court (N) Excused (N) (cc) Excused (cc) Cheaters (cc) Cheaters (N) (cc) America’s Court Judge Alex (N) 49/KPDX 13 13 mack (TVG) (TVPG) (TVPG) (TVPG) (TV14) (TV14) (cc) (TVPG) Paid Paid Intervention Rocky. -

In Revelation 11,18 – Who Are They?

The “Destroyers of the Earth” in Revelation 11,18 – Who are they? Eliezer González Abstract Revelation 11,18 is a verse that is commonly cited specifically in connection with caring for the earth and its natural resources. This paper will argue that in its appropriate context, the destruction of the earth to which Rev 11,18 refers is not the degradation of the natural environment of the earth. Rather, it refers to the outpouring of the seven plagues, for which ultimate responsibility, although it is God’s action, is attributed to the nations under the leadership of the beast. It is therefore exegetically inappropriate to use Rev 11,18 as a de-contextualized proof- text to urge environmental responsibility. Key Words Revelation – Two Witnesses – Ecology – Environment – Plagues – Destruction – Exegesis Resumen Apocalipsis 11,18 es un texto que se cita comúnmente en relación con el cuidado de la tierra y sus recursos naturales. Este artículo mostrará que, en su contexto apropiado, la destrucción de la tierra a la que se refiere Ap 11,18 no es la degradación del medio ambiente natural de la Tierra. Más bien, se refiere al derramamiento de las siete plagas, cuya responsabilidad última, aunque es una acción de Dios, se atribuye a la nación que está bajo el liderazgo de la bestia. Por lo tanto, es inadecuado exegéticamente usar Ap 11:18 como un texto prueba descontextualizado para instar a ser responsables con el medio ambiente. Palabras clave Apocalipsis – Dos testigos – Ecología – Medio ambiente – Plagas – Destrucción – Exégesis Introduction Revelation 11,18 is a verse that has been popularly used in some interesting contexts that were probably not in mind when the words were written. -

JOURNAL of BIBLICAL LITERATURE Ing the Hint There Given

156 JOURNAL Oll' BIBLICAL LITERATURE The Origin of the Names of Angels and Demons in the Extra-Canonical Apocalyptic Literature to 100 A.D. BY GEORGE A. BARTON BBT.!I' IIAWB COLLliOB N writing the article "Demons, Angels, and Spirits I (Hebrew)" for Hastings' Encgclopcedia of Religi<m mul Ethica, considerable material was gathered on the names of individual spirits which the scope of the article- a part of an article on the spirits of all nations-made it impossi ble to use. The material is, accordingly, presented here. In the earlier time the various angels and demons in which the Hebrews believed were not sufficiently personal to bear individual names. Apart from Satan, Azazel, Rahab, Levia than, and, p<>&~ibly, Lilith, we find only names for classes of beings. A great change is traceable in the literature of the second century B.c. and the centuries which followed. Proper names were then bestowed upon many spirits both good and bad. Two of these names, Gabriel and Michael, occur in the Book of Daniel (816 10 13, 21), but the apocryphal literature affords a considerable number. The following is an alphabetical list of the good angels whose names are given in the various books: Adnlrel (according to Schwab 1 = .,ac-u-,ac =.,lf'l"m, 'my Lord is God'), an angel who, as second in rank, controls a fourth of the year or one of the seasons (Eth. En. 82 u). The name is a variant of Narel (see below), which appears in the same context. Anyalalyur, an angel who, according to Dillmann's text of En. -

Buffy and Angel

buffy and angel PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Fri, 01 Jul 2011 03:42:14 UTC Contents Articles buffy and angel 1 Buffy the Vampire Slayer (film) 1 Buffy the Vampire Slayer (TV series) 5 Buffy the Vampire Slayer (season 1) 25 Buffy the Vampire Slayer (season 2) 30 Buffy the Vampire Slayer (season 3) 37 Angel (TV series) 42 Buffy the Vampire Slayer (season 4) 58 Angel (season 1) 65 Buffy the Vampire Slayer (season 5) 72 Angel (season 2) 78 Angel (season 3) 84 Buffy the Vampire Slayer (season 6) 90 Buffy the Vampire Slayer (season 7) 97 Angel (season 4) 103 Angel (season 5) 110 Buffy the Vampire Slayer Season Eight 118 References Article Sources and Contributors 131 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 133 Article Licenses License 134 1 buffy and angel Buffy the Vampire Slayer (film) Buffy the Vampire Slayer Theatrical release poster Directed by Fran Rubel Kuzui Produced by Howard Rosenman Written by Joss Whedon Starring Kristy Swanson Donald Sutherland Paul Reubens Rutger Hauer Luke Perry Music by Carter Burwell Cinematography James Hayman Editing by Jill Savitt Distributed by 20th Century Fox Release date(s) July 31, 1992 Running time 86 minutes Country United States Language English Budget $7 million Gross revenue $16,624,456 Buffy the Vampire Slayer is a 1992 American action/comedy/horror film about a Valley girl cheerleader named Buffy (Kristy Swanson) who learns that it is her fate to hunt vampires. The original script for the film was written by Joss Whedon, who later created the darker and more acclaimed TV series of the same name starring Sarah Michelle Gellar as Buffy. -

Instruction Manual

MULTIPURPOSE EGG SHAPED DECISIVE WEAPON Instruction Manual E©khara ©BANDAI,WiZVATCHI 6-years old and above ● Do not wash the product in the clothes pocket. ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● Product Details The Angel Awakens Ball Pull on the tab from the bottom of 【SETTING THE TIMER】 Front chain the casing. Use button (A) to set the Casing Monitor ▶The timer setting screen will time in order of “hours” → (Body) (LCD screen) appear aer a long beep. “minutes”. Use button (B) to execute the changes. Press on the holder 【HOW TO RESET】 Battery Press button (C) to return with the ball chain in Press on the reset switch on the back tab a step back. place to remove the of the casing with a tipped object. A button B button C button ball chain. Reset 【THE ANGEL AWAKENS】 Hardened Select Execute Cancel ▶A long beep will play. switch Once the timer is set, the with Train Timer display Confirm call bakelite ※Do not press hard on the reset switch Angel will appear as a fetus using pointed objects, such as mechanical hardened with bakelite, pencils, to prevent damage to the device. and will immediately break Back Hook the ball chain ※Please press the reset switch aer out of its containment to Battery Reset inside the clasp, and changing batteries. begin its growth. Awakens cover switch pull on the chain to lock the ball chain to the clasp. ※Please go through the【 HOW TO RESET】 instructions if the device or screen doesn’t function properly. Push lock ※There is no save function to the product. Please be warned that changing batteries or going ※Images do not represent the final product.