The Depth of Simple Craters and the Permanent Shadow They Cast: Evidence for Ice on Mercury but Not on the Moon L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ices on Mercury: Chemistry of Volatiles in Permanently Cold Areas of Mercury’S North Polar Region

Icarus 281 (2017) 19–31 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Icarus journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/icarus Ices on Mercury: Chemistry of volatiles in permanently cold areas of Mercury’s north polar region ∗ M.L. Delitsky a, , D.A. Paige b, M.A. Siegler c, E.R. Harju b,f, D. Schriver b, R.E. Johnson d, P. Travnicek e a California Specialty Engineering, Pasadena, CA b Dept of Earth, Planetary and Space Sciences, University of California, Los Angeles, CA c Planetary Science Institute, Tucson, AZ d Dept of Engineering Physics, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA e Space Sciences Laboratory, University of California, Berkeley, CA f Pasadena City College, Pasadena, CA a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: Observations by the MESSENGER spacecraft during its flyby and orbital observations of Mercury in 2008– Received 3 January 2016 2015 indicated the presence of cold icy materials hiding in permanently-shadowed craters in Mercury’s Revised 29 July 2016 north polar region. These icy condensed volatiles are thought to be composed of water ice and frozen Accepted 2 August 2016 organics that can persist over long geologic timescales and evolve under the influence of the Mercury Available online 4 August 2016 space environment. Polar ices never see solar photons because at such high latitudes, sunlight cannot Keywords: reach over the crater rims. The craters maintain a permanently cold environment for the ices to persist. Mercury surface ices magnetospheres However, the magnetosphere will supply a beam of ions and electrons that can reach the frozen volatiles radiolysis and induce ice chemistry. -

Bepicolombo - a Mission to Mercury

BEPICOLOMBO - A MISSION TO MERCURY ∗ R. Jehn , J. Schoenmaekers, D. Garc´ıa and P. Ferri European Space Operations Centre, ESA/ESOC, Darmstadt, Germany ABSTRACT BepiColombo is a cornerstone mission of the ESA Science Programme, to be launched towards Mercury in July 2014. After a journey of nearly 6 years two probes, the Magneto- spheric Orbiter (JAXA) and the Planetary Orbiter (ESA) will be separated and injected into their target orbits. The interplanetary trajectory includes flybys at the Earth, Venus (twice) and Mercury (four times), as well as several thrust arcs provided by the solar electric propulsion module. At the end of the transfer a gravitational capture at the weak stability boundary is performed exploiting the Sun gravity. In case of a failure of the orbit insertion burn, the spacecraft will stay for a few revolutions in the weakly captured orbit. The arrival conditions are chosen such that backup orbit insertion manoeuvres can be performed one, four or five orbits later with trajectory correction manoeuvres of less than 15 m/s to compensate the Sun perturbations. Only in case that no manoeuvre can be performed within 64 days (5 orbits) after the nominal orbit insertion the spacecraft will leave Mercury and the mission will be lost. The baseline trajectory has been designed taking into account all operational constraints: 90-day commissioning phase without any thrust; 30-day coast arcs before each flyby (to allow for precise navigation); 7-day coast arcs after each flyby; 60-day coast arc before orbit insertion; Solar aspect angle constraints and minimum flyby altitudes (300 km at Earth and Venus, 200 km at Mercury). -

The Search for Another Earth – Part II

GENERAL ARTICLE The Search for Another Earth – Part II Sujan Sengupta In the first part, we discussed the various methods for the detection of planets outside the solar system known as the exoplanets. In this part, we will describe various kinds of exoplanets. The habitable planets discovered so far and the present status of our search for a habitable planet similar to the Earth will also be discussed. Sujan Sengupta is an 1. Introduction astrophysicist at Indian Institute of Astrophysics, Bengaluru. He works on the The first confirmed exoplanet around a solar type of star, 51 Pe- detection, characterisation 1 gasi b was discovered in 1995 using the radial velocity method. and habitability of extra-solar Subsequently, a large number of exoplanets were discovered by planets and extra-solar this method, and a few were discovered using transit and gravi- moons. tational lensing methods. Ground-based telescopes were used for these discoveries and the search region was confined to about 300 light-years from the Earth. On December 27, 2006, the European Space Agency launched 1The movement of the star a space telescope called CoRoT (Convection, Rotation and plan- towards the observer due to etary Transits) and on March 6, 2009, NASA launched another the gravitational effect of the space telescope called Kepler2 to hunt for exoplanets. Conse- planet. See Sujan Sengupta, The Search for Another Earth, quently, the search extended to about 3000 light-years. Both Resonance, Vol.21, No.7, these telescopes used the transit method in order to detect exo- pp.641–652, 2016. planets. Although Kepler’s field of view was only 105 square de- grees along the Cygnus arm of the Milky Way Galaxy, it detected a whooping 2326 exoplanets out of a total 3493 discovered till 2Kepler Telescope has a pri- date. -

Mariner to Mercury, Venus and Mars

NASA Facts National Aeronautics and Space Administration Jet Propulsion Laboratory California Institute of Technology Pasadena, CA 91109 Mariner to Mercury, Venus and Mars Between 1962 and late 1973, NASA’s Jet carry a host of scientific instruments. Some of the Propulsion Laboratory designed and built 10 space- instruments, such as cameras, would need to be point- craft named Mariner to explore the inner solar system ed at the target body it was studying. Other instru- -- visiting the planets Venus, Mars and Mercury for ments were non-directional and studied phenomena the first time, and returning to Venus and Mars for such as magnetic fields and charged particles. JPL additional close observations. The final mission in the engineers proposed to make the Mariners “three-axis- series, Mariner 10, flew past Venus before going on to stabilized,” meaning that unlike other space probes encounter Mercury, after which it returned to Mercury they would not spin. for a total of three flybys. The next-to-last, Mariner Each of the Mariner projects was designed to have 9, became the first ever to orbit another planet when two spacecraft launched on separate rockets, in case it rached Mars for about a year of mapping and mea- of difficulties with the nearly untried launch vehicles. surement. Mariner 1, Mariner 3, and Mariner 8 were in fact lost The Mariners were all relatively small robotic during launch, but their backups were successful. No explorers, each launched on an Atlas rocket with Mariners were lost in later flight to their destination either an Agena or Centaur upper-stage booster, and planets or before completing their scientific missions. -

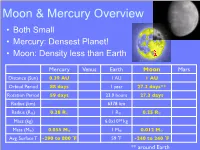

Moon & Mercury Overview

Moon & Mercury Overview • Both Small • Mercury: Densest Planet! • Moon: Density less than Earth Mercury Venus Earth Moon Mars Distance (Sun) 0.39 AU 1 AU 1 AU Orbital Period 88 days 1 year 27.3 days** Rotation Period 59 days 23.9 hours 27.3 days Radius (km) 6378 km Radius (R⊕) 0.38 R⊕ 1 R⊕ 0.25 R⊕ Mass (kg) 6.0x1024 kg Mass (M⊕) 0.055 M⊕ 1 M⊕ 0.012 M⊕ Avg. Surface T -290 to 800 F̊ 59 F̊ -240 to 240 F̊ ** around Earth Lunar Surface • Cratered – 30,000 big (> 1km) – millions of smaller craters MercurianMercury Surface - Surface Features Messenger Images Era of Heavy Bombardment Period of intense impacts in the inner S.S. by leftover planetesimals from outer S.S. 4.1-3.8 billion yrs ago affects all Terr. planets Lunar Surface • Dark Maria (“Seas”) • Lighter Highlands (“Lands”, Terrae) Lunar Surface • Maria What’s different? Why? • Highlands Apollo Lunar Surface Maria: smooth, flat, fewer craters Highlands: VERY cratered Maria have been resurfaced! Maria Formation After Heavy Bombardment Volcanic Activity caused by heat from radioactive decay flooded old craters Dating the Lunar Surface Crater Counting! Which is oldest? The Moon - Space Exploration • Luna 3 (Russia), 1959 Luna 3 farside • NASA Rangers (Impactors), 1961-1965 • Orbiters (99% mapped), 1966-1967 • Surveyors (landers), 1966-1968 • Apollo (manned), 1968-1972 • Clementine (Multi-wavel. mapping), 1994 • Prospector (polar orbiter), 1998 • SMART-1 (ESA Impactor), 2003-2006 • Kaguya (Japan), 2007- Prospector • Chang-e 1 (China), 2007- • Chandrayaan (India), 2008- Orbiter • Lunar Recon. -

The Composition of Planetary Atmospheres 1

The Composition of Planetary Atmospheres 1 All of the planets in our solar system, and some of its smaller bodies too, have an outer layer of gas we call the atmosphere. The atmosphere usually sits atop a denser, rocky crust or planetary core. Atmospheres can extend thousands of kilometers into space. The table below gives the name of the kind of gas found in each object’s atmosphere, and the total mass of the atmosphere in kilograms. The table also gives the percentage of the atmosphere composed of the gas. Object Mass Carbon Nitrogen Oxygen Argon Methane Sodium Hydrogen Helium Other (kilograms) Dioxide Sun 3.0x1030 71% 26% 3% Mercury 1000 42% 22% 22% 6% 8% Venus 4.8x1020 96% 4% Earth 1.4x1021 78% 21% 1% <1% Moon 100,000 70% 1% 29% Mars 2.5x1016 95% 2.7% 1.6% 0.7% Jupiter 1.9x1027 89.8% 10.2% Saturn 5.4x1026 96.3% 3.2% 0.5% Titan 9.1x1018 97% 2% 1% Uranus 8.6x1025 2.3% 82.5% 15.2% Neptune 1.0x1026 1.0% 80% 19% Pluto 1.3x1014 8% 90% 2% Problem 1 – Draw a pie graph (circle graph) that shows the atmosphere constituents for Mars and Earth. Problem 2 – Draw a pie graph that shows the percentage of Nitrogen for Venus, Earth, Mars, Titan and Pluto. Problem 3 – Which planet has the atmosphere with the greatest percentage of Oxygen? Problem 4 – Which planet has the atmosphere with the greatest number of kilograms of oxygen? Problem 5 – Compare and contrast the objects with the greatest percentage of hydrogen, and the least percentage of hydrogen. -

First Look at Mercury

PLANETARY SCIENCE Mariner 10 was launched to Mercury by way of Venus on November 3, 1973. It was not the first probe to visit Venus. Both the United States and the Soviet Union previously have sent probes to that mysterious, cloud-shrouded planet. However, Mariner 10 was the first to photographically explore the close-up appearance of the planet, and did so both in visibIe and in ultraviolet light. And Mariner 10 was the first probe of any kind to penetrate interplanetary space beyond the orbit of Venus and to achieve a close look at the planet Mercury. First Look Why go to Mercury? Who needs it? There basically are two kinds of reasons. The first is simple and profound and at Mercury difficult to quantify: The very act of exploration is a positive, cultural activity. No one knows what is going to be found. Finding out what Mercury, what Mars, or BRUCE C. MURRAY what the moon is really like, enlarges the consciousness of all the people who partake of that new reality. TV pictures are of special importance because they provide a way both for the scientist to discover features and concepts he could not have imagined and for the public to directly appreciate and participate in the exploration of a new world. Why go to Mercury? Who needs it? But there are more specific scientific objectives as well. For Mercury, the basic-and anomalous-scientific fact is A planetary scientist that it is a very dense planet: It contains a great amount of tells what the voyage mass for its size. -

Mariner 10 Observations of Field-Aligned Currents at Mercury

Planet. Space Sci., Vol. 45, No. 1, pp. 133-141, 1997 Pergamon #I? 1997 Published bv Elsevier Science Ltd P&ted in Great Brit& All rights reserved 0032-0633/97 $17.00+0.00 PII: S0032-0633(96)00104-3 Mariner 10 observations of field-aligned currents at Mercury J. A. Slavin,’ J. C. J. Owen,’ J. E. P. Connerney’ and S. P. Christon ‘Laboratory for Extraterrestrial Physics, NASA/GSFC, Greenbelt, MD 20771, U.S.A. ‘Astronomy Unit, Queen Mary and Westfield College, London, U.K. 3Department of Physics, University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742, U.S.A. Received 5 October 1995; revised 11 April 1996; accepted 13 April 1996 magnetic field at Mercury with a dipole moment of about 300nT R& (see review by Connerney and Ness (1988)). This magnetic field is sufficient to stand-off the average solar wind at an altitude of about 1 RM as depicted in Fig. 1 (see review by Russell et al. (1988)). For the purposes of comparison the diameter of the Earth is indicated at the bottom of the figure (i.e. 1 RE = 6380 km ; 1 RM = 2439 km). Whether or not the solar wind is ever able to compress and/or erode the dayside magnetosphere to the point where solar wind ions could directly impact the surface remains a topic of considerable controversy (Siscoe and Christopher, 1975 ; Slavin and Holzer, 1979 ; Hood and Schubert, 1979; Suess and Goldstein, 1979; Goldstein et al., 1981). Overall, the basic morphology of this small mag- netosphere appears quite similar to that of the Earth. -

Mysterious Mercury Bepicolumbo Heads for the World of Ice and Fire

A Digital Supplement to Astronomy Insights Astronomy Magazine © 2018 Kalmbach Media Mysterious Mercury BepiColumbo Heads for the World of Ice and Fire Dcember 2018 • Astronomy.com Voyage to a world Color explodes from Mercury’s surface in this enhanced-color mosaic taken through several filters. The yellow and orange hues signify relatively young plains likely formed when fluid lavas erupted from volcanoes. Medium- and dark-blue regions are older terrain, while the light-blue and white streaks represent fresh material excavated from relatively recent impacts. ALL IMAGES, UNLESS OTHERWISE NOTED: NASA/JHUAPL/CIW 2 ASTRONOMY INSIGHTS • DECEMBER 2018 A world of both fire and ice, Mercury excites and confounds scientists. The BepiColombo probe aims to make sense of this mysterious world. by Ben Evans of extremesWWW.ASTRONOMY.COM 3 Mercury is a land of contrasts. The solar system’s smallest planet boasts the largest core relative to its size. Temperatures at noon can soar as high as 800 degrees Fahrenheit (425 degrees Celsius) — hot enough to melt lead — but dip as low as –290 F (–180 C) before dawn. Mercury resides nearest the Sun, and it has the most eccentric orbit. At its closest, the planet lies only 29 mil- lion miles (46 million kilometers) from the Sun — less than one-third Earth’s distance — but swings out as far as 43 million miles (70 million km). Its rapid movement across our sky earned it a reputation among ancient skywatchers as the fleet-footed messenger of the gods: Italian scientist Giuseppe “Bepi” Colombo helped develop a technique for sending a space Hermes to the Greeks and Mercury to the Romans. -

Sized Exoplanet Thomas Barclay1,2, Jason F

A sub-Mercury-sized exoplanet Thomas Barclay1,2, Jason F. Rowe1,3, Jack J. Lissauer1, Daniel Huber1,4, François Fressin5, Steve B. Howell1, Stephen T. Bryson1, William J. Chaplin6, Jean-Michel Désert5, Eric D. Lopez7, Geoffrey W. Marcy8, Fergal Mullally1,3, Darin Ragozzine5,9, Guillermo Torres5, Elisabeth R. Adams5, Eric Agol10, David Barrado11,12, Sarbani Basu13, Timothy R. Bedding14, Lars A. Buchhave15,16, David Charbonneau5, Jessie L. Christiansen1,3, Jørgen Christensen-Dalsgaard17, David Ciardi18, William D. Cochran19, Andrea K. Dupree5, Yvonne Elsworth6, Mark Everett20, Debra A. Fischer13, Eric B. Ford9, Jonathan J. Fortney7, John C. Geary5, Michael R. Haas1, Rasmus Handberg17, Saskia Hekker6,21, Christopher E. Henze1, Elliott Horch22, Andrew W. Howard23, Roger C. Hunter1, Howard Isaacson8, Jon M. Jenkins1,3, Christoffer Karoff17, Steven D. Kawaler24, Hans Kjeldsen17, Todd C. Klaus25, David W. Latham5, Jie Li1,3, Jorge Lillo-Box12, Mikkel N. Lund17, Mia Lundkvist17, Travis S. Metcalfe26, Andrea Miglio6, Robert L. Morris1,3, Elisa V. Quintana1,3, Dennis Stello14, Jeffrey C. Smith1,3, Martin Still1,2, & Susan E. Thompson1,3 1 NASA Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, CA 94035, USA 2 Bay Area Environmental Research Institute, 596 First St West, Sonoma, CA 95476, USA 3 SETI Institute, 189 Bernardo Ave, Mountain View, CA 94043, USA 4 NASA Postdoctoral Program Fellow 5 Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, 60 Garden Street, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA 6 School of Physics and Astronomy, University of Birmingham, Edgbaston, B15 2TT, UK 7 Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics, University of California, Santa Cruz, CA 95064, USA 8 Department of Astronomy, UC Berkeley, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA 9 Astronomy Department, University of Florida, 211 Bryant Space Sciences Center, Gainesville, FL 32111, USA 10 Department of Astronomy, Box 351580, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195, USA 11 Calar Alto Observatory, Centro Astronómico Hispano Alemán, C/ Jesús Durbán Remón, E- 04004 Almería, Spain 12 Depto. -

Aerospace Micro-Lesson

AIAA AEROSPACE M ICRO-LESSON Easily digestible Aerospace Principles revealed for K-12 Students and Educators. These lessons will be sent on a bi-weekly basis and allow grade-level focused learning. - AIAA STEM K-12 Committee. THE MARINER PROJECT Started less than five years after the first launch of rockets into orbit, the Project Mariner was the United States’ first attempt to send a spacecraft to another planet. Between 1962 and 1975, Project Mariner involved the launch of ten unmanned spacecraft, seven of them successfully, to the other inner planets of the Solar System. You can find an overview of the project at NASA’s Science web site. GRADES K-2 Astronomy has always been about looking at things from a distance. For centuries and longer, stars and planets were simply points of light in the sky, most of them stationary and a few of them moving. (In fact, the word “planet” is derived from the Greek word “planetes,” which means “wanderer.”) The invention of the telescope changed the view of planets from wandering points of light to bodies that move around the Sun, but even the best telescopes could not distinguish features smaller than a mile across on the moon and several tens of miles across on even the closest planets. The space program changed this. By sending spacecraft to visit the moon and the planets, scientists were able to view these bodies from comparatively close up and see them in much greater detail. This revolutionized solar system astronomy and gave birth to a new science, “planetary science.” Planetary science joins the fields of astronomy, geology, meteorology, and others together into a unified study of the planets. -

Rembrandt Impact Basin on Mercury: Determining the Origin of Low- and High- Albedo Smooth Plains

46th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (2015) 1128.pdf REMBRANDT IMPACT BASIN ON MERCURY: DETERMINING THE ORIGIN OF LOW- AND HIGH- ALBEDO SMOOTH PLAINS. J. L. Whitten1 and J. W. Head2, 1Center for Earth and Planetary Studies, Smithsonian Institution, MRC 315, PO Box 37012, Washington, DC 20013-7012 ([email protected]), 2Dept. of Earth, Environmental and Planetary Sciences, Brown University, Providence, RI 02912. Introduction: Rembrandt impact basin (~715 km plains within and around Rembrandt basin. The bound- in diameter) is one the largest and most well-preserved aries of the different smooth plains deposits were impact basins on Mercury [1]. Crater density measure- mapped using both an MDIS 750 nm albedo mosaic ments indicate that Rembrandt is comparable in age to and a high-incidence angle map. The high-incidence the Caloris impact basin, the largest and also one of the angle map was helpful in discerning the texture of sur- youngest basins on Mercury [e.g., 2, 3]. The basin rim- faces because the low sun angle creates long shadows crest is visible and several massifs define an inner ring that accentuate the morphology of lower slopes and approximately 450 km in diameter. A second inner ring smaller surface features. Areal crater density values, is suggested by a circle of wrinkle ridges in the inner- reported as N(20) [13], for each of the defined plains most part of the impact basin [2]. units were calculated to determine the relative stratig- Rembrandt basin is both surrounded by and con- raphy of smooth plains deposits and the impact basin tains smooth plains deposits of varying albedo.