Community Classification and Nomenclature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

California Native Grasses

S EED & S UPPLIES FOR N O R T H E R N C ALIFORNIA CALIFORNIA NATIVE GRASSES All grasses are grown and/or collected from California sources. Custom mixes are available. CONTACT US for further information and ask about our collecting & producing seed for you. *Multiple types available Genus Species Common Name Achnatherum occidentalis Western Needlegrass Agrostis exerata Native Spiked Bentgrass Agrostis pallens Thingrass Bromus carinatus* California Bromegrass Bromus maritimus Maritime Brome Danthonia californica California Oatgrass Deschampsia caespitosa* Tufted Hairgrass Deschampsia caespitosa var. holciformis California Hairgrass Deschampsia elongatum Slender Hairgrass Elymus elymoides* Bottlebrush Squirreltail Elymus glaucus* Blue Wild Rye Elymus multisetus Big Squirreltail Elymus trachycaulum var. Yolo* California Slender Wheatgrass Festuca californica California Fescue Festuca idahoensis* Idaho Fescue Festuca occidentalis* Western Fescue/Mokelumne Blue Festuca rubra, Molate Blue Molate Blue Fescue Festuca rubra, Molate Molate Red Fescue Hordeum brachyantherum* Meadow Barley Hordeum californicum California Barley & Prostrate form Hordeum depressum Alkali Barley Koeleria macrantha Junegrass Leymus triticoides* Creeping Wild Rye, Rio Melica californica/M. imperfect California/Coast Range Oniongrass Muhlenbergia microsperma Littleseed Deergrass Nassella cernua Nodding Needlegrass Muhlenbergia rigens Deergrass Nassella cernua* Nodding Needlegrass 533 HAWTHORNE PLACE • LIVERMORE, CA 94550 • WWW.PCSEED.COM • 925.373.4417 • FAX 925.373.6855 UP D A T E D O N 4 / 2 / 1 0 A T 4 :0 0 PM CALNATGRASS V- AP 1 0 1 0 . DOC P A GE 1 S EED & S UPPLIES FOR N O R T H E R N C ALIFORNIA Nassella lepida* Foothill Stipa Nassella pulchra* Purple Needlegrass Pleuropogon californica Annual Semaphoregrass Poa secunda Pine Bluegrass Vulpia microstachys Three Weeks Fescue 533 HAWTHORNE PLACE • LIVERMORE, CA 94550 • WWW.PCSEED.COM • 925.373.4417 • FAX 925.373.6855 UP D A T E D O N 4 / 2 / 1 0 A T 4 :0 0 PM CALNATGRASS V- AP 1 0 1 0 . -

Vascular Plants at Fort Ross State Historic Park

19005 Coast Highway One, Jenner, CA 95450 ■ 707.847.3437 ■ [email protected] ■ www.fortross.org Title: Vascular Plants at Fort Ross State Historic Park Author(s): Dorothy Scherer Published by: California Native Plant Society i Source: Fort Ross Conservancy Library URL: www.fortross.org Fort Ross Conservancy (FRC) asks that you acknowledge FRC as the source of the content; if you use material from FRC online, we request that you link directly to the URL provided. If you use the content offline, we ask that you credit the source as follows: “Courtesy of Fort Ross Conservancy, www.fortross.org.” Fort Ross Conservancy, a 501(c)(3) and California State Park cooperating association, connects people to the history and beauty of Fort Ross and Salt Point State Parks. © Fort Ross Conservancy, 19005 Coast Highway One, Jenner, CA 95450, 707-847-3437 .~ ) VASCULAR PLANTS of FORT ROSS STATE HISTORIC PARK SONOMA COUNTY A PLANT COMMUNITIES PROJECT DOROTHY KING YOUNG CHAPTER CALIFORNIA NATIVE PLANT SOCIETY DOROTHY SCHERER, CHAIRPERSON DECEMBER 30, 1999 ) Vascular Plants of Fort Ross State Historic Park August 18, 2000 Family Botanical Name Common Name Plant Habitat Listed/ Community Comments Ferns & Fern Allies: Azollaceae/Mosquito Fern Azo/la filiculoides Mosquito Fern wp Blechnaceae/Deer Fern Blechnum spicant Deer Fern RV mp,sp Woodwardia fimbriata Giant Chain Fern RV wp Oennstaedtiaceae/Bracken Fern Pleridium aquilinum var. pubescens Bracken, Brake CG,CC,CF mh T Oryopteridaceae/Wood Fern Athyrium filix-femina var. cyclosorum Western lady Fern RV sp,wp Dryopteris arguta Coastal Wood Fern OS op,st Dryopteris expansa Spreading Wood Fern RV sp,wp Polystichum munitum Western Sword Fern CF mh,mp Equisetaceae/Horsetail Equisetum arvense Common Horsetail RV ds,mp Equisetum hyemale ssp.affine Common Scouring Rush RV mp,sg Equisetum laevigatum Smooth Scouring Rush mp,sg Equisetum telmateia ssp. -

Grasses Plant List

Grasses Plant List California Botanical Name Common Name Water Use Native Aristida purpurea purple three-awn Very Low X Arundinaria gigantea cane reed Low Bothriochloa barbinodis cane bluestem Low X Bouteloua curtipendula sideoats grama Low X Bouteloua gracilis, cvs. blue grama Low X Briza media quaking grass Low Calamagrostis x acutiflora cvs., e.g. Karl feather reed grass Low Foerster Cortaderia selloana cvs. pampas grass Low Deschampsia cespitosa, cvs. tufted hairgrass Low X Distichlis spicata (marsh, reveg.) salt grass Very Low X Elymus condensatus, cvs. (Leymus giant wild rye Low X condensatus) Elymus triticoides (Leymus triticoides) creeping wild rye Low X Eragrostis elliottii 'Tallahassee Sunset' Elliott's lovegrass Low Eragrostis spectabilis purple love grass Low Festuca glauca blue fescue Low Festuca idahoensis, cvs. Idaho fescue Low X Festuca mairei Maire's fescue Low Helictotrichon sempervirens, cvs. blue oat grass Low Hordeum brachyantherum Meadow barley Very Low X Koeleria macrantha (cristata) June grass Low X Melica californica oniongrass Very Low X Melica imperfecta coast range onion grass Very Low X Melica torreyana Torrey's melic Very Low X Muhlenbergia capillaris, cvs. hairy awn muhly Low Muhlenbergia dubia pine muhly Low Muhlenbergia filipes purply muhly Low Muhlenbergia lindheimeri Lindheimer muhly Low Muhlenbergia pubescens soft muhly Low Muhlenbergia rigens deer grass Low X Nassella gigantea giant needle grass Low Panicum spp. panic grass Low Panicum virgatum, cvs. switch grass Low Pennisetum alopecuroides, cvs. -

Introductory Grass Identification Workshop University of Houston Coastal Center 23 September 2017

Broadleaf Woodoats (Chasmanthium latifolia) Introductory Grass Identification Workshop University of Houston Coastal Center 23 September 2017 1 Introduction This 5 hour workshop is an introduction to the identification of grasses using hands- on dissection of diverse species found within the Texas middle Gulf Coast region (although most have a distribution well into the state and beyond). By the allotted time period the student should have acquired enough knowledge to identify most grass species in Texas to at least the genus level. For the sake of brevity grass physiology and reproduction will not be discussed. Materials provided: Dried specimens of grass species for each student to dissect Jewelry loupe 30x pocket glass magnifier Battery-powered, flexible USB light Dissecting tweezer and needle Rigid white paper background Handout: - Grass Plant Morphology - Types of Grass Inflorescences - Taxonomic description and habitat of each dissected species. - Key to all grass species of Texas - References - Glossary Itinerary (subject to change) 0900: Introduction and house keeping 0905: Structure of the course 0910: Identification and use of grass dissection tools 0915- 1145: Basic structure of the grass Identification terms Dissection of grass samples 1145 – 1230: Lunch 1230 - 1345: Field trip of area and collection by each student of one fresh grass species to identify back in the classroom. 1345 - 1400: Conclusion and discussion 2 Grass Structure spikelet pedicel inflorescence rachis culm collar internode ------ leaf blade leaf sheath node crown fibrous roots 3 Grass shoot. The above ground structure of the grass. Root. The below ground portion of the main axis of the grass, without leaves, nodes or internodes, and absorbing water and nutrients from the soil. -

The Jepson Manual: Vascular Plants of California, Second Edition Supplement II December 2014

The Jepson Manual: Vascular Plants of California, Second Edition Supplement II December 2014 In the pages that follow are treatments that have been revised since the publication of the Jepson eFlora, Revision 1 (July 2013). The information in these revisions is intended to supersede that in the second edition of The Jepson Manual (2012). The revised treatments, as well as errata and other small changes not noted here, are included in the Jepson eFlora (http://ucjeps.berkeley.edu/IJM.html). For a list of errata and small changes in treatments that are not included here, please see: http://ucjeps.berkeley.edu/JM12_errata.html Citation for the entire Jepson eFlora: Jepson Flora Project (eds.) [year] Jepson eFlora, http://ucjeps.berkeley.edu/IJM.html [accessed on month, day, year] Citation for an individual treatment in this supplement: [Author of taxon treatment] 2014. [Taxon name], Revision 2, in Jepson Flora Project (eds.) Jepson eFlora, [URL for treatment]. Accessed on [month, day, year]. Copyright © 2014 Regents of the University of California Supplement II, Page 1 Summary of changes made in Revision 2 of the Jepson eFlora, December 2014 PTERIDACEAE *Pteridaceae key to genera: All of the CA members of Cheilanthes transferred to Myriopteris *Cheilanthes: Cheilanthes clevelandii D. C. Eaton changed to Myriopteris clevelandii (D. C. Eaton) Grusz & Windham, as native Cheilanthes cooperae D. C. Eaton changed to Myriopteris cooperae (D. C. Eaton) Grusz & Windham, as native Cheilanthes covillei Maxon changed to Myriopteris covillei (Maxon) Á. Löve & D. Löve, as native Cheilanthes feei T. Moore changed to Myriopteris gracilis Fée, as native Cheilanthes gracillima D. -

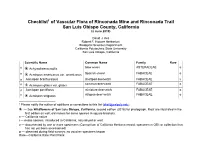

Rinconada Checklist-02Jun19

Checklist1 of Vascular Flora of Rinconada Mine and Rinconada Trail San Luis Obispo County, California (2 June 2019) David J. Keil Robert F. Hoover Herbarium Biological Sciences Department California Polytechnic State University San Luis Obispo, California Scientific Name Common Name Family Rare n ❀ Achyrachaena mollis blow wives ASTERACEAE o n ❀ Acmispon americanus var. americanus Spanish-clover FABACEAE o n Acmispon brachycarpus shortpod deervetch FABACEAE v n ❀ Acmispon glaber var. glaber common deerweed FABACEAE o n Acmispon parviflorus miniature deervetch FABACEAE o n ❀ Acmispon strigosus strigose deer-vetch FABACEAE o 1 Please notify the author of additions or corrections to this list ([email protected]). ❀ — See Wildflowers of San Luis Obispo, California, second edition (2018) for photograph. Most are illustrated in the first edition as well; old names for some species in square brackets. n — California native i — exotic species, introduced to California, naturalized or waif. v — documented by one or more specimens (Consortium of California Herbaria record; specimen in OBI; or collection that has not yet been accessioned) o — observed during field surveys; no voucher specimen known Rare—California Rare Plant Rank Scientific Name Common Name Family Rare n Acmispon wrangelianus California deervetch FABACEAE v n ❀ Acourtia microcephala sacapelote ASTERACEAE o n ❀ Adelinia grandis Pacific hound's tongue BORAGINACEAE v n ❀ Adenostoma fasciculatum var. chamise ROSACEAE o fasciculatum n Adiantum jordanii California maidenhair fern PTERIDACEAE o n Agastache urticifolia nettle-leaved horsemint LAMIACEAE v n ❀ Agoseris grandiflora var. grandiflora large-flowered mountain-dandelion ASTERACEAE v n Agoseris heterophylla var. cryptopleura annual mountain-dandelion ASTERACEAE v n Agoseris heterophylla var. heterophylla annual mountain-dandelion ASTERACEAE o i Aira caryophyllea silver hairgrass POACEAE o n Allium fimbriatum var. -

Plant Species on Salt-Affected Soil at Cheyenne Bottoms, Kansas

TRANSACTIONS OF THE KANSAS Vol. 109, no. 3/4 ACADEMY OF SCIENCE p. 207-213 (2006) Plant species on salt-affected soil at Cheyenne Bottoms, Kansas TODD A. ASCHENBACH1 AND KELLY KINDSCHER2 1. Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas 66045-2106 ([email protected]) 2. Kansas Biological Survey, University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas 66047-3729 ([email protected]). Soil salinity and vegetative cover were investigated at Cheyenne Bottoms Preserve, Kansas in an effort to identify and document the plant species present on naturally occurring salt- and sodium-affected soil. Soil salinity (as indicated by electrical conductivity, ECe) and sodium adsorption ratio (SAR) were measured from nine soil samples collected to a depth of 20 cm in June 1998. Vegetative cover was visually estimated in June and September 1998. A total of 20 plant species were encountered at five soil sampling locations on soils classified as saline, saline-sodic, or sodic. Dominant species observed include Agropyron smithii, Distichlis spicata, Euphorbia geyeri, Poa arida, and Sporobolus airoides. While most species encountered during this study exhibited greater vegetative cover on non-saline soils, all of the dominant species, except A. smithii, exhibited greater cover on salt-affected soil compared to non- saline soil. Comparable salinity levels and species found in areas that have been degraded through oil and gas production activities suggest that the dominant species observed in this study deserve further attention as potential candidates for the restoration of salt-affected areas. Key Words: brine contamination, Cheyenne Bottoms, restoration, saline-sodic, salinity, salt tolerance. INTRODUCTION osmotic stress, ion toxicity or decreased absorption of essential nutrients (Läuchli and Salt-affected soils are commonly found in arid Epstein 1990). -

Fort Ord Natural Reserve Plant List

UCSC Fort Ord Natural Reserve Plants Below is the most recently updated plant list for UCSC Fort Ord Natural Reserve. * non-native taxon ? presence in question Listed Species Information: CNPS Listed - as designated by the California Rare Plant Ranks (formerly known as CNPS Lists). More information at http://www.cnps.org/cnps/rareplants/ranking.php Cal IPC Listed - an inventory that categorizes exotic and invasive plants as High, Moderate, or Limited, reflecting the level of each species' negative ecological impact in California. More information at http://www.cal-ipc.org More information about Federal and State threatened and endangered species listings can be found at https://www.fws.gov/endangered/ (US) and http://www.dfg.ca.gov/wildlife/nongame/ t_e_spp/ (CA). FAMILY NAME SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME LISTED Ferns AZOLLACEAE - Mosquito Fern American water fern, mosquito fern, Family Azolla filiculoides ? Mosquito fern, Pacific mosquitofern DENNSTAEDTIACEAE - Bracken Hairy brackenfern, Western bracken Family Pteridium aquilinum var. pubescens fern DRYOPTERIDACEAE - Shield or California wood fern, Coastal wood wood fern family Dryopteris arguta fern, Shield fern Common horsetail rush, Common horsetail, field horsetail, Field EQUISETACEAE - Horsetail Family Equisetum arvense horsetail Equisetum telmateia ssp. braunii Giant horse tail, Giant horsetail Pentagramma triangularis ssp. PTERIDACEAE - Brake Family triangularis Gold back fern Gymnosperms CUPRESSACEAE - Cypress Family Hesperocyparis macrocarpa Monterey cypress CNPS - 1B.2, Cal IPC -

APPENDIX D Biological Technical Report

APPENDIX D Biological Technical Report CarMax Auto Superstore EIR BIOLOGICAL TECHNICAL REPORT PROPOSED CARMAX AUTO SUPERSTORE PROJECT CITY OF OCEANSIDE, SAN DIEGO COUNTY, CALIFORNIA Prepared for: EnviroApplications, Inc. 2831 Camino del Rio South, Suite 214 San Diego, California 92108 Contact: Megan Hill 619-291-3636 Prepared by: 4629 Cass Street, #192 San Diego, California 92109 Contact: Melissa Busby 858-334-9507 September 29, 2020 Revised March 23, 2021 Biological Technical Report CarMax Auto Superstore TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................ 3 SECTION 1.0 – INTRODUCTION ................................................................................... 6 1.1 Proposed Project Location .................................................................................... 6 1.2 Proposed Project Description ............................................................................... 6 SECTION 2.0 – METHODS AND SURVEY LIMITATIONS ............................................ 8 2.1 Background Research .......................................................................................... 8 2.2 General Biological Resources Survey .................................................................. 8 2.3 Jurisdictional Delineation ...................................................................................... 9 2.3.1 U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Jurisdiction .................................................... 9 2.3.2 Regional Water Quality -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Understanding The

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Understanding the Effects of Floral Density on Flower Visitation Rates and Species Composition of Flower Visitors A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Evolution, Ecology and Organismal Biology by Carla Jean Essenberg June 2012 Dissertation Committee: Dr. John T. Rotenberry, Chairperson Dr. Kurt E. Anderson Dr. Richard A. Redak Copyright by Carla Jean Essenberg 2012 The Dissertation of Carla Jean Essenberg is approved: _________________________________________________ _________________________________________________ _________________________________________________ Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements I thank my advisor, John Rotenberry, and my committee members Kurt Anderson and Rick Redak for advice provided throughout the development and writing of my dissertation. I am grateful to Sarah Schmits, Jennifer Howard, Matthew Poonamallee, Emily Bergmann, and Susan Bury for their assistance in collecting field data. Margaret Essenberg, Nick Waser, and five anonymous reviewers provided helpful comments on individual chapters of this dissertation. I also thank Paul Aigner, Doug Yanega, the Univ. of California-Riverside Biology Department Lab Prep staff, Dmitry Maslov, Barbara Walter, Morris and Gina Maduro, Ed Platzer, Rhett Woerly, and the Univ. of Califorina- Riverside Entomology Research Museum for providing advice, equipment, and/or assistance with logistical challenges encountered during data collection. All field data were collected at the UC-Davis Donald and Sylvia McLaughlin Natural Reserve. The work was supported by a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship, a Mildred E. Mathias Graduate Student Research Grant from the Univ. of California Natural Reserve System, and funding from the University of California- Riverside. The material in Chapter 1 was accepted for publication in the American Naturalist on March 26, 2012. -

References and Appendices

References Ainley, D.G., S.G. Allen, and L.B. Spear. 1995. Off- Arnold, R.A. 1983. Ecological studies on six endan- shore occurrence patterns of marbled murrelets gered butterflies (Lepidoptera: Lycaenidae): in central California. In: C.J. Ralph, G.L. Hunt island biogeography, patch dynamics, and the Jr., M.G. Raphael, and J.F. Piatt, technical edi- design of habitat preserves. University of Cali- tors. Ecology and Conservation of the Marbled fornia Publications in Entomology 99: 1–161. Murrelet. USDA Forest Service, General Techni- Atwood, J.L. 1993. California gnatcatchers and coastal cal Report PSW-152; 361–369. sage scrub: the biological basis for endangered Allen, C.R., R.S. Lutz, S. Demairais. 1995. Red im- species listing. In: J.E. Keeley, editor. Interface ported fire ant impacts on Northern Bobwhite between ecology and land development in Cali- populations. Ecological Applications 5: 632-638. fornia. Southern California Academy of Sciences, Allen, E.B., P.E. Padgett, A. Bytnerowicz, and R.A. Los Angeles; 149–169. Minnich. 1999. Nitrogen deposition effects on Atwood, J.L., P. Bloom, D. Murphy, R. Fisher, T. Scott, coastal sage vegetation of southern California. In T. Smith, R. Wills, P. Zedler. 1996. Principles of A. Bytnerowicz, M.J. Arbaugh, and S. Schilling, reserve design and species conservation for the tech. coords. Proceedings of the international sym- southern Orange County NCCP (Draft of Oc- posium on air pollution and climate change effects tober 21, 1996). Unpublished manuscript. on forest ecosystems, February 5–9, 1996, River- Austin, M. 1903. The Land of Little Rain. University side, CA. -

Edible Seeds and Grains of California Tribes

National Plant Data Team August 2012 Edible Seeds and Grains of California Tribes and the Klamath Tribe of Oregon in the Phoebe Apperson Hearst Museum of Anthropology Collections, University of California, Berkeley August 2012 Cover photos: Left: Maidu woman harvesting tarweed seeds. Courtesy, The Field Museum, CSA1835 Right: Thick patch of elegant madia (Madia elegans) in a blue oak woodland in the Sierra foothills The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its pro- grams and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sex- ual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or a part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write to USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW., Washington, DC 20250–9410, or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Acknowledgments This report was authored by M. Kat Anderson, ethnoecologist, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) and Jim Effenberger, Don Joley, and Deborah J. Lionakis Meyer, senior seed bota- nists, California Department of Food and Agriculture Plant Pest Diagnostics Center. Special thanks to the Phoebe Apperson Hearst Museum staff, especially Joan Knudsen, Natasha Johnson, Ira Jacknis, and Thusa Chu for approving the project, helping to locate catalogue cards, and lending us seed samples from their collections.