Plasma Terminal Half-Life

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1: Clinical Pharmacokinetics 1

1: CLINICAL PHARMACOKINETICS 1 General overview: clinical pharmacokinetics, 2 Pharmacokinetics, 4 Drug clearance (CL), 6 Volume of distribution (Vd), 8 The half-life (t½), 10 Oral availability (F), 12 Protein binding (PB), 14 pH and pharmacokinetics, 16 1 Clinical pharmacokinetics General overview General overview: clinical pharmacokinetics 1 The ultimate aim of drug therapy is to achieve effi cacy without toxicity. This involves achieving a plasma concentration (Cp) within the ‘therapeutic window’, i.e. above the min- imal effective concentration (MEC), but below the minimal toxic concentration (MTC). Clinical pharmacokinetics is about all the factors that determine variability in the Cp and its time-course. The various factors are dealt with in subsequent chapters. Ideal therapeutics: effi cacy without toxicity Minimum Toxic Concentration (MTC) Ideal dosing Minimum Effective Concentration (MEC) Drug concentration Time The graph shows a continuous IV infusion at steady state, where the dose-rate is exactly appropriate for the patient’s clearance (CL). Inappropriate dosing Dosing too high in relation to the patient’s CL – toxicity likely Minimum Toxic Concentration (MTC) Minimum Effective Concentration (MEC) Dosing too low in relation to the Drug concentration patient’s CL – drug may be ineffective Time Some reasons for variation in CL Low CL High CL Normal variation Normal variation Renal impairment Increased renal blood fl ow Genetic poor metabolism Genetic hypermetabolism Liver impairment Enzyme induction Enzyme inhibition Old age/neonate 2 General overview Clinical Pharmacokinetics Pharmacokinetic factors determining ideal therapeutics If immediate effect is needed, a loading dose (LD) must be given to achieve a desired 1 concentration. The LD is determined by the volume of distribution (Vd). -

Pharmacokinetics, Biodistribution, and Pharmacodynamics of Drug Delivery Systems

JPET Fast Forward. Published on March 5, 2019 as DOI: 10.1124/jpet.119.257113 This article has not been copyedited and formatted. The final version may differ from this version. JPET # 257113 Title: Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Properties of Drug Delivery Systems Authors: Patrick M. Glassman, Vladimir R. Muzykantov Affiliation: Department of Systems Pharmacology and Translational Therapeutics, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania Address: 3400 Civic Center Boulevard, Bldg 421, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-5158, United States Downloaded from jpet.aspetjournals.org at ASPET Journals on September 24, 2021 1 JPET Fast Forward. Published on March 5, 2019 as DOI: 10.1124/jpet.119.257113 This article has not been copyedited and formatted. The final version may differ from this version. JPET # 257113 Running Title: PK/PD Properties of Drug Delivery Systems Corresponding Authors: Vladimir R. Muzykantov ([email protected], (215) 898-9823) and Patrick M. Glassman ([email protected]) # of Text Pages: 22 # of Tables: 2 # of Figures: 4 Word Count – Abstract: 144 Word Count – Introduction: 350 Word Count – Discussion: N/A Downloaded from Non-Standard Abbreviations: Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Elimination (ADME) Biodistribution (BD) Drug Delivery Systems (DDSs) Enhanced Permeability & Retention (EPR) jpet.aspetjournals.org Gastrointestinal (GI) Intravenously (IV) Neonatal Fc Receptor (FcRn) Monoclonal Antibody (mAb) Reticuloendothelial System (RES) at ASPET Journals on September 24, 2021 Pharmacodynamics (PD) Pharmacokinetics (PK) Physiologically-Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) Subcutaneously (SC) Target-Mediated Drug Disposition (TMDD) Recommended Section: Drug Discovery and Translational Medicine 2 JPET Fast Forward. Published on March 5, 2019 as DOI: 10.1124/jpet.119.257113 This article has not been copyedited and formatted. -

Multidrug-Resistant Gram-Negative Bacteria

Multidrug-Resistant Gram-Negative Bacteria: Trends, Risk Factors, and Treatments A worldwide public health problem, antibiotic resistance leads to treatment-resistant infections associated with prolonged hospitalizations, increased cost, and greater risk for morbidity. Lee S. Engel MD, PhD CASE INTRODUCTION An 80-year-old female nursing home resident with Antibiotics have saved the lives of millions of people a history of dementia, anemia, atrial fibrillation, and have contributed to the major gains in life ex- hypertension, incontinence, and recurrent urinary pectancy over the last century. In US hospitals, 190 tract infections (UTIs), as well as a long-term Foley million doses of antibiotics are administered each catheter, is admitted because she was found to be day.1 Furthermore, more than 133 million courses febrile and less responsive than normal. The patient of antibiotics are prescribed each year for outpatients. has no drug allergies. Upon admission, she has a However, antibiotic use has also resulted in a major temperature of 38.9ºC, heart rate of 92 beats/min, health care challenge—the development and spread and blood pressure of 106/64 mm Hg. The patient of resistant bacteria. Worldwide, antimicrobial resis- opens her eyes to stimuli but does not speak. Aside tance is most evident in diarrheal diseases, respira- from poor dentition and an irregular heart rate, tory tract infections, meningitis, sexually transmitted findings on physical examination, which includes infections, and hospital and health care–acquired in- a pulmonary and abdominal examination, are nor- fections.2 Vancomycin-resistant enterococci, methi- mal. Serum chemistries demonstrate a white blood cillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, multidrug-resis- cell (WBC) count of 11,300 cells/mm3. -

Clinical Pharmacology 1: Phase 1 Studies and Early Drug Development

Clinical Pharmacology 1: Phase 1 Studies and Early Drug Development Gerlie Gieser, Ph.D. Office of Clinical Pharmacology, Div. IV Objectives • Outline the Phase 1 studies conducted to characterize the Clinical Pharmacology of a drug; describe important design elements of and the information gained from these studies. • List the Clinical Pharmacology characteristics of an Ideal Drug • Describe how the Clinical Pharmacology information from Phase 1 can help design Phase 2/3 trials • Discuss the timing of Clinical Pharmacology studies during drug development, and provide examples of how the information generated could impact the overall clinical development plan and product labeling. Phase 1 of Drug Development CLINICAL DEVELOPMENT RESEARCH PRE POST AND CLINICAL APPROVAL 1 DISCOVERY DEVELOPMENT 2 3 PHASE e e e s s s a a a h h h P P P Clinical Pharmacology Studies Initial IND (first in human) NDA/BLA SUBMISSION Phase 1 – studies designed mainly to investigate the safety/tolerability (if possible, identify MTD), pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of an investigational drug in humans Clinical Pharmacology • Study of the Pharmacokinetics (PK) and Pharmacodynamics (PD) of the drug in humans – PK: what the body does to the drug (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion) – PD: what the drug does to the body • PK and PD profiles of the drug are influenced by physicochemical properties of the drug, product/formulation, administration route, patient’s intrinsic and extrinsic factors (e.g., organ dysfunction, diseases, concomitant medications, -

No Slide Title

[email protected] In Silico Drug Interaction of Long-acting # 458 Rilpivirine and Cabotegravir With Rifampin Rajith KR Rajoli1, Paul Curley1, David Back1, Charles Flexner2, Andrew Owen1, Marco Siccardi1 1 - Department of Molecular and Clinical Pharmacology, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, UK 2- Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD, USA Introduction Methods • Physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modelling represents a • Co-administration of anti-TB drugs and many antiretrovirals (ARVs) result mathematical tool to predict DDI magnitude through a detailed • 100 virtual individuals were simulated using Simbiology v.4.3.1, a in important drug-drug interactions (DDIs) understanding of mechanisms underpinning pharmacokinetics product of MATLAB (version 2013b) • Investigation of DDIs between ARVs and anti-TB drugs in individuals can • The objective of this study was to simulate the effect of rifampicin on the • PBPK models were qualified against literature data for oral formulations be complicated by numerous clinical, logistical barriers and also due to pharmacokinetics of cabotegravir and rilpivirine long-acting injectable (LAI) of rifampicin (600 mg OD, at day 6 & 14), cabotegravir and rilpivirine the risk of treatment failure intramuscular (IM) formulations using PBPK modelling (oral, single dose & steady state and IM compared to LATTE-2 studies)1-4 • Loading doses of 800 mg, 900 mg and maintenance doses of 400/800 Results mg, 600/900 mg were used for cabotegravir -

Alcohol Withdrawal

Alcohol withdrawal TERMINOLOGY CLINICAL CLARIFICATION • Alcohol withdrawal may occur after cessation or reduction of heavy and prolonged alcohol use; manifestations are characterized by autonomic hyperactivity and central nervous system excitation 1, 2 • Severe symptom manifestations (eg, seizures, delirium tremens) may develop in up to 5% of patients 3 CLASSIFICATION • Based on severity ○ Minor alcohol withdrawal syndrome 4, 5 – Manifestations occur early, within the first 48 hours after last drink or decrease in consumption 6 □ Manifestations develop about 6 hours after last drink or decrease in consumption and usually peak about 24 to 36 hours; resolution occurs in 2 to 7 days 7 if withdrawal does not progress to major alcohol withdrawal syndrome 4 – Characterized by mild autonomic hyperactivity (eg, tachycardia, hypertension, diaphoresis, hyperreflexia), mild tremor, anxiety, irritability, sleep disturbances (eg, insomnia, vivid dreams), gastrointestinal symptoms (eg, anorexia, nausea, vomiting), headache, and craving alcohol 4 ○ Major alcohol withdrawal syndrome 5, 4 – Progression and worsening of withdrawal manifestations, usually after about 24 hours from the onset of initial manifestations 4 □ Manifestations often peak around 50 hours before gradual resolution or may continue to progress to severe (complicated) withdrawal, particularly without treatment 4 – Characterized by moderate to severe autonomic hyperactivity (eg, tachycardia, hypertension, diaphoresis, hyperreflexia, fever); marked tremor; pronounced anxiety, insomnia, -

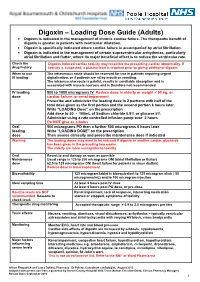

Digoxin – Loading Dose Guide (Adults) Digoxin Is Indicated in the Management of Chronic Cardiac Failure

Digoxin – Loading Dose Guide (Adults) Digoxin is indicated in the management of chronic cardiac failure. The therapeutic benefit of digoxin is greater in patients with ventricular dilatation. Digoxin is specifically indicated where cardiac failure is accompanied by atrial fibrillation. Digoxin is indicated in the management of certain supraventricular arrhythmias, particularly atrial fibrillation and flutter, where its major beneficial effect is to reduce the ventricular rate. Check the Digoxin-induced cardiac toxicity may resemble the presenting cardiac abnormality. If drug history toxicity is suspected, a plasma level is required prior to giving additional digoxin. When to use The intravenous route should be reserved for use in patients requiring urgent IV loading digitalisation, or if patients are nil by mouth or vomiting. The intramuscular route is painful, results in unreliable absorption and is associated with muscle necrosis and is therefore not recommended. IV loading 500 to 1000 micrograms IV Reduce dose in elderly or weight < 50 kg, or dose cardiac failure, or renal impairment Prescribe and administer the loading dose in 2 portions with half of the total dose given as the first portion and the second portion 6 hours later. Write “LOADING Dose” on the prescription Add dose to 50 - 100mL of Sodium chloride 0.9% or glucose 5% Administer using a rate controlled infusion pump over 2 hours Do NOT give as a bolus Oral 500 micrograms PO then a further 500 micrograms 6 hours later loading Write “LOADING DOSE” on the prescription dose Then assess clinically and prescribe maintenance dose if indicated Warning The loading doses may need to be reduced if digoxin or another cardiac glycoside has been given in the preceding two weeks. -

Two Compartment Body Model and Vd Terms by Jeff Stark

Two Compartment Body Model and Vd Terms by Jeff Stark In a one-compartment model, we make two important assumptions: (1) Linear pharmacokinetics - By this, we mean that elimination is first order and that pharmacokinetic parameters (ke, Vd, Cl) are not affected by the amount of the dose. Of course, a change in dose will be reflected by a proportional change in plasma concentration. (2) Immediate distribution and equilibrium of the drug throughout the body. Considering these assumptions, we can easily describe the Cp vs t profile of a drug after an iv bolus injection (the same principles apply to other routes of administration as well) by the exponential equation: − Cp(t) = Ce• kte p0 Dose − = • e kte Vd ln Cp m=-ke t Since immediate distribution is assumed, the whole body is treated as one unit. The slope of the graph represents the total elimination constant of the drug out of the body regardless of the elimination pathway: ke = kren + kmet + kbil + .…. This one compartment model can often be used to predict Cp vs t profile and other pharmacokinetic parameters. The truth is, however, that very few drugs show immediate distribution and equilibrium through the body. If distribution is minimal, the one compartment can be an adequate approximation. (We want to use the simplest model we can). If not, we must alter the model to better fit the data. The "next step up" is the Two-Compartment body Model which includes a peripheral compartment into which the drug may distribute. Multicompartmental/Two Compartment Body Model 1 THE TWO COMPARTMENT MODEL i.v. -

Pharmacology Part 2: Introduction to Pharmacokinetics

J of Nuclear Medicine Technology, first published online May 3, 2018 as doi:10.2967/jnmt.117.199638 PHARMACOLOGY PART 2: INTRODUCTION TO PHARMACOKINETICS. Geoffrey M Currie Faculty of Science, Charles Sturt University, Wagga Wagga, Australia. Regis University, Boston, USA. Correspondence: Geoff Currie Faculty of Science Locked Bag 588 Charles Sturt University Wagga Wagga 2678 Australia Telephone: 02 69332822 Facsimile: 02 69332588 Email: [email protected] Foot line: Introduction to Pharmacokinetics 1 Abstract Pharmacology principles provide key understanding that underpins the clinical and research roles of nuclear medicine practitioners. This article is the second in a series of articles that aims to enhance the understanding of pharmacological principles relevant to nuclear medicine. This article will build on the introductory concepts, terminology and principles of pharmacodynamics explored in the first article in the series. Specifically, this article will focus on the basic principles associated with pharmacokinetics. Article 3 will outline pharmacology relevant to pharmaceutical interventions and adjunctive medications employed in general nuclear medicine, the fourth pharmacology relevant to pharmaceutical interventions and adjunctive medications employed in nuclear cardiology, the fifth the pharmacology related to contrast media associated with computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and the final article will address drugs in the emergency trolley. 2 Introduction As previously outlined (1), pharmacology is the scientific study of the action and effects of drugs on living systems and the interaction of drugs with living systems (1-7). For general purposes, pharmacology is divided into pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics (Figure 1). The principle of pharmacokinetics is captured by philosophy of Paracelsus (medieval alchemist); “only the dose makes a thing not a poison” (1,8,9). -

Mechanism of Action Pharmacokinetics

NDA 21-748/S-002 Page 3 Glumetza ™, 500 mg (metformin hydrochloride extended release tablets) tablet, film coated, extended release DESCRIPTION GLUMETZA (metformin hydrochloride) extended release tablet is an oral antihyperglycemic drug used in the management of type 2 diabetes. Metformin hydrochloride (N,N- dimethylimidodicarbonimidic diamide hydrochloride) is not chemically or pharmacologically related to any other classes of oral antihyperglycemic agents. The structural formula of metformin hydrochloride (metformin HCl) is as shown: Metformin HCl is a white to off-white crystalline compound with a molecular formula of C4H11N5•HCl and a molecular weight of 165.63. Metformin HCl is freely soluble in water and is practically insoluble in acetone, ether, and chloroform. The pKa of metformin is 12.4. The pH of a 1% aqueous solution of metformin hydrochloride is 6.68. GLUMETZA tablets are modified release dosage forms that contain 500 mg or 1000 mg of metformin HCl. Each 500 mg tablet contains coloring, hypromellose, magnesium stearate, microcrystalline cellulose and polyethylene oxide. Each 1000 mg tablet contains crospovidone, dibutyl sebacate, ethylcellulose, glyceryl behenate, polyvinyl alcohol, polyvinylpyrrolidone, and silicon dioxide. GLUMETZA 500 and 1000 mg tablets both utilize polymer- based, oral drug delivery systems, which allow delivery of metformin HCl to the upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract. CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY Mechanism of Action Metformin is an antihyperglycemic agent, which improves glucose tolerance in patients with type 2 diabetes, lowering both basal and postprandial plasma glucose. Its pharmacologic mechanisms of action are different from other classes of oral antihyperglycemic agents. Metformin decreases hepatic glucose production, decreases intestinal absorption of glucose, and improves insulin sensitivity by increasing peripheral glucose uptake and utilization. -

Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacology of Drugs Used in Children

Drug and Fluid Th erapy SECTION II Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacology of Drugs Used CHAPTER 6 in Children Charles J. Coté, Jerrold Lerman, Robert M. Ward, Ralph A. Lugo, and Nishan Goudsouzian Drug Distribution Propofol Protein Binding Ketamine Body Composition Etomidate Metabolism and Excretion Muscle Relaxants Hepatic Blood Flow Succinylcholine Renal Excretion Intermediate-Acting Nondepolarizing Relaxants Pharmacokinetic Principles and Calculations Atracurium First-Order Kinetics Cisatracurium Half-Life Vecuronium First-Order Single-Compartment Kinetics Rocuronium First-Order Multiple-Compartment Kinetics Clinical Implications When Using Short- and Zero-Order Kinetics Intermediate-Acting Relaxants Apparent Volume of Distribution Long-Acting Nondepolarizing Relaxants Repetitive Dosing and Drug Accumulation Pancuronium Steady State Antagonism of Muscle Relaxants Loading Dose General Principles Central Nervous System Effects Suggamadex The Drug Approval Process, the Package Insert, and Relaxants in Special Situations Drug Labeling Opioids Inhalation Anesthetic Agents Morphine Physicochemical Properties Meperidine Pharmacokinetics of Inhaled Anesthetics Hydromorphone Pharmacodynamics of Inhaled Anesthetics Oxycodone Clinical Effects Methadone Nitrous Oxide Fentanyl Environmental Impact Alfentanil Oxygen Sufentanil Intravenous Anesthetic Agents Remifentanil Barbiturates Butorphanol and Nalbuphine 89 A Practice of Anesthesia for Infants and Children Codeine Antiemetics Tramadol Metoclopramide Nonsteroidal Anti-infl ammatory Agents 5-Hydroxytryptamine -

Review of Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacogenetics in Atypical Long-Acting Injectable Antipsychotics

pharmaceutics Review Review of Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacogenetics in Atypical Long-Acting Injectable Antipsychotics Francisco José Toja-Camba 1,2,† , Nerea Gesto-Antelo 3,†, Olalla Maroñas 3,†, Eduardo Echarri Arrieta 4, Irene Zarra-Ferro 2,4, Miguel González-Barcia 2,4 , Enrique Bandín-Vilar 2,4 , Victor Mangas Sanjuan 2,5,6 , Fernando Facal 7,8 , Manuel Arrojo Romero 7, Angel Carracedo 3,9,10,* , Cristina Mondelo-García 2,4,* and Anxo Fernández-Ferreiro 2,4,* 1 Pharmacy Department, University Clinical Hospital of Ourense (SERGAS), Ramón Puga 52, 32005 Ourense, Spain; [email protected] 2 Clinical Pharmacology Group, Institute of Health Research (IDIS), Travesía da Choupana s/n, 15706 Santiago de Compostela, Spain; [email protected] (I.Z.-F.); [email protected] (M.G.-B.); [email protected] (E.B.-V.); [email protected] (V.M.S.) 3 Genomic Medicine Group, CIMUS, University of Santiago de Compostela, 15782 Santiago de Compostela, Spain; [email protected] (N.G.-A.); [email protected] (O.M.) 4 Pharmacy Department, University Clinical Hospital of Santiago de Compostela (SERGAS), Citation: Toja-Camba, F.J.; 15706 Santiago de Compostela, Spain; [email protected] Gesto-Antelo, N.; Maroñas, O.; 5 Department of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Technology and Parasitology, University of Valencia, Echarri Arrieta, E.; Zarra-Ferro, I.; 46100 Valencia, Spain González-Barcia, M.; Bandín-Vilar, E.; 6 Interuniversity Research Institute for Molecular Recognition and Technological Development,