Life at the Bottom of Babylonian Society Culture and History of the Ancient Near East

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Downloadable (Ur 2014A)

oi.uchicago.edu i FROM SHERDS TO LANDSCAPES oi.uchicago.edu ii oi.uchicago.edu iii FROM SHERDS TO LANDSCAPES: STUDIES ON THE ANCIENT NEAR EAST IN HONOR OF McGUIRE GIBSON edited by MARK ALTAWEEL and CARRIE HRITZ with contributions by ABBAS ALIZADEH, BURHAN ABD ALRATHA ALRATHI, MARK ALTAWEEL, JAMES A. ARMSTRONG, ROBERT D. BIGGS, MIGUEL CIVIL†, JEAN M. EVANS, HUSSEIN ALI HAMZA, CARRIE HRITZ, ERICA C. D. HUNTER, MURTHADI HASHIM JAFAR, JAAFAR JOTHERI, SUHAM JUWAD KATHEM, LAMYA KHALIDI, KRISTA LEWIS, CARLOTTA MAHER†, AUGUSTA MCMAHON, JOHN C. SANDERS, JASON UR, T. J. WILKINSON†, KAREN L. WILSON, RICHARD L. ZETTLER, and PAUL C. ZIMMERMAN STUDIES IN ANCIENT ORIENTAL CIVILIZATION • VOLUME 71 THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO CHICAGO • ILLINOIS oi.uchicago.edu iv ISBN (paperback): 978-1-61491-063-3 ISBN (eBook): 978-1-61491-064-0 Library of Congress Control Number: 2021936579 ISSN: 0081-7554 The Oriental Institute, Chicago © 2021 by the University of Chicago. All rights reserved. Published 2021. Printed in the United States of America Series Editors Charissa Johnson, Steven Townshend, Leslie Schramer, and Thomas G. Urban with the assistance of Rebecca Cain and Emily Smith and the production assistance of Jalissa A. Barnslater-Hauck and Le’Priya White Cover Illustration Drawing: McGuire Gibson, Üçtepe, 1978, by Peggy Sanders Design by Steven Townshend Leaflet Drawings by Peggy Sanders Printed by ENPOINTE, Brooklyn Park, Minnesota, USA This paper meets the requirements of ANSI Z39.48-1984 (Permanence of Paper) ∞ oi.uchicago.edu v TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Abbreviations ................................................................................. vii Editor’s Note ........................................................................................ ix Introduction. Richard L. -

Osman Hamdi Bey and the Americans: Archaeology, Diplomacy, Art

Annika K. Johnson exhibition review of Osman Hamdi Bey and the Americans: Archaeology, Diplomacy, Art Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 11, no. 3 (Autumn 2012) Citation: Annika K. Johnson, exhibition review of “Osman Hamdi Bey and the Americans: Archaeology, Diplomacy, Art,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 11, no. 3 (Autumn 2012), http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/autumn12/johnson-reviews-osman-hamdi-bey-and-the- americans. Published by: Association of Historians of Nineteenth-Century Art. Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. Johnson: Osman Hamdi Bey and the Americans: Archaeology, Diplomacy, Art Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 11, no. 3 (Autumn 2012) Osman Hamdi Bey and the Americans: Archaeology, Diplomacy, Art The Suna and Inan Kıraç Foundation Pera Museum, Istanbul October 14, 2011 – January 8, 2012 Archaeologists and Travelers in Ottoman Lands University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia September 26, 2010 – June 26, 2011 Catalogue: Osman Hamdi Bey and the Americans: Archaeology, Diplomacy, Art (Osman Hamdi Bey & Amerikalilar: Arkeoloji, Diplomas, Sanat) Edited by Renata Holod and Robert Ousterhout, with essays by Renata Holod, Robert Ousterhout, Susan Heuck Allen, Bonna D. Wescoat, Richard L. Zettler, Jamie Sanecki, Heather Hughes, Emily Neumeier, and Emine Fetvaci. Istanbul: Pera Museum Publication, 2011. 411 pp.; 96 b/w; 119 color; bibliography 90TL (Turkish Lira) ISBN 978-975-9123-89-5 The quietly monumental exhibition, titled Osman Hamdi Bey and the Americans: Archaeology, Diplomacy, Art, was the product of a surprising collaboration between the Suna and Inan Kıraç Foundation Pera Museum in Istanbul and the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology in Philadelphia. -

Nippur, Iraq Expedition Records 1017 Finding Aid Prepared by L

Nippur, Iraq expedition records 1017 Finding aid prepared by L. Daly, K. Moreau, M. E. Ruwell, & M. Fredricks. Last updated on March 02, 2017. University of Pennsylvania, Penn Museum Archives Nippur, Iraq expedition records Table of Contents Summary Information....................................................................................................................................3 Biography/History..........................................................................................................................................4 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 5 Administrative Information........................................................................................................................... 5 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................5 Collection Inventory...................................................................................................................................... 7 Haynes Collection [Including Wolfe Expedition, 1884-85]................................................................... 7 Expeditions I & II................................................................................................................................... 8 Expedition III.........................................................................................................................................12 -

Nippur; Or, Explorations and Adventures on the Euphrates; The

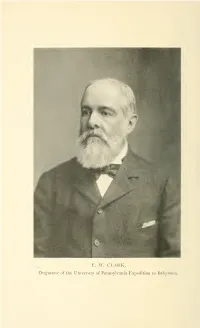

E. \V. CLARK. Originator of the University of Pennsylvania Expedition to Babylonia. NIPPUR OR EXPLORATIONS AND ADVENTURES ON THE EUPHRATES THE NARRATIVE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA EXPEDITION TO BABYLONIA IN THE YEARS 1888-1890 BY JOHN PUNNETT PETERS, PH.D., Sc.D., D.D. Director of the Expedition WITH ILLUSTRATIONS AND MAPS VOLUME 1. FIRST CAMPAIGN SECOND EDITION G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS NEW YORK AND LONDON i,\t llnickcrbocktt ^rcss i8q8 Copyright, 1897 BY G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS Entered at Stationers' Hall, London Ube Iktiicherbocfter iPress, IRew jgorft To THE Public-Spirited Gentlemen OF Philadelphia WHO MADE THE EXPEDITION POSSIBLE THESE Volumes are Respectfully Dedicated PREFACE. No city in this country has shown an interest in archeol- ogy at all comparable with that displayed by Philadelphia, A group of public-spirited gentlemen in that city has given without stint time and money for explorations in Babylonia, Egypt, Central America, Italy, Greece, and our own land ; and has, within the last ten years amassed archaeological col- lections which are unsurpassed in this country. The first im- portant work undertaken was the Babylonian Expedition. As described in the Narrative, this expedition was inaugurated by a Philadelphia banker, Mr. E. W. Clark. The enterprise was taken up in its infancy by the University of Pennsylvania, under the lead of its provost, Dr. William Pepper. Dr. Pepper made this expedition and the little band of men who liad become interested in it the nucleus for further enterprises. A library and museum were built, an Archaeological Associa- tion was formed, and a band of men was gathered together in Philadelphia who have contributed with a liberality and en- thusiasm quite unparalleled for the prosecution of archaeologi- cal research in almost all parts of the world. -

Eugenics Is Euphemism”

Blackburn 1 “Eugenics is Euphemism”: The American Eugenics Movement, the Cultural Law of Progress, and Its International Connections & Consequences1 By: Bess Blackburn 1 G.K. Chesterton, Eugenics and Other Evils: An Argument Against the Scientifically Organized Society, With Additional Articles by His Eugenic and Birth Control Opponents, ed. Michael W. Perry (Seattle, Washington: Inkling Books, 2000), 19. Chesterton’s original monograph was published in 1922. “Eugenics is Euphemism” is a play on words introduced by G.K. Chesterton. Not only is it a great summation of the movement but is also a play on words in Greek. See the original here (italics added): εὐγενής ευφημισμός είναι Blackburn 2 “EUGENICS IS EUPHEMISM”: THE AMERICAN EUGENICS MOVEMENT, THE CULTURAL LAW OF PROGRESS, AND ITS INTERNATIONAL CONNECTIONS AND CONSEQUENCES By: Bess Blackburn Liberty University APPROVED BY: David L. Snead, Ph.D., Committee Chair Christopher J. Smith, Ph.D., Committee Member Blackburn 3 Acknowledgements Hope that looks hopeful is no hope at all For what does one gain if he knows he won’t fall? It’s always darkest before the dawn Silence deafens before every magnificent song. Gratitude is an understatement for the way I feel upon completion of this, my first sizable work. While it is a work investigating a dark movement and moment in history, this project has brought me hope that we may yet rid ourselves of any trace of eugenical mindsets and look longingly towards the idea that all are created in the image of God Himself. To those who have invested in me, including Dr. Jennifer Bryson, Dr. -

Yale Historical Review an Undergraduate Publication Spring 2017

THE YALE HISTORICAL REVIEW AN UNDERGRADUATE PUBLICATION SPRING 2017 THE YALE HISTORICAL REVIEW AN UNDERGRADUATE PUBLICATION The Yale Historical Review provides undergraduates an opportunity to have their exceptional work highlighted and SPRING 2017 ISSUE encourages the diffusion of original historical ideas on college VOLUME VI campuses by providing a forum for outstanding undergraduate ISSUE II papers covering any historical topic. The Yale Historical Review Editorial Board Yale gratefully acknowledges the following donors: Jacob Wasserman Greg Weiss FOUNDING PATRONS Annie Yi Association of Yale Alumni Weili Cheng For past issues and information regarding submissions, Department of History, Yale University advertisements, subscriptions, and contributions please Matthew and Laura Dominski visit our website: Jeremy Kinney and Holly Arnold Kinney In Memory of David J. Magoon HISTORICALREVIEW.YALE.EDU Sareet Majumdar Brenda and David Oestreich Or visit our Facebook page: The Program in Judaic Studies, Yale University WWW.FACEBOOK.COM/ South Asian Studies Council, YALEHISTORICALREVIEW Yale University Stauer With further questions or to provide Undergraduate Organizations Committee feedback, please e-mail us at: Derek Wang Yale Club of the Treasure Coast [email protected] Yale European Studies Council Zixiang Zhao Or write to us at: FOUNDING CONTRIBUTORS Council on Latin American and Iberian THE YALE HISTORICAL REVIEW Studies at Yale 206 ELM STREET, #205145 Peter Dominski YALE UNIVERSITY J.S. Renkert NEW HAVEN, CT 06520 Joe and Marlene -

Guaranteed Genuine Originals: the Plimpton Collection and the Early

Guaranteed Genuine Originals: The Plimpton Collection and the Early History of Mathematical Assyriology Eleanor Robson — Oxford* Prologue It may seem odd to offer Christopher Walker a paper with no British Museum tablets in it — but how else is one to surprise him? Among Christopher’s greatest contributions to the field are the very many texts he has not published himself but generously given to others to work on, myself included (Robson 1997; 1999). So in order to avoid presenting him with something he knows already, I discuss two other subjects close to his heart. By tracing the formation of the small collection which contains Plimpton 322, the most famous mathe- matical cuneiform tablet in the world (alas not in the British Museum but now held by Columbia University, New York), I aim not only to explore how the collection came to be, but also to examine attitudes to private collecting amongst early-twentieth century muse- um professionals, and to reveal a little of the impact the first publication of mathematical cuneiform tablets made on the field of history of mathematics before the First World War. The article ends with an appendix listing the cuneiform tablets in Plimpton’s collection, with copies of all his previously unpublished mathematical and school tablets. Plimpton 322 has undoubtedly been the most debated and most celebrated pre- Classical mathematical artefact of the last fifty years. First published by Neugebauer and Sachs (1945: text A), this Old Babylonian cuneiform tablet shows incontrovertibly that the relationship between the sides of right triangles was systematically known in southern Mesopotamia over a millennium before Pythagoras was supposed to have proved the * It is a particular pleasure to thank Jane Rodgers Siegel and her colleagues at the Rare Book and Manuscript Library of Columbia University, for generous and fruitful help during my visits in July 1999 and April 2000, and by email at other times. -

Tanakh, New Testament, and Qurʾan As Literature and Culture Biblical Interpretation Series

Sacred Tropes: Tanakh, New Testament, and Qurʾan as Literature and Culture Biblical Interpretation Series Editors R. Alan Culpepper Ellen van Wolde Associate Editors David E. Orton Rolf Rendtorff Editorial Advisory Board Janice Capel Anderson – Phyllis A. Bird Erhard Blum – Werner H. Kelber Ekkehard W. Stegemann – Vincent L. Wimbush Jean Zumstein VOLUME 98 Sacred Tropes: Tanakh, New Testament, and Qurʾan as Literature and Culture Edited by Roberta Sterman Sabbath LEIDEN • BOSTON 2009 This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Sacred tropes : Tanakh, New Testament, and Qurʾan as literature and culture / edited by Roberta Sterman Sabbath. p. cm. — (Biblical interpretation series, ISSN 0928-0731 ; v. 98) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-17752-9 (hardback : alk. paper) 1. Sacred books—History and criticism. 2. Judaism—Sacred books. 3. Christianity— Sacred books. 4. Islam—Sacred books. 5. Bible—Criticism, interpretation, etc. 6. Koran—Criticism, interpretation, etc. I. Sabbath, Roberta Sterman. BL71.S225 2009 208’.2—dc22 2009022350 ISSN 0928-0731 ISBN 978 90 04 17752 9 Copyright 2009 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Koninklijke Brill NV provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. -

Oxford Dictionary of Medical Quotations This Page Intentionally Left Blank Oxford Medical Publications Oxford Dictionary of Medical Quotations

Oxford Dictionary of Medical Quotations This page intentionally left blank Oxford Medical Publications Oxford Dictionary of Medical Quotations Peter McDonald 1 1 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX2 6DP Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Bangkok Buenos Aires Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kolkata Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi São Paulo Shanghai Taipei Tokyo Toronto Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York © Selection and arrangement Oxford University Press 2004 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2004 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer A catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library ISBN 0 19 263047 4 (Hbk) 1098765432 1 Typeset by Newgen Imaging Systems (P) Ltd., Chennai, India Printed in Great Britain on acid-free paper by T.J. -

Complete Text In

Nippur (Sumerian: Nibru, often logographically recorded as , EN.LÍLKI, "Enlil City;"[1] Akkadian: Nibbur) was one of the most ancient of all the Sumerian cities.[citation needed] It was the special seat of the worship of the Sumerian god Enlil, the "Lord Wind," ruler of the cosmos subject to An alone. Nippur was located in modern Nuffar in Afak, Al-Qādisiyyah Governorate, Iraq. History Nippur never enjoyed political hegemony in its own right, but its control was crucial, as it was considered capable of conferring the overall "kingship" on monarchs from other city-states. It was distinctively a sacred city, important from the possession of the famous shrine of Enlil. According to the Tummal Chronicle, Enmebaragesi, an early ruler of Kish, was the first to build up this temple. [2] His influence over Nippur has also been detected archaeologically. The Chronicle lists successive early Sumerian rulers who kept up intermittent ceremonies at the temple: Aga of Kish, son of Enmebaragesi; Mesannepada of Ur; his son Meskiang-nunna; Gilgamesh of Uruk; his son Ur-Nungal; Nanni of Ur and his son Meskiang-nanna. It also indicates that the practice was revived inNeo-Sumerian times by Ur-Nammu of Ur, and continued until Ibbi-Sin appointed Enmegalana high priest in Uruk (ca. 1950 BC). Inscriptions of Lugal-Zage-Si and Lugal-kigub-nidudu, kings of Uruk and Ur respectively, and of other early pre-Semitic rulers, on door-sockets and stone vases, show the veneration in which the ancient shrine was then held, and the importance attached to its possession, as giving a certain stamp of legitimacy. -

Peters of New England

Peters of New England A Genealogy, and Family History Compiled by Edmond Frank .:P. eters and Eleanor Bradley .Peters (Mrs. Edward McClure Peters) Author of'' Hugh Pe:ter 1 A ~1os.aic,, '!Rew ]Vorh Ube '!Rntclterbocher )Press 1903 TO THE MEMORY OF EDMOND PRANK PETERS AND OF THOMAS McCLURE PETERS, S.T.D. CONTENTS PAGE LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS AND SIGNATURES 111 THE MAKING OF THE BOOK Vl TRADITION ix INFERENCE xv CORRECTIONS AND ADDITIONS xvii EXPLANATION xxi GENEALOGY MASSACHUSETTS: IPSWICH AND ANDOVER I READING AND WAKEFIELD 53 THE REVD. ANDREW OF MIDDLETON 56 MEDFIELD 63 ANDOVER 102 MAINE: BLUE HILL II2 ELLSWORTH . 127 BOSTON 137 CONNECTICUT: HEBRON 152 COLONEL JOHN OF THE QUEEN'S LOYAL RANGERS. 186 GENERAL ABSALOM 241 THE REVEREND SAMUEL 257 NEw YoRK STATE 267 LITCHFIELD • 282 LOST TRIBES 304 Omo 31 r NEW HAMPSHIRE: SEBORNE 314 ANDREW 349 11 Contents APPENDIX: BEAMSLEY. 357 MY NATIVE LAND, Gooo-NIGHT! 361 AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF COLONEL Jmrn OF THE QUEEN'S LOYAL RANGERS 366 PETERS TRAITS , 387 DIVERS FAMILIES 394 MILITARY SERVICE 408 ALLIED FAMILIES 4r2 GENERAL INDEX • 420 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS AND SIGNATURES PAGE TITLE-PAGE, EDMOND FRANK PETERS (ABOUT 1874), SIGNATURE 1893 (see page 203) GRAVESTONE OF ANDREW PETERS, 1713 (r901) 27 WILL OF ANDREW PEETERS, 1702 28 GRAVESTONE OF' PHEBE PETERS, 1702 . 41 SITE OF HousE OF ANDREW PEETERS (1901) 43 COMMON AND PoND ADJOINING HousE OF ANDREW PEETERS (1902) 43 SIGNATURE OF SAMUEL PEETERS, 1703 . 43 GRAVE OF THE REVD. ANDREW PETERS OF MIDDLETON, 1756 (1901) 61 SIGNATURE OF JOSEPH PETERS (43) 1 1781 63 SIGNATURE OF CAPT. -

John Punnett Peters

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES JOHN PUNNETT P ETERS 1887—1955 A Biographical Memoir by J O H N RO D M A N P A U L , C Y R I L NO R M A N HU G H L ONG Any opinions expressed in this memoir are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Academy of Sciences. Biographical Memoir COPYRIGHT 1958 NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES WASHINGTON D.C. JOHN PUNNETT PETERS December 4,1887—December 29,1955 BY JOHN RODMAN PAUL AND CYRIL NORMAN HUGH LONG OHN PUNNETT PETERS * was born in Philadelphia on December 4, J 1887, the son of the Reverend John P. Peters, D.D., former rector of St. Michael's Protestant Episcopal Church in New York City, and of Gabriella Brooke Forman. As a baby he was taken to the Near East where his father, having developed special archaeolog- ical interests, went under the auspices of the Archaeological Museum of the University of Pennsylvania. This expedition was described later in an account entitled: Nippur: or Explorations and Adven- tures on the Euphrates. The discoveries resulting from the expedi- tion led to a spirited discussion which focused upon the interpreta- tion of the archaeological data and was to become known as the "Peters Controversy." Thus, the young Jack Peters was brought up in an atmosphere of crusade, particularly as his father, having relin- quished his association with the Museum on his return to this coun- try, had found time among other duties to devote his energies to a series of vigorous campaigns to reform municipal affairs in New York City.