Essays: Archaeologists and Missionaries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Foundation Figurines

Imagen aérea de uno de los Aerial view of one of the ziggu- zigurats de Babilonia. Imagen rats of Babylon. From Arqueo- de Arqueología de las ciudades logía de las ciudades perdidas, perdidas, núm. 4, 1992. Gentileza nº 4, 1992. Courtesy of Editorial de Editorial Salvat, S.L. Salvat, S. L. Tejidos mesopotámicos de 4.000 años de antigüedad: El caso de las figuritas de fundación Mesopotamian fabrics of 4000 years ago: the foundation figurines por / by Agnès Garcia-Ventura TODO EL MUNDO CONOCE EL CUENTO DE HANS CHRISTIAN ANDER- EVERYONE KNOWS HANS CHRISTIAN ANDERSEn’S TALE ABOUT THE SEN ACERCA DE LOS DOS SASTRES QUE PROMETEN AL EMPERADOR TWO TAILORS WHO PROMISE THE EMPEROR A NEW SUIT OF CLOTHES UN MÁGICO TRAJE NUEVO QUE SERÁ INVISIBLE PARA LOS IGNORAN- THAT ONLY THE WISEST AND CLEVEREST CAN SEE. WHEN THE EMPER- TES Y LOS INCOMPETENTES. CUANDO, POR FIN, EL EMPERADOR SE OR PARADES BEFORE HIS SUBJECTS IN HIS NEW CLOTHES, A CHILD PASEA ANTE SUS SÚBDITOS CON EL SUPUESTO TRAJE NUEVO, UN NIÑO CRIES OUT, “BUT HE ISn’T WEARING ANYTHING AT all!” GRITA: «¡PeRO SI NO LLEVA NINGÚN TRAJE!». A menudo, lo que aquí es simplemente una fábula sucede In the study of ancient textiles, I often think we act like the en realidad a quienes nos dedicamos al estudio de tejidos child in the fable, shouting out the obvious. But in this case antiguos. De algún modo, actuamos como el niño de la fá- it’s the other way round: “He is wearing something! Look at bula vociferando algo obvio, aunque en nuestro caso sería the textiles!” lo contrario que en el cuento de Andersen: «¡Pero si lleva To illustrate the point, in this article I will focus on two algo! ¡Mirad qué tejidos!». -

Downloadable (Ur 2014A)

oi.uchicago.edu i FROM SHERDS TO LANDSCAPES oi.uchicago.edu ii oi.uchicago.edu iii FROM SHERDS TO LANDSCAPES: STUDIES ON THE ANCIENT NEAR EAST IN HONOR OF McGUIRE GIBSON edited by MARK ALTAWEEL and CARRIE HRITZ with contributions by ABBAS ALIZADEH, BURHAN ABD ALRATHA ALRATHI, MARK ALTAWEEL, JAMES A. ARMSTRONG, ROBERT D. BIGGS, MIGUEL CIVIL†, JEAN M. EVANS, HUSSEIN ALI HAMZA, CARRIE HRITZ, ERICA C. D. HUNTER, MURTHADI HASHIM JAFAR, JAAFAR JOTHERI, SUHAM JUWAD KATHEM, LAMYA KHALIDI, KRISTA LEWIS, CARLOTTA MAHER†, AUGUSTA MCMAHON, JOHN C. SANDERS, JASON UR, T. J. WILKINSON†, KAREN L. WILSON, RICHARD L. ZETTLER, and PAUL C. ZIMMERMAN STUDIES IN ANCIENT ORIENTAL CIVILIZATION • VOLUME 71 THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO CHICAGO • ILLINOIS oi.uchicago.edu iv ISBN (paperback): 978-1-61491-063-3 ISBN (eBook): 978-1-61491-064-0 Library of Congress Control Number: 2021936579 ISSN: 0081-7554 The Oriental Institute, Chicago © 2021 by the University of Chicago. All rights reserved. Published 2021. Printed in the United States of America Series Editors Charissa Johnson, Steven Townshend, Leslie Schramer, and Thomas G. Urban with the assistance of Rebecca Cain and Emily Smith and the production assistance of Jalissa A. Barnslater-Hauck and Le’Priya White Cover Illustration Drawing: McGuire Gibson, Üçtepe, 1978, by Peggy Sanders Design by Steven Townshend Leaflet Drawings by Peggy Sanders Printed by ENPOINTE, Brooklyn Park, Minnesota, USA This paper meets the requirements of ANSI Z39.48-1984 (Permanence of Paper) ∞ oi.uchicago.edu v TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Abbreviations ................................................................................. vii Editor’s Note ........................................................................................ ix Introduction. Richard L. -

ASOR Annual Meeting Academic Program—Wednesday - Thursday

ASOR Annual Meeting Academic Program—Wednesday - Thursday Start times for each paper are listed. Please note that 5 minutes of discussion time has been allotted after the stated length of each paper. 9:50am Asa Eger (University of North Carolina- Wednesday, NOVEMBER 17th Greensboro), “Divergent Umayyad and Abbasid Period Settlement Patterns on the A1 Salon D and E Islamic-Byzantine Frontier” (35 min.) 7:00-8:30pm A3 Salon B 7:00pm Morag Kersel (DePaul University) and 8:20-10:25am Michael Homan (Xavier University of Archaeology of Anatolia I: Current Work Louisiana), Presiding Theme: Papers will offer recent discoveries and analysis of data Welcome to the Annual Meeting (5 min.) for ongoing projects across Anatolia. Sharon R. Steadman 7:05pm Timothy P. Harrison (SUNY Cortland), Presiding (University of Toronto & ASOR Pres.), 8:20am Arkadiusz Marciniak (University of Poznan), Welcome and Introductions (5 min.) “Çatalhöyük East in the Second Half of the 7:10pm Kevin Fisher (Brown University), “Making 7th Millennium cal B.C. The Minutiae of Places in Late Bonze Age Cyprus” (20 min.) Social Change” (20 min.) Plenary Address DP Kevin Cooney (Boston University), “Change 7:30pm Edgar Peltenburg (University of in Lithic Technology as an Indicator of Edinburgh), “Fashioning Identity: Cultural Transformation During the Neolithic Workshops and Cemeteries at Prehis- Period at Ulucak Höyük in Western Turkey” toric Souskiou, Cyprus” (60 min.) (15 min.) 9:10am Jason Kennedy (Binghamton University, SUNY), “Use-Alteration Analysis of Thursday, NOVEMBER 18th Terminal Ubaid Ceramics From Kenan Tepe, Diyarbakir Province, Turkey” (20 min.) A2 Salon A 9:35am Timothy Matney (University oF Akron) 8:20am-10:25am and Willis Monroe (Brown University), “Recent Archaeology of Islamic Society Excavations at Ziyaret Tepe/Tushhan: Results Theme: This is one of two sessions devoted to the archaeology from the 2009-2010 Field Seasons” (20 min.) of Islamic societies, highlighting new methods and approaches. -

A Sculpted Dish from Tello Made of a Rare Stone (Louvre–AO 153)

A Sculpted Dish from Tello Made of a Rare Stone (Louvre–AO 153) FRANÇOIS DESSET, UMR 7041 / University of Teheran* GIANNI MARCHESI, University of Bologna MASSIMO VIDALE, University of Padua JOHANNES PIGNATTI, “La Sapienza” University of Rome Introduction Close formal and stylistic comparisons with other artifacts of the same period from Tello make it clear A fragment of a sculpted stone dish from Tello (an- that Waagenophyllum limestone, stemming probably cient Ĝirsu), which was found in the early excavations from some Iranian source, was imported to Ĝirsu directed by Ernest de Sarzec, has been as studied by to be locally carved in Sumerian style in the palace us in the frame of a wider research project on artifacts workshops. Mesopotamian objects made of this rare made of a peculiar dark grey limestone spotted with stone provide another element for reconstructing white-to-pink fossil corals of the genus Waagenophyl- the patterns of material exchange between southern lum. Recorded in an old inventory of the Louvre, Mesopotamia and the Iranian Plateau in the late 3rd the piece in question has quite surprisingly remained millennium BC. unpublished until now. The special points of interest to be addressed here are: the uncommon type of stone, which was pre- The Artifact sumably obtained from some place in Iran; the finely We owe the first description of this dish fragment carved lion image that decorates the vessel; and the (Figs. 1–3), which bears the museum number AO mysterious iconographic motif that is placed on the 153, to Léon Heuzey: lion’s shoulder. A partially preserved Sumerian inscrip- tion, most probably to be attributed to the famous Une disposition semblable, mais dans des pro- ruler Gudea of Lagash should also be noted.1 portions beaucoup plus petites, se voit au pour- tour d’un élégant plateau circulaire, dont il ne * This artifact was generously brought to our attention by reste aussi qu’un fragment. -

Osman Hamdi Bey and the Americans: Archaeology, Diplomacy, Art

Annika K. Johnson exhibition review of Osman Hamdi Bey and the Americans: Archaeology, Diplomacy, Art Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 11, no. 3 (Autumn 2012) Citation: Annika K. Johnson, exhibition review of “Osman Hamdi Bey and the Americans: Archaeology, Diplomacy, Art,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 11, no. 3 (Autumn 2012), http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/autumn12/johnson-reviews-osman-hamdi-bey-and-the- americans. Published by: Association of Historians of Nineteenth-Century Art. Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. Johnson: Osman Hamdi Bey and the Americans: Archaeology, Diplomacy, Art Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 11, no. 3 (Autumn 2012) Osman Hamdi Bey and the Americans: Archaeology, Diplomacy, Art The Suna and Inan Kıraç Foundation Pera Museum, Istanbul October 14, 2011 – January 8, 2012 Archaeologists and Travelers in Ottoman Lands University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia September 26, 2010 – June 26, 2011 Catalogue: Osman Hamdi Bey and the Americans: Archaeology, Diplomacy, Art (Osman Hamdi Bey & Amerikalilar: Arkeoloji, Diplomas, Sanat) Edited by Renata Holod and Robert Ousterhout, with essays by Renata Holod, Robert Ousterhout, Susan Heuck Allen, Bonna D. Wescoat, Richard L. Zettler, Jamie Sanecki, Heather Hughes, Emily Neumeier, and Emine Fetvaci. Istanbul: Pera Museum Publication, 2011. 411 pp.; 96 b/w; 119 color; bibliography 90TL (Turkish Lira) ISBN 978-975-9123-89-5 The quietly monumental exhibition, titled Osman Hamdi Bey and the Americans: Archaeology, Diplomacy, Art, was the product of a surprising collaboration between the Suna and Inan Kıraç Foundation Pera Museum in Istanbul and the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology in Philadelphia. -

Nippur, Iraq Expedition Records 1017 Finding Aid Prepared by L

Nippur, Iraq expedition records 1017 Finding aid prepared by L. Daly, K. Moreau, M. E. Ruwell, & M. Fredricks. Last updated on March 02, 2017. University of Pennsylvania, Penn Museum Archives Nippur, Iraq expedition records Table of Contents Summary Information....................................................................................................................................3 Biography/History..........................................................................................................................................4 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 5 Administrative Information........................................................................................................................... 5 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................5 Collection Inventory...................................................................................................................................... 7 Haynes Collection [Including Wolfe Expedition, 1884-85]................................................................... 7 Expeditions I & II................................................................................................................................... 8 Expedition III.........................................................................................................................................12 -

Comptabilités, 8 | 2016 Archives and Bookkeeping in Southern Mesopotamia During the Ur III Period 2

Comptabilités Revue d'histoire des comptabilités 8 | 2016 Archéologie de la comptabilité. Culture matérielle des pratiques comptables au Proche-Orient ancien Archives and Bookkeeping in Southern Mesopotamia during the Ur III period Archéologie de la comptabilité. Culture matérielle des pratiques comptables au Proche-Orient ancien Archives et comptabilité dans le Sud mésopotamien pendant la période d’Ur III Archive und Rechnungswesen im Süden Mesopotamiens im Zeitalter von Ur III Archivos y contabilidad en el Periodo de Ur III (2110-2003 a.C.) Manuel Molina Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/comptabilites/1980 ISSN: 1775-3554 Publisher IRHiS-UMR 8529 Electronic reference Manuel Molina, « Archives and Bookkeeping in Southern Mesopotamia during the Ur III period », Comptabilités [Online], 8 | 2016, Online since 20 June 2016, connection on 19 April 2019. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/comptabilites/1980 This text was automatically generated on 19 April 2019. Tous droits réservés Archives and Bookkeeping in Southern Mesopotamia during the Ur III period 1 Archives and Bookkeeping in Southern Mesopotamia during the Ur III period* Archéologie de la comptabilité. Culture matérielle des pratiques comptables au Proche-Orient ancien Archives et comptabilité dans le Sud mésopotamien pendant la période d’Ur III Archive und Rechnungswesen im Süden Mesopotamiens im Zeitalter von Ur III Archivos y contabilidad en el Periodo de Ur III (2110-2003 a.C.) Manuel Molina 1 By the end of the 22nd century BC, king Ur-Namma inaugurated in Southern Mesopotamia the so-called Third Dynasty of Ur (2110-2003 BC). In this period, a large, well structured and organized state was built up, to such an extent that it has been considered by many a true empire. -

1889 Consular Dispatch from Baghdad Lee Ann Potter

Social Education 71(7), pp 344–347 ©2007 National Council for the Social Studies Teaching with Documents 1889 Consular Dispatch from Baghdad Lee Ann Potter In the late summer of 1888, officials at the U.S. Department of State appointed George L. Rives, the assistant secre- John Henry Haynes of Rowe, Massachusetts, to become the first U.S. consul in tary of state. In his single-page, hand- Baghdad. At that time, Baghdad—along with all of present day Iraq—was part of written message, he announced that he the Ottoman Empire, as it had been for more than three centuries. As the twentieth had safely arrived in Baghdad after century approached, U.S. diplomatic and commercial interests in the region were well having been “unavoidably delayed established and growing. There were already American consulates in the Ottoman on the overland journey by caravan capital of Constantinople, as well as in Beirut, Cairo, Jerusalem, Sivas, and Smyrna. from Alexandretta.” The message was In addition, American consular agents worked in 23 other cities within the empire. sent via Constantinople and reached Washington in late February. Establishing a consulate at Baghdad Nippur (Niffer) in southeastern Iraq. For the next three years, Haynes wrote had been discussed as early as 1885, While working for the Fund, under the nearly two dozen additional dispatches when members of the American Oriental leadership of its director, John Punnett to officials in Washington. His succes- Society formed a committee to raise Peters, Haynes would also serve as the sor, John C. Sundberg, a Norwegian- funds to send the first American archae- American consul, fostering trade rela- born doctor who became a naturalized ological expedition to Mesopotamia. -

Université De Pau Et Des Pays De L'adour

Université de P au et des Pays de l’Adour ECOLE DOCTORALE 481 SCIENCES SOCIALES ET HUMANITES Thèse de doctorat L’ART CONTEMPORAIN D U MOYEN-ORIENT ENTRE TRADITIONS ET NOUVEAUX DEFIS Présenté par Madame Susanne DRAKE Sous la direction de Madame Evelyne TOUSSAINT Membres du jury : Madame Evelyne TOUSSAINT, professeur à Aix-Marseille Université, précédemment professeur à l'U niversité de Pau et des Pays de l’Adour Monsieur Rémi LABRUSSE , Professeur d’ Université de Paris Ouest Nanterre-La Défense Monsieur Dominique DUSSOL , Professeur de l’Université de Pau et des Pays de l’Adour Monsieur Eric BONNET , Professeur de l’Université de Paris VIII Date de soutenance : 10 Juin 2014 1 Résumé fran çais et mots clefs Dans les pays du Moyen Orient, nous sommes face à une réalité complexe, qui est encore peu comprise en Europe. Les médias nous dépeignent souvent une société majoritairement islamique fondamentaliste. Cette image, qui pourrait relever d’une représentation tardive du Moyen Orient par l’Occident est empreinte de problématiques d’ordre économique et soci étal. Une analyse précise permet de mettre au jour des singularités nationales et intranationales. Les développements artistiques profitent de ces sources multiples. Pour inclure les artistes du Moyen Orient dans l’histoire de l’art du monde , et comprendre les œuvres d’art contemporain, nous nous sommes servis de plusieurs approches. O utre l’analyse esthétique et la recherche d’influences formelles, il s’agit de comprendre les positions politiques de l'artiste, sa psychologie, son rôle dans la société, mais aussi la place de la religion dans la vie publique, la valeur attribuée à l’art contemporain et sa réception dans la société. -

ROBERT G. OUSTERHOUT (Updated 05/20)

ROBERT G. OUSTERHOUT (updated 05/20) ___________________________________________ History of Art Department University of Pennsylvania 3405 Woodland Walk Philadelphia, PA 19104-6208 Home: 414 S. 47th St., Philadelphia, PA 19143 e-mail: [email protected] ___________________________________________ Research Interests: Byzantine and medieval architecture, monumental painting, sacred spaces, and urbanism in the Eastern Mediterranean: primarily in Istanbul, Cappadocia, Thrace, Greece, and Jerusalem. Education: University of Oregon, Eugene, OR (1968-70, 1972-73), B.A. (Honors College) in Art History, 1973 Institute of European Studies, Vienna, Austria (1970-72) University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH (1975-77), M.A. in Art History, 1977 University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (1977-81), Ph.D. in Art History, awarded 1982 Academic Positions: University of Oregon, Eugene, Department of Art History Assistant Professor, (Sept. 1981-Dec. 1982) University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, School of Architecture Assistant Professor of Architectural History (Jan. 1983-Aug. 1988) Associate Professor (Aug. 1988-Aug. 1993) Professor (Aug. 1993-Dec. 2006) Chair, Architectural History and Preservation (1994-1999; 2005-2006) Coordinator, Ph.D. Program in Architecture and Landscape Architecture (2002-2006) University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, Department of the History of Art Professor of Byzantine Art and Architecture (Jan. 2007- June 2017) Director, Center for Ancient Studies (2007-16) Chair, Graduate Group in the History of Art (2009-12) Chair, -

Life at the Bottom of Babylonian Society Culture and History of the Ancient Near East

Life at the Bottom of Babylonian Society Culture and History of the Ancient Near East Founding Editor M.H.E. Weippert Editor-in-Chief Thomas Schneider Editors Eckart Frahm W. Randall Garr B. Halpern Theo P.J. van den Hout Irene J. Winter VOLUME 51 The titles published in this series are listed at: www.brill.nl/chan Life at the Bottom of Babylonian Society Servile Laborers at Nippur in the 14th and 13th Centuries B.C. By Jonathan S. Tenney LEIDEN • BOSTON LEIDEN • BOSTON 2011 This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Tenney, Jonathan S. Life at the bottom of Babylonian society : servile laborers at Nippur in the 14th and 13th centuries, B.C. / by Jonathan S. Tenney. p. cm. -- (Culture and history of the ancient Near East, ISSN 1566-2055 ; v. 51) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-20689-2 (hbk. : alk. paper) 1. Working class--Iraq--Nippur (Extinct city)- -History. 2. Labor--Iraq--Nippur (Extinct city)--History. 3. Social status--Iraq--Nippur (Extinct city)--History. 4. Families--Iraq--Nippur (Extinct city)--History. 5. Nippur (Extinct city)--Population--History. 6. Nippur (Extinct city)--History--Sources. 7. Nippur (Extinct city)--Social conditions. 8. Nippur (Extinct city)--Economic conditions. 9. Babylonia--Social conditions. 10. Babylonia--Economic conditions. I. Title. HD4844.T46 2011 305.5’620935--dc22 2011011313 ISSN 1566-2055 ISBN 978-90-04-20689-2 Copyright 2011 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Global Oriental, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP. -

Nippur; Or, Explorations and Adventures on the Euphrates; The

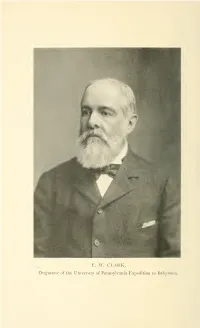

E. \V. CLARK. Originator of the University of Pennsylvania Expedition to Babylonia. NIPPUR OR EXPLORATIONS AND ADVENTURES ON THE EUPHRATES THE NARRATIVE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA EXPEDITION TO BABYLONIA IN THE YEARS 1888-1890 BY JOHN PUNNETT PETERS, PH.D., Sc.D., D.D. Director of the Expedition WITH ILLUSTRATIONS AND MAPS VOLUME 1. FIRST CAMPAIGN SECOND EDITION G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS NEW YORK AND LONDON i,\t llnickcrbocktt ^rcss i8q8 Copyright, 1897 BY G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS Entered at Stationers' Hall, London Ube Iktiicherbocfter iPress, IRew jgorft To THE Public-Spirited Gentlemen OF Philadelphia WHO MADE THE EXPEDITION POSSIBLE THESE Volumes are Respectfully Dedicated PREFACE. No city in this country has shown an interest in archeol- ogy at all comparable with that displayed by Philadelphia, A group of public-spirited gentlemen in that city has given without stint time and money for explorations in Babylonia, Egypt, Central America, Italy, Greece, and our own land ; and has, within the last ten years amassed archaeological col- lections which are unsurpassed in this country. The first im- portant work undertaken was the Babylonian Expedition. As described in the Narrative, this expedition was inaugurated by a Philadelphia banker, Mr. E. W. Clark. The enterprise was taken up in its infancy by the University of Pennsylvania, under the lead of its provost, Dr. William Pepper. Dr. Pepper made this expedition and the little band of men who liad become interested in it the nucleus for further enterprises. A library and museum were built, an Archaeological Associa- tion was formed, and a band of men was gathered together in Philadelphia who have contributed with a liberality and en- thusiasm quite unparalleled for the prosecution of archaeologi- cal research in almost all parts of the world.