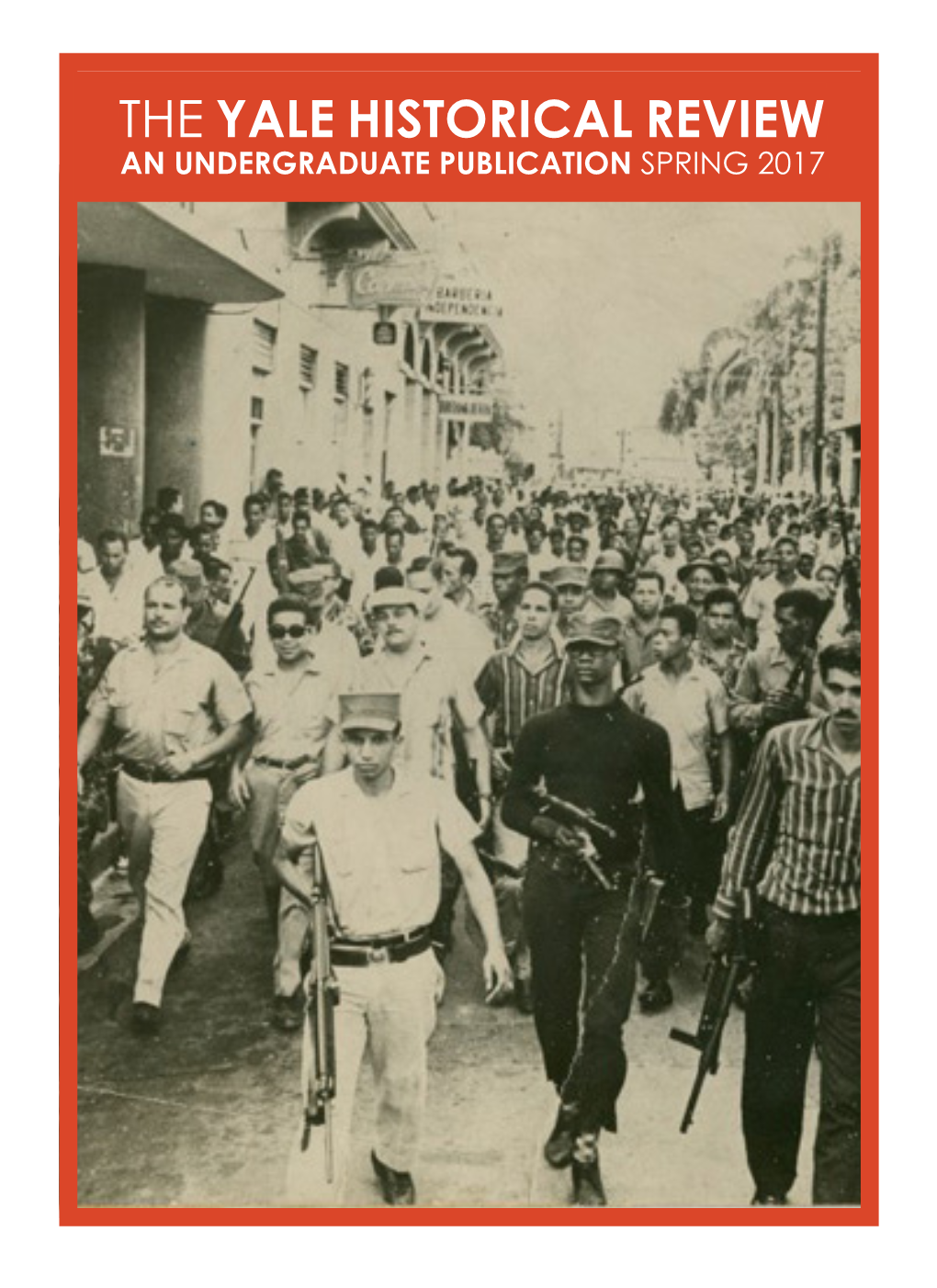

Yale Historical Review an Undergraduate Publication Spring 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Redalyc.UNA ISLA Y DOS NACIONES: LAS RELACIONES DOMÍNICO

Ciencia y Sociedad ISSN: 0378-7680 [email protected] Instituto Tecnológico de Santo Domingo República Dominicana Carrón, Hayden UNA ISLA Y DOS NACIONES: LAS RELACIONES DOMÍNICO-HAITIANAS EN EL MASACRE SE PASA A PIE DE FREDDY PRESTOL CASTILLO Ciencia y Sociedad, vol. 40, núm. 2, 2015, pp. 285-305 Instituto Tecnológico de Santo Domingo Santo Domingo, República Dominicana Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=87041161003 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto UNA ISLA Y DOS NACIONES: LAS RELACIONES DOMÍNICO-HAITIANAS EN EL MASACRE SE PASA A PIE DE FREDDY PRESTOL CASTILLO An island and two nations: The Dominican-Haitian relations in The Slaughter Walk Pass by Freddy Prestol Castillo Hayden Carrón * Resumen : La frontera entre la República Dominicana y Haití ha sido tradicionalmente un lugar difuso, mítico y también trágico. A través de ella se cuentan historias de las poblaciones de dos países muy cercanos en composición étnica, pero muy diversos en el plano cultural. Esta porosa región de la isla fue testigo de la más sangrienta matanza étnica que ha tenido lugar en el Caribe durante el siglo XX . En 1937, el dictador dominicano Rafael Trujillo ordenó el asesinato de todos los haitianos que se encontraran del lado dominicano de la frontera. Este horrendo episodio ha sido contado en numerosas ocasiones por escritores haitianos. -

See Attachment

T able of Contents Welcome Address ................................................................................4 Committees ............................................................................................5 10 reasons why you should meet in Athens....................................6 General Information ............................................................................7 Registration............................................................................................11 Abstract Submission ............................................................................12 Social Functions....................................................................................13 Preliminary Scientific Program - Session Topics ..........................14 Preliminary List of Faculty..................................................................15 Hotel Accommodation..........................................................................17 Hotels Description ................................................................................18 Optional Tours........................................................................................21 Pre & Post Congress Tours ................................................................24 Important Dates & Deadlines ............................................................26 3 W elcome Address Dear Colleagues, You are cordially invited to attend the 28th Politzer Society Meeting in Athens. This meeting promises to be one of the world’s largest gatherings of Otologists. -

Spring-2012.Pdf

AlumniGazetteWESTERn’S ALUMNI MaGAZINE SINCE 1939 SPRING 2012 AT THE PL ATE WITH BLUE JAYS PRESIDENT & CEO PAUL BEESTON Buying?Buying? Renewing?Renewing? Refinancing?Refinancing? AlumniGazette Buying?Buying?Buying?Buying? Renewing?Renewing?Renewing?Renewing? Refinancing?Refinancing?Refinancing?Refinancing? CONTENTS ‘EVERY DAY IS SATURDAY’ 10 Cover story: At the plate with Blue Jays president & CEO Paul Beeston, BA’67, LLD’94 A DIPLOMAT FINDS HER 14 CALLING Sheila Siwela, BA’79, Zambia’s ambassador to the United States THE RIVER RUNS DEEP 16 Valiya Hamza, PhD’73, discovers underground river in Brazil THE WILL TO WIN 18 Silken Laumann, BA’89, reflects on her bronze medal win at the ’92 Olympics NEVER SaY NEVER 20 Tim Hudak, BA’90, and his path to Queen's Park 22 ROCK STAR CommittedCommitted to to Saving Saving YouYou ThousandsThousands Richard Léveillé, PhD’01, and NASA’s Mars CommittedCommittedCommitted to toto Saving SavingSaving You YouYou Thousands ThousandsThousands mission ofof Dollars Dollars on on Your Your NextNext MortgageMortgage ofofof Dollars DollarsDollars on onon Your YourYour Next NextNext Mortgage MortgageMortgage THE CIRQUE LIFE Alumni of Western University can SAVE on a mortgage 26 Craig Cohon, BA’85, brings Cirque du Soleil AlumniAlumniAlumni of of ofWestern Western Western UniversityUniversity University can can SAVE SAVE on onon a aa mortgage mortgagemortgage to Russia withAlumni the of best Western available University rates in can Canada SAVE while on a enjoyingmortgage withwithwith the the the best best best available available available ratesrates rates in in Canada Canada whilewhile while enjoying enjoyingenjoying outstandingwith the best service. available Whether rates in purchasing Canada while your enjoying first 20 outstandingoutstandingoutstanding service. -

Downloadable (Ur 2014A)

oi.uchicago.edu i FROM SHERDS TO LANDSCAPES oi.uchicago.edu ii oi.uchicago.edu iii FROM SHERDS TO LANDSCAPES: STUDIES ON THE ANCIENT NEAR EAST IN HONOR OF McGUIRE GIBSON edited by MARK ALTAWEEL and CARRIE HRITZ with contributions by ABBAS ALIZADEH, BURHAN ABD ALRATHA ALRATHI, MARK ALTAWEEL, JAMES A. ARMSTRONG, ROBERT D. BIGGS, MIGUEL CIVIL†, JEAN M. EVANS, HUSSEIN ALI HAMZA, CARRIE HRITZ, ERICA C. D. HUNTER, MURTHADI HASHIM JAFAR, JAAFAR JOTHERI, SUHAM JUWAD KATHEM, LAMYA KHALIDI, KRISTA LEWIS, CARLOTTA MAHER†, AUGUSTA MCMAHON, JOHN C. SANDERS, JASON UR, T. J. WILKINSON†, KAREN L. WILSON, RICHARD L. ZETTLER, and PAUL C. ZIMMERMAN STUDIES IN ANCIENT ORIENTAL CIVILIZATION • VOLUME 71 THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO CHICAGO • ILLINOIS oi.uchicago.edu iv ISBN (paperback): 978-1-61491-063-3 ISBN (eBook): 978-1-61491-064-0 Library of Congress Control Number: 2021936579 ISSN: 0081-7554 The Oriental Institute, Chicago © 2021 by the University of Chicago. All rights reserved. Published 2021. Printed in the United States of America Series Editors Charissa Johnson, Steven Townshend, Leslie Schramer, and Thomas G. Urban with the assistance of Rebecca Cain and Emily Smith and the production assistance of Jalissa A. Barnslater-Hauck and Le’Priya White Cover Illustration Drawing: McGuire Gibson, Üçtepe, 1978, by Peggy Sanders Design by Steven Townshend Leaflet Drawings by Peggy Sanders Printed by ENPOINTE, Brooklyn Park, Minnesota, USA This paper meets the requirements of ANSI Z39.48-1984 (Permanence of Paper) ∞ oi.uchicago.edu v TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Abbreviations ................................................................................. vii Editor’s Note ........................................................................................ ix Introduction. Richard L. -

2007 Baseball Canada National Teams Awards Banquet & Fundraiser

2007 Baseball Canada National Teams Awards Banquet & Fundraiser Saturday, January 13, 2007 Dress - Business Casual 6:00 - 10:30 p.m. Contact: Northern Lights Ballroom Greg Hamilton Renaissance Toronto Downtown Head Coach & Director, (Rogers Centre) National Teams Program 3:30 p.m. Press Conference (Aurora Room) 9:00 p.m. Award Presentations & Videos 6:00 p.m. Cocktail Hour Emcee: Jerry Howarth, Toronto Blue Jays 7:45 p.m. Dinner 10:30 p.m. Auction & Autographs Award Winners Brett Lawrie Ernie Whitt Junior Team MVP Toronto Blue Jays & WBC Presented by Disney’s Special Recognition Award Wide World of Sports Mike Saunders Adam Stern Seattle Mariners Baltimore Orioles & WBC Senior National Team MVP Stubby Clapp Award Presented by Mizuno Jason Dickson Eric Gagne Canadian Olympic Team Texas Rangers Baseball Canada Alumni Award Special Achievement Award Presented by MLB Players Association Russell Martin Justin Morneau Los Angeles Dodgers Minnesota Twins Baseball Canada Alumni Award Special Achievement Award Presented by MLB Players Association Terry Puhl Houston Astros & Cdn Olympic Team Special Recognition Award Alumni Auction Silent Auction Including MLB and National Team Autographed Items MLB Alumni & Friends (Additional Alumni & Friends listed on www.baseball.ca) Paul Quantrill World Baseball Classic Al Schlazer Disney’s Wide World of Sports Jeff Francis Colorado Rockies Rob Ducey 2004 Olympic Team Adam Loewen Baltimore Orioles Pierre-Luc Laforest San Diego Padres Peter Orr Atlanta Braves Chris Robinson Chicago Cubs Scott Thorman Atlanta Braves Nick Weglarz Cleveland Indians Jamie Romak Atlanta Braves Paul Beeston Former C.O.O. MLB & Blue Jays Paul Godfrey Toronto Blue Jays Steve Rogers Montreal Expos & MLB Players Assoc. -

Ontario Quiz

Ontario Quiz Try our Ontario Quiz & see how well you know Ontario. Answers appear at the bottom. 1. On Ontario’s Coat of Arms, what animal stands on a gold and green wreath? A) Beaver B) Owl C) Moose D) Black Bear 2. On Ontario’s Coat of Arms, the Latin motto translates as: A) Loyal she began, loyal she remains B) Always faithful, always true C) Second to none D) Liberty, Freedom, Truth 3. Which premier proposed that Ontario would have its own flag, and that it would be like the previous Canadian flag? A) Frost B) Robarts C) Davis D) Rae 4. Ontario’s Progressive Conservative government under right wing leader Mike Harris espoused what kind of revolution? A) Law and order B) Tax deductions C) People first D) Common sense 5. Which of the following was not an Ontario Liberal leader? A) Jim Bradley B) Robert Nixon C) Mitch Hepburn D) Cecil Rhodes 6. Which of the following is not a recognized political party in Ontario? A) White Rose B) Communist C) Family Coalition D) Libertarian 7. Tim Hudak, leader of Ontario’s PC party is from where? A) Crystal Beach B) Fort Erie C) Welland D) Port Colborne 8. Former Ontario Liberal leader, Dalton McGuinty was born where? A) Toronto B) Halifax C) Calgary D) Ottawa 9. The first Ontario Provincial Police detachment was located where? A) Timmins B) Cobalt C) Toronto D) Bala 10. The head of the OPP is called what? A) Commissioner B) Chief C) Superintendent D) Chief Superintendent 11. Which of the following was not a Lieutenant Governor of Ontario? A) Hillary Weston B) John Aird C) Roland Michener D) William Rowe 12. -

In the Dominican Republic Eugenio D

World Languages and Cultures Publications World Languages and Cultures 6-2011 Sovereignty and Social Justice: The "Haitian Problem" In the Dominican Republic Eugenio D. Matibag Iowa State University, [email protected] Teresa Downing-Matibag Iowa State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/language_pubs Part of the Inequality and Stratification Commons, Latin American Languages and Societies Commons, Politics and Social Change Commons, and the Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons The ompc lete bibliographic information for this item can be found at http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ language_pubs/89. For information on how to cite this item, please visit http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ howtocite.html. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the World Languages and Cultures at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in World Languages and Cultures Publications by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sovereignty and Social Justice: The "Haitian Problem" In the Dominican Republic Abstract THE ISSUE OF DOMINICAN SOVEREIGNTY with regard to the rights of those of Haitian parentage seeking to secure Dominican nationality came to the fore recently in the case of Haitian rights activist Sonia Pierre. The ominicaD n Central Electoral Board produced evidence that Pierre’s parents obtained citizenship for their daughter, born on a sugar plantation in the Dominican Republic in 1963, by irregular means – that is, with forged documents. Legislator Vinicio A. Castillo Seman invoked the United Nations Assembly Resolution 869 IX General Assembly of 4 December 1975, Article 8, to the effect that the revocation of nationality can be justified in the cases in which it is proven that citizenship was obtained through fraud or false statements. -

2015 Baseball Canada National Teams Awards Banquet & Fundraiser

2015 Baseball Canada National Teams Awards Banquet & Fundraiser Saturday January 10th, 2015 Northern Lights Ballroom Renaissance Toronto Downtown (Rogers Centre) Program 3:30 p.m. Press Conference (Aurora Room) 9:15 p.m. Award Presentations & Videos 6:00 p.m. Cocktail Hour 10:45 p.m. Autographs 7:45 p.m. Dinner Emcee: Mike Wilner, Sportsnet - 590 The Fan Award Winners Gareth Morgan Josh Naylor Seattle Mariners Junior National Team Junior National Team MVP Canadian Futures Award Presented by ESPN Wide World of Sports Presented by The Toronto Chapter of BBWAA Justin Morneau Jamie Romak Colorado Rockies Los Angeles Dodgers Stubby Clapp Award Special Achievement Award Presented by Mizuno Canada Presented by MLB Players Association Jeff Francis Roberto Alomar Toronto Blue Jays Toronto Blue Jays Baseball Canada Alumni Award Special Recognition Award Presented by L.J. Pearson Foundation Presented by MLB Players Association Russell Martin Toronto Blue Jays Wall of Excellence Presented by RBC Wealth Management Alumni Auction • Live & Silent Auction Including MLB and National Team Autographed Items • Ryan Dempster Cubs Fantasy Package For Four People – Spend A Day with Ryan ( 3 Game Series at Wrigley, 3 Nights Hotel, 2 Dinners - Clubhouse, Scoreboard & Broadcast Booth Tours with Ryan, On field Batting Practice with Ryan, Lunch & Dinner with Ryan ) MLB Alumni & Friends (Additional Alumni & Friends listed on www.baseball.ca) ! Larry Walker St. Louis Cardinals & WBC ! Joey Votto Cincinnati Reds & WBC ! John Axford Pittsburgh Pirates & WBC ! Mike Saunders -

Honour and Care

Honourand Care Spring 2018 A Blessed Life By Peter McKinnon everal birthday cards adorn Edith Goodspeed’s room at the Perley and Rideau Veterans’ Health Centre, marking her recent birthday. “This was Snumber 99,” she says with a smile, “for all my future birthdays, I won’t count any higher…I’ll just stay 99.” Edith has certainly earned the right to lie about her age. As a Nursing Sister in England during the Second World War, she experienced the horrors of Nazi bombing and helped countless soldiers recover enough to return home or back into battle. She later raised three children and today is blessed with seven grandchildren and two great grandchildren. Born in 1919 as the second child of a farm family in Rosetown, Saskatchewan, Edith Mary Ferrall was named after her aunt. Edith’s father died before she was three; her mother sold the farm and raised Edith and her brother Arthur in Cypress River, Manitoba. “My parents both worked hard and did a lot for the community,” she recalls. Edith Goodspeed “I remember Dad organizing baseball games and inviting the players home See page 2 Ted Griffiths’ Journey of Reconciliation Contents By Peter McKinnon 3 Women and Strength 6 Daniel Clapin column ajor (ret'd) Edmund (Ted) Griffiths, CD, now spends much of his time 7 The People of Beechwood reading, chatting with fellow Veterans and other residents of the Perley 14 Once a Runner, Always a Runner Mand Rideau Veterans’ Health Centre, and visiting with his family: a 15 Ottawa Race Weekend daughter, eight grandchildren and eight great-grandchildren. -

A CELEBRATION of Genius the CBC Marks the Tercentenaries of George Frideric Handel and Johann Sebastian Bach

FEBRUARY 1985 $1.75 A CELEBRATION of GENIus The CBC marks the tercentenaries of George Frideric Handel and Johann Sebastian Bach David Hayes on David Essig = Disaster strikes! _ .- John Julianu's'nerrseries begins . :04(0)," -t Wi'.-- f ¡ - { ' d To Nakamichi, Convenience without performance is unthinkable. - "\, 11~ \ / 7e °h LL-C-)-- Now you have a choice of sides of the cassette auto- I- F I three Nakamichi Auto - w matically. Auto Rec Standby Reverse Cassette simplifies recording decks -each with ----- setup on each side UDAR, Nakamichi's while a Dual -Speed revolutionary Unidirec- Master Fader helps you tional Auto Reverse make truly professional mechanism that elimi- tapes. Direct Operation nates bidirectional azimuth loads and initiates the de- error and assures you of 20- sired function at a touch, and 20,000 Hz response on both - Auto Skip provides virtually con- sides of the cassette. tinuous playback! UDAR is simple, fast, and reliable. It automates UDAR-the revolutionary auto -reverse record- the steps you perform on a conventional one-way ing and alayback system -only from Nakamichi. deck. At the end of each side, UDAR disengages Check out the RX Series now at your local Naka- the cassette, flips it, reloads, and resumes oper- michi deale-. One audition will convince you ation in under 2 seconds. Tape plays in the same there's np longer a reason to sacrifice unidirec- direction on Side A and on Side B so perfor- tional performance for auto -reverse convenience! mance is everything you've come to expect from W. CARSEN CO. LTD. 25 SCARSDALE ROAD, DON MILLS. -

Osman Hamdi Bey and the Americans: Archaeology, Diplomacy, Art

Annika K. Johnson exhibition review of Osman Hamdi Bey and the Americans: Archaeology, Diplomacy, Art Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 11, no. 3 (Autumn 2012) Citation: Annika K. Johnson, exhibition review of “Osman Hamdi Bey and the Americans: Archaeology, Diplomacy, Art,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 11, no. 3 (Autumn 2012), http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/autumn12/johnson-reviews-osman-hamdi-bey-and-the- americans. Published by: Association of Historians of Nineteenth-Century Art. Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. Johnson: Osman Hamdi Bey and the Americans: Archaeology, Diplomacy, Art Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 11, no. 3 (Autumn 2012) Osman Hamdi Bey and the Americans: Archaeology, Diplomacy, Art The Suna and Inan Kıraç Foundation Pera Museum, Istanbul October 14, 2011 – January 8, 2012 Archaeologists and Travelers in Ottoman Lands University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia September 26, 2010 – June 26, 2011 Catalogue: Osman Hamdi Bey and the Americans: Archaeology, Diplomacy, Art (Osman Hamdi Bey & Amerikalilar: Arkeoloji, Diplomas, Sanat) Edited by Renata Holod and Robert Ousterhout, with essays by Renata Holod, Robert Ousterhout, Susan Heuck Allen, Bonna D. Wescoat, Richard L. Zettler, Jamie Sanecki, Heather Hughes, Emily Neumeier, and Emine Fetvaci. Istanbul: Pera Museum Publication, 2011. 411 pp.; 96 b/w; 119 color; bibliography 90TL (Turkish Lira) ISBN 978-975-9123-89-5 The quietly monumental exhibition, titled Osman Hamdi Bey and the Americans: Archaeology, Diplomacy, Art, was the product of a surprising collaboration between the Suna and Inan Kıraç Foundation Pera Museum in Istanbul and the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology in Philadelphia. -

C Augus Deficit St Trad Hits $ Ie

iT l ( m Good morningr D o th e ‘EHokey Poke};y’ aind ... I']Fry: Ta:IX hike mightn Today’s forec:ecast: Sunny with highighs in the mid- to upper ------------ fiOfi^LowK-in-Jhe-m5 mid-30s:---------------------^— ___________ follow plajsiiagejofA%_ Page A2 TheTl Times-News about the 1 Perci’ercent Initiative, the ballot measure lhalJl ilif passed would liinil TWIN I-ALLS - An id;ihc.ho slale lax properly laxeses tot I pereent of market commissioner predicted Frida,Jay lhal the value, mmm Lc Legislature will have lilile chi)hoice hui lo lie eniphasi/esi/ed lhai both lie and the , Construction»n begins niisenii laxes ne.xl winter if iliee 1 Percent rest o f the taxIX cuniniissionc are iieulra) IniliiiliveIni passes ihis fall. on the issue. '■ The band playedi'cd and colored balloons "rve heard a number of' legislatorsli Alan Domfesi.fesl. a tax policy spccialisl rose as WendellI patronsp; celebrated the saysa) thal (they won’i alleinptpt lo offset wilh the commis:mission, has estimated that b7art o f eo n struiction cti of the new high llic _schooI Friday. llie loss in properly tax revevenue w-ith the 1 Percent’st's passagef will com local Page Bl slaleslil revenue if the iniiativee passes)." governm ents: andam si'luiol districts ilial , '1® RobertRo i-'r)’ said following a speechsp to a depend on propeiopeny taxes heiwcen SII-} conference on aging al the TTi urf Club, and S150 millionlion a year. Old news "I^ "Bui realistically, I ihink theIlCR- would ..o r ,.......„p,iopiions I've heard.