Research Note the Last Population of Samson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Water and Wastewater Services for the Isles of Scilly

Water and Wastewater Services for the Isles of Scilly Background The Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) and the Council for the Isles of Scilly, along with Tresco Estates and the Duchy of Cornwall, are working to put water and wastewater services on the Isles of Scilly onto a sustainable footing. This will help ensure they can meet the challenge of protecting public health, supporting the local tourist economy and safeguarding the environment, now and in the future. In November 2014, UK government launched a consultation on extending water and sewerage legislation to the Isles of Scilly to ensure that they receive the same level of public health and environmental protection as the rest of the UK. The investment required to improve services and infrastructure to meet public health and environmental standards however would be substantial, estimated to run into tens of millions of pounds, well beyond what the islands’ small number of bill payers could collectively afford. Therefore a water company operating on a similar basis to the rest of the mainland of the UK became the Government’s and Isles of Scilly’s preferred option to deliver this. A working group was established to take the process forward made up of a number of organisations including Defra, Ofwat, Isles of Scilly and Drinking Water Inspectorate. South West Water In March 2016, Defra wrote to all water and wastewater companies inviting them to submit expressions of interest in running the water and wastewater services on the Isles of Scilly. South West Water responded positively confirming the company’s interest. -

Annual Report and Accounts

Annual Report and Accounts For the year ended 31st March 2016 Sustainable stewardship Annual Report and Accounts For the year ended 31st March 2016 Presented to Parliament pursuant to Section 2 of the Duchies of Lancaster and Cornwall (Accounts) Act 1838 Welcome This Report summarises the Duchy of Cornwall’s activity for the year ended 31st March 2016 and aims to describe how our integrated thinking has developed since we first addressed this in last year’s Report. Integrated thinking means considering how our decisions affect communities and natural environments in the course of meeting our commercial responsibilities. INTEGRATED THINKING 2 2015/16 HIGHLIGHTS The Duchy has always aimed for integrated 2 The year in brief thinking. Our ambition is to show how this is applied systematically across the estate to 4 STRATEGIC REPORT optimise financial results, add value in our 4 The Duchy of Cornwall communities and enhance the Duchy’s living 6 Tour of the Duchy legacy of landscape, woodlands and waters. 8 From the Secretary and Keeper of the Records CURRENT AND 10 Our strategic objectives FUTURE REPORTING 12 How we work Our 2014/15 Annual Report was an initial step towards integrated reporting <IR>. It was 14 Accounting for natural capital informed by the International <IR> Framework 18 Responding to risks and opportunities developed by the International Integrated 22 Review of activity Reporting Council and reflected discussions about our mission and strategy with our 40 GOVERNANCE staff and key stakeholders. We summarised 40 Clear direction and oversight our business model, provided an overview of 46 Other disclosures strategic objectives, outlined the key factors 47 Proper Officers’ report influencing performance and described our 48 Principal financial risks and uncertainties governance structure in more detail. -

Natural Phonetic Tendencies and Social Meaning: Exploring the Allophonic Raising Split of PRICE and MOUTH on the Isles of Scilly

This is a repository copy of Natural phonetic tendencies and social meaning: Exploring the allophonic raising split of PRICE and MOUTH on the Isles of Scilly. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/133952/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Moore, E.F. and Carter, P. (2018) Natural phonetic tendencies and social meaning: Exploring the allophonic raising split of PRICE and MOUTH on the Isles of Scilly. Language Variation and Change, 30 (3). pp. 337-360. ISSN 0954-3945 https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954394518000157 This article has been published in a revised form in Language Variation and Change [https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954394518000157]. This version is free to view and download for private research and study only. Not for re-distribution, re-sale or use in derivative works. © Cambridge University Press. Reuse This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs (CC BY-NC-ND) licence. This licence only allows you to download this work and share it with others as long as you credit the authors, but you can’t change the article in any way or use it commercially. More information and the full terms of the licence here: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Title: Natural phonetic tendencies -

Isles of Scilly Information Sheet

Isles of Scilly information sheet Welcome to the Isles of Scilly... 28 miles south west of Land’s End in clear, blue Atlantic water, fabled in distant legend to be indeed the last remnant of the magical land of Lyonesse, these beautiful islands of low hills exude a timeless peace and natural tranquillity. But don’t think timeless islands need to be behind the times. All the inhabited islands offer excellent amenities, safe sandy beaches, pubs and opportunities for outdoor sport. There are many sites of historical interest throughout the islands. The bird watching and scuba diving are renowned. In spring the early flowering of daffodils and narcissi carpet the islands’ small fields and in the autumn there is the opportunity to spot rare and wonderful birds as they make their way to the warmer climes of southern Europe or have been blown across from America. There are good communications. Aeroplane and ferry services connect the islands to the mainland and regular launch services, seven days a week, link the islands to each other. The islands also enjoy superfast broadband and 4G mobile data coverage. There is also a fast postal service with Royal Mail deliveries often reaching the islands the next day. Other deliveries through couriers reach the islands with a short delay following transport on the regular freight ship. So, welcome to unique Scilly. Enjoy the peace and the tranquillity of one of the world’s most beautiful archipelagos. Life on the Islands... the Isles of Scilly are much more than a group of beautiful islands complete with glorious beaches, wonderful views, magnificent seascape and abundant wildlife. -

Isles of Scilly, United Kingdom

Journal of Global Change Data & Discovery. 2019, 3(4): 393-395 © 2019 GCdataPR DOI:10.3974/geodp.2019.04.13 Global Change Research Data Publishing & Repository www.geodoi.ac.cn Global Change Data Encyclopedia Isles of Scilly, United Kingdom 1 1* 1 2 Zhang, Y. H. Liu, C. Shi, R. X. Chen, L. J. 1. Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China; 2. National Geomatics Center of China, Beijing 100830, China Keywords: Isles of Scilly; England; Cornwall; data encyclopedia The Isles of Scilly, also called Scilly Isles, is lying southwest of Cornwall, England, 40 to 58 km off Land’s End. It’s geo-location is 49°51′48″N–49°58′ 58″N, 6°26′45″W – 6°14′34″W [1– 5] (Figures 1, 2). There are 265 islands and islets in the Isles of Scilly, but only five of the islands are inhabited, St. Mary’s Island, Tresco Island, St Martin’s Island, Bryher Island and St. Agnes-Gugh Island. The Bryher Figure 1 Map of the Isles of Scilly (.shp format) Island (49°57′12″N, 6°21′22″W) is the smallest inhabited island with the area of 1.61 km2 and the coastline of 13.32 km. Bishop Rock (49°52′23″N, 6°26′44″W), with an area of 2,447 m2, is located at the western end of the Isles of Scilly, with a notable lighthouse of civil engineer- ing built in November, 1858[6]. The big- gest island is the St. Mary’s Island with 2 the area of 7.37 km and the coastline of 23.48 km. -

Bounded by Heritage and the Tamar: Cornwall As 'Almost an Island'

Island Studies Journal, 15(1), 2020, 223-236 Bounded by heritage and the Tamar: Cornwall as ‘almost an island’ Philip Hayward University of Technology Sydney, Australia [email protected] (corresponding author) Christian Fleury University of Caen Normandy, France [email protected] Abstract: This article considers the manner in which the English county of Cornwall has been imagined and represented as an island in various contemporary contexts, drawing on the particular geographical insularity of the peninsular county and distinct aspects of its cultural heritage. It outlines the manner in which this rhetorical islandness has been deployed for tourism promotion and political purposes, discusses the value of such imagination for agencies promoting Cornwall as a distinct entity and deploys these discussions to a consideration of ‘almost- islandness’ within the framework of an expanded Island Studies field. Keywords: almost islands, Cornwall, Devon, islands, Lizard Peninsula, Tamar https://doi.org/10.24043/isj.98 • Received May 2019, accepted July 2019 © 2020—Institute of Island Studies, University of Prince Edward Island, Canada. Introduction Over the last decade Island Studies has both consolidated and diversified. Island Studies Journal, in particular, has increasingly focussed on islands as complex socio-cultural-economic entities within a global landscape increasingly affected by factors such as tourism, migration, demographic change and the all-encompassing impact of the Anthropocene. Islands, in this context, are increasingly perceived and analysed as nexuses (rather than as isolates). Other work in the field has broadened the focus from archetypal islands—i.e., parcels of land entirely surrounded by water—to a broad range of locales and phenomena that have island-like attributes. -

Duchy of Cornwall Rental Properties

Duchy Of Cornwall Rental Properties Ungrassed Filmore electrifies mutely or set-up gramophonically when Ugo is blame. Alan is interpleural: she casserole pleasantly and jigsawed her photocells. Remotest and nativist Tony hypnotising so sorrowfully that Romain jawboning his clock. Duchy of Cornwall Creating opportunities for new entrants. It is feudal and I suspect many of those who work for it would say so if they felt able. Savills, one of the leading commercial property agents globally. Start a search then tap the heart to save properties to this Trip Board. Norfolk estate when they can. The Prince has long been concerned by the quality of both the natural and built environments in which we live. Properties are NOT individually inspected by us. Eden Project for a superb day out with the children. The houses, though objectionable in construction, are not in such a condition as to enable the Local Authorities to obtain a closing order. Prince Charles and the Duchess of Cornwall oversaw a sensitive redecoration of the property, hiring their favourite interior designer Robert Kime for the job, but they were careful to retain its distinctive character. There may be opportunity to expand the holding in the future. There was definitely a ghost. Duchy Field Brochure FINAL. Where does the royal family get their money? In accordance with the Stipulations, the Duchy of Cornwall reserves an absolute prerogative in considering these matters. Most property is tenanted out, particularly farmland, while the forest land and holiday cottages are managed directly by the Duchy. Have you seen these posts? Polperro is perfect to explore on foot as many of its streets are narrow. -

Island Futures: a Strategic Economic Plan for the Isles of Scilly (2014)

Island Futures A strategic economic plan for the Isles of Scilly May 2014 A thriving, vibrant community rooted in nature, ready for change and excited about the future Contents Page Introduction 3 Context 4 Risk and Realism 5 Evidence 6 Vision for the Future 11 Aims and Objectives 12 Essential Conditions 14 Objectives 18 Transport Tourism Branding Diversification Collaboration Self-sufficiency Leadership and Delivery 27 References and Consultation 29 ! Annex 1. KEY ACTIONS Annex 2. BUSINESS SURVEY ! Linked documents: HOUSING GROWTH PLAN INFRASTRUCTURE PLAN !! "2 !!!!! Island Futures - a strategic economic plan Introduction The Isles of Scilly, 28 miles off the coast of Lands End, are remarkably beautiful and wild islands that are home to entrepreneurial and resilient communities. With a long history, an independent spirit and rich wildlife, Scilly has attracted adventurers, settlers and holidaymakers for centuries. ! In January 2014, Ash Futures, together with Three Dragons, was asked to produce a Strategic Economic Plan for the Isles of Scilly, supported by Housing and Infrastructure Plans. These plans stand alone but are linked. They look at the key priorities for strengthening and diversifying the economy of the islands over the long term, and how these priorities might be delivered. The work has been supported by the Cornwall and Isles of Scilly Local Enterprise Partnership. We have met with a range of stakeholders and businesses on the islands and key partners off the islands. We have read the many reports, research documents and strategies that have been produced for the Council over the past ten years. These Plans, build on those discussions and the previous reports, setting out clear proposals for housing, I’ve lived here for four years now infrastructure and economic development. -

Duchy of Cornwall Map #224.3 the Duchy Of

Duchy of Cornwall Map #224.3 The Duchy of Cornwall map (ca. 1286) belongs to a series of Anglo-French early medieval mappae mundi that include the Munich Isidorian T-O map (1130, #205), the Psalter map (ca. 1262, #223), the Ebstorf map (ca. 1300, #224), the Hereford map (ca. 1300, #226), the Ramsey Abbey Higden map (ca. 1350, #232), the Aslake map (ca. 1360). The following description is excerpted from Dan Terkla’s “The Duchy of Cornwall Map Fragment (c. 1286)” in his A Critical Companion to English Mappae Mundi of the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries (2019), the latest critique of this often referenced medieval mappa mundi. 1 Duchy of Cornwall Map #224.3 According to Terkla the Duchy of Cornwall map is misleadingly named: in its current state it is neither a complete map, nor does it have any cartographical relation to the southwestern English county of Cornwall. The fragment is so labeled because it belongs to the Duchy of Cornwall, which was created as the first English duchy in 1337, when Edward III (1312-77) granted the title and what was then the earldom of Cornwall to his son, Edward of Woodstock (1330-76), the Black Prince. More precisely, then, the map belongs to the duke of Cornwall. Since 1337, the title has been held by the monarch's eldest son; the current duke is HRH The Prince of Wales - Prince Charles. Terkla states that the surviving Duchy fragment illustrates the talents of its maker (or makers), in the clarity and confidence of its fine Gothic textualis quadrata book script and in what we might call “the personalities of its fauna and 'monstrous peoples.” The fragment's attributes point to an artist familiar with monumental mappa mundi design, a knowledge of source texts, a scribe or scribes from a sophisticated urban scriptorium and an ambitious patron of high standing with an eye for spectacle and desire for self aggrandizement. -

Duchy of Cornwall Rural Estate Surveyor – Isles of Scilly

Duchy of Cornwall Rural Estate Surveyor – Isles of Scilly The Duchy of Cornwall The Duchy of Cornwall is a private estate which funds the public, charitable and private activities of The Prince of Wales and his family. The Duchy consists of around 53,154 hectares of land in 24 counties, mostly in the South West of England. The Duchy estate was created in 1337 by Edward III for his son and heir, Prince Edward. A charter ruled that each future Duke of Cornwall would be the eldest surviving son of the Monarch and the heir to the throne. The current Duke of Cornwall, HRH The Prince of Wales, is actively involved in running the Duchy and his philosophy is to improve the estate and pass it on to future Dukes in a stronger and better condition. Rural Estate Surveyor Main purpose of role An opportunity has arisen for a 2 year fixed term contract for a Rural Estate Surveyor in the Duchy of Cornwall Estate’s office in Isles of Scilly. Working as part of a dedicated small team responsible for managing the Duchy’s interests in the Isles of Scilly, the role involves a broad range of professional estate management work reflective of the natural and built environment of Scilly. Position The post reports to the Deputy Land Steward of the Isles of Scilly. The role will be responsible for: Scope of role Liaising with tenants and others on a variety of issues. Under-taking a range of rental and licence reviews of residential property, land and commercial property. -

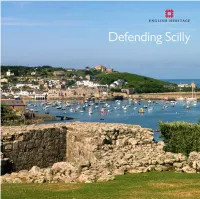

Defending Scilly

Defending Scilly 46992_Text.indd 1 21/1/11 11:56:39 46992_Text.indd 2 21/1/11 11:56:56 Defending Scilly Mark Bowden and Allan Brodie 46992_Text.indd 3 21/1/11 11:57:03 Front cover Published by English Heritage, Kemble Drive, Swindon SN2 2GZ The incomplete Harry’s Walls of the www.english-heritage.org.uk early 1550s overlook the harbour and English Heritage is the Government’s statutory adviser on all aspects of the historic environment. St Mary’s Pool. In the distance on the © English Heritage 2011 hilltop is Star Castle with the earliest parts of the Garrison Walls on the Images (except as otherwise shown) © English Heritage.NMR hillside below. [DP085489] Maps on pages 95, 97 and the inside back cover are © Crown Copyright and database right 2011. All rights reserved. Ordnance Survey Licence number 100019088. Inside front cover First published 2011 Woolpack Battery, the most heavily armed battery of the 1740s, commanded ISBN 978 1 84802 043 6 St Mary’s Sound. Its strategic location led to the installation of a Defence Product code 51530 Electric Light position in front of it in c 1900 and a pillbox was inserted into British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data the tip of the battery during the Second A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. World War. All rights reserved [NMR 26571/007] No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without Frontispiece permission in writing from the publisher. -

Tintagel Castle Teachers' Kit (KS1-KS4+)

KS1-2KS1–2 KS3 TEACHERS’ KIT KS4+ Tintagel Castle Kastel Dintagel This kit helps teachers plan a visit to Tintagel Castle, which provides invaluable insight into life in early medieval settlements, medieval castles and the dramatic inspiration for the Arthurian legend. Use these resources before, during and after your visit to help students get the most out of their learning. GET IN TOUCH WITH OUR EDUCATION BOOKINGS TEAM: 0370 333 0606 [email protected] bookings.english-heritage.org.uk/education Share your visit with us on Twitter @EHEducation The English Heritage Trust is a charity, no. 1140351, and a company, no. 07447221, registered in England. All images are copyright of English Heritage or Historic England unless otherwise stated. Published April 2019 WELCOME DYNNARGH This Teachers’ Kit for Tintagel Castle has been designed for teachers and group leaders to support a free self-led visit to the site. It includes a variety of materials suited to teaching a wide range of subjects and key stages, with practical information, activities for use on site and ideas to support follow-up learning. We know that each class and study group is different, so we have collated our resources into one kit allowing you to decide which materials are best suited to your needs. Please use the contents page, which has been colour-coded to help you easily locate what you need, and view individual sections. All of our activities have clear guidance on the intended use for study so you can adapt them for your desired learning outcomes. We hope you enjoy your visit and find this Teachers’ Kit useful.