Sustainability and Visitor Management in Tourist Historic Cities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

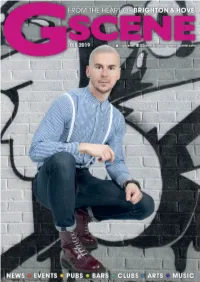

02 Gscene Feb2019

FEB 2019 CONTENTS GSCENE magazine ) www.gscene.com AFFINITY BAR t @gscene f GScene.Brighton PUBLISHER Peter Storrow TEL 01273 749 947 EDITORIAL [email protected] ADS+ARTWORK [email protected] EDITORIAL TEAM James Ledward, Graham Robson, Gary Hart, Alice Blezard, Ray A-J SPORTS EDITOR Paul Gustafson N ARTS EDITOR Michael Hootman R E SUB EDITOR Graham Robson V A T SOCIAL MEDIA EDITOR E N I Marina Marzotto R A DESIGN Michèle Allardyce M FRONT COVER MODEL Arkadius Arecki NEWS INSTAGRAM oi_boy89 SUBLINE POST-CHRISTMAS PARTY FOR SCENE STAFF PHOTOGRAPHER Simon Pepper, 6 News www.simonpepperphotography.com Instagram: simonpepperphotography f simonpepperphotographer SCENE LISTINGS CONTRIBUTORS 24 Gscene Out & About Simon Adams, Ray A-J, Jaq Bayles, Jo Bourne, Nick Boston, Brian Butler, 28 Brighton & Hove Suchi Chatterjee, Richard Jeneway, Craig Hanlon-Smith, Samuel Hall, Lee 42 Solent Henriques, Adam Mallaby, Enzo Marra, Eric Page, Del Sharp, Gay Socrates, Brian Stacey, Michael Steinhage, ARTS Sugar Swan, Glen Stevens, Duncan Stewart, Craig Storrie, Violet 46 Arts News Valentine (Zoe Anslow-Gwilliam), Mike Wall, Netty Wendt, Roger 47 Arts Matters Wheeler, Kate Wildblood ZONE 47 Arts Jazz PHOTOGRAPHERS Captain Cockroach, James Ledward, 48 Classical Notes Jack Lynn, Marina Marzotto 49 Page’s Pages REGULARS 26 Dance Music 26 DJ Profile: Lee Dagger 45 Shopping © GSCENE 2019 All work appearing in Gscene Ltd is 52 Craig’s Thoughts copyright. It is to be assumed that the copyright for material rests with the magazine unless otherwise stated on the 53 Wall’s Words page concerned. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in 53 Gay Socrates an electronic or other retrieval system, transmitted in any form or by any means, 54 Charlie Says electronic, mechanical, photocopying, FEATURES recording or otherwise without the prior 55 Hydes’ Hopes knowledge and consent of the publishers. -

SUMMER 2010 ASSEMBLY REPORTS District Assemblies Were Held Over the Weekend 12Th-15Th March in Morley and Paisley

CHURCH OF THE NAZARENE Together “Since we are all one body in Christ, we belong to each other and each of us needs all the others” (Romans 12:5) British Isles – – – SUMMER 2010 ASSEMBLY REPORTS District Assemblies were held over the weekend 12th-15th March in Morley and Paisley. South District Superintendent, Rev David Montgomery, brought his first report to the Assembly with the challenge to “…remain in Christ”. As Jesus said, “…if a man remains in me and I in him, he will bear much fruit…” (John 15:5). Special features of the assembly were the times of prayer for each pastor, and a question and answer session with members of the District Advisory Board. A weekend of Conventions and Rallies characterised the North Assembly, Times of Prayer at the South Assembly which followed the theme, The Church in Community, Evangelism, Worship, & Mission. Rev Colin H. Wood, brought his 18th report as District Superintendent and recognised the great need for God’s Spirit to move in the land and across the district, and that God’s Call would come to many to offer themselves for the pastoral ministry. General Superintendent, Dr Jesse C. Middendorf, presided at both assemblies, Ordination group Morley (l.to r.) Rev and both assemblies David Montgomery, Rev Margaret concluded with ordination Brown (Ordinand – Atherton), Dr Jesse C. Ordination group Paisley standing (l.to r.): Rev Jonny & services. Middendorf. Pamela Gios (Carlisle), Rev Derrick & Dayna Thames (Perth), Rev Rosemary Davidson (Edinburgh), Rev Michelle Sowerby (Parkhead), Rev Jennifer & Pastor Jonny Blake (Carlisle), JoAnne & Rev Nathan Payne (Erskine). -

Benidorm Spain Travel Guide

Benidorm Costa Blanca - Spain Travel Guide by Doreen A. Denecker and Hubert Keil www.Alicante-Spain.com Free Benidorm Travel Guide This is a FREE ebook! Please feel free to : • Reprint this ebook • Copy this PDF File • Pass it on to your friends • Give it away to visitors of your website*) • or distribute it in anyway. The only restriction is that you are not allowed to modify, add or extract all or parts of this ebook in any way (that’s it). *) Webmaster! If you have your own website and/or newsletter, we offer further Costa Blanca and Spain material which you can use on your website for free. Please check our special Webmaster Info Page here for further information. DISCLAIMER AND/OR LEGAL NOTICES: The information presented herein represents the view of the author as of the date of publication. Be- cause of the rate with which conditions change, the author reserves the right to alter and update his opinion based on the new conditions. The report is for informational purposes only. While every at- tempt has been made to verify the information provided in this report, neither the author nor his affili- ates/partners assume any responsibility for errors, inaccuracies or omissions. Any slights of people or organizations are unintentional. If advice concerning legal or related matters is needed, the services of a fully qualified professional should be sought. This report is not intended for use as a source of legal or accounting advice. You should be aware of any laws which govern business transactions or other business practices in your country and state. -

ATINER's Conference Paper Series TOU2012-0116 Public Opinions Of

ATINER CONFERENCE PAPER SERIES No: TOU2012-0116 Athens Institute for Education and Research ATINER ATINER's Conference Paper Series TOU2012-0116 Public Opinions of Stakeholders of Benidorm (Spain) Tomás Mazón Full Time Professor University of Alicante, Spain Elena Delgado Laguna Doctoral Candidate in Sociology of Tourism University of Alicante Spain 1 ATINER CONFERENCE PAPER SERIES No: TOU2012-0116 Athens Institute for Education and Research 8 Valaoritou Street, Kolonaki, 10671 Athens, Greece Tel: + 30 210 3634210 Fax: + 30 210 3634209 Email: [email protected] URL: www.atiner.gr URL Conference Papers Series: www.atiner.gr/papers.htm Printed in Athens, Greece by the Athens Institute for Education and Research. All rights reserved. Reproduction is allowed for non-commercial purposes if the source is fully acknowledged. ISSN 2241-2891 6/09/2012 2 ATINER CONFERENCE PAPER SERIES No: TOU2012-0116 An Introduction to ATINER's Conference Paper Series ATINER started to publish this conference papers series in 2012. It includes only the papers submitted for publication after they were presented at one of the conferences organized by our Institute every year. The papers published in the series have not been refereed and are published as they were submitted by the author. The series serves two purposes. First, we want to disseminate the information as fast as possible. Second, by doing so, the authors can receive comments useful to revise their papers before they are considered for publication in one of ATINER's books, following our standard procedures of a blind review. Dr. Gregory T. Papanikos President Athens Institute for Education and Research 3 ATINER CONFERENCE PAPER SERIES No: TOU2012-0116 This paper should be cited as follows: Mazón, T. -

Poleroid Theatre Presents PLASTIC by Kenneth Emson

Poleroid Theatre presents PLASTIC By Kenneth Emson TOURING SPRING-SUMMER 2017 A shitty little town in Essex. A summer’s day. Amid the prefect badges and empty B&H packets, a secret lurks that will send shivers down the spine of a small community. By award-winning television and screen writer Kenneth Emson, Plastic is an extraordinary, heady mix of drama and performance poetry, a dynamic new verse play looking at the musicality in the everyday; the first moments of adulthood, the hard edge of school abuse, the creation of urban folklore and the seemingly random moments that come to define our adult lives. Today’s the day Yes it is Reebok Classic of a day today Yes. It. Is. Directed by Josh Roche (RSC/Globe/nabokov/Finborough) and produced by acclaimed, triple Off West End Theatre Award- nominated Poleroid Theatre, Plastic previewed to a packed house at Latitude Festival 2015. Plastic’s debut production starred Katie Bonna (Dirty Great Love Story), James Cooney (Bottleneck), Adam Gillen (Benidorm/Fresh Meat) and Scott Hazell (Mudlarks). ‘Top of this week’s list for all theatre-goers.’ Bargain Theatre London ‘An extraordinary piece of theatre’ Female Arts ‘Touching and beautifully written’ Postscript Journal We are now planning an extensive small-scale UK tour in Spring-Summer 2017, with support from the Mercury Theatre in Colchester and High House Production Park in Thurrock, pending an ACE application. We are seeking expressions of interest/pencilled dates from venues. We have already created key marketing resources including marketing and print designs, a video trailer and press imagery. -

Page 1 of 115 WELCOME Welcome to the Theatre Royal & Royal Concert

WELCOME Welcome to the Theatre Royal & Royal Concert Hall’s season brochure, covering February to May 2019. IMPORTANT BOOKING INFORMATION Please be aware that bookings are subject to fees, unless stated otherwise, and that discounts may not be available for certain seating areas and performances. Customers with disabilities, we recommend you check the availability of discounts at the time of booking. Please contact the Box Office for further details. Where fees apply, it is £3 per transaction for orders in person and by phone, £2 per transaction online. Further details are on our website - trch.co.uk/fees. AN UPDATE FROM EMILY MALEN Hello and welcome to the Nottingham Theatre Royal and Royal Concert Hall's events listing for February to May 2019. Page 1 of 115 This listing includes details of forthcoming productions at the Theatre Royal and Royal Concert Hall and well as venue news and information. Forthcoming sign language interpreted performances include RSC’s Romeo & Juliet, Friday 22 February at 7.30pm. Semi-integrated signer provided by RSC. Benidorm Live, Wednesday 27 March at 7.30pm. Interpreted by Laura Miller. Rock of Ages, Thursday 4 April at 7.30pm. Interpreted by Caroline Richardson. Motown the Musical, Thursday 25 April at 7.30pm. Interpreted by Donna Ruane. Forthcoming captioned performances include The Full Monty, Saturday 9 February at 7.30pm. Captioned by Stagetext Page 2 of 115 RSC’s Romeo & Juliet, Saturday 23 February at 1.30pm. Captioned by the RSC. Opera North – The Magic Flute, Saturday 23 March at 7pm. Captioned by Opera North. Benidorm Live, Thursday 28 March at 7.30pm. -

[email protected] BOOKING LINE: 020 3258 3019 U

BOOKING LINE: 020 3258 3019 u PROGRAMME Magic Moments Showcoaches and Tours ISSUED Booking Line: 020 3258 3019 Nov 16th 2018 Website: www.magicmomentstours.co.uk E-Mail: [email protected] QUALITY TOURS WITH A PERSONAL TOUCH HOW TO BOOK YOUR MAGIC MOMENTS TOUR Simply call us on 020 3258 3019 and we’ll take all your details over the telephone. We will then send you a confirmation invoice through the post. Alternatively you can pay by cheque in which case, you can either forward us a cheque at the address below with your booking request (please check tour availability first). Or pay via credit / debit card at the time of booking to secure your seats. MAGIC MOMENTS SHOWCOACHES and TOURS 35 Newbury Gardens, Stoneleigh, Epsom, Surrey KT19 0NS Website: www.magicmomentstours.co.uk E-Mail: [email protected] BOOKING LINE: 020 3258 3019 u SHOWCOACH & DAY TOUR ROUTE NUMBERS ROUTE A ASHTEAD, High Street – EPSOM, Clocktower EWELL, Mongers Lane – EWELL Spring Street EXPRESS (In-between Stops may not be offered on this Route) ROUTE B ASHTEAD, High Street -THE WELLS, Spa Drive EPSOM, Clocktower - EWELL, Mongers Lane EWELL Spring Street ROUTE C ASHTEAD, High Street - EPSOM, Clocktower EWELL, Mongers Lane - EWELL Spring Street EWELL, Bradford Drive - EWELL, Ruxley Lane ROUTE D ASHTEAD, High Street - THE WELLS, Spa Drive EPSOM, Clocktower - EWELL, Mongers Lane EWELL Spring Street - EWELL, Bradford Drive EWELL, Ruxley Lane In addition we may also be able to offer the following pick up points if requested Please enquire at time -

MARK BROTHERHOOD Current LUDWIG Treatment and Script

MARK BROTHERHOOD Current LUDWIG Treatment and script optioned to Hat Trick. MY GENERATION Original pilot script optioned to Hare & Tortoise. CHILDREN OF THE STONES Written treatment and script commissioned by Vertigo Films. RENDLESHAM Rewrite on first episode of new series for Sly Fox/ITV. …………………………………………………………………………………………. REVENGE.COM Script for original series for Kindle Entertainment. COLD FEET IX Episode two for Big Talk/ITV. TX January 2020. THE TROUBLE WITH MAGGIE COLE Written all six episodes of original series for Genial Productions/ITV. Dawn French in title role as Maggie Cole – TX March 2020. COLD FEET VIII Episode three, hailed by viewers as “the best ever episode” following TX on 28th January 2019. Big Talk/ITV. MEET THE CROWS Pitch delivered to ITV Studios. PATIO Treatment delivered to Company Pictures. BYRON Original series treatment delivered to Balloon Entertainment. MOUNT PLEASANT FINALE Wrote the final episode of Mount Pleasant for Tiger Aspect/Sky Living. TX 30th June 2017. BENIDORM X Wrote 4 episodes of new series for Tiger Aspect/ITV. MOUNT PLEASANT VI Wrote 9 of the 10 episodes for series six having been sole writer on the fifth series, Lead Writer on the fourth series, written half of the third series, and 5 of 10 episodes of the second for Tiger Aspect/Sky Living. BENIDORM IX Wrote an episode of Benidorm for Tiger Aspect/ITV. DEATH IN PARADISE IV Completed an episode of series four for Red Planet/BBC1. THE WORST YEAR OF MY LIFE… AGAIN Wrote six half-hour episodes for his original series developed with CBBC/ACTF/ABC, TX May 2014. -

Reflections on Rome Exploring Duquesne's Connections to Italy

FALL 2018 Reflections on Rome Exploring Duquesne's Connections to Italy Also in this issue: A Decade in the Dominican Republic Rooney Symposiumwww.duq.edu Recap 1 DUQUESNE UNIVERSITY MAGAZINE Contents An Inspirational Morning 36 with Pope Francis A Decade in the Biden, Former Steelers 6 Dominican Republic 12 Honor Dan Rooney Every Issue Also... Did You Know?.......................................11 DU in Pictures ......................................32 20 23 Creating Knowledge .........................58 Engaging to Make Duquesne to Host Bluff in Brief ...........................................60 a Difference National Experts at First Athletics ..................................................62 Duquesne University’s new Office Amendment Symposium Alumni Updates ..................................67 of Community Engagement University to hold two-day event to Event Calendar .................................... 72 connects the University and discuss the history and current-day community resources. impact of this bedrock of American freedom. Facebook “f” Logo CMYK / .eps Facebook “f” Logo CMYK / .eps Vol. 17, Number 1, Fall ’18. Duquesne University Magazine is published by the Office of Marketing and Communications, 406 Koren Building, 600 Forbes Ave., Pittsburgh, PA 15282, Tel: 412.396.6050, Fax: 412.396.5779, Email: [email protected] 2 DUQUESNE UNIVERSITY MAGAZINE Fall '18 PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE Thoughts from the President ince its creation, Duquesne University’s character has been international in scope. The University’s founding Spiritans were Sfrom Europe. Its earliest mission was to help the children of immigrant families. So, 140 years later, it’s fitting that the University continues to focus on international ties. This issue’s cover story celebrates Duquesne’s links to Rome, home of the University’s Italian campus, headquarters of the Spiritans and center of the Roman Catholic Church. -

Do Palácio De Cristal Portuense Ao Pavilhão Rosa Mota Volume I Vera Lúcia Da Silva Braga Penetra Gonçalves

MESTRADO HISTÓRIA DA ARTE, PATRIMÓNIO E CULTURA VISUAL Imagens e Memórias em Reconstrução: Do Palácio de Cristal Portuense ao Pavilhão Rosa Mota Volume I Vera Lúcia da Silva Braga Penetra Gonçalves M 2018 Vera Lúcia da Silva Braga Penetra Gonçalves Imagens e Memórias em Reconstrução: Do Palácio de Cristal Portuense ao Pavilhão Rosa Mota Volume I Dissertação realizada no âmbito do Mestrado em História da Arte, Património e Cultura Visual, orientada pelo Professor Doutor Hugo Daniel da Silva Barreira e coorientada pela Professora Doutora Maria Manuela Gomes de Azevedo Pinto Faculdade de Letras da Universidade do Porto setembro de 2018 Imagens e Memórias em Reconstrução: Do Palácio de Cristal Portuense ao Pavilhão Rosa Mota Volume I Vera Lúcia da Silva Braga Penetra Gonçalves Dissertação realizada no âmbito do Mestrado em História da Arte, Património e Cultura Visual, orientada pelo Professor Doutor Hugo Daniel da Silva Barreira e coorientada pela Professora Doutora Maria Manuel Gomes de Azevedo Pinto Membros do Júri Professor Doutor Manuel Joaquim Moreira da Rocha Faculdade de Letras - Universidade do Porto Professora Doutora Teresa Dulce Portela Marques Faculdade de Ciências – Universidade Universidade do Porto Professor Doutor Hugo Daniel da Silva Barreira Faculdade de Letras - Universidade do Porto Classificação obtida: 20 valores À memória do meu pai Sumário Declaração de honra .................................................................................................................. 9 Agradecimentos .......................................................................................................................... -

Medalhas Atribuidas Até Ao 25 Abril 1974

MEDALHAS ATRIBUIDAS ATÉ AO 25 ABRIL 1974 Atribuição Nome Título Medalha Tipo Observações Entrega Acácio Lima responsável pelos painéis da capela-mor da Igreja dos Congregados. 07/11/1942 Acácio Lima Arquitecto Mérito Ouro Arquitecto modernista, com obra relevante na cidade. Fez parte da Organização dos 07/11/1942 Arquitectos Modernos (ODAM), que existiu de 1947 a 1952. Empenhou-se em prol da construção do Teatro Municipal do Porto - Rivoli ficando 09/08/1948 Maria Fernandes Borges D. Mérito Ouro 09/08/1948 associada a um dos mais importantes espaços culturais do Porto. Médico e militar português, diretor do Hospital Militar Regional n.º 1 (D. Pedro V) do 10/03/1950 Augusto de Sousa Rosa Tenente-Coronel Honra Ouro 10/03/1950 Porto e Presidente da Comissão Administrativa da Câmara Municipal do Porto. Médico, professor de Medicina, publicista e político republicano com actividade no período da Primeira República Portuguesa e do Estado Novo. Foi Reitor 10/03/1950 José Alfredo Mendes de Magalhães Prof. Doutor Honra Ouro da Universidade do Porto, Procurador à Câmara Corporativa, Ministro da Instrução 10/03/1950 Pública, Governador-Geral de Moçambique e Presidente da Câmara Municipal do Porto. Presidente da Comissão Administrativa da Câmara Municipal do Porto, no final da década de 1920. Comendador da Ordem de Avis, em 28 de Junho de 1919, 10/03/1950 Raul de Andrade Peres Coronel Honra Ouro 10/03/1950 Comendador da Ordem Militar da Torre e Espada, do Valor, Lealdade e Mérito, em 5 de Outubro de 1919 e Grande Oficial da Ordem de Avis, em 5 de outubro de 1928. -

Cultural Landscape of the Alto Douro Wine Region Archaeological Sites

Historic Centre of Porto The history of Porto, which is proudly known as the Cidade Association), the Ferreira Borges Market and the building known as the Alfândega Nova (New Customs Invicta (Invencible City) is profoundly linked to the River Douro, that hard to navigate river House), at the entrance to Miragaia, clearly attest to this. which curves and proudly displays its six bridges, inviting observation… of the D. Luís bridge, At the end of the middle ages, the city began to spread beyond the upper town - the Episcopal city - and the lower a cast iron structure in the 19th century style, whose higher and lower levels link the banks mercantile and trading town. From the beginning of the 14th century, the hillside once known as Olival, nowa- of the cities of Porto and Vila Nova de Gaia. Both have a history and stories to tell, both banks days named Vitória, saw a new urban dynamism, thanks to the creation of the New Jewish Quarter, in the street invite us to stop a while. where the São Bento da Vitória Monastery would eventually be built. In the 18th century the Clérigos Church, with its house and tower, paid homage to the Christian faith with its art, setting its stamp on the personality of Leaving the Monastery of Santo Agostinho da Serra do Pilar, through the top level of the bridge, we soon the place and becoming the trademark of the city. This masterpiece of baroque architecture was designed by the arrive at Porto Cathedral, the symbol of what was once the Episcopal city.