Platelet Aggregation Inhibitors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

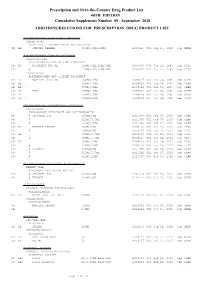

Additions and Deletions to the Drug Product List

Prescription and Over-the-Counter Drug Product List 40TH EDITION Cumulative Supplement Number 09 : September 2020 ADDITIONS/DELETIONS FOR PRESCRIPTION DRUG PRODUCT LIST ACETAMINOPHEN; BUTALBITAL; CAFFEINE TABLET;ORAL BUTALBITAL, ACETAMINOPHEN AND CAFFEINE >A> AA STRIDES PHARMA 325MG;50MG;40MG A 203647 001 Sep 21, 2020 Sep NEWA ACETAMINOPHEN; CODEINE PHOSPHATE SOLUTION;ORAL ACETAMINOPHEN AND CODEINE PHOSPHATE >D> AA WOCKHARDT BIO AG 120MG/5ML;12MG/5ML A 087006 001 Jul 22, 1981 Sep DISC >A> @ 120MG/5ML;12MG/5ML A 087006 001 Jul 22, 1981 Sep DISC TABLET;ORAL ACETAMINOPHEN AND CODEINE PHOSPHATE >A> AA NOSTRUM LABS INC 300MG;15MG A 088627 001 Mar 06, 1985 Sep CAHN >A> AA 300MG;30MG A 088628 001 Mar 06, 1985 Sep CAHN >A> AA ! 300MG;60MG A 088629 001 Mar 06, 1985 Sep CAHN >D> AA TEVA 300MG;15MG A 088627 001 Mar 06, 1985 Sep CAHN >D> AA 300MG;30MG A 088628 001 Mar 06, 1985 Sep CAHN >D> AA ! 300MG;60MG A 088629 001 Mar 06, 1985 Sep CAHN ACETAMINOPHEN; HYDROCODONE BITARTRATE TABLET;ORAL HYDROCODONE BITARTRATE AND ACETAMINOPHEN >A> @ CEROVENE INC 325MG;5MG A 211690 001 Feb 07, 2020 Sep CAHN >A> @ 325MG;7.5MG A 211690 002 Feb 07, 2020 Sep CAHN >A> @ 325MG;10MG A 211690 003 Feb 07, 2020 Sep CAHN >D> AA VINTAGE PHARMS 300MG;5MG A 090415 001 Jan 24, 2011 Sep DISC >A> @ 300MG;5MG A 090415 001 Jan 24, 2011 Sep DISC >D> AA 300MG;7.5MG A 090415 002 Jan 24, 2011 Sep DISC >A> @ 300MG;7.5MG A 090415 002 Jan 24, 2011 Sep DISC >D> AA 300MG;10MG A 090415 003 Jan 24, 2011 Sep DISC >A> @ 300MG;10MG A 090415 003 Jan 24, 2011 Sep DISC >D> @ XIROMED 325MG;5MG A 211690 -

Health Reports for Mutual Recognition of Medical Prescriptions: State of Play

The information and views set out in this report are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of the European Union. Neither the European Union institutions and bodies nor any person acting on their behalf may be held responsible for the use which may be made of the information contained therein. Executive Agency for Health and Consumers Health Reports for Mutual Recognition of Medical Prescriptions: State of Play 24 January 2012 Final Report Health Reports for Mutual Recognition of Medical Prescriptions: State of Play Acknowledgements Matrix Insight Ltd would like to thank everyone who has contributed to this research. We are especially grateful to the following institutions for their support throughout the study: the Pharmaceutical Group of the European Union (PGEU) including their national member associations in Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, the Netherlands, Poland and the United Kingdom; the European Medical Association (EMANET); the Observatoire Social Européen (OSE); and The Netherlands Institute for Health Service Research (NIVEL). For questions about the report, please contact Dr Gabriele Birnberg ([email protected] ). Matrix Insight | 24 January 2012 2 Health Reports for Mutual Recognition of Medical Prescriptions: State of Play Executive Summary This study has been carried out in the context of Directive 2011/24/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 9 March 2011 on the application of patients’ rights in cross- border healthcare (CBHC). The CBHC Directive stipulates that the European Commission shall adopt measures to facilitate the recognition of prescriptions issued in another Member State (Article 11). At the time of submission of this report, the European Commission was preparing an impact assessment with regards to these measures, designed to help implement Article 11. -

A Comparative Study of Molecular Structure, Pka, Lipophilicity, Solubility, Absorption and Polar Surface Area of Some Antiplatelet Drugs

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Article A Comparative Study of Molecular Structure, pKa, Lipophilicity, Solubility, Absorption and Polar Surface Area of Some Antiplatelet Drugs Milan Remko 1,*, Anna Remková 2 and Ria Broer 3 1 Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry, Faculty of Pharmacy, Comenius University in Bratislava, Odbojarov 10, SK-832 32 Bratislava, Slovakia 2 Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Slovak Medical University, Limbová 12, SK–833 03 Bratislava, Slovakia; [email protected] 3 Department of Theoretical Chemistry, Zernike Institute for Advanced Materials, University of Groningen, Nijenborgh 4, 9747 AG Groningen, The Netherlands; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +421-2-5011-7291 Academic Editor: Michael Henein Received: 18 February 2016; Accepted: 11 March 2016; Published: 19 March 2016 Abstract: Theoretical chemistry methods have been used to study the molecular properties of antiplatelet agents (ticlopidine, clopidogrel, prasugrel, elinogrel, ticagrelor and cangrelor) and several thiol-containing active metabolites. The geometries and energies of most stable conformers of these drugs have been computed at the Becke3LYP/6-311++G(d,p) level of density functional theory. Computed dissociation constants show that the active metabolites of prodrugs (ticlopidine, clopidogrel and prasugrel) and drugs elinogrel and cangrelor are completely ionized at pH 7.4. Both ticagrelor and its active metabolite are present at pH = 7.4 in neutral undissociated form. The thienopyridine prodrugs ticlopidine, clopidogrel and prasugrel are lipophilic and insoluble in water. Their lipophilicity is very high (about 2.5–3.5 logP values). The polar surface area, with regard to the structurally-heterogeneous character of these antiplatelet drugs, is from very large interval of values of 3–255 Å2. -

Cilostazol Protects Rats Against Alcohol‑Induced Hepatic Fibrosis Via Suppression of TGF‑Β1/CTGF Activation and the Camp/Epac1 Pathway

EXPERIMENTAL AND THERAPEUTIC MEDICINE 17: 2381-2388, 2019 Cilostazol protects rats against alcohol‑induced hepatic fibrosis via suppression of TGF‑β1/CTGF activation and the cAMP/Epac1 pathway KUN HAN, YANTING ZHANG and ZHENWEI YANG Department of Gastroenterology, Xi'an Central Hospital, Xi'an, Shaanxi 710003, P.R. China Received July 2, 2018; Accepted November 23, 2018 DOI: 10.3892/etm.2019.7207 Abstract. Alcohol abuse and chronic alcohol consump- Introduction tion are major causes of alcoholic liver disease worldwide, particularly alcohol‑induced hepatic fibrosis (AHF). Liver Liver fibrosis is a wound‑healing response to a variety of liver fibrosis is an important public health concern because of its insults, including excessive alcohol intake. Alcohol abuse and high morbidity and mortality. The present study examined chronic alcohol consumption are major causes of alcoholic the mechanisms and effects of the phosphodiesterase III liver disease (ALD) worldwide (1). Alcohol‑induced hepatic inhibitor cilostazol on AHF. Rats received alcohol infu- fibrosis (AHF) may cause serious hepatic cirrhosis, and is sions via gavage to induce liver fibrosis and were treated widely accepted as a milestone event in ALD (2). However, with colchicine (positive control) or cilostazol. The serum recent evidence indicates that liver fibrosis is reversible and alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) and acetaldehyde dehydro- that the liver may recover from cirrhosis (3). Therefore, eluci- genase (ALDH) activities and the albumin/globulin (A/G), dation of the cellular and molecular mechanisms is urgently enzymes and hyaluronic acid (HA), type III precollagen required to prevent AHF. (PC III), laminin (LA), and type IV collagen (IV‑C) levels The exact mechanism remains unclear, but certain changes were measured using commercially available kits. -

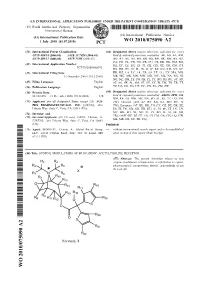

Wo 2010/075090 A2

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date 1 July 2010 (01.07.2010) WO 2010/075090 A2 (51) International Patent Classification: (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every C07D 409/14 (2006.01) A61K 31/7028 (2006.01) kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, C07D 409/12 (2006.01) A61P 11/06 (2006.01) AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BR, BW, BY, BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, DO, (21) International Application Number: DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, PCT/US2009/068073 HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IS, JP, KE, KG, KM, KN, KP, (22) International Filing Date: KR, KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LT, LU, LY, MA, MD, 15 December 2009 (15.12.2009) ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, OM, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, RO, RS, RU, SC, SD, (25) Filing Language: English SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TJ, TM, TN, TR, TT, (26) Publication Language: English TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. (30) Priority Data: (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every 61/122,478 15 December 2008 (15.12.2008) US kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, GM, KE, LS, MW, MZ, NA, SD, SL, SZ, TZ, UG, ZM, (71) Applicant (for all designated States except US): AUS- ZW), Eurasian (AM, AZ, BY, KG, KZ, MD, RU, TJ, PEX PHARMACEUTICALS, INC. -

PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX to the TARIFF SCHEDULE 2 Table 1

Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States (2020) Revision 19 Annotated for Statistical Reporting Purposes PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE HARMONIZED TARIFF SCHEDULE Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States (2020) Revision 19 Annotated for Statistical Reporting Purposes PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE TARIFF SCHEDULE 2 Table 1. This table enumerates products described by International Non-proprietary Names INN which shall be entered free of duty under general note 13 to the tariff schedule. The Chemical Abstracts Service CAS registry numbers also set forth in this table are included to assist in the identification of the products concerned. For purposes of the tariff schedule, any references to a product enumerated in this table includes such product by whatever name known. -

Health and Social Outcomes Associated with High-Risk Alcohol Use

Manitoba Centre for Health Policy Health and Social Outcomes Associated with High-Risk Alcohol Use Summer 2018 Nathan C Nickel, MPH, PhD Jeff Valdivia, MNRM, CAPM Deepa Singal, PhD James Bolton, MD Christine Leong, PharmD Susan Burchill, BMus Leonard MacWilliam, MSc, MNRM Geoffrey Konrad, MD Randy Walld, BSc, BComm (Hons) Okechukwu Ekuma, MSc Greg Finlayson, PhD Leanne Rajotte, BComm (Hons) Heather Prior, MSc Josh Nepon, MD Michael Paille, BHSc This report is produced and published by the Manitoba Centre for Health Policy (MCHP). It is also available in PDF format on our website at: http://mchp-appserv.cpe.umanitoba.ca/deliverablesList.html Information concerning this report or any other report produced by MCHP can be obtained by contacting: Manitoba Centre for Health Policy Rady Faculty of Health Sciences Max Rady College of Medicine, University of Manitoba 4th Floor, Room 408 727 McDermot Avenue Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada R3E 3P5 Email: [email protected] Phone: (204) 789-3819 Fax: (204) 789-3910 How to cite this report: Nathan C Nickel, James Bolton, Leonard MacWilliam, Okechukwu Ekuma, Heather Prior, Jeff Valdivia, Christine Leong, Geoffrey Konrad, Greg Finlayson, Josh Nepon, Deepa Singal, Susan Burchill, Randy Walld, Leanne Rajotte, Michael Paille. Health and Social Outcomes Associated with High-Risk Alcohol Use. Winnipeg, MB. Manitoba Centre for Health Policy, Summer 2018. Legal Deposit: Manitoba Legislative Library National Library of Canada ISBN 978-1-896489-90-2 ©Manitoba Health This report may be reproduced, in whole or in part, provided the source is cited. 1st printing (Summer 2018) This report was prepared at the request of Manitoba Health, Seniors and Active Living (MHSAL), a department within the Government of Manitoba, as part of the contract between the University of Manitoba and MHSAL. -

The Delivery Strategy of Paclitaxel Nanostructured Lipid Carrier Coated with Platelet Membrane

cancers Article The Delivery Strategy of Paclitaxel Nanostructured Lipid Carrier Coated with Platelet Membrane 1, 1, 1 2 3 Ki-Hyun Bang y, Young-Guk Na y , Hyun Wook Huh , Sung-Joo Hwang , Min-Soo Kim , Minki Kim 1, Hong-Ki Lee 1,* and Cheong-Weon Cho 1,* 1 College of Pharmacy, Chungnam National University, Daejeon 34134, Korea; [email protected] (K.-H.B.); [email protected] (Y.-G.N.); [email protected] (H.W.H.); [email protected] (M.K.) 2 College of Pharmacy and Yonsei Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Yonsei University, 162-1 Songdo-dong, Yeonsu-gu, Incheon 406-840, Korea; [email protected] 3 College of Pharmacy, Pusan National University, 63 Busandaehak-ro, Geumjeong-gu, Busan 609-735, Korea; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (H.-K.L.); [email protected] (C.-W.C.); Tel.: +82-42-821-5934 (H.-K.L. & C.-W.C.); Fax: +82-42-823-6566 (H.-K.L. & C.-W.C.) These authors contributed equally. y Received: 2 May 2019; Accepted: 10 June 2019; Published: 11 June 2019 Abstract: Strategies for the development of anticancer drug delivery systems have undergone a dramatic transformation in the last few decades. Lipid-based drug delivery systems, such as a nanostructured lipid carrier (NLC), are one of the systems emerging to improve the outcomes of tumor treatments. However, NLC can act as an intruder and cause an immune response. To overcome this limitation, biomimicry technology was introduced to decorate the surface of the nanoparticles with various cell membrane proteins. Here, we designed paclitaxel (PT)-loaded nanostructured lipid carrier (PT-NLC) with platelet (PLT) membrane protein because PLT is involved with angiogenesis and interaction of circulating tumor cells. -

Cilostazol Tablets, USP50 Mg and 100 Mgrx Only

CILOSTAZOL - cilostazol tablet Physicians Total Care, Inc. ---------- Cilostazol Tablets, USP 50 mg and 100 mg Rx only CONTRAINDICATION Cilostazol and several of its metabolites are inhibitors of phosphodiesterase III. Several drugs with this pharmacologic effect have caused decreased survival compared to placebo in patients with class III-IV congestive heart failure. Cilostazol is contraindicated in patients with congestive heart failure of any severity. DESCRIPTION Cilostazol is a quinolinone derivative that inhibits cellular phosphodiesterase (more specific for phosphodiesterase III). The empirical formula of cilostazol is C20H27N5O2, and its molecular weight is 369.46. Cilostazol is 6-[4-(1-cyclohexyl-1H-tetrazol-5-yl)butoxy]-3,4-dihydro-2(1H)-quinolinone, CAS-73963-72-1. The structural formula is: Cilostazol occurs as white to off-white crystals or as a crystalline powder that is slightly soluble in methanol and ethanol, and is practically insoluble in water, 0.1 N HCl, and 0.1 N NaOH. Cilostazol Tablets, USP for oral administration are available as 50 mg or 100 mg round, white debossed tablets. Each tablet, in addition to the active ingredient, contains the following inactive ingredients: carboxymethylcellulose calcium, corn starch, hypromellose, magnesium stearate and microcrystalline cellulose. CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY Mechanism of Action The mechanism of the effects of Cilostazol Tablets, USP on the symptoms of intermittent claudication is not fully understood. Cilostazol Tablets, USP and several of its metabolities are cyclic AMP (cAMP) phosphodiesterase III inhibitors (PDE III inhibitors), inhibiting phosphodiesterase activity and suppressing cAMP degration with a resultant increase in cAMP in platelets and blood vessels, leading to inhibition of platelet aggregation and vasodilation, respectively. -

Guideline for Preoperative Medication Management

Guideline: Preoperative Medication Management Guideline for Preoperative Medication Management Purpose of Guideline: To provide guidance to physicians, advanced practice providers (APPs), pharmacists, and nurses regarding medication management in the preoperative setting. Background: Appropriate perioperative medication management is essential to ensure positive surgical outcomes and prevent medication misadventures.1 Results from a prospective analysis of 1,025 patients admitted to a general surgical unit concluded that patients on at least one medication for a chronic disease are 2.7 times more likely to experience surgical complications compared with those not taking any medications. As the aging population requires more medication use and the availability of various nonprescription medications continues to increase, so does the risk of polypharmacy and the need for perioperative medication guidance.2 There are no well-designed trials to support evidence-based recommendations for perioperative medication management; however, general principles and best practice approaches are available. General considerations for perioperative medication management include a thorough medication history, understanding of the medication pharmacokinetics and potential for withdrawal symptoms, understanding the risks associated with the surgical procedure and the risks of medication discontinuation based on the intended indication. Clinical judgement must be exercised, especially if medication pharmacokinetics are not predictable or there are significant risks associated with inappropriate medication withdrawal (eg, tolerance) or continuation (eg, postsurgical infection).2 Clinical Assessment: Prior to instructing the patient on preoperative medication management, completion of a thorough medication history is recommended – including all information on prescription medications, over-the-counter medications, “as needed” medications, vitamins, supplements, and herbal medications. Allergies should also be verified and documented. -

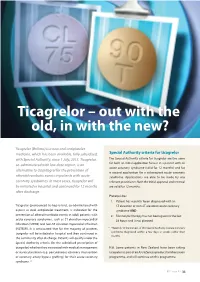

Ticagrelor – out with the Old, in with the New?

Ticagrelor – out with the old, in with the new? Ticagrelor (Brilinta) is a new oral antiplatelet medicine, which has been available, fully subsidised, Special Authority criteria for ticagrelor with Special Authority, since 1 July, 2013. Ticagrelor, The Special Authority criteria for ticagrelor are the same co-administered with low dose aspirin, is an for both an initial application for use in a patient with an acute coronary syndrome (valid for 12 months) and for alternative to clopidogrel for the prevention of a second application for a subsequent acute coronary atherothrombotic events in patients with acute syndrome. Applications are able to be made by any coronary syndromes. In most cases, ticagrelor will relevant practitioner. Both the initial approval and renewal be initiated in hospital and continued for 12 months are valid for 12 months. after discharge. Prerequisites: 1. Patient has recently* been diagnosed with an Ticagrelor (pronounced tie-kag-re-lore), co-administered with ST elevation or non-ST elevation acute coronary aspirin as dual antiplatelet treatment, is indicated for the syndrome AND prevention of atherothrombotic events in adult patients with 2. Fibrinolytic therapy has not been given in the last acute coronary syndromes, such as ST elevation myocardial 24 hours and is not planned infarction (STEMI) and non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI). It is anticipated that for the majority of patients, * “Recently” in the context of this Special Authority is acute coronary ticagrelor will be initiated in hospital and then continued in syndrome diagnosed within a few days or weeks rather than months. the community after discharge. Patients will qualify under the Special Authority criteria (for the subsidised prescription of ticagrelor) whether they are treated with medical management N.B. -

Pharmacokinetic Characteristics of Cilostazol 200 Mg Controlled

2016;24(4):183-188 TCP Transl Clin Pharmacol http://dx.doi.org/10.12793/tcp.2016.24.4.183 Pharmacokinetic characteristics of cilostazol 200 mg controlled-release tablet compared with two cilostazol 100 mg immediate-release tablets (Pletal) after single oral dose in healthy Korean male volunteers ORIGINAL ARTICLE Jin Dong Son1,4, Sang Min Cho2, Youn Woong Choi2, Soo-Hwan Kim3, In Sun Kwon4, Eun-Heui Jin4, Jae Woo Kim4 and Jang Hee Hong1,4,5* 1Department of Medical Science, College of Medicine, Chungnam National University, Daejeon 35015, republic of Korea, 2Korea Unit- ed Pharm.Inc., Seoul 06116, Republic of Korea, 3Caleb Multilab Inc., Seoul 06745, Republic of Korea, 4Clinical Trials Center, Chun- gnam National University Hospital, Daejeon 35015, South Korea, 5Department of Pharmacology, College of Medicine, Chungnam National University, Daejeon 35015, Republic of Korea *Correspondence: J.H. Hong; Tel: +82-42-280-6940, Fax: +82-42-280-6940, E-mail: [email protected] Received 8 Sep 2016 Cilostazol controlled-release (CR) tablets have recently been developed by Korea United Pharm Revised 28 Nov 2016 (Seoul, Korea). The tablets use a patented double CR system, which improves drug compliance by Accepted 29 Nov 2016 allowing “once daily” administration and reduces adverse events by sustaining a more even plasma Keywords concentration for 24 h. We conducted an open, randomized, two-period, two-treatment, cross- Cilostazol, OPC-13015, over study to compare the pharmacokinetic (PK) characteristics and tolerability of cilostazol when OPC-13213, administered to healthy Korean male volunteers as CR or immediate release (IR) tablets (Pletal, bioequivalence, Korea Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Gyeonggi-do, Korea).