CERC: Terrorism and Bioterrorism Communication Challenges

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pathogens As Weapons Gregory Koblentz the International Security Implications of Biological Warfare

Pathogens as Weapons Pathogens as Weapons Gregory Koblentz The International Security Implications of Biological Warfare Biological weapons have become one of the key security issues of the twenty-ªrst century.1 Three factors that ªrst emerged in the 1990s have contributed to this phenomenon. First, revelations regarding the size, scope, and sophistication of the Soviet and Iraqi biological warfare programs focused renewed attention on the prolifera- tion of these weapons.2 Second, the catastrophic terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, and the anthrax letters sent to media outlets and Senate ofªces in the United States during the following month, demonstrated the desire of terror- ists to cause massive casualties and heightened concern over their ability to employ biological weapons.3 Third, signiªcant advances in the life sciences have increased concerns about how the biotechnology revolution could be ex- ploited to develop new or improved biological weapons.4 These trends suggest that there is a greater need than ever to answer several fundamental questions about biological warfare: What is the nature of the threat? What are the poten- tial strategic consequences of the proliferation of biological weapons? How ef- Gregory Koblentz is a doctoral candidate in Political Science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. I would like to thank Robert Art, Thomas Christensen, Linda Fu, Jeanne Guillemin, Kendall Hoyt, Milton Leitenberg, John Ellis van Courtland Moon, Julian Perry Robinson, Harvey Sapolsky, Mar- garet Sloane, Jonathan Tucker, and Stephen Van Evera for their support and discussion of previous drafts. I am also grateful for comments from the participants in seminars at the Massachusetts In- stitute of Technology’s Security Studies Program, Harvard University’s John M. -

Mitchell & Kilner

THE NEWSLETTER VOLUME 9 OF THE CENTER NUMBER 3 FOR BIOETHICS AND SUMMER 2003 HUMAN DIGNITY Inside: Remaking Humans: The New Utopians Versus a Truly Human Future1 Remaking Humans: The New Utopians Versus a Truly Human C. Ben Mitchell, Ph.D., Senior FeIIow,The Center for Bioethics and Human Dignity 1 John F. Kilner, Ph.D., President,The Center for Bioethics and Human Dignity Future If the nineteenth century was the age of the mentally by making use of reason, science, The Genetics of Mice and Men: machine and the twentieth century the infor and technology. In addition, respect for the Can—and Should—We mation age, this century is, by most accounts, rights of the individual and a belief in the 2 the age of biotechnology. In this biotech cen power of human ingenuity are important ele Intervene? tury we may witness the invention of cures for ments of transhumanism. Transhumanists genetically linked diseases, including also repudiate belief in the existence of super Movie Review natural powers that guide us. These things 4 Alzheimer’s, cancer, and a host of maladies News from the Field that cause tremendous human suffering. We together represent the core of our philosophy. may see amazing developments in food pro The critical and rational approach which duction with genetically modified foods that transhumanists support is at the service of the 6 Book Review actually carry therapeutic drugs inside them. desire to improve humankind and humanity in all their facets.” Bioterrorism and high-tech weaponry may 7 Center Resources also be in our future. Some researchers are even suggesting that our future might include Again, the idea of improving society through the remaking of the human species. -

Agroterrorism: Threats and Preparedness

Order Code RL32521 Agroterrorism: Threats and Preparedness Updated March 12, 2007 Jim Monke Analyst in Agricultural Policy Resources, Science, and Industry Division Agroterrorism: Threats and Preparedness Summary The potential for terrorist attacks against agricultural targets (agroterrorism) is increasingly recognized as a national security threat, especially after the events of September 11, 2001. Agroterrorism is a subset of bioterrorism, and is defined as the deliberate introduction of an animal or plant disease with the goal of generating fear, causing economic losses, and/or undermining social stability. The goal of agroterrorism is not to kill cows or plants. These are the means to the end of causing economic damage, social unrest, and loss of confidence in government. Human health could be at risk if contaminated food reaches the table or if an animal pathogen is transmissible to humans (zoonotic). While agriculture may not be a terrorist’s first choice because it lacks the “shock factor” of more traditional terrorist targets, many analysts consider it a viable secondary target. Agriculture has several characteristics that pose unique vulnerabilities. Farms are geographically disbursed in unsecured environments. Livestock are frequently concentrated in confined locations, and transported or commingled with other herds. Many agricultural diseases can be obtained, handled, and distributed easily. International trade in food products often is tied to disease-free status, which could be jeopardized by an attack. Many veterinarians lack experience with foreign animal diseases that are eradicated domestically but remain endemic in foreign countries. In the past five years, “food defense” has received increasing attention in the counterterrorism and bioterrorism communities. Laboratory and response capacity are being upgraded to address the reality of agroterrorism, and national response plans now incorporate agroterrorism. -

Bioterrorism, Biological Weapons and Anthrax

Bioterrorism, Biological Weapons and Anthrax Part IV Written by Arthur H. Garrison Criminal Justice Planning Coordinator Delaware Criminal Justice Council Bioterrorism and biological weapons The use of bio-terrorism and bio-warfare dates back to 6th century when the Assyrians poisoned the well water of their enemies. The goal of using biological weapons is to cause massive sickness or death in the intended target. Bioterrorism and biological weapons The U.S. took the threat of biological weapons attack seriously after Gulf War. Anthrax vaccinations of U.S. troops Investigating Iraq and its biological weapons capacity The Soviet Union manufactured various types of biological weapons during the 1980’s • To be used after a nuclear exchange • Manufacturing new biological weapons – Gene engineering – creating new types of viruses/bacteria • Contagious viruses – Ebola, Marburg (Filoviruses) - Hemorrhagic fever diseases (vascular system dissolves) – Smallpox The spread of biological weapons after the fall of the Soviet Union •Material • Knowledge and expertise •Equipment Bioterrorism and biological weapons There are two basic categories of biological warfare agents. Microorganisms • living organic germs, such as anthrax (bacillus anthrax). –Bacteria –Viruses Toxins • By-products of living organisms (natural poisons) such as botulism (botulinum toxin) which is a by- product of growing the microorganism clostridium botulinum Bioterrorism and biological weapons The U.S. was a leader in the early research on biological weapons Research on making -

Agricultural Bioterrorism

From the pages of Recent titles Agricultural Bioterrorism: A Federal Strategy to Meet the Threat Agricultural in the McNair MCNAIR PAPER 65 Bioterrorism: Paper series: A Federal Strategy to Meet the Threat 64 The United States ignores the The Strategic Implications of a Nuclear-Armed Iran Agricultural potential for agricultural bioter- Kori N. Schake and rorism at its peril. The relative Judith S. Yaphe Bioterrorism: ease of a catastrophic bio- weapons attack against the 63 A Federal Strategy American food and agriculture All Possible Wars? infrastructure, and the devastat- Toward a Consensus View of the Future Security to Meet the Threat ing economic and social conse- Environment, 2001–2025 quences of such an act, demand Sam J. Tangredi that the Nation pursue an aggres- sive, focused, coordinated, and 62 stand-alone national strategy to The Revenge of the Melians: Asymmetric combat agricultural bioterrorism. Threats and the Next QDR The strategy should build on Kenneth F. McKenzie, Jr. counterterrorism initiatives already underway; leverage exist- 61 ing Federal, state, and local pro- Illuminating HENRY S. PARKER grams and capabilities; and Tomorrow’s War Martin C. Libicki involve key customers, stake- PARKER holders, and partners. The U.S. 60 Department of Agriculture The Revolution in should lead the development of Military Affairs: this strategy. Allied Perspectives Robbin F. Laird and Holger H. Mey Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University About the Author NATIONAL DEFENSE UNIVERSITY President: Vice Admiral Paul G. Gaffney II, USN Henry S. Parker is National Program Leader for Aquaculture at the Vice President: Ambassador Robin Lynn Raphel Agricultural Research Service in the U.S. -

Efficient Responses to Catastrophic Risk Richard A

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 2006 Efficient Responseso t Catastrophic Risk Richard A. Posner Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/journal_articles Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Richard A. Posner, "Efficient Responseso t Catastrophic Risk," 6 Chicago Journal of International Law 511 (2006). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Efficient Responses to Catastrophic Risk Richard A. Posner* The Indian Ocean tsunami of December 2004 has focused attention on a type of disaster to which policymakers pay too little attention-a disaster that has a very low or unknown probability of occurring but that if it does occur creates enormous losses. Great as the death toll, physical and emotional suffering of survivors, and property damage caused by the tsunami were, even greater losses could be inflicted by other disasters of low (but not negligible) or unknown probability. The asteroid that exploded above Siberia in 1908 with the force of a hydrogen bomb might have killed millions of people had it exploded above a major city. Yet that asteroid was only about two hundred feet in diameter, and a much larger one (among the thousands of dangerously large asteroids in orbits that intersect the earth's orbit) could strike the earth and cause the total extinction of the human race through a combination of shock waves, fire, tsunamis, and blockage of sunlight wherever it struck. -

Singularity Warfare: a Bibliometric Survey of Militarized Transhumanism

A peer-reviewed electronic journal published by the Institute for Ethics and Emerging Technologies ISSN 1541-0099 16(1) – June 2007 Singularity Warfare: A Bibliometric Survey of Militarized Transhumanism Woody Evans Tarrant County College ([email protected] ) http://jetpress.org/v16/evans.html Abstract This paper examines a number of terms related to transhumanism, and their prevalence in military and government publications. Transhumanism and the technologies attendant to the movement have clear implications for militaries and insurgencies. Although strategists in all camps must begin to plan for the possible impacts of such technologies if they wish to stay relevant and ready on a global scale, the impact of transhuman values is all but nonexistent in the military literature. This paper concludes that the lack of transhuman terms in military journals illustrates an ignorance of transhumanism amongst military thinkers and policy makers. 1. Introduction Transhumanism, the philosophical movement which employs advanced technologies to further rational humanism (Bostrom, 2005, 2), has something to say about many fields of human inquiry and activity, including medicine, information science, sociology, and, even military science. In the United States, spending on military and defense is very large – over $400 billion dollars in 2005 (Office of Management and Budget, 2006). Indeed, research and development funds for defense have been increased by over 50% since 2001 (OMB, 2006). The connection between technology and the military is clear; the relationship between transhuman terms and military science may reveal, more broadly, the military’s attitude toward transhuman thought. As we shall show, transhumanism does not strongly impact military or defense literature. -

Preparing for and Responding to Bioterrorism Information for the Public Health Workforce

Instructor’s Manual 1 Preparing for and Responding to Bioterrorism Information for the Public Health Workforce Introduction to Bioterrorism Developed by Jennifer Brennan Braden, MD, MPH Preparing for and Responding to Bioterrorism: Information for the Public Health Workforce Introduction to Bioterrorism Developed by Jennifer Brennan Braden, MD, MPH Northwest Center for Public Health Practice University of Washington Seattle, Washington *This manual and the accompanying MS Powerpoint slides are current as of December 2002. Please refer to http://nwcphp.org/bttrain/ for updates to the material. Last Revised December 2002 Acknowledgements This manual and the accompanying MS PowerPoint slides were prepared for the purpose of educating the public health workforce in relevant aspects of bioterrorism preparedness and response. Instructors are encouraged to freely use portions or all of the material for its intended purpose. Project Coordinator Patrick O’Carroll, MD, MPH Northwest Center for Public Health Practice, University of Washington, Seattle, WA Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Atlanta, GA Lead Developer Jennifer Brennan Braden, MD, MPH Northwest Center for Public Health Practice, University of Washington, Seattle, WA Design and Editing Judith Yarrow Health Policy Analysis Program, University of Washington, Seattle, WA The following people provided technical assistance or review of the materials: Jeffrey S. Duchin, MD: Communicable Disease Control, Epidemiology and Immunization Section, Public Health – Seattle & King County -

Download Global Catastrophic Risks 2020

Global Catastrophic Risks 2020 Global Catastrophic Risks 2020 INTRODUCTION GLOBAL CHALLENGES FOUNDATION (GCF) ANNUAL REPORT: GCF & THOUGHT LEADERS SHARING WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW ON GLOBAL CATASTROPHIC RISKS 2020 The views expressed in this report are those of the authors. Their statements are not necessarily endorsed by the affiliated organisations or the Global Challenges Foundation. ANNUAL REPORT TEAM Ulrika Westin, editor-in-chief Waldemar Ingdahl, researcher Victoria Wariaro, coordinator Weber Shandwick, creative director and graphic design. CONTRIBUTORS Kennette Benedict Senior Advisor, Bulletin of Atomic Scientists Angela Kane Senior Fellow, Vienna Centre for Disarmament and Non-Proliferation; visiting Professor, Sciences Po Paris; former High Representative for Disarmament Affairs at the United Nations Joana Castro Pereira Postdoctoral Researcher at Portuguese Institute of International Relations, NOVA University of Lisbon Philip Osano Research Fellow, Natural Resources and Ecosystems, Stockholm Environment Institute David Heymann Head and Senior Fellow, Centre on Global Health Security, Chatham House, Professor of Infectious Disease Epidemiology, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine Romana Kofler, United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs Lindley Johnson, NASA Planetary Defense Officer and Program Executive of the Planetary Defense Coordination Office Gerhard Drolshagen, University of Oldenburg and the European Space Agency Stephen Sparks Professor, School of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol Ariel Conn Founder and -

Applying Traditional Jurisdictional Frameworks to a Modern Threat

PROSECUTING CYBERTERRORISTS: APPLYING TRADITIONAL JURISDICTIONAL FRAMEWORKS TO A MODERN THREAT Paul N. Stockton* & Michele Golabek-Goldman** The United States faces a growing risk of cyberterrorism against its finan- cial system, electric power grid, and other critical infrastructure sectors. Senior U.S. policymakers note that building U.S. capacity to prosecute cyberterrorists could play a key role in deterring and disrupting such attacks. To facilitate pros- ecution, the federal government is bolstering its technical expertise to attribute attacks to those who perpetrate them, even when, as is increasingly the case, the perpetrators exploit computers in dozens of nations to strike U.S. infrastructure. Relatively little attention has been paid, however, to another prerequisite for prosecuting cyberterrorists: that of building a legal framework that can bring those who attack from abroad to justice. The best approach to prosecuting cyberterrorists striking from abroad is to add extraterritorial application to current domestic criminal laws bearing on cyberattack. Yet, scholars have barely begun to explore how the United States can best justify such extraterritorial extension under international law and assert a legitimate claim of prescriptive jurisdiction when a terrorist hijacks thousands of computers across the globe. Still less attention has been paid to the question of how to resolve the conflicting claims of national jurisdiction that such attacks would likely engender. This Article argues that the protective principle—which predicates prescrip- tive jurisdiction on whether a nation suffered a fundamental security threat— should govern cyberterrorist prosecutions. To support this argument, the Article examines the full range of principles on which States could claim prescriptive ju- risdiction and assesses their strengths and weaknesses for extending extraterrito- rial application of U.S. -

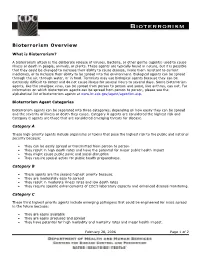

Bioterrorism

BIOTERRORISM Bioterrorism Overview What is Bioterrorism? A bioterrorism attack is the deliberate release of viruses, bacteria, or other germs (agents) used to cause illness or death in people, animals, or plants. These agents are typically found in nature, but it is possible that they could be changed to increase their ability to cause disease, make them resistant to current medicines, or to increase their ability to be spread into the environment. Biological agents can be spread through the air, through water, or in food. Terrorists may use biological agents because they can be extremely difficult to detect and do not cause illness for several hours to several days. Some bioterrorism agents, like the smallpox virus, can be spread from person to person and some, like anthrax, can not. For information on which bioterrorism agents can be spread from person to person, please see the alphabetical list of bioterrorism agents at www.bt.cdc.gov/agent/agentlist.asp. Bioterrorism Agent Categories Bioterrorism agents can be separated into three categories, depending on how easily they can be spread and the severity of illness or death they cause. Category A agents are considered the highest risk and Category C agents are those that are considered emerging threats for disease. Category A These highpriority agents include organisms or toxins that pose the highest risk to the public and national security because: • They can be easily spread or transmitted from person to person • They result in high death rates and have the potential for major public health impact • They might cause public panic and social disruption • They require special action for public health preparedness. -

Global Catastrophic Risks 2017 INTRODUCTION

Global Catastrophic Risks 2017 INTRODUCTION GLOBAL CHALLENGES ANNUAL REPORT: GCF & THOUGHT LEADERS SHARING WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW ON GLOBAL CATASTROPHIC RISKS 2017 The views expressed in this report are those of the authors. Their statements are not necessarily endorsed by the affiliated organisations or the Global Challenges Foundation. ANNUAL REPORT TEAM Carin Ism, project leader Elinor Hägg, creative director Julien Leyre, editor in chief Kristina Thyrsson, graphic designer Ben Rhee, lead researcher Erik Johansson, graphic designer Waldemar Ingdahl, researcher Jesper Wallerborg, illustrator Elizabeth Ng, copywriter Dan Hoopert, illustrator CONTRIBUTORS Nobuyasu Abe Maria Ivanova Janos Pasztor Japanese Ambassador and Commissioner, Associate Professor of Global Governance Senior Fellow and Executive Director, C2G2 Japan Atomic Energy Commission; former UN and Director, Center for Governance and Initiative on Geoengineering, Carnegie Council Under-Secretary General for Disarmament Sustainability, University of Massachusetts Affairs Boston; Global Challenges Foundation Anders Sandberg Ambassador Senior Research Fellow, Future of Humanity Anthony Aguirre Institute Co-founder, Future of Life Institute Angela Kane Senior Fellow, Vienna Centre for Disarmament Tim Spahr Mats Andersson and Non-Proliferation; visiting Professor, CEO of NEO Sciences, LLC, former Director Vice chairman, Global Challenges Foundation Sciences Po Paris; former High Representative of the Minor Planetary Center, Harvard- for Disarmament Affairs at the United Nations Smithsonian