The Opinion Podcast: a Visceral Form of Persuasion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Looking for Podcast Suggestions? We’Ve Got You Covered

Looking for podcast suggestions? We’ve got you covered. We asked Loomis faculty members to share their podcast playlists with us, and they offered a variety of suggestions as wide-ranging as their areas of personal interest and professional expertise. Here’s a collection of 85 of these free, downloadable audio shows for you to try, listed alphabetically with their “recommenders” listed below each entry: 30 for 30 You may be familiar with ESPN’s 30 for 30 series of award-winning sports documentaries on television. The podcasts of the same name are audio documentaries on similarly compelling subjects. Recent podcasts have looked at the man behind the Bikram Yoga fitness craze, racial activism by professional athletes, the origins of the hugely profitable Ultimate Fighting Championship, and the lasting legacy of the John Madden Football video game. Recommended by Elliott: “I love how it involves the culture of sports. You get an inner look on a sports story or event that you never really knew about. Brings real life and sports together in a fantastic way.” 99% Invisible From the podcast website: “Ever wonder how inflatable men came to be regular fixtures at used car lots? Curious about the origin of the fortune cookie? Want to know why Sigmund Freud opted for a couch over an armchair? 99% Invisible is about all the thought that goes into the things we don’t think about — the unnoticed architecture and design that shape our world.” Recommended by Scott ABCA Calls from the Clubhouse Interviews with coaches in the American Baseball Coaches Association Recommended by Donnie, who is head coach of varsity baseball and says the podcast covers “all aspects of baseball, culture, techniques, practices, strategy, etc. -

Television Academy Awards

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Directing For A Documentary/Nonfiction Program Adam Ruins Everything Adam Ruins Guns November 27, 2018 Adam Conover takes aim at both sides of the gun debate by explaining why an assault weapons ban would be ineffective at stopping gun violence, outlining how the Second Amendment has been twisted to benefit the NRA, and revealing that liberal and conservative gun policies have impacted people of color. Tim Wilkime, Directed by America To Me Listen To The Poem! September 30, 2018 Spring semester brings fresh challenges. Jada clashes with junior Diane over her new film. Brendan recalls a racially charged basketball past. Tiara and the cheerleading squad go for the gold. Charles’ poetry slam team faces an epic challenge. Steve James, Directed by American Dream/American Knightmare December 21, 2018 Documentary that delves into the life and exploits of the iconic Death Row Records co-founder Suge Knight, and the era in gangsta rap he presided over. Through a series of face-to-face interviewers, Knight reveals exactly how it all happened and why it all fell apart. Antoine Fuqua, Directed by American Experience: The Circus October 08, 2018 - October 09, 2018 American Experience: The Circus explores the colorful history of this popular, influential and distinctly American form of entertainment, from the first one-ring show at the end of the 18th century to 1956, when the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey big top was pulled down for the last time. Sharon Grimberg, Directed by American Experience: The Eugenics Crusade October 16, 2018 American Experience: The Eugenics Crusade explores the unknown campaign to breed a “better” American race. -

Digital News Report 2018 Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism / Digital News Report 2018 2 2 / 3

1 Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2018 Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism / Digital News Report 2018 2 2 / 3 Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2018 Nic Newman with Richard Fletcher, Antonis Kalogeropoulos, David A. L. Levy and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen Supported by Surveyed by © Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism / Digital News Report 2018 4 Contents Foreword by David A. L. Levy 5 3.12 Hungary 84 Methodology 6 3.13 Ireland 86 Authorship and Research Acknowledgements 7 3.14 Italy 88 3.15 Netherlands 90 SECTION 1 3.16 Norway 92 Executive Summary and Key Findings by Nic Newman 8 3.17 Poland 94 3.18 Portugal 96 SECTION 2 3.19 Romania 98 Further Analysis and International Comparison 32 3.20 Slovakia 100 2.1 The Impact of Greater News Literacy 34 3.21 Spain 102 2.2 Misinformation and Disinformation Unpacked 38 3.22 Sweden 104 2.3 Which Brands do we Trust and Why? 42 3.23 Switzerland 106 2.4 Who Uses Alternative and Partisan News Brands? 45 3.24 Turkey 108 2.5 Donations & Crowdfunding: an Emerging Opportunity? 49 Americas 2.6 The Rise of Messaging Apps for News 52 3.25 United States 112 2.7 Podcasts and New Audio Strategies 55 3.26 Argentina 114 3.27 Brazil 116 SECTION 3 3.28 Canada 118 Analysis by Country 58 3.29 Chile 120 Europe 3.30 Mexico 122 3.01 United Kingdom 62 Asia Pacific 3.02 Austria 64 3.31 Australia 126 3.03 Belgium 66 3.32 Hong Kong 128 3.04 Bulgaria 68 3.33 Japan 130 3.05 Croatia 70 3.34 Malaysia 132 3.06 Czech Republic 72 3.35 Singapore 134 3.07 Denmark 74 3.36 South Korea 136 3.08 Finland 76 3.37 Taiwan 138 3.09 France 78 3.10 Germany 80 SECTION 4 3.11 Greece 82 Postscript and Further Reading 140 4 / 5 Foreword Dr David A. -

Strategic Management Can New Players Still Compete with the Giants?

Master Thesis Business Administration – Strategic Management Can new players still compete with the giants? Analyzing the creation of new platforms and how their strategies change overtime in the music platform industry Author: Maikel Coeleman Student number: S4357736 Supervisor: Dr. S. Khanagha Second examiner: Dr. G.W. Ziggers Date: 25-8-2018 1 Table of contents 1. Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Problem Statement ....................................................................................................................... 5 1.2 Relevance ...................................................................................................................................... 8 1.3 Outline Thesis ................................................................................................................................ 9 2. Theoretical background ..................................................................................................................... 10 2.1 How to deal with the dilemmas of platform creation ................................................................. 10 2.2 Roger’s diffusion of innovations .................................................................................................. 10 2.3 First-, second- & late-movers ...................................................................................................... 17 3. Methodology .................................................................................................................................... -

Mediated Political Participation: Comparative Analysis of Right Wing and Left Wing Alternative Media

Mediated Political Participation: Comparative Analysis of Right Wing and Left Wing Alternative Media A dissertation presented to the faculty of the Scripps College of Communication of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Nune Grigoryan August 2019 © 2019 Nune Grigoryan. All Rights Reserved. This dissertation titled Mediated Political Participation: Comparative Analysis of Right Wing and Left Wing Alternative Media by NUNE GRIGORYAN has been approved for the School of Media Arts & Studies and the Scripps College of Communication by Wolfgang Suetzl Assistant Professor of Media Arts & Studies Scott Titsworth Dean, Scripps College of Communication ii Abstract GRIGORYAN, NUNE, PhD, August 2019, Mass Communication Mediated Political Participation: Comparative Analysis of Right Wing and Left Wing Alternative Media Director of dissertation: Wolfgang Suetzl Democracy allows a plural media landscape where different types of media perform vital functions. Over years, the public trust towards mainstream media has been eroding, limiting their ability to fulfill democratic functions within the American society. Meanwhile, the Internet has led to proliferation of alternative media outlets on digital space. These platforms allow new outreach and mobilizing opportunities to the once peripheral alternative media. So far, the literature about alternative media have been heavily focused on left-wing alternative media outlets, while the research on alternative right-wing media has remained scarce and fragmented. Only few studies have applied a comparative analysis approach to study these outlets. Moreover, research that examines different aspects of alternative media such as content and audience reception is more rare. This study aims to demonstrate the heterogeneity of alternative media by highlighting their history and functions within the American democracy. -

What's Podcasting to You? Exploring Perspectives of Consumers and Producers

What's Podcasting to you? Exploring Perspectives of Consumers and Producers Student Name - Arshdeep Chawla Module - COMM5600: Dissertation & Research Methods Course - MA New Media Submitted on - 3 September 2018 Page !1 of !79 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 4 Chapter I - Literature Review 6 Podcasting 6 Overview: Podcasting Industry 7 Overview: Podcast Production 11 Experimental Application Perpective 16 Emerging Technologies - Redefining Podcast Discovery? 17 Pivotal Shows and Trends 21 Chapter II - Methodology 23 Interview 24 Chapter III - Findings, Discussions and Analysis 29 Podcasting 29 Software 33 Smart Speakers 34 Production, Distribution and Technology 36 Closing Remarks 41 Chapter IV - Conclusion 42 List of References 45 Appendices 54 Appendix I - Transcripts 54 Appendix II - Ethics Form 76 Appendix III - Research Checklist 77 Appendix IV - Information Sheet 78 Page !2 of !79 Abstract Past research has widely investigated podcasting in academia and education. Some research has investigated motivations of podcasters and listeners using quantitive methods. However, little is known about perspectives of podcast users and producers with respect to technological and cultural changes in the medium. This dissertation outlines findings from interviews conducted with podcast users and a podcast producer that lays out thoughts about the medium on themes like technology, production, distribution etc. Page !3 of !79 Introduction Podcasting, an automated subscription-based system of recorded audio/video content powered by the internet, finds its origins in the early 2000s and witnessed wide adoption in 2005. This makes podcasting older than Facebook or Twitter, two very popular products of the internet age. Although, podcasting has not been able to replicate the same success as those social networking sites, it has had a few pivotal moments that left an indelible impact on the digital media industry. -

University of Oklahoma Graduate College

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE PODCAST RHETORICS INSIGHTS INTO PODCASTS AS PUBLIC PERSUASION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By MATTHEW VINCENT JACOBSON Norman, Oklahoma 2021 PODCAST RHETORICS INSIGHTS INTO PODCASTS AS PUBLIC PERSUASION A DISSERTATION APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH BY THE COMMITTEE CONSISTING OF Dr. William Kurlinkus, Chair Dr. Bill Endres Dr. Justin Reedy Dr. Roxanne Mountford Dr. Sandra Tarabochia © Copyright by MATTHEW VINCENT JACOBSON 2021 All Rights Reserved. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements . viii Abstract . xii Chapter 1: The Argument for Rhetorically Analyzing Podcasts . 1 I. Introduction . 2 II. Rhetorically Defining Podcasts . 5 III. A Call for Podcast Scholarship . 14 IV. Podcast Scholarship in Rhetoric and Writing Studies . 18 V. The Need to Rhetorically Analyze Podcast Rhetoric . 24 VI. Introducing Three Analytics of Podcasting: Technology, Sonic, and Conversational Rhetorics in a Public Argument Over Mask Wearing in The Joe Rogan Experience . 28 VII. Project Overview . 44 Chapter 2: The Technological Horizons of Podcast Persuasion . 45 Chapter 3: The Sounds of Podcast Rhetoric . 47 Chapter 4: Deliberation or Demagoguery? The Rhetoric of Podcast Conversations . 50 Chapter 2: The Technological Horizons of Podcast Persuasion . 53 I. Introduction . 54 II. Rhetorical Theories of Philosophy of Technology . 55 III. The Technological Rhetoric of Podcast Technologies . 64 A. The Rhetoric of Podcasting’s Regulatory Context in the U.S. and the Standing Reserve of Internet Audiences . .64 B. The Rhetoric of Production and Post-Production Tech . .72 v C. The Rhetoric of Distribution and “Listening” Tech . 98 D. -

New York City, the Podcasting Capital

NEW YORK CITY, THE PODCASTING CAPITAL TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 7 INTRODUCTION 9 A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE PODCAST 11 NATIONAL LANDSCAPE OF PODCASTING 12 PODCAST GROWTH 14 ADVERTISING 15 THE IMPACT OF PODCAST ADVERTISING 16 ADVERTISING MODELS IN PODCASTING 17 PRICING MODEL 18 ADVERTISING TECHNOLOGY 19 NEW YORK CITY, THE CAPITAL OF PODCASTING 20 NEW YORK CITY’S PODCAST NETWORKS 22 NEW YORK CITY PODCAST INDUSTRY GROWTH 23 THE NEW YORK CITY PODCAST COMMUNITY 24 INCREASING DIVERSITY IN NEW YORK CITY PODCASTING 26 TECHNOLOGY 28 THE FUTURE OF PODCASTING 30 CONCLUSION 31 PODCASTERS’ FAVORITE PODCASTS 32 REFERENCES 33 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Podcasts are the newest form of the oldest entertainment medium: storytelling. Today’s podcasts are a major forum for the exchange of ideas, and many are calling this time the “renaissance of podcasting.” Born out of the marriage of public radio and the internet, podcasting has adapted to follow modern consumption patterns and the high demand for readily accessible entertainment. Podcasts are making New York City their home. The density of advertising firms, technology companies, major brands, digital media organizations, and talent has established New York City as the epicenter of the burgeoning podcast industry. New York City is home to the fastest growing podcast startups, which have doubled, tripled, and quadrupled their size in the past several years – in employment, office space, and listenership. New York City’s podcast networks are growing rapidly, reflecting the huge national audience of 42 million weekly listeners. Employment at the top New York City podcast networks has increased over the past several years, from about 450 people in 2015 to about 600 people in early 2017. -

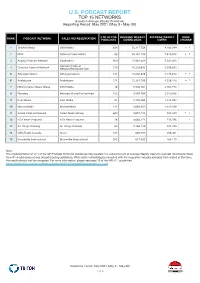

U.S. PODCAST REPORT TOP 15 NETWORKS Based on Average Weekly Downloads Reporting Period: May 2021 (May 3 - May 30)

U.S. PODCAST REPORT TOP 15 NETWORKS Based on Average Weekly Downloads Reporting Period: May 2021 (May 3 - May 30) # OF ACTIVE AVERAGE WEEKLY AVERAGE WEEKLY RANK RANK PODCAST NETWORK SALES REPRESENTATION PODCASTS DOWNLOADS USERS CHANGE 1 Stitcher Media SXM Media 459 35,317,758 9,163,399 1 2 NPR National Public Media 55 35,162,199 7,425,526 1 3 Audacy Podcast Network Cadence13 500 17,982,442 5,542,005 Cumulus Podcast 4 Cumulus Podcast Network Network/Westwood One 270 15,225,592 3,556,832 5 AdLarge/cabana AdLarge/cabana 134 13,050,876 4,173,613 1 6 Audioboom Audioboom 274 12,281,759 4,326,418 1 7 NBCUniversal News Group SXM Media 46 9,926,761 2,764,770 8 Wondery Wondery Brand Partnerships 102 9,589,764 2,910,636 9 Kast Media Kast Media 93 3,795,469 1,514,087 10 WarnerMedia WarnerMedia 114 3,698,251 1,437,168 11 Salem Podcast Network Salem Media Group 662 2,691,743 534,539 1 12 FOX News Podcasts FOX News Podcasts 48 2,665,171 735,796 1 13 All Things Comedy All Things Comedy 52 2,166,142 944,325 14 CBC/Radio-Canada Acast 333 685,707 236,461 15 Bonneville International Bonneville International 252 647,352 184,170 Note: The implementation of v2.1 of the IAB Podcast Technical Guidelines has resulted in a reduced count of Average Weekly Users for podcast downloads made from IP v6 addresses across all participating publishers. While both methodologies complied with the respective industry standard that existed at that time, the results should not be compared. -

DG Diss DRAFT 3

UCSF UC San Francisco Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Homo experimentus: digital selves and digital health in the age of innovation Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8h92q6rt Author Greenfield, Dana Emily Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California ! Copyright 2015 by Dana Emily Greenfield ! ii! ! To the memory of my mother Linda Brodsky, MD, who dedicated herself to continuous improvement and innovation, before it was fashionable. Acknowledgments I owe many thanks to the UCSF Department of Anthropology, History and Social Medicine (DAHSM) and the UC Berkeley Department of Anthropology. In particular, this work would not be possible without the guidance and insights of my committee: Vincanne Adams, Ian Whitmarsh, Cori Hayden and David Winickoff. As my dissertation chair, Vincanne provided hours of close reading and thoughtful dialogue to help shape the ideas and analysis that follow. Without her keen editorial vision, this work would be much less coherent. Ian Whitmarsh also provided so much expansive thought to this work and the years of graduate training that undergirds it. He always reminds us to “write at our edge,” where understanding begins to unfold. I thank Cori Hayden for her imagination and diagnostic acuity. From her, I have learned to find new openings and new ways to see the world ethnographically. Finally, David provides his incisive and discerning input, and serves as a model for living at the boundaries between theory and practice. Dawn Nafus provided critical readings of Chapter 2, and the opportunity to publish an earlier version of this material in a forthcoming edited volume. -

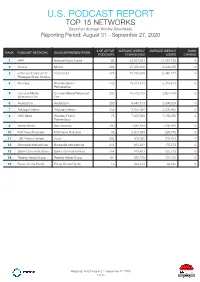

U.S. PODCAST REPORT TOP 15 NETWORKS Based on Average Weekly Downloads Reporting Period: August 31 - September 27, 2020

U.S. PODCAST REPORT TOP 15 NETWORKS Based on Average Weekly Downloads Reporting Period: August 31 - September 27, 2020 # OF ACTIVE AVERAGE WEEKLY AVERAGE WEEKLY RANK RANK PODCAST NETWORK SALES REPRESENTATION PODCASTS DOWNLOADS USERS CHANGE 1 NPR National Public Media 56 43,572,051 12,462,136 0 2 Stitcher Midroll 298 27,070,805 8,209,075 0 3 Entercom/Cadence13/ Cadence13 375 22,235,386 6,340,271 0 Pineapple Street Studios 4 Wondery Wondery Brand 132 19,781,418 5,314,101 0 Partnerships 5 Cumulus Media/ Cumulus Media/Westwood 293 16,316,706 3,561,410 0 Westwood One One 6 Audioboom Audioboom 255 9,446,513 3,099,324 0 7 AdLarge/cabana AdLarge/cabana 152 8,855,824 3,206,085 0 8 NBC News Wondery Brand 25 7,908,999 2,159,353 0 Partnerships 9 WarnerMedia WarnerMedia 100 4,040,941 1,398,936 0 10 FOX News Podcasts FOX News Podcasts 45 2,801,999 825,756 0 11 CBC/Radio-Canada Acast 202 908,828 308,438 0 12 Bonneville International Bonneville International 243 681,304 175,873 0 13 Salem Communications Salem Communications 564 619,461 125,713 0 14 Beasley Media Group Beasley Media Group 154 552,276 132,408 0 15 Focus On the Family Focus On the Family 16 425,414 94,182 0 Reporting Period: August 31 - September 27, 2020 1 of 11 U.S. PODCAST REPORT TOP 100 PODCASTS BY DOWNLOADS Podcasts Ranked by Average Weekly Downloads in the United States Reporting Period: August 31 - September 27, 2020 # OF NEW RANK RANK PODCAST PODCAST NETWORK SALES REPRESENTATION EPISODES CHANGE 1 NPR News Now NPR National Public Media 672 0 2 The Ben Shapiro Show Cumulus Media/Westwood -

Examining Twenty-First Century Ecofeminist Digital

THESIS “CUT HER SOME SLACK.”: EXAMINING TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY ECOFEMINIST DIGITAL OPINION LEADER #AOC AND THE #GREENNEWDEAL Submitted by Zoe Eileen Clemmons Department of Journalism and Media Communication In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the Degree of Master of Science Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado Summer 2020 Master’s Committee: Advisor: Tori Omega Arthur Karrin Anderson Joseph Champ Copyright by Zoe Eileen Clemmons 2020 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT “CUT HER SOME SLACK.”: EXAMINING TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY ECOFEMINIST DIGITAL OPINION LEADER #AOC AND THE #GREENNEWDEAL Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez holds a unique and captivating spot in the political arena in 2020. At the forefront of the nonbinding resolution, the Green New Deal (GND), her position on Twitter with over 6.7 million followers has given her the power to influence and interact with her constituents, other politicians, supporters, and critics on Twitter and has given her the opportunity to advocate for and uphold key policy issues related to environmental justice within the Green New Deal. She can also shape policy decisions as the Green New Deal moves forward. Ecofeminism, as both a social and philosophical movement, argues that women must be at the forefront of politics in order to improve the lives of others and the environment. Employing Critical Technocultural Discourse Analysis (CTDA) to understand digital phenomena, artifacts, and ideology on social networking platforms, this study explores how and why Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez as a twenty-first century opinion-leader generates support for the Green New Deal, and how she uses ecofeminism as a principle that guides her Green New Deal advocacy on Twitter.